Working, Man!

Guitar World's Bass Guitar, August/September 2004

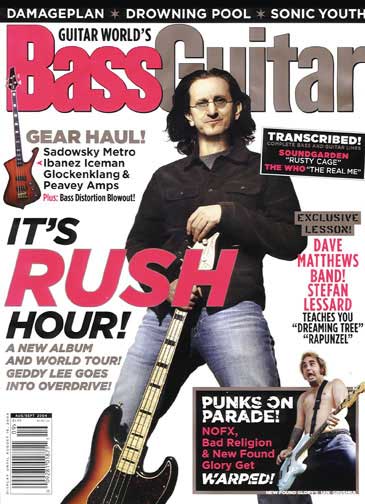

With their new EP of Sixties classics, Feedback, and their first world tour in what seems like an eternity, Geddy Lee and Rush fulfill their 30 years of prog-rock greatness with a milestone for the masses. We get the skinny on Rush's lean lord of loud, from his Jazz Basses to his junior-high jams.

With a new covers album, Feedback, shipping to stores, Rush are back on the road and Geddy Lee's bass is back in the driver's seat. Bass Guitar's J.D. Considine rides shotgun.

NO ONE PERSONIFIES RUSH AS COMPLETELY AS Geddy Lee. Between his tart, idiosyncratic vocals and busy, melodic bass lines, Lee has been at the heart of the group's sound and sensibility for three decades, from the Zeppelin-esque thunder of 1974's "Working Man" through the neoprogressive rock moves of 1980's "The Spirit of Radio" to the seasoned virtuosity on view in last year's stellar live concert DVD

Lee's look - tall and gaunt, with a prominent nose, long brown hair and omnipresent shades - is rock-star distinctive, providing the band with its most memorable visual feature. While drummer Neil Peart may have written most of Rush's lyrics, it's Lee who has sung them, in a high, reedy tenor that suggests both Robert Plant and Yes' Jon Anderson, making quirky sound bites like "The sound of salesmen!" and "We are the priests!" part of a secret rock lexicon. And while he may not be a household name on the order of fellow Canadians Neil Young or Bryan Adams, Lee has become the archetypical Canadian rock star. Who better to sing that country's national anthem on the soundtrack album to South Park: Bigger, Longer, Uncut?

His singing may be a talking point, but the reason Lee graces these pages is that he is, quite simply, one of the greatest bassists in rock. Blessed with a style inspired by the relentlessly riffing improvisations of Jack Bruce and the guitaristic virtuosity of Chris Squire, Lee long ago obliterated the divide between boringly functional bass lines and flashy solo spots. Instead, he has set a new standard for active, fluid playing that still works as accompaniment. Remarkably, the high standards he set on such albums as 2112 and Moving Pictures have been surpassed on Rush's 2002 studio disc, Vapor Trails, Lee's unsung 2001 solo album, My Favorite Headache, and the band's brand-new eight song EP, Feedback, which finds Rush covering the Sixties chestnuts - from bands like the Yardbirds, Blue Cheer and the Who - that they often played as budding teenage garage rockers.

Simply put, Geddy Lee is a player's player, the bassist that countless kids (and more than a few pros) have emulated and still want to be when they grow up. It isn't just that his bass lines are complicated and technically demanding, or that his tone breaks the sound barrier between lows and mids without sacrificing either. Above all, Lee's lines are melodic, even singable, which is why his parts on such tracks as "La Villa Strangiato," "YYZ" and "Tom Sawyer" are woodshed standards and rites of passage for budding players still. That he can play all that and sing at the same time seems almost unfair.

In the 30 years since Rush released their self-titled debut, Lee and his band mates - Peart and guitarist Alex Lifeson - have become icons for a generation of artistically ambitious young rockers. Smashing Pumpkins, Tool, Primus, Coheed and Cambria, the Melvins, the Mars Volta ... Rush have cast a long and pervasive shadow across the modern rock scene, even if the hipster critics who help define "alternative" taste would likely never see it that way. Rush were themselves heavily influenced by the likes of Cream, Led Zeppelin and Yes, but the band has somehow continued to evolve over the course of its 25-album, 30-year career, resulting in three musicians who are today very different players.

Back then they were just a couple of middle-school kids with Eastern European names, living in the Toronto suburb of Willowdale. One was Gary Lee Weinrib, whose nickname, "Geddy," was provided by his Polish grandmother's Yiddish pronunciation of his name. The other still answered to Alex Zivojinovich, which he later changed to Lifeson, the more-pronounceable translation of his Serbian surname. After several instances of borrowing Lee's amp for his fledgling band, Rush, Zivojinovich finally borrowed Lee's talents for a seventh-grade gig. When original drummer John Rutsey left the band following their debut album, Neil Peart took over the drum throne, and the die was cast.

Thirty years later, a lot has changed, and recently there have been some serious bumps in the road. Peart lost his 19-year-old daughter in a car accident not long after finishing the tour for 1996's Test For Echo, and his wife died of cancer a year later. (Peart's novel, Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road, documents the 50,000-mile motorcycle trip he took to deal with his crisis.) Earlier this year, Lifeson was in the news after being charged with assault in Florida in connection with an alleged fracas at a New Year's party.

Yet, as he sits sipping mint tea and nibbling on a croissant in the Anthem Records office in downtown Toronto, Lee looks as if life couldn't be better for Rush, who are rehearsing for their first major US and European tour in eight years. "You know, surviving a difficult thing brings you very close," he says, referring to Peart's ordeal, "and I think we understand each other and feel unashamed to be overt about our understanding of each other now. It's made us much more respectful of each other's feelings; there's much more consideration for everybody involved.

"Alex and I probably have never been closer, and that's amazing after 30-odd years of hanging around with somebody," Lee says. "And the same is true of Neil. In all the difficulties they've gone through in their personal lives, we've been able to be there for each other as friends, and that puts you in good stead. I'm very fortunate to work with these guys."

SECRET TOUCH

One of the advantages of watching the live DVD Rush in Rio is being able to get a close look at your playing. Your right-hand technique is fairly insane.

Yeah, I developed kind of a goofy style. A friend says I'm the only flamenco bass player in rock. I just got into this weird way of manipulating the strings. I use my fingers in an up-and-down motion. I don't slap them up and down; I just play back and forth. My nails have gotten really hard, too, so I can get a much more rhythmic feel into what I'm doing without being all over the neck.

All of that is in aid of getting a bit more funk into my playing, to help the groove. It's kind of like the way a funk guitarist would use a pick, but I don't use a pick - I use my fingers like a pick.

Why don't you just slap and pop?

I could never get that down! [laughs] I used to watch my friend Jeff Berlin [fusion bass great with Zappa, Bill Bruford, Allan Holdsworth and others] do it. I remember telling him that I wanted to learn how to do that, and he said, "Don't! Don't learn it! It's destroying all bass players! Just play, man!"

Slapping tends to accent the drum kicks, but you don't have that traditional drum-and-bass relationship with Neil, particularly where his bass drum is concerned.

You mean bass drums! [laughs] Right. Well, we look at each other as a unit. We're in a hard rock trio that has a lot of solos, and our job during a guitar solo is to get really busy, so it doesn't sound empty when the rhythm guitar drops out. That concept is what created our relationship, and it goes back to Cream: when Eric Clapton soloed, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker went out. The guitar player is making a beautiful, melodic thing, and there are these other guys going mental in the background. So we felt our job was . . . well, to go mental in the background. [laughs]

We extended that from the solo into the main part of the song and developed a style where we pushed each other-not just in terms of being busier but also adding other influences: funk, Big Band-whatever we could soak up. Neil has always said the notes I play make his bass drum sound smoother, but I feel like it's the opposite-that his complexity makes it sound like I'm doing more than I actually am. The bottom line is that we make each other sound better, somehow.

We listen to each other, that's all. We listen, we understand each other's style and we try to accommodate. When musicians meet and jam for the first time, they're very attentive, right? We've tried to maintain that. Because if you jam with somebody you don't know, and you're not attentive, it's not really a jam. Then you're a guitar player! [laughs]

NATURAL SCIENCE

Lately you've been playing your old Fender Jazz Bass almost exclusively. Is it true you found it in a pawnshop?

Yeah, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. It was just one of those days off with nothing to do, and I went to a pawnshop. I was never one of those guys who went to pawnshops looking for instruments either. But this time I did, and there was a Jazz Bass hanging on the wall, with no case, cigarette burns on it, for $200 bucks. And it had a cool blonde neck-that's what really attracted me to it. So I bought it, and it's just the best bass. I'm really lucky.

Had you always been a J-Bass player?

No. The first bass I had was a Conora, a fantastic Japanese bass that Alex and I painted up in psychedelic colors like Clapton's old Gibson SG. But the first real bass I had was a Fender Precision. Then, in the early Seventies, I started following a lot of the prog bands, and I kept seeing these Rickenbacker basses - Chris Squire and Paul McCartney both played Ricks. So when we signed our first record deal, I bought a Rickenbacker 4001, and I used that for years, probably up until Moving Pictures. And even during Moving Pictures, I used that, but for half of Moving Pictures I also used the Jazz Bass.

I've used those two basses, the Jazz and the Ricky, for most of our recordings. Everyone has assumed it was my Ricky all the time, but actually I used the Jazz Bass quite a lot. "Tom Sawyer," for example; everyone thinks it's my Ricky, but it's the Jazz.

I was using Wal basses for a couple of years as well. I have a four-string and a five-string, and I used them all through Power Windows and Hold Your Fire. They have a snappier, funkier sound, particularly with the lighter-gauge strings, which aren't so "grunty" in the bottom end but more elastic.

After that I started looking for a different sound, because that wasn't satisfying the needs of the band at that time. Ever since the Counterparts record [1993], I've gone back to the Jazz and haven't budged. We worked with engineer Kevin Shirley on that album, who is really in love with analog sounds. He said, "Why don't you pull out your old Jazz?" So we plugged it into some Ampeg SVTs. It was a totally retro thing, I suppose, but I got hooked on the sound of it all over again. It's such a gorgeous instrument to play that it's now the only thing I think of playing.

NEW WORLD MAN

Why don't you use amps and cabinets onstage anymore?

Because I'm wearing in-ear monitors now. I have absolutely no need for speakers onstage; everything is coming through the PA, so it's not like the crowd is going to benefit from speakers onstage. Plus, now that we're all wearing in-ear monitors, the quality of sound and performance has just gone up about 300,000 percent. I think they've been the greatest innovation in live rock sound.

Is it like playing with headphones?

No, not at all actually. Look, if I play in front of a set of speakers, I do play more naturally. If I play with headphones in a room, I end up playing harder and I feel as if my fingers have less elasticity; I feel disconnected from the instrument. I mean, before a gig, when you're warming up, you think, Wow, I'm playing so smoothly, and then you get onstage and you don't play that smoothly because your muscles tighten up. Suddenly, you're in an audience environment, and there's all this volume - and as I said about playing with headphones: the more volume there is, the less connected I feel to the instrument. By using these in-ear monitors onstage, I can simulate a more direct connection to my brain, so I feel much more fluid, more intimate, with my bass. In the old days, with all those huge amps onstage, I always felt like my hands were big lamb chops.

So what was with the clothes dryers you had onstage last tour?

[laughs] It was a joke, obviously. It began because the bass gear that I use is so small it could literally fit in a backpack. So I talked to my bass tech, and said, "Well, Alex has this wall of amps. What do we do, put our device on a little chair?" Finally we came up with this idea: Wouldn't it be funny to have a couple of dryers onstage, spinning throughout the show?

So is there a Maytag endorsement in the offing?

I was hoping. [laughs] I haven't received any phone calls yet. It's not the kind of thing you can approach them about: "Hey, I'm a rock musician, and I use your dryers onstage..."

Power Windows: A Peek Inside Geddy Lee's Gear Truck

GEDDY LEE'S main and most cherished bass is the 1972 Fender Jazz he bought in a Kalamazoo, Michigan, pawnshop for $200 (see main story). What he likes best about it is its low end. "My particular Jazz Bass has more bottom than the average Jazz Bass," Lee says, "though I don't know why." It could be for several reasons. "I put a Badass bridge on it, tt says Lee, "so it doesn't have a stock Fender bridge. And it's got a very thin maple neck. It's made of alder wood, which Fender used for a short period of time, and it's a very hard wood. I also suspect there's a wiring problem, but I won't let them take it apart to find out because I don't want it changed."

As it happens, Lee's Jazz is the very bass on which the Geddy Lee Signature J-Bass is modeled. Says Lee. "I did an A/B test, and, okay, it doesn't sound exactly like mine, but it's pretty darn close. I was quite pleased."

For Rush's 30th anniversary tour, Lee will pack four additional J-Basses, mainly to accommodate different tunings (drop-D for a couple of songs, and a whole step down for "2112"). "Those are Custom Shop Jazz basses, circa 1996," says Russ Ryan, Lee's bass tech. All but one of the Custom Shop basses have been outfitted with Badass bridges, and all sport RotoSound Swing Bass 66 strings - gauges 0.105, 0.080, 0.065, and 0.045 - and are plugged into a Samson UR-5D wireless.

Instead of the typical backline, the stage behind Geddy features three front-loading Maytag dryers (set to Heavy, perhaps?). You see, Geddy runs his bass though a speakerless rig consisting of an Avalon U-5 tube DI, a Palmer PDI-05 speaker simulator and a Tech 21 SansAmp RBI preamp, a setup he uses live and in the studio, mixing the signals of all three units depending on his needs.

Ryan warms the tone another step with a Trace Elliot Quattrovalve amp. "I run the signal into the input of that amp, then run the speaker out back into the Palmer input. The audio guys take a direct XLR output." Speakers still play a part in Lee's chain: Ryan also sends the Trace signal into a Trace Elliot cabinet beneath the stage, "because if I don't, the amp will just blow." Onstage, Lee relies on Ultimate Ears in-ear monitors run through a Sennheiser wireless system.

Anyone who has seen Rush knows Lee stays busy with nonbass gear as well, including Yamaha and Roland keyboards and Korg MIDI foot pedals, which trigger samples and sounds stored in a pair of Roland 5080 samplers.

"They're used mainly to allow us to remain a three-piece live," says Lee. "It's so difficult, because I'm playing the bass part and simultaneously hitting these pedals to trigger extra bass parts, keyboard chords, or even looping guitar arpeggios. And I'm singing. It's a mental pretzel." -J.D.C.

Reverse Polarity

Geddy Lee looks back at a few Sixties classics covered on Rush's new EP, "Feedback"

- "Crossroads" Recorded by Cream

Wheels of Fire (1968)

Bassist: Jack Bruce - "Summertime Blues"

Recorded by Blue Cheer

Vincebus Eruptum (1968)

Bassist: Dickie Peterson - "7 And 7 Is"

Recorded by Love

Da Capo (1967)

Bassist: Ken Forssi - "The Seeker"

Recorded by the Who

Meaty Beaty Big and Bouncy (1971)

Bassist: John Entwistle - "Heart Full Of Soul"

Recorded by the Yardbirds

For Your Love (1965) [webmaster note: "Heart Full Of Soul" appears on "Having A Rave Up" (1965)]

Bassist: Paul Samwell-Smith

"It's a very simple version of the song, quite unlike anything else on Feedback. We just set up and played the song live; afterward, I did just a single track of vocals. When' we mixed it, we even set up the stereo field so that the guitar is off to on one'side and the bass is off on the other side."

"The song has been done by a lot of people, but the first version we all loved was by the Blue Cheer. In fact, we played a few Blue Cheer songs back in those days. They were our heroes because they were the loudest power trio in the history of power trios. We really dug that!"

"One of the weirdest songs ever written. Pure surrealism. Alex and I loved this song when we were kids, especially the chord progression. The lyric is probably the goofiest thing I've sung in my life, We had some fun with it, because it's lightning fast, and Neil plays one single snare roll from the beginning of the song right to the end."

"There were so many other Who songs that we wanted to do, but there was something about 'The Seeker' that we all liked, and I think it's because in our own songs we never play that slowly! We're always so hyper, and there's something about that song and that feel that's just so classic."

"We changed it up a little bit. The verses are very simple, and the choruses kind of kick in with a block of harmony that I wrote. I think it's one of the best things we've ever recorded. As soon as it comes on, it sounds contemporary, but it sounds like the Sixties, too. It feels like there should be an Austin Powers movie running with it simultaneously."