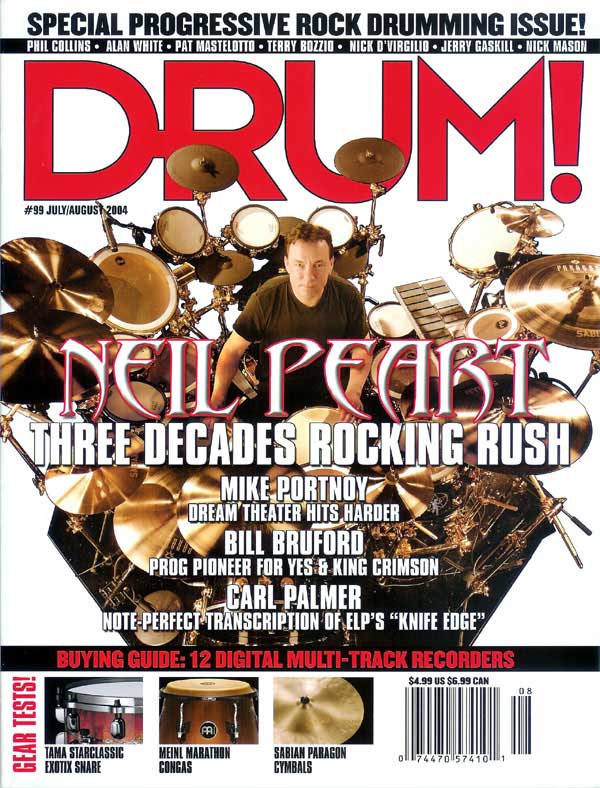

Neil Peart: Progression Personified

By Don Zulaica, DRUM!, July/August 2004

- Neil Peart: Progression Personified

- Lorne "Gump" Wheaton: The Professor's Tech

- The Freddie Factor

- Peart's Domain

Not only has Rush - bassist-keyboardist-vocalist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer-percussionist Neil Peart - enjoyed a 30-year career, with 17 studio albums, five live recordings, countless accolades and awards, they've done it on their own terms, and with the same lineup. How many progressive bands, or bands, period, can say that?

Yes? No. Genesis? Ask Peter Gabriel. Dream Theater? Dream on. Kiss? Even on their umpteenth farewell tour, at full bore they're 50 percent of the hottest band in the world.

There were times when a fourth member seemed necessary, with all of the instrumentation gone wild, and it never happened. Then there were the well-documented tragedies of the late '90s (Peart lost his daughter in an automobile accident, and his wife to cancer), the solo projects by Lee (My Favorite Headache) and Lifeson (Victor), and cloudy skies regarding the band's future. Of course, as evidenced by double-bass barrage of the opening bars of "One Little Victory" from 2002's Vapor Trails, nothing was over, and the band enjoyed a long reacquainting tour that was documented on the Juno-winning CD/DVD Rush In Rio.

At press time Rush was putting finishing touches on a project they're calling Feedback ("because when Geddy and Alex were working on demos they decided to have feedback and backwards guitar on every song"), an EP of covers that is slated to include The Who's "Seeker," Buffalo Springfield's "For What It's Worth," and Cream's "Crossroads." They're also currently celebrating their 30th anniversary with yet another world tour.

"The Professor" is back.

Freedom To Progress. Hard to believe it was 1974, July if you want to be more precise, that Peart replaced Rush's original drummer John Rutsey, who played on the band's self-titled debut. Lee, Lifeson, and Peart were looking to stretch their boundaries beyond the Zeppelin, Who, and Cream influences of their youth. To "progress" before there was anything really known as "progressive rock." Luckily, the late '60s and early '70s afforded the band, and the young drummer, the freedom to do just that.

"It was so challenging," Peart fondly remembers. "When I was starting to play drums in the early '60s, all you had to know was a 4/4 backbeat and 'Wipeout.' That really was all a drummer needed. But by two or three years later, suddenly there are odd-time signatures, complicated and ambitious arrangements, exotic percussion instruments coming into it, and as a teenager, I'm going, 'That's what it takes to be a rock drummer.' Then it ramps up again, 'That's what it takes to be a rock drummer.' To be a young drummer at the time, it was daunting in a way, but so stimulating. All the bands I was in, we were free."

That freedom helped propel a new wave of rock musicians, with perhaps a little more emphasis on the word "musician." It wasn't a bad thing to put the two words together - yet.

"The idea of progressive rock," he muses, "before its pejorative sense, probably I'm guessing, [began in the] early '70s with the wave of keyboard bands - Yes; Genesis; Emerson, Lake and Palmer. That era was a little bit later, and definitely a post-'60s scene, and with whole other influences of bringing in classical and more obvious jazz influences into it, where I would say the late-'60s was very much blues-based and psychedelic. That change in the early '70s, that's when I think you started to hear the idea of progressive rock, and meaning something very true.

"As young musicians we were learning more and wanting to use it more, and wanting to apply it more, and nobody ever played down to the audience. There was no lowest denominator, no simplifying for the sake of the audience, no making the songs shorter for the sake of radio. So there were no compromises in the sense, [saying that the environment was freer then] sounds kind of clichéd and trite, but in fact it was truly true that we could make a living playing this ridiculous music."

Peart smiles as he says the word "ridiculous," recalling early gigs with cover bands around Toronto. "Once a week we had a jam session at the local alternative cultural coffee house, and we got paid $10 each to go there on Thursdays and jam. How perfect! $10 was several pairs of drumsticks, or a down payment on a new cymbal to replace that cracked one. But considering the fertility of it as a breeding ground: we were doing endless blues jams, endless freeform Doors epics and all that, getting modestly paid, and having an appreciative audience for it.

"That did die out. And when progressive rock became over-bloated, and as always too, when the true believers were overrun by fakers and marketers and all that, then too it started to get bloated beyond reason, and it had to be torn down."

Evolving Past Prog. Eventually at some point during the '70s the word "pejorative" (and others we can't print) became more fashionable when describing progressive rock, but while other bands seemed to get buried in excess, Rush honed and evolved their sound. And in the process, while still imbibing the many influences around them, they discovered the secret to their longevity: pleasing themselves.

"It very much coincides with our first popularity," Peart says of prog's beginning-of-the-end, "which worked to our credit, because we came out of the late-'60s base, so we had the blues-influenced heavy rock thing. And when we started incorporating those so-called progressive ambitions of wanting to make it more complicated, more interesting, more fun to play ...

"Let's get back to that for a minute, it was fun to play. I wanted to play music because I loved to listen to it, that's my fundamental relation. It's the same reason I love to write books, I love to read. It's a simple reaction to something that I love. So when we were able to play music that was fun to play, that became one of the building blocks of what Rush is. And because we've toured so much, especially, we've wanted music that was fun and challenging to play live night after night, and never got stale. We've never had to fake it. Occasionally we'd retire a song if it felt a bit stale, and then bring it back later, and it would be refreshed. But for the most part, they were such true reflections of what we liked in music, what we liked to create and listen to and hear and play, that the freshness and sincerity, I think, endured. We were able to straddle that turning point through the '70s, partly because we already had a loyal audience, but also because we weren't one of those keyboard-based progressive bands. We were still a rock band, you know? We still had that credential, if you like.

"Plus, we responded to it. A lot of the old guard said at the time, 'What am I supposed to do, forget how to play?,' [during] the whole new wave revolution, when simplicity and repetition came back, and for good cause. It was great that they did, and we responded to them as listeners. Again, being young enough and listening to records that came out, I was able to respond in exactly that way: I love this music, I want to play it, let's bring it into our music. So we went through an evolution through that revolution, we had the luxury of being able to evolve through it and absorb the best of it, never mind the pretense, the stance, the pose, or the fashion of it. Just the musical part, we absorbed into ourselves. And then we experimented through the late-'70s and then finally, I guess, with Moving Pictures [1981], that should be our first album, because that's where we cemented that approach."

Ah, Side 1 of Moving Pictures (see, a long time ago there were these things called records, which had two sides, but we won't get into that right now). Go into any music store's drum department and throw a rock, and you're liable to hit somebody who was influenced by "Tom Sawyer," "Red Barchetta," the instrumental "YYZ" (it's the code for Pearson International Airport in Toronto, you hoser), and "Limelight." It was here that Rush found their perfect balance, jamming distinct musical signatures and verbiage into shorter songs. But that wasn't before a period of churning out lengthy concept pieces like the 20:33 epic "2112" and the 18:04 "Cygnus X-1 Book II" from 1978's Hemispheres.

"By Permanent Waves (1980) we had started to change, but we had already decided at the end of Hemispheres that, 'Okay, that's the end of that.' We had verbalized it. We were very self-aware at the end of Hemispheres. We wanted to move on. Then in 1978 and '79, things are changing so much in music around us, and again, being music fans and listening and responding to it - and wanting it, wanting to do it - 'Spirit Of Radio' was a huge step in that direction. It was of course a deliberate attempt to encapsulate all the different threads of modern music that we thought were cool. So that moved on, and we were of course still playing around with the epics at that time, with 'Jacob's Ladder' and 'Natural Science' and all that, but they were taking on a different focus. Moving Pictures became truly focused. Where we could be concise and ... overblown at the same time [laughs], which was what we had been looking for, obviously. That became the foundation for everything that followed through the '80s."

"With all humility, I like most of what comes after Moving Pictures. I was talking before about songs being designed to play live and be challenging, 'Tom Sawyer,' right off the top - I never get tired of it, it never gets easy, and it's always challenging. I've changed tiny little baby details in that song over the years, but almost nothing from that drum part fails to satisfy me now, as a player or as a listener. So things like that, from the '80s on really, I think we started to learn so much about musicianship, about composing, about arranging, and consequently the records became much more satisfying."

Irresistibly Useful. Anyone who has followed Rush over the last three decades knows they never trapped themselves in any one musical genre. The bluesy riffs of Rush gave way to longer, denser passages like Fly By Night's "By-Tor And The Snow Dog," and eventually "2112." By that time, the band's studio prowess was making live duplication an arduous task, and a question emerged: should they add a fourth member?

"That arose as early as '76," Peart explains. "We started talking along those terms, 'we want more,' and how to get it. Fortunately our progress happened to mirror technology's progress, so that as Taurus pedals and synthesizers came along, and later on sampling, sequencers, and all that, they became tools that we could use to keep expanding and growing without [adding another band member]. Obviously it made a lot of work for everybody on stage, but we've evolved now to where all of us are triggering things, and everything is played in real time, by us."

Early on this meant Neil's kit would expand to encompass various bells, temple blocks, timbales, and even a glockenspiel. In the '80s those would be replaced by electronic drums - at first Simmons pads, and now Roland V-Drums, various samplers, and a malletKAT. But Peart doesn't pretend that he's any kind of a technology groundbreaker.

"Other people did the pioneering," he confesses, "like Bill Bruford and Terry Bozzio. I always considered myself like Henry Ford: watch what everybody else does, and then 'Okay, it's ready now.' I don't really like to pioneer, but once I realize that something is irresistibly useful musically, like Simmons drums were and later electronic drums and sampling - I mean, to be able to have every percussion sound in the world, and some that you make yourself, to have that available under your hands and feet, it was irresistible. I'm not really a technology lover, but its uses as a tool just became irresistible to me."

Getting Away With It. In their history Rush has sponged elements of prog, new wave, even funk and reggae, mixing a concoction that's unmistakably their own. In these days of rock bands that are here today and gone later this afternoon, it's a testament to their ability to maneuver around music business landmines. They got away with it, and still are, but does that same career opportunity exist for younger groups today? Peart leans forward in his chair, eyes widening, "Of course! Absolutely. There's a band called Porcupine Tree. They're British. Excellent band. They have a song called 'The Sound of Muzak' [from In Absentia, 2002], and the chorus goes, 'One of the wonders of the world is going down ... and no one cares.' It's music that they're talking about. And the whole song is in seven; the drummer [Gavin Harrison] is so elegant. Beautiful player. Lovely guitar player. It's modern, progressive rock music. Completely unheralded, completely below the radar.

"There's an American Band called The Mars Volta [Jon Theodore]. Again, they're getting away with it, these guys. It's so great to hear. Their music is so sincere, it has both sophistication and energy. You know, I was talking before about those qualities that we grew up with, that wild abandon of rock music, but at the same time wanting it to be more sophisticated both as a musician and a songwriter, and the lyrics, all that stuff, is up to every modern standard possible. It's absolutely free, uncompromising music. Yes, it still exists. These guys have records out."

And then there are groups whose independent thinking routinely gets compared to Rush, like Tool. "Yeah, perfect," Peart says, nodding with palpable admiration. "They're getting away with it too. It takes courage. You have to say, 'No, I'm not doing that lowest common denominator thing, no we're not making seven sets of demos for the record company until they get bland enough for them. No. We're doing it our way and if we have to do it in the clubs and sell our records out of the back of the van, we'll do it.' It's the bravery. I've always loved the quote, 'There are no failures of talent, only failures of character.' We've often remarked that the hardest word to learn as a young musician is 'no.' Because when you're coming up, all you want is ... if anybody asks you, 'Yes! We'll play at the bar! We'll play in your rec room! We'll play at the church hall! We'll play at the high school! Yes! Yes!' We'd have one gig a month when I was in high school, and we'd be waiting all month for that gig.

"So when the supply and demand starts to change and people are wanting more out of you, to learn to say 'No, I'm not doing what you say,' or, 'No, we can't play three shows on one day, and then drive 600 miles and play three more,' it's hard to learn that. It feels kind of arrogant, when you've grown up just so hungry for attention, and suddenly you turn around there's too much attention, you don't feel like it's your right to back off and say, 'No.' If I need privacy, or we need control of our own destiny, 'we don't need anyone to tell us how to make records or how to write songs, we're doing it our way, and shut up,' that takes a certain amount of strength and determination. And if people fail at that aspect of it, then it's their failure."

The Obvious Question. It's been asked before, and it will be asked again: Did you ever think you'd be at this point 30 years after meeting Geddy and Alex?

Peart shakes his head with a wry, disbelieving smile, "Oh God, I was just writing that people say to me now, 'Did you ever think when you were starting out that you'd be playing in arenas in front of thousands of people?' No. I dreamed of playing at the roller rink. I dreamed of playing at the high school. Those were my dreams. I wasn't an idiot. You can't have fantasies. If you have dreams, they have to be attainable goals. And the next goal became to play at Massey Hall in Toronto. Did I think about Madison Square Garden? Did I think about Wembley Arena? No! You don't. That's silly. You have to set the next goal from where you are, so as a kid my dreams were absolutely that small. Even in the band, joining and playing our first tour would have been enough of a lifetime if I'd had to go back to selling farm equipment parts after that. Fine. You can't, obviously, think in those terms. No one can. Life doesn't work that way.

"And especially in the so-called entertainment business, you can't plan a career. You can't plan for an audience to like you for 30 years. It's up to them. You can do your best and try to make your music as good as you can, and hopefully people will like it, and there it ends. After that, it's up to them."

Lorne "Gump" Wheaton

The Professor's Tech

By Don Zulaica

At the heart of Peart's monster kit is one Lorne "Gump" Wheaton. Although he joined the Rush touring family as a carpenter for the Test For Echo tour, and officially became a studio tech during the Vapor Trails recording sessions, Wheaton's history with the band goes back to the '70s when he worked with Max Webster, a frequent Rush support act at the time.

What makes him Peart's go to guy, is it technical knowledge? Intuitiveness? Speed? "It's mostly interpersonal," Peart says. "Those kind of relationships, of course, anybody you work that closely with, that's probably more than 50 percent of the importance. Lorne has that kind of character that's wonderful to work with on a daily basis. His technical expertise extends beyond putting the drums up; he has a great sense of tuning. Even during the Vapor Trails sessions, he would be in the control room when I would be trying different snare drums through the demo part of the process. I was trying drum parts and along the way different snare drums, and I found I could rely on his judgment of what snare worked for what song. That's a sophistication that he has in his ears. Just yesterday we were discussing one drum, the 12" x 8" tom, and he said, 'You know, I think you should bring the pitch up a little on that.' Again we're talking about the tuning of one drum, and I let him do it because it's something he's doing every day, so I'd rather him bring it up a notch, and he did and we both agreed that it was better."

Ears are always good, but sometimes in the heat of battle speed and efficiency are important, especially when you're dealing with a player-surrounding kit like Peart's. "To get into Neil's rig is very interesting," Wheaton explains, "because there's no room in there for anything but himself. What happens is, he'll play the piccolo snare if the main snare goes down, and I'll just tell the monitor guy and everybody in the band through their in-ears, 'We've got to do a snare change, so stretch it.' Neil will get off the kit, I'll throw another one up, and take off. That's the only way you can do it, because you can't get into his kit otherwise."

For the record, the nickname "Gump" has nothing to do with Bubba Gump Shrimp or Tom Hanks. Remember, these guys are from Canada, and up there they like this thing called hockey. Peart laughs, "When we were all children, there was a goalie called 'Gump' Worsley, his nickname as a player was 'Gump,' but we always knew his real name was Lorne. So Lorne had to become 'Gump.'"

The Freddie Factor

By Don Zulaica

In the mid-'90s Peart put together a who's who of drummers (we're talking from Bill Bruford and Kenny Aronoff to Matt Sorum) to record two tribute albums of Buddy Rich material with the late legend's big band. During the Burning For Buddy sessions he noticed newfound fluidity in one Steve Smith, and asked him where it had come from. Smith gave Peart a one-word answer: Freddie.

Gruber's impact on Peart led to drastic changes in his setup and technique, including recording all of 1996's Test For Echo using traditional grip. Why mess with something that seemingly wasn't broken?

"It was so serendipitous," Peart explains, "meeting Freddie at just that time when I was a little bit hungry for growth and didn't know how to accomplish it. Meeting him and being able to take the time to practice every day, I had to trust in the idea of it.

"Freddie didn't tell me what he was going to do. He didn't tell me, 'Here's what I'm going to show you. Here's what I'm going to make you into.' He just started giving me the exercises. So it had to be an act of faith on my part to allow him to lead me. And eventually I would see where he was leading me, as in one of his quotes 'to put the pieces together.' As I started to take these isolated moves and choreograph them and mix them into a whole physical choreography, I started to understand where he was taking me. It had to be my realization, 'Oh, I get it!' So a lot of it was that kind of process and progress through it all."

But as anybody who has seen the Rush In Rio DVD can attest, Peart's back to playing matched grip much of the time.

"What was interesting too at the time of Test For Echo, that I haven't really recapped since, is that I went completely to traditional grip, just because he was leading me that way. And I thought, 'Why not?' I'd learned that way, all my rudiments I can still really only play well in traditional grip, so I thought, 'Why not see where this goes?' When I asked Freddie [about grips] he said, 'It doesn't matter.' So I decided to take the fresh way, and deliberately recorded Test For Echo in traditional grip. And all those songs, I still can only play that way because they're designed that way. So that immediately gave me a completely fresh approach.

"And yet I had found that once I had developed that, I didn't pursue it anymore. I went back to matched grip, with the exception of things that I can just do better with traditional grip. I've never tried to switch 'Tom Sawyer' to traditional grip. The songs that I recorded on Test For Echo with traditional grip, have stayed that way. But after that, on Vapor Trails, it's all matched grip, with the exception of some rudimentary stuff."

Warming Up. Before sound check I like to go in and play for 20 minutes or a half hour, and then before the show, same thing. It's both mental and physical. It calms and centers me as well as getting me more fluid. The whole day takes on its own dynamic. After 30 years of it, there's an internal dynamic that goes on from the moment you wake up that day: it's a show day, everything is subservient to that. Your whole day just funnels like a vortex towards that 8:30 show time.

Butterflies. I am always tense, nervous in the sense of being apprehensive. Buddy Rich's sax player Steve Marcus was telling me a story that at the side of the stage, Buddy, in his 60s, would show him his hands, which were shaking, and say, "You'd think after all these years..." But he was still nervous, Buddy Rich. This is what it takes to be serious about it. That's the lesson of it too, and that never goes, I don't think. Not for me, anyway. When I walk on to that stage, there are two motivations: there's anxiety about hoping it goes well, but there's also a determination that this is another chance to get it right.

Developing The Signature. The most important thing I learned as a teenager was when I was starting to get into my first bands, and wanting to be in a cover band that played Who songs because they were my favorite band, and then discovering I didn't like it. I didn't like playing those songs, because it wasn't me. It wasn't my personality. That was the first lesson in developing my style, realizing that I wasn't happy imitating even my hero, I thought. That's not what I wanted to do. That's not what felt comfortable, to me. That's where character dictates style. The kind of person you are, if it's sincere, is going to dictate the way you play.

Still, Moon Rocks. I admired Keith Moon and was so excited by this abandon and playing at the time. I heard the single of "Substitute" the other day, and it's true, it's revolutionary, nobody played like that back then, you know? And as he refined that, however deliberately or not doesn't matter, but the way he's playing by Tommy is so musical, so sublime, so fluid. Regardless of ebb and flow of tempo, it doesn't matter. It's so musical.

Danny Carey Rocks, Too. Oh, great, great drummer. I love his playing. They have a song called "Schism" that's in seven. He plays a pattern in there, it's one of those things, a little detail, he drops a crash cymbal on the perfect beat, as the time signature goes around. It's those kind of things, where it's not only technical mastery, but a sense of musicality and dynamics that I admire. Energy and sophistication-that's the stuff. There are a lot of young guys around now with energy, but not too much control.

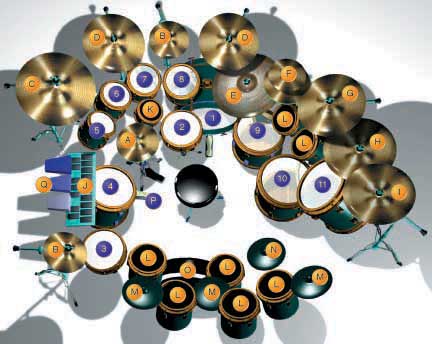

Peart's Domain

Drums: Drum Workshop

1. 22" x 16" Bass Drum

2. 14" x 5" Solid Shell Snare

3. 13" x 4" Snare

4. 15" x 13" Tom

5. 8" x 7" Tom

6. 10" x 7" Tom

7. 12" x 8" Tom

8. 13" x 9" Tom

9. 15" x 12" Floor Tom

10. 16" x 16" Floor Tom

11. 18" x 16" Floor Tom

Cymbals: Sabian Paragon

A. 13" Hi-Hats

B. 10" Splash

C. 20" Crash

D. 16" Crash

E. 22" Ride

F. 8" Splash (top) 14" Hi-Hat (bottom)

G. 18" Crash

H. 20" China

I. 19" China

Electronics:

J. malletKAT

K. Dauz Pad

L. V-Drum Pad (set inside a DW shell)

M. V-Cymbal Pad

N. V-Drum Hi-Hat Pad

O. V-Drum Bass Drum Pad (set inside a DW shell)

P. Shark Trigger Pedal

Rack:

Roland TD-10 Brain w/Expansion Card

Emu 5000 Samplers

Percussion: Q. Cowbells

Neil Peart also uses Remo heads, Pro-Mark 747 Neil Peart model sticks, and DW hardware and pedals.