Canada's Rock Royalty

From Boyhood Basement Band To The Top

By Joe Milliken, Goldmine, June 13, 2003, transcribed by pwrwindows

Over 29 years, 40 million in sales of 24 albums and countless performances, Canadian trio Rush have established themselves as the premier progressive hard-rock band in the world. This is the story of a Toronto bar band who turned into international stars without ever compromising their musical beliefs.

The journey began in the Toronto suburb of Willowdale when young Alex Lifeson (real last name Zivejinovich) received his first guitar for Christmas at the age of 12. He had already been exposed to music through the viola in school and a friend's borrowed guitar. Lifeson then joined with John Rutsey, a friend who lived across the street, after hearing him banging away on a second-hand drum kit. The two started practicing in each other's basements.

The young guitarist and drummer decided to form a band, calling themselves The Projections. They needed a bass player and friend Jeff Jones was recruited. Lifeson, Rutsey, and Jones spent the summer of 1968 learning the radio hits of the day.

They worked out a few Cream songs and booked their first gig at a coffee house - in a church basement - called The Coffin. A few days prior to the gig, Rutsey's brother came up with the name Rush, and the band was born.

The first show was good enough to get them another gig there, however Jones canceled at the last minute. Enter Gary Lee, a local bass player whom Lifeson had jammed with a few times.

"Often I would call Geddy up to borrow his amp, but this time I asked, 'Do you think you could come play with us? We have a gig tonight and don't have a bass player,'" Lifeson told Bill Banasiewicz, a writer and the foremost Rush historian. Lee, a Polish Jew whose family moved to Canada after World War II, acquired the name "Geddy" because of his grandmother saying Gary in a heavy Yiddish accent. "Geddy" has followed him ever since.

Rush's first performance with Lee drew 30 people, and the band earned $25. "Our first show. (with Geddy( in 1968 I believe, one of the mics was a floor lamp," Lifeson said in a 2002 Canadian TV interview. "We had one of those big ol' round chrome microphones taped to a lamp because we had no mic stand - and one amp! We were born plugged into the same amplifier."

Lee added, "We got enough money so we could go to the deli afterwards for chips and gravy - and that was like, awesome! We did a gig and got paid. We were professional musicians." After the show Lee was elected a permanent member.

"We came from pretty much the same neighborhood," Lee once told a Toronto newspaper. "We met in 8th grade .... worked in my mom's hardware store for a while, Alex worked in a gas station. When I first started doing this my mom was against it," Lee told Circus Magazine in 1976.

"She had come out of the war - a concentration camp - and wanted me to be what her people could never be: to grow up and have the security of being a doctor or whatever. 'My son should never go without shoes or food,' is what she thought. Until of course, she saw me on TV - she could relate to TV Then it was, 'My son is on TV!'"

At a very young age we decided we wanted to be musicians," Lee said in a Canadian TV interview. "And from that point on we didn't have to wonder. You didn't know if you were going to be successful or fail, but you knew you were going to be a musician and that's what you had to do." In December 1968, Rush added keyboard player Lindy Young. Lifeson was friends with Young's sister and had also been borrowing his Gibson guitar. The new four-piece lineup continued to rehearse in a blues-rock style, debuting at The Coff-In in January 1969.

"Lindy was a real good musician. He could also play drums, guitar, harmonica and sing," Lifeson told Banasiewicz. "He helped us evolve musical1y, and we started to get into some different things like early Grateful Dead."

Young would eventually leave the band to pursue a college degree. With the debut release of British heavy-metal blues band Led Zeppelin, Rush found the direction to take. They somehow got more amps, and Lee started singing in that high-pitched Robert Plant-like falsetto that would one day also make him famous.

Lee, Lifeson, and Rutsey were noticed by a manager/booking agent named Ray Daniels. He began booking shows for them, at times a tall order because the band was now starting to play more original material. Kids at high-school dances wanted danceable radio hits.

A breakthrough came with the reduction of the legal drinking age from 21 to 18, opening up many venues to Rush. Their first bar gig was in the Toronto club Gasworks, and the show came off pretty well considering they were petrified. However, Daniels continued to have a tough time booking gigs for them.

"Club owners didn't want to hear it. Their big concern was that the waitresses couldn't hear the beer orders," Lee told Creem Magazine.

Over the next year and a half the band honed their live act. Suddenly Rush were pulling in $1,000 a week. Progressive sounds of the times - such as Yes, Genesis, and Emerson, Lake And Palmer - found their way into their music. Lifeson began taking classical guitar lessons, and, along with Lee's increased interest in art rock, they started developing their signature sound.

Eventually, Lifeson , Rutsey, and Lee had enough funds to enter Eastern Sound Studios in Toronto with producer David Stock to record a single to shop around to labels. Rush put down the only cover song they would ever record, the Buddy Holly classic "Not Fade Away,'" backed with a rocker called "You Can't Fight It."

Daniels brought the Single to several labels, but no one offered a recording contract. However, London Records did offer to distribute the Single if Daniels formed his own label. Called Moon Records, Rush could now finally release their first single. Unfortunately, it went nowhere.

The sudden break in momentum stirred up doubt for Rutsey. "I was going through a real struggle with the band at this point," he told Banasiewicz. "I was a mixed-up kid and felt like quitting."

The challenge of recording a full -length album was also upon the band. The band could only afford the cheapest recording time slots available - studio downtime in the middle of the night. Daniels called upon his friend, Terry Brown, a well-known producer and owner of Toronto Sound Studios, who helped complete the project for just under $10,000.

Daniels brought the new tapes around to different record companies but again, no one was interested. So he again approached London Records. Daniels and Wilson again put up their own money and had 3,500 copies of the record pressed. It was released under the Moon label, simply titled Rush. Prior to its release, Rush went on a brief tour with, interestingly enough, Mahogany Rush and Bullrush. The tour also included a stint opening up for glam-rockers New York Dolls, which brought the band in front of crowds of more than 1,000 for the first time. Rush was finally released in January 1974.

"I can remember getting that first copy, and playing it and thinking, 'Wow, I played on this!,'" Lifeson said in a 1990 Canadian TV interview. "Back in the early '70s we were young?just a bar band. At that time, to have a record come out was a really big deal."

Rush's first show in the U.S. was at a spring 1974 pop festival in East Lansing, Mich. The show did not go over very well, however, due to inclement weather and a crowd unfamiliar with the band's material. They finally got a break when Donna Harper, a program director at Cleveland's WMMS-FM and a friend of Daniels, heard Rush. "The first time I played 'Working Man' I knew it would be a hit in working class Cleveland, n Harper told Banasiewicz. She had a OJ put the track in the station's regular rotation, and listeners began calling to ask where the new Led Zeppelin song had come from. The next day Daniels sent a shipment of Rush albums to a record store in Cleveland. They were gone within a few days.

From there the band landed a gig opening for ZZ Top in a 3,000-seat theater. They were a little nervous playing before their largest crowd yet, but there were actually some Rush fans in the audience yelling out Rush song titles and singing along. The debut album had now sold 5,000 copies. The successful show and Cleveland airplay stirred some interest among a few U.S. record companies. Rush also began using a booking agent, Ian Blacker of American Talent International, who would eventually become the band's co-manager. He sent a copy of Rush to Mercury Records. The band's contract was agreed upon over the phone: They would receive a $50,000 advance, plus $25,000 toward future recording costs. A five-month North American tour would begin in August, with the debut album out three weeks prior to the start of the tour.

With all the newfound attention and pressure, Rutsey's unhappiness at being in a rock band had been overlooked. He dreaded months of touring as a second-billed act, and his diabetes just became too much for him to deal with, so he left the band.

With the start of the tour just two weeks away, an audition was set up for Neil Peart, from a St. Catherine's, Ontario, bar band called Hush. Peart had started out on piano but had shifted to drums at an early age. At 18, he had traveled to England in search of his musical dreams and aspirations.

"When you go out into the big world," he once told Modern Drummer Magazine, "you're in for a lot of disillusionment. So while I was there I did a lot of other things besides music to put bread in my mouth. When I came back I had a different perspective about the musicˇ business. I decided that I would be a semi-professional musician for my own entertainment and wouldn't count on it to make my living."

Peart showed up for his audition in a beat-up old car and his drum kit packed in garbage cans. Lifeson and Lee had reservations - until he started playing in an intense Keith Moon-like style. They sat around and talked for a while, and after discovering that they liked a lot of the same kinds of music and books, Peart was in, officially joining Rush on Lee's 21st birthday-July 29, 1974.

They rehearsed until the start of the tour, which began in August in Pittsburg, on a bill that included Uriah Heep and Manfred Mann's Earth Band. Peart's first appearance with Rush, amazingly enough, was in front of 10,000 people. The band got through the half-hour set, which included a drum solo that remains a Rush concert staple to this day.

Being the opening act left a great deal of time for Rush to write new material , much or which would end up on the second album. During the tour Rush would open up shows for a literal "who's who" of classic rock including Kiss, Nazareth, Blue Oyster Cult, and Rory Gallagher. They recorded a Toronto show for King Biscuit Flower Hour, appeared on the music television series Don Kirschner's Rock Concert and also recorded another concert radio show from New York's famed Electric Ladyland Studios.

The exposure gave the band momentum as they returned to the studio to record their second album. Peart had taken over the task of writing most of the lyrics, leaving Lifeson and Lee to work out song structures and melodies.

"I basically took it over because no one else wanted to do it," Peart said. "I've always been interested in words and always loved to read, so I thought why not give it a try. 1 wrote a couple of songs and showed them to Alex and Geddy [the first being 'Fly By Night'], and they liked them, so I continued. It later would become an obsession."

Brown produced their second album, titled Fly By Night, which was recorded in a mere 10 days. The same day the mixing was complete the band flew to Winnipeg for an evening show. The first Rush album featuring Peart on drums shows a vast improvement in the band's sound, and their tempo changing style developing. It also marks the beginning of Rush's epic concept pieces of the 1970s, with the dramatic "By-Tor & The Snow Dog Medley [sic]" and "Rivendell," which was derived from J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord Of The Rings.

Fly By Night was released in February 1975, and Rush went back on the road , opening for American rock legends Aerosmith and Kiss. Other highlights during this time included Lifeson marrying his childhood sweetheart Charlene and the band receiving a Juno Award - the Canadian equivalent of America's Grammy Award - for Most Promising New Group.

Rush closed out the 1975 tour in grand fashion by headlining and selling out Canada's famed Massey Hall in Toronto. The band and Brown returned to Toronto Sound Studio in the summer of 1975 to begin recording Caress Of Steel. From the hard-rockin' opener "Bastille Day" to the tongue in -cheek humor of "I Think I'm Going Bald" to the creative instrumentation in "Didacts And Narpets," Rush had taken great strides from their debut album. One entire side of the album revolves around a single story line, here titled "Fountain Of Lamneth."

The adventurous concept of several parts tells of a man on an epic journey. The album also continues the "By-Tor" story from the previous album with "The Necromancer," a three part tale of a battle between By-Tor and his nemesis.

Caress Of Steel further stretched the band. Although it was probably too advanced for most listeners to fully grasp, some die-hard Rush fans feel that it is the most well-rounded work Rush have ever done.

Released in September 1975, Caress Of Steel received a lukewarm response. Album and ticket sales slumped. Mercury suggested a return to the Led Zeppelin-esque rock style of the first album. Instead, Rush decided to rise or fall on their own terms and put together an album about striving for creative freedom.

The album's story concerns a futuristic war between galaxies in which all worlds become ruled by computer-wielding priests. However, one man within this inner-planetary struggle discovers a guitar and teaches himself music, only to be rejected by his leaders. The musician falls asleep and dreams of a creative paradise. only to awaken again, disappointed. He then takes his own life in hopes of fin ding that creative paradise. This idea was forged from a fascination provided by author Ayn Rand, whom Peart greatly admired.

Peart would later say, "It was uncertain whether we would fight or fall, but finally we just got mad and came back with a vengeance. We were talking about creative freedom , and we meant it!"

Unlike the hurried sessions of the previous album, Rush and Brown (now nicknamed "Broon" by the band) entered Toronto Sound Studio with a month set aside to record 2112, making certain the material didn't become more complex than they could re-create on stage. During the recording of 2112, the band explored new recording technologies, including various synthesizers and digital -delay features. They even brought in an outside source for the first time, with Hugh Syme from Canada's Ian Thomas Band contributing synthesizer and Mellotron parts. (Syme had created the front cover of Caress Of Steel and was now putting together the 2112 cover as well.)

Mercury Records executives were not happy.

2112 was released as Rush prepared for the opening show of the tour in Los Angeles on March 18, 1976. It sold 100,000 copies in the first week of its release, and by the end of March it surpassed the sales of the previous three albums combined. All of a sudden Rush was headlining, selling out 5,OOO-seat arenas.

They set up a mobile recording truck to record their concert at the legendary Massey Hall in homeland Toronto. The resulting live triple album All The World's A Stage - the title taken from the Shakespearean play As You Like It! - was released in September and sold more than 250,000 copies within a few months of its release. The sales of 2112 were also still going strong, with more than 300,000 copies sold. As Rush prepared for another tour, they took a quick break so Lee could marry his longtime girlfriend Nancy Young - the sister of Lindy Young, Rush's one-time keyboardist.

Rush began the tour opening shows for Blue Oyster Cult. Ted Nugent. Aerosmith. and Robin Trower but were soon headlining. In December they were awarded Canadian gold records (50,000 units sold) for Rush and Caress Of Steel.

With the success of the live album, plus going from the opening act on a triple bill to headliner, both the band and Mercury Records grew frustrated with the lack of respect they were getting from critics. However, Rush closed out 1976 with a bang by headlining and selling out a 7,OOO-seat New Year's Eve concert at the famed Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto.

Rush continued to tour, write, learn new instruments and experiment with new equipment during soundchecks.

"We decided to try and broaden our sound on stage between the three of us by having Geddy play keyboards and bass pedals, me playing bass pedals and double-neck guitar. and Neil getting a few more percussion instruments to have some other sounds in there," Lifeson pointed out.

Now that their popularity was growing, the band wanted to eliminate the added distractions of home and traveled to Europe to record. They also booked a few weeks of shows, allowing European audiences to see Rush for the first time.

The brief tour was a sell-out, and the band entered Rockfield Studios in South Wales with most of the new material already complete and a working album title of Closer To The Heart. Upon its completion, it was renamed A Farewell To Kings. It's a stunning combination of powerful progressive rock, enchanting lyrics and warm acoustic subtleties woven together through soaring synthesizers. The album combines structured cuts such as "Closer To The Heart" and "Cinderella Man" with the futuristic "Xanadu" and "Cygnus X-I ," which tells the tale of a ship travelling through a black hole. Released in September 1977, the new album was an immediate success with fans but once again not with the media or radio.

"We're unfashionable, we're not trendy and we do things some people perceive as pretentious," Lee would later tell Rolling Stone. "But if a cri tic, for instance, pans your album, what does it really mean? If an album is good, people will find out about it on their own."

The live show was now becoming more interesting - and complicated. The band's speaker system doubled in size, with Lifeson now using stacks of Marshall cabinets. Lee played a specially designed Rickenbacker doubleneck bass, a new Mini-Moog synthesizer and had bass pedals on the floor. Peart had a black, double-bass set of Slingerland drums, complete with various chimes and percussion that literally surrounded him on stage.

Rush toured until Christmas, then took a holiday break and made another network TV appearance on Don Kirschner's Rock Concert. In February they made their second trip to Europe in which every show sold out, before returning to America. Mercury Records, wanting to take advantage of this newfound momentum, released a specially priced package of the bands' first three albums, titled Archives.

While winding down the tour in Canada, Rush received their second Juno Award, this time for Best Group Of The Year. But they couldn't rest on their laurels, 50 it was time for a new album and a return trip to Rockfield Studios with Brown. Because of the now more demanding tour schedule, there had been less time to write new material while on the road. So the trio set up shop in a nearby rehearsal house and spent a couple of weeks putting together new ideas. Rush then recorded for five straight weeks.

Hemispheres was released in the fall 1978, and, once again, the band received no radio airplay and little support from the critics. "Hemispheres is a very dark album for me to listen to ," Lee would later state. "I suppose I associate it with the whole frustration and really hard work that went into the album."

The complexity of Hemispheres was a departure from anything they had done in the past. The title track, which consumes the entire first side, offers a conclusion for the "Cygnus X-l" tale from the previous album. "La Villa Strangiato" (Weird City), a 20-minute, 12-pan suite, is an intricate piece of music based loosely around Lifeson's weird dreams, with multiple time changes and mood swings.

"We spent more time recording 'Strangiato' than the entire Fly By Night album," Lee recalled. "It's one long piece with no overdubs. It took us 40 takes to get it right."

Lee told Creem Magazine at the time, "People have this image of us. They come up to me all the time and say, 'You guys take yourselves too seriously,' and I say, 'You're full of shit.' We don't take ourselves too seriously, only what we do, because to us it's worth caring about."

Rush once again sold Out arenas across North America and also returned to Europe for six weeks. The closing pinnacle of the tour was an appearance at tile Holland Pink Pop Festival on a bill that included Dire Straits, The Rolling Stones' Mick Jagger, The Police, and Peter Tosh.

After seemingly reaching a peak in progressive, cerebral rock, Rush now wanted to have a more stripped-down rock sound. In the end, they came away with Permanent Waves (originally titled Wavelength) , a refined balance of past influences mixed with their current sound. "Natural Science" is a lyrical essay offering explanations and interpretations on the interaction between man, science and the ever-progressing mechanical world. Other direct songs include "Freewill ," "Different Strings" and "Entre Nous."

The opening track, "The Spirit Of Radio," compares a free and opened-minded radio station with a commercial one. The song also pays homage to Toronto's CFNY and its program director David Marsden, who was the first to play Rush over the airwaves in 1974. Ironically enough, this track would open the doors for Rush to finally get some FM airplay. As the band hit the road, Permanent Waves would peak at #4 on the Billboard Album chart. Within two months of its release, it went platinum in Canada and gold in America.

Upon completion of their most successful North American/U.K. lour yet and having recorded several of the shows for a future live album, the band returned home for a break.

Before starting a new project, Rush jammed with fellow Canadian rockers (and record label mates) Max Webster, who had opened several shows for the band. These gatherings turned out to be very productive, spawning a song idea called "Louis The Warrior" that would eventually turn into Rush staple "Tom Sawyer." Rush spent the next two months in Toronto's Le Studio recording what would become Moving Pictures - the first album ever mixed in digital sound.

The new album has much of the same feel as Permanent Waves, as far as shorter, more precise song structures, but Moving Pictures has a much darker feel to it, with more atmospheric keyboards. Moving Pictures would become Rush's most successful album ever, surpassing the popularity of Permanent Waves by reaching #3 on Billboard's Album chart and holding there for four weeks.

Moving Pictures displayed a wide array of musical textures and styles, from the FM rock radio structures of "Tom Sawyer," "Limelight" and "Red Barchetta" to the eery, futuristic "Witch Hunt (Part III of Fear)," "The Camera Eye" and "Vital Signs" to the progressive-metal instrumental "YYZ." By year's end Rush would notch three U.S. platinum albums - Pictures, All The World's A Stage and 2112 -and would be nominated for a Best Rock Instrumental Grammy Award.

The band picked up the touring schedule among the hugely successful Moving Pictures and sold out arenas everywhere they went. Rush now enjoyed more success than ever before. After the Moving Pictures world tour ended, they began working on two projects - a new studio album and their second live album.

The live album, Exit...Stage Left, was released in October 1981 and shows the vast improvement in musicianship from the previous live effort, including stellar performances of "Xanadu," "Passage To Bangkok," "YYZ" and "Closer To The Heart." A concert video (of the same name) was also released simultaneously. As the band began 1982, Exit...Stage Left entered the Billboard Top 10 by selling more than a million copies, and they were once again nominated for several Juno Awards. By this time Rush had sold more than 10 million albums worldwide.

Then in April the trio entered Le Studio to record Signals. The new material was becoming more keyboard-oriented and straightforward. "We've started streamlining a bit," Peart told Banasiewicz in an interview during the previous European tour. "Our songwriting now comes from a rhythmic point of view. We find a pulse that feels good and build our changes around it, whereas in the past we would find a melodic passage and put all the time changes around that until it became a musical octopus.

"My writing is much more concise now, and I'm interested in stating things more briefly and clearly."

Once several of the new songs, including "Subdivisions" (which would become the first single from the album), "Digital Man" and "Chemistry" were worked out, the band booked some European dates and once again put the songs to the live-audience test. Lee also fit in a guest appearance with Canada's Second City TV (or SCTV) comedy team of Bob and Doug McKenzie, providing vocals for their comedy album Single "Take Off." Lee and McKenzie had been friends in school.

Signals features great individual moments, but overall the album is a little too much of a departure from Lifeson's signature guitar sound.

"Certainly not all of our experiments have worked, but that's part of the learning process," Lee said in a 2002 Canadian TV interview.

"The music that was turning us on at that time was synthesizer-based," Lee later stated to Hit Parader. "So it led us in that direction. I wrote almost everything on keyboards instead of bass guitar."

While Signals seemed to be a step back for Rush musically, it would end up producing the band's highest-charting Single - "New World Man" (#23) - and their best-selling tour ever, including four consecutive sold-out shows at Wembley Arena. The trio received increasing amounts of airplay and press.

On the New World Tour the band expanded equipment and sold out shows across North America throughout the winter. Rush also became the first rock band to play five sold out nights at New York City's famed Radio City Music Hall. Once the tour played through, it was back to choosing their direction.

Rush decided that after 10 years of recording under the Broon, they were ready to see what a different producer could bring to the table. This was a very difficult decision for them to make.

"We had become so close to Terry," Lifeson told the Milwaukee Journal, "It was difficult to be sure about anything." Rush eventually brought in Peter Henderson, who had produced Supertramp's classic Breakfast In America.

The band already had a few songs worked out as they entered Le Studio in the spring of 1984 including "Distant Early Warning," "The Enemy Within" and "Red Lenses," but there was uncertainty with a new person in the control room. The band eventually felt more in control of the their music in the studio than ever before. World-famous photographer Yousuf Karsh shot the back-cover photo of the band, after Peart had stated he would like a "Karsh-like cover photo. It was Karsh's first-ever rock-band portrait, previously having worked with the likes of kings, presidents and world leaders.

Rush finished the recording in five months and released Grace Under Pressure in April 1984 - a welcome return to the more guitar-oriented, progressive style of Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures. The band embarked on another sold-out North American tour in May, featuring a new state-of-the-art laser-light show.

The tour was highlighted by a headlining appearance with Ozzy Osbourne, Gary Moore,.38 Special, and Bryan Adams in front of 60,000 fans at the Dallas Texas jam Festival. After the North American leg, Rush made their first trip to Asia, playing several dates in Hong Kong, China and Japan. It was a unique experience for the three, as the polite audiences would stand to applaud only at show's end.

Recording equipment changed each time Rush entered the studio, so for their next album they decided again to bring in someone new who was hip on all the latest technology. Along with a recommendation from blues-guitar great Moore, the band chose veteran producer Peter Collins, who had worked with the likes of Alice Cooper.

Released in the fall of 1985, Power Windows features stunning musicianship and covers a variety of topics including the corruption of wealth on "The Big Money," atomic bombs in "Manhattan Project," and experiencing Asia in "Territories." Exotic percussion, sweeping synthesizers and Asian-sounding keyboards all intertwine yet don't clutter the sound.

Along with the advancement in studio technology for Power Windows came the challenge of reproducing the music live on stage. Many excerpts from the album had to be pre-sampled onto discs for performances.

After a few months off the band started to get the "itch" again and got together with Collins in September at Elora Studios in Ontario. By Christmas Rush had 10 new songs.

"Each year we take a little more time to write," Lee later told Guitar World Magazine in 1988. "This time we took two months to write the demos. We worked every detail out before going into the studio."

In January 1987 the band again traveled to England's Manor Studios to record basic tracks for the next album, Hold Your Fire - this time recorded on the then-new compact disc. Hold Your Fire was released in September 1987 with the one major difference in Rush's music - their songwriting approach.

"I think the writing stage is more important now," Lee told Guitar World in April 1988. "Ten years ago it was playing the live show that was more important I look at myself more now as a musician in the compositional sense than one in the playing sense. Now, with all the advanced technology available, it opened up the creative process in the writing. Hold Your Fire has more melody and variety than Power Windows," Lee explained to Banasiewicz.

The Hold Your Fire tour began in November 1987 in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, where fans had been petitioning the band to play. As the tour continued through America, then Europe, Hold Your Fire would become Rush's seventh consecutive Billboard Top 10 Album release. When the tour ended in the spring 1988 Rush took their customary post-tour vacation, only this time around there would be another issue for Rush to think about besides the next project.

The band's contract with Mercury was due to end after the next release, a live album, A Show Of Hands, put together from the shows they had recorded during the Power Windows and Hold Your Fire tours.

"The [record] deal was over, and when we started to renegotiate, Doug Morris of Atlantic Records - who'd had an interest in Rush for quite a few years - made a bid for the band," Lifeson told Kerrang! Magazine in 1990. "When it came down to it, we needed a change. We needed to be somewhere fresh."

Rush searched for a new producer and continued to work on demos. When Lifeson and Lee had started the writing process, they'd asked themselves what the true essence of the band was and decided it was the guitar.

"We wrote the music with that in mind, just bass and guitars like the old days," Lifeson said. "It was more direct-sounding. We just added keyboards for color." They decided on Rupert Hine, whose credits include Tina Turner, Stevie Nicks, and The Fixx.

"Rupert came down after doing production work for Stevie Nicks and didn't realize how prepared we'd be," Lifeson said. "We finished ahead of schedule...It was the first record in a long time that we really had a lot of fun making."

Songs such as "Superconductor" and "Scars" put the guitars more in the forefront, a return to Rush's power-trio roots. As the band started their North American tour to support Presto, Mercury Records released Chronicles, featuring material from Rush's back catalog. This surprised the band because their obligation with Mercury had ended with A Show Of Hands.

The Presto tour continued throughout America and Canada for several months before the band took a break from the road. While at home Lifeson, Lee, and Peart each began working on ideas for the next project, then gathered at an Ontario farmhouse-studio to work on demos for three months before recording.

Their 14th studio album, Roll The Bones, was released in the fall of 1991. Although it remains in the same vein as Presto, Lee sings in a low register.

"In the old days it was a trademark of the band for Geddy to be a screamer," Lifeson told Guitar World. "But over the years it became a terrific strain on his voice to sing like that. Now he wants to be more of a pure singer. His sense of melody and harmony has really developed over the last few records."

One pleasant surprise from Roll The Bones is the band features their first instrumental track since "YYZ" - "What's My Thing?"

"I really like it, but it almost didn't make it to the record," Lee told Guitar World in 1992. "Every time we started writing an instrumental, it would somehow turn into another song."

As Rush did their customary tour across North America through the end of 1991, Roll The Bones would reach #3 on the Billboard Album chart.

"I was worried five years ago that we wouldn't leave any mark," Peart told Spin Magazine at the time. "That it would all be for nothing."

Rush entered 1992 by taking a post-tour break to spend time with their families, but it wasn't long before the band started thinking about the next project. After working out some demos they entered Morin Heights Studio in Ontario, bringing back producer Collins and introducing engineer Kevin "Caveman" Shirley to the recording sessions. Shirley had produced and engineered some of the biggest names in rock including Aerosmith, Iron Maiden, Journey, and Jimmy Page.

With the band wanting to stay with the guitar-oriented sound of the last few albums, Shirley encouraged a more live approach to Lifeson's guitar work by having him record his guitar parts in the studio instead of the control room.

"For a long time I maintained you could get the same results from the control room as in the studio. I know now that I was completely wrong," Lifeson told Guitar Magazine in 1994.

Rush's 15th studio album, Counterparts, was released in the fall of 1993 and would reach #5 on the Billboard Album chart, making it their 10th consecutive Billboard Top 10 album. With the new album also came another sold-out tour that carried them into the spring of 1994.

"We've bridged so many stylistic and technical changes over the years," Peart recalled. "It's incredible that we've made it this far, just because there's so many factors involved. The personal willingness is just one factor. Just because you want to have a 20ˇyear career in music doesn't mean you will have an audience or a record company for 20 years."

Rush took an extended vacation after the close of the Counterparts tour; Lee's wife had a baby in May, and he wanted to take a year off. It was during this break from Rush that Lifeson decided to record a solo album.

"During the recording of the last Rush record I had thought of doing a solo project, when I would have the time and opportunity," he said in an online interview at the time. "And here was that opportunity." Lifeson would record Victor over a 10-month period from his home-based Lerxst Studio just north of Toronto. He recorded a lot of the material on his own, before bringing in various local session musicians to help finish out the project. Primus' Les Claypool also makes a guest bass appearance. Lifeson provides a few vocals and recruited Edwin of the Canadian band I Mother Earth for most of the tracks.

"We've established a pattern over the years in Rush, and I wanted something new that was going to push me," Lifeson said. "I've always loved everything we've done as a band, but when you work with other people there's always compromise for everyone involved. Over the years I've learned that if I do hear something in my head as a complete version, I needed to find another way to get it out?to get it out of my system and hear it exactly like I had always heard it in my head."

Victor is a diverse, aggressive affair, something the typical Rush fan probably didn't expectl. "I set out to make a record that was disturbing. I didn't want to make a record that would typically be made by someone like me, from a band like Rush."

Tracks such as "Don't Care,'" "Promise'" and "I Am The Spirit" have an industrial-rock feel to them. There are also two instrumentals, "Mr. X" and "Strip And Go Naked," that feature some explosive guitar work, clearly stating that Lifeson hadn't forgotten where he had come from. Another reminder would come via Rush's election to Canada's Juno Hall Of Fame.

After their extended rest period, Rush started to put together ideas for a new album toward the end of 1995. This time around Peart wrote about global concerns, with subjects ranging from the Internet life in "Virtuality'" and comparative religion in "Totem." The band also checked in with another instrumental, "Limbo," which starts with the sounds of a bubbling cauldron and bursts into a soaring array of guitars, synthesizers and disembodied voices - even a bit of dry humor in the form of a sample from the '60s novelty song "The Monster Mash." Who says Rush take themselves too seriously?

Test For Echo was released in October 1996, and Rush embarked on yet another North American tour. By this time the live show had become a challenge requiring incredible concentration.

"Watch what everyone is doing on stage," Peart told the Boston Globe at the time. "Alex and Geddy are triggering keyboards and bass with foot pedals. I'm triggering keyboards through drum pads. It all takes an enormous amount of work just to choreograph."

The Test For Echo tour continued steadily for six months, culminating in July 1997 with shows in their native Ontario. In July, Peart lost his daughter Selena in a car accident -she was only 19 years old. Then, his wife Jacqueline Taylor succumbed to cancer just seven months later. Thus, Peart took an extended period of time away from the band. He traveled abroad on his motorcycle - and He took notes, lots of notes.

The intensely private man later released a book titled Ghostrider: Travels On The Healing Road (published by Canada's ECW Press), which features prose, letters to friends and daily journal entries. Peart traveled more than 55,000 miles - from Quebec to Alaska, down the Canadian and U.S. coasts, through Mexico and Belize, then back to Quebec.

"It was hard for me to accept that fate could be so unjust, that other people's lives should remain unscathed by the kind of evil that had been visited upon me."

During this time, it was unknown whether Rush would ever record or perform again. In solidarity with Peart, Lifeson and Lee refused to reveal the future of the band to the press or the fans, saying only that their friend's well-being was the only priority.

"We just tried to be there as much as he needed us?we're kind of his extended family,'" Lee said during a Canadian TV interview. "Neil is a pretty solitary guy and he handled alot of it on his own, but not all of it."

Different Stages, a live album taken from ˇil the Test For Echo tour, came out in 1998, and they were awarded one of their native country's highest honors - The Order Of Canada. Recognized for raising millions of dollars for charity over the years, the honor acknowledges "significant achievement in important fields of human endeavor."

"I'm just a musician in a band," a humble Lifeson told the Toronto Sun after the event.

With Lifeson having a couple of projects going on, including producing a young Pennsylvania band named Lifer and playing in the house band The Dexters in the club he owns, The Orbit Room, this gave Lee a chance to write on his own.

"While Rush was touring in 1997, I went to Vancouver to hang out with my longtime pal Ben Mink," Lee told Bass Player in 2001. "We had always joked about playing together, so we went into his home studio and jammed. We then made a commitment, and over the next year and a half we got together every three months to write."

Eventually Lee and Mink had a half dozen songs in good shape but didn't really know what to do with them.

"At the time, I didn't have a taste for my own record," Lee said to Bass Player. "Finally I sent the songs to my buddy Val Azzoli at Atlantic Records who said, 'Don't be an idiot - make a record.'"

In the fall of 2000 Lee and Mink produced what would become My Favorite Headache and brought in Soundgarden and Pearl Jam's Matt Cameron to play drums.

"I hadn't written lyrics since Rush's early days basically, because Neil is so good at it," Lee said. "I was a little self-conscious at first, but once I got over the shock of hearing my own words coming back at me, it was great.

My Favorite Headache leads off with a thunderous bass rumble. "At the end of the day, I am still a bass player before anything else," Lee said. "So I thought it was an appropriate way to kick things off."

From there the music goes off in different directions, displaying Mink's biting guitar in "Runaway Train," Cameron's unique percussion style in "Moving To Bohemia" and the powerful "Grace To Grace."

In 2001 Peart became reacquainted with his bandmates.

"I think the phrase that he used was, 'I think it's time for me to seek some gainful employment,'" Lee said in a Canadian TV interview, "which I thought boded well for the future because it was so funny."

The three members of Rush hadn't played together since the Test For Echo Tour ended in 1997.

"After all of the difficulties of the last number of years, when we came and looked at each other, there was a great feeling of affection because we had been there for each other through this tough time," Lee said. "And there was also a great respect for each others abilities as musicians."

With Lifeson and Lee's solo experiences, the band decided to produce the record themselves. "This was the first record where I sang all my vocal parts on my own without the benefit of a producer, engineer or peanut gallery," Lee said in a CNN interview.

Rush emerged 13 months later in early 2002, with their 17th studio record and 23rd official release overall - Vapor Trails. The album is a vibrant blend of detailed progressive rock mixed with a refreshing alternative-punk kind of vibe. Peart thunderously kicks off the album's first track, and first single, "One little Victory," making a triumphant return.

"It was an important statement to make," Lee said. "We're back, and we're celebrating something here. Especially for Neil, just the fury of his playing was just the right thing to do." Peart's personal tragedy and healing come through in "Nocturne," "Ghost Rider" and "Sweet Miracle."

Rush began the Vapor Trails lour in March 2002 and performed shows to legions of their loyal fans throughout the year. They also gave longtime fans a treat by bringing back a few Rush classics.

Before a show at New York's Madison Square Garden in September 2002 the band received a Record Industry Association Of America (RIAA) achievement award for selling more than 25 million units in the United States, making Rush the top-selling Canadian band in U.S. history. All of their 20 studio and live releases have gone gold or platinum, and they were recently inducted in the Canadian Rock Hall Of Fame. Rush became eligible for induction into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1999.

In December they visited Brazil for the first time and played before 60,000 fans in Rio De Janeiro, with the show being recorded for an upcoming DVD release in the summer. Also a new greatest-hits package, The Spirit Of Radio: Greatest Hits 1974-1987, was released earlier this year.

"There's a lot of respect for each other within the band," Lifeson said in a Canadian TV special in 2002. "And I think that comes from being together for over 30 years in a business that is notoriously short-lived."

Rush has truly persevered.

Album Review

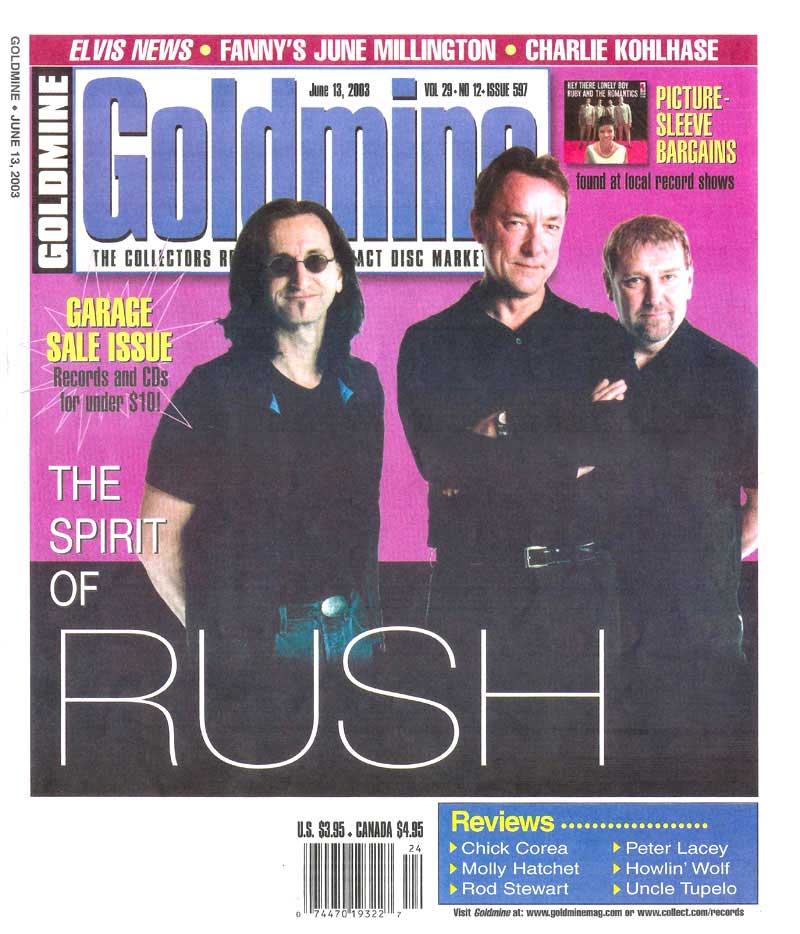

RUSH

The Spirit Of Radio: Greatest Hits 1974-1987

Anthem (668251982)

It's darn near impossible to get excited about a greatest-hits album, especially if it's from a band one has followed intensely for 27 years (finishing the math, Rush is 29 years old), But it's kind of cool that The Spirit Of Radio: Greatest Hits 1974-1987 is indeed only the second hits-type package from Rush and the first that is truly about the hi LS. One disc and bam - 16 tracks of anthemic mullet mania from Anthem, the little Canuck label built around the band. Obviously, with the above title, the door is open, carpet unfurled, for a second half to this story, although the hit-ness - both commercially and creatively - drops off precipitously 14 tracks into this album, ending with 1985's "The Big Money."

Despite that, The Spirit Of Radio is a sparkling, stellar introduction to the band, a collection of Rush's great choruses, their lighter-foisting moments and their shorter, more accessible tracks. Every album is sampled, save for Caress Of Steel (what, no "Bastille Day"?), with the triumphant trinity from Moving Pictures - "Tom Sawyer," "Red Barchetta" and "Limelight" - showcasing and solemnly guarding the effervescent lifeblood of this band that dared to force impossible progressive-rock calculus upon the previously unforgiving logistics of the power-trio format.

Still, my favorite of the catalog is the transitional album Signals. Two tracks hail from that record, both songs bonafide hits "Subdivisions" with its take on suburban ennui, and "New World Man," an interesting backhanded homage to The Police, demonstrating that the band is about to follow their tangents, their complicated muse. Hang on tight.

The Spirit OJ Radio collection is tastefully packaged as well, if not forthcoming and eerily "quiet" (i.e. no liner notes). It's comprised of credit-laden discographies, chart positions, nifty radio graphics and a smart couple of photos, the second a re-creation of the earlier one, a lot of years and a few personal tragedies later.

- Martin Popoff