Rhythmic Explorer

Exclusive Interview with Neil Peart

By Owen Hopkin, Drummer, November 2004, transcribed by John Patuto

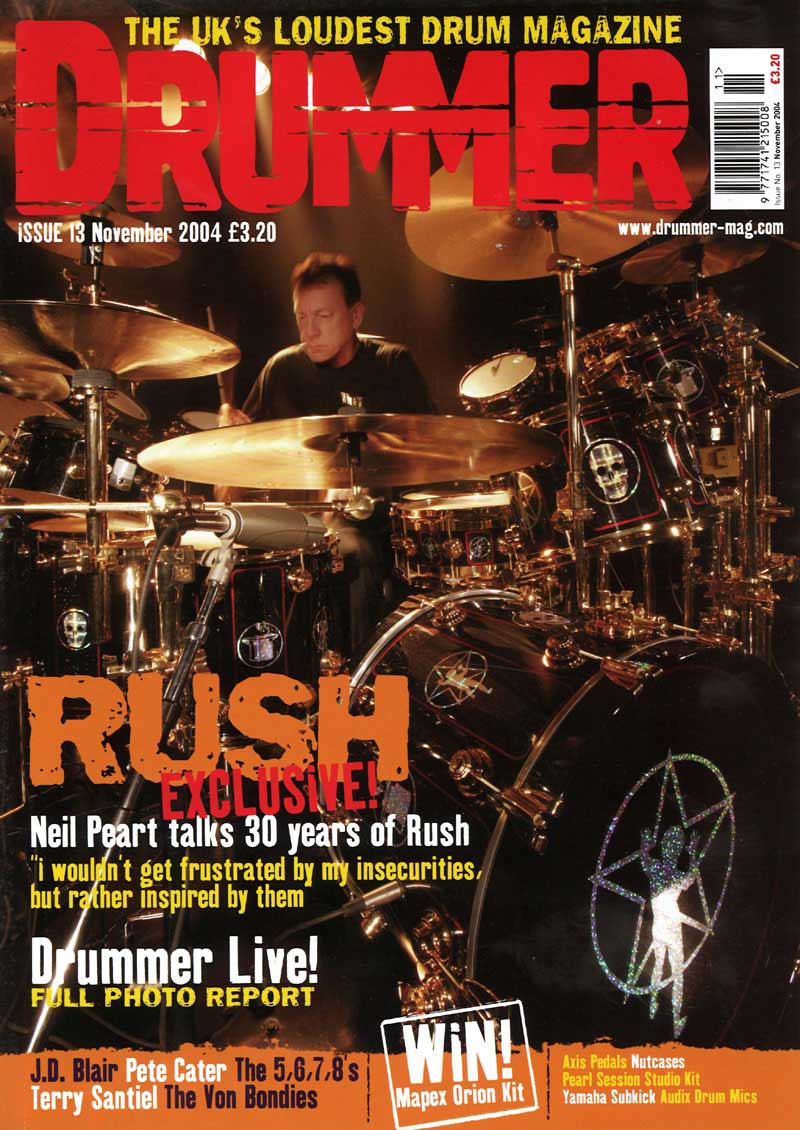

These days, 'legends' seem to come and go quicker than the turning tide. Neil Peart, over 30 years with Rush, has remained a vital and inspirational force behind the kit.

You can usually spot the people who've worked in the music industry for any great length of time: they cower in dark corners twitching nervously, constantly running their hands through thinning, grey hair and wax lyrical to no-one in particular about the dire state of modern music. In a business where cynicism seems to conquer even the purest of souls, the challenge of emerging unscathed is a feat comparable to mastering one-handed drum rolls - wearing a boxing glove.

Sitting in a dressing room backstage at Wembley Arena, Neil Peart is relaxed, amiable and perfectly courteous. Having notched up 30 years and 17 albums, driving Rush to new creative heights and consistently breaking fresh ground in rock drumming, you almost wouldn't blame him for being a little jaded by the trials and tribulations of the music industry. Over the course of an hour-long conversation, however, he talks enthusiastically about his childlike love of drums and of his continuingly fruitful, creative - and personal - relationship with his band-mates. At once deeply interesting and profoundly inspiring, it's a conversation as far from the cynical jabbering of old hacks as you can possibly get. It is, in short, the stuff of legend. A true drumming legend, no less.

In the beginning...

Neil Peart's dressing room is as homely as a clinical arena dressing room can be. It's his own personal room; band-mates Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson share a similar space down the corridor. A five-piece DW black and white sparkle sits in the middle, all set for Peart and his pre-show, freeform warm-up. A huge map of the UK hangs behind the kit's throne, a tool to plan his exploratory motorcycle journeys on days off.

The room is a testament to Peart's desire to exert a little control in an environment where it would be easy to shrug shoulders and go with the flow. In true Lloyd Grossman style, it's the room of someone that exudes determination and focus, two attributes that were in abundance as soon as he got his hands on his first kit.

"Oh yeah," he says with a huge smile, "as soon as I started I was obsessive about it. I'd come home and start practising and play along with the radio. They had to make me stop practising, not make me practice. It was an irresistible attraction, really. The movie, The Gene Krupa Story, was the thing that really got me excited about it, but any time I'd see a drummer on television it was like a visual fascination as well as a musical fascination."

"I had a teacher for the first couple of years. That gave me a grounding in sight reading and different styles. After that, I went my own way with the foundation that he'd given me, kind of knowing what I had to work on. The teaching aspect was really important. You can't start in a vacuum. It's like any subject you want to learn, you have to have some sense of what there is to know and what to work on. You can't just say, 'I'm going to work on it', you have to know which direction to go. You can't just say 'I think I'll play drums today!' Nothing happens that way."

With his jaw-dropping rhythmical work, it'd be easy to see the young Peart as a drumming wonderkid, a natural born [drum] filler. What's t surprising, then, is that doesn't seem to be the case at all.

"It was a day-by-day process of doing ma-ma da-da on a pillow and, like I said, learning to sight read. Also, just being open to all the different styles that were there in the early 60s helped a lot, too. There was still a lot going on in pop music and jazz music to be inspired by and aspire toward. I can remember at that age seeing Buddy Rich on television and having no idea what he was doing; it was so over my head. But it was still something like 'Wow, I'd like to understand that someday so that I can play it.'"

So did you ever reach a plateau of confidence where you thought you were breaking away from the pack or really hitting creative heights on the drums?

"It was years to build that kind of confidence," he says sincerely. "Early on in my development it was more about feeling intimidated by what there was to know and being painfully aware of my own flaws whether it was technique, time-keeping or whatever: At no time did I feel that I had achieved anything, it was always an ongoing progression. I would say it took literally 20 years to build the confidence to think I half knew what I was doing and then another ten years to feel like I'd got on top of it. Now, I feel as if I have much more control over the instrument in terms of controlling time, and then having enough technique to reproduce whatever I can think of. But those are hard-won achievements.

"The tools that you have to acquire to get to that stage take so long! To even get double-stroke rolls or paradiddles - they take years to get decent! And then there's learning how to apply them and to think creatively about where you can use them in suitable musical ways! And then, of course, there's the whole musical education; of learning to understand music and timekeeping as a musical function not a metronymic function.

"In terms of what you're saying, of gaining plateaus of confidence or whatever, those are, for me anyway, such a hard-won process of insecurity and, consequently, ambition. I wouldn't get frustrated by my insecurities, but rather inspired by them. If I went to see a great drummer, some people would go home and say 'I'll never play again!' I would go home and practice. I'd be so inspired by that. I think that still applies when I hear great music that I really like. It still makes me want to practice."

So how about tips for new drummers? Is there anything you can pass on?

"Getting a teacher is the first recommendation. You can't learn too much. I worked on samba for a long time just to learn Latin feels. I've never used it, but I understand it and I have fun with it. Timekeeping, too, no one can work too hard on that. Every drummer goes through the stage of playing a fill, getting excited and speeding up, or coming out of the fill and slowing down. Everyone goes through that and it gives you great insecurity - other musicians pick on you, producers pick on you. It's very undermining because you think, 'Well, the drummer's first job is to keep time and I can't keep time'. Something everyone should understand though is a) that everyone goes through that and b) it's correctable. It takes the effort to practice and practice until you realise how to play your fills so they won't speed up and until you get an innate sense of time."

And what of reaching the heights of success? Does it take a certain type of personality to succeed?

"Well, yeah, there's the luck of the draw in certain ways in terms of genetics and temperament. There are no other drummers in my family, but something seemed to come together that gave me the ambition and the ability to realise that ambition. It wasn't easy for me, I wouldn't say I was a natural talent, but I had enough ability to be able to work on it and get it. That's been a key part of it for me, having the will to want to practice every day, to work on things and to improve. Talent isn't enough, character isn't enough - it takes a combination of those and a certain sensibility and ability to get along with people."

Rewriting the book

As anyone lucky enough to catch Rush on their recent UK tour will tell you, Peart's fascination and love for the drums is clearly thriving. Powering Rush through a three-hour set - and we're not talking pub standards here - Peart seems to pour everything he has into each stroke and gentle nuance. Odd time signatures and complex ostinatos pepper his playing, eliciting barely a shrug or a furrowed brow.

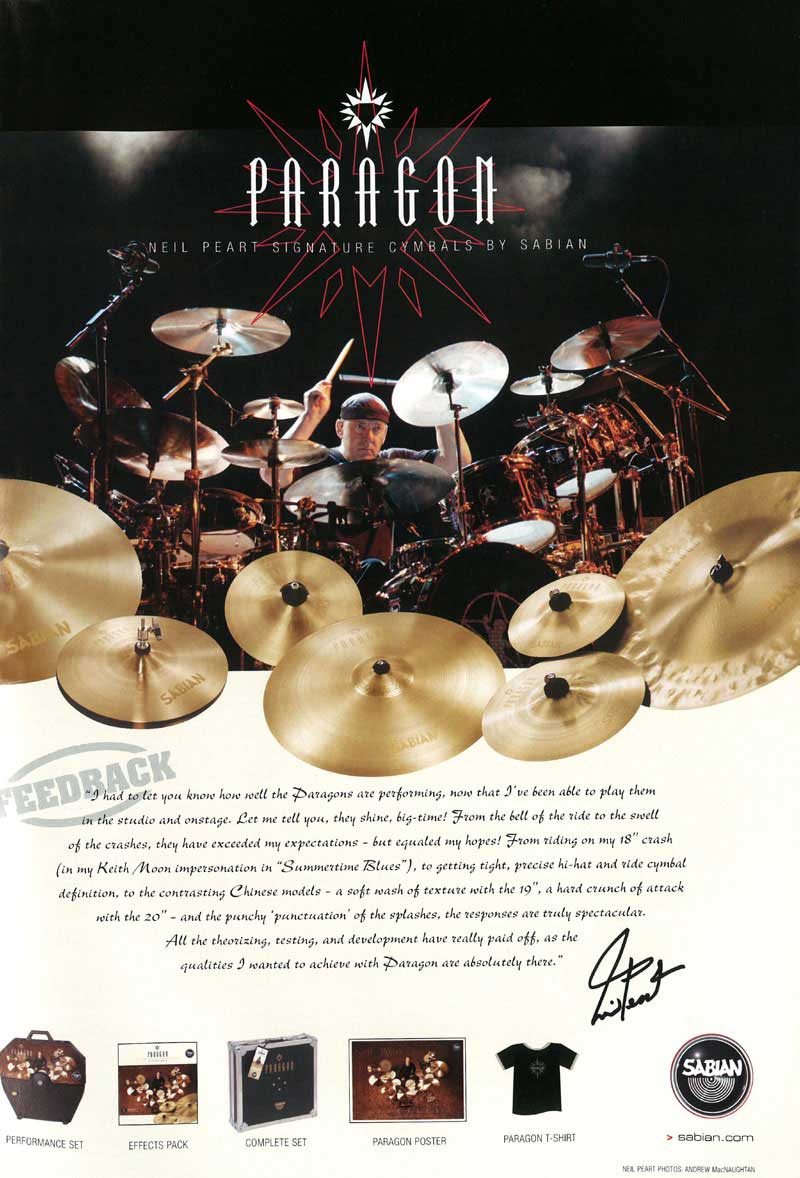

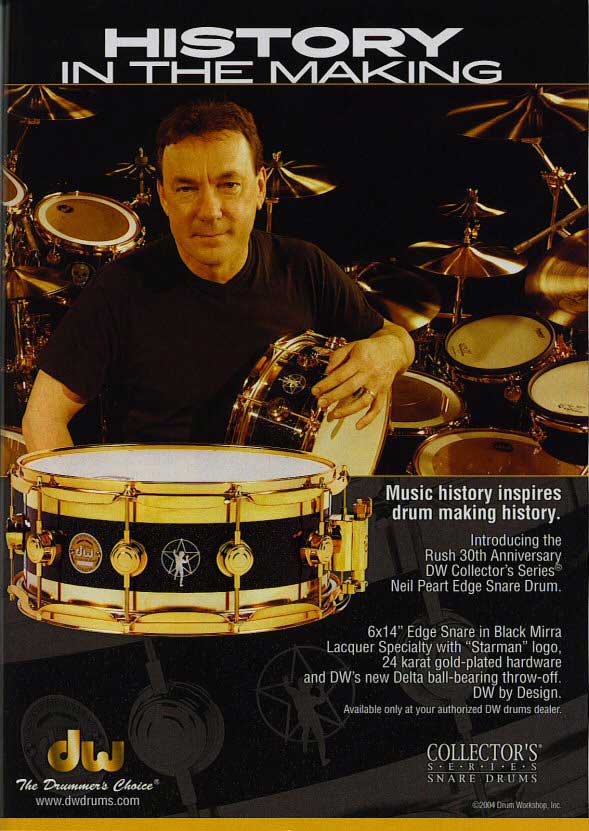

His enthusiasm, however, belies more than just a love of playing, it's clearly a deep love of the craft and of drums generally. Take one look at his Paragon range of cymbals or the hernia-inducing DW snare drum (it's seriously heavy) - as much love has gone into their making as each elaborately crafted Rush track.

"This year for me has been a tremendous example of that, what with working with Sabian in designing the Paragon cymbals," he says with all the childlike glee of a youngster that's facing his first kit on a Christmas morning. "It was the same with the drum kit I'm using, the 30th anniversary set. I went to the DW factory every week for a couple of months to design the drum set - what it would be like sonically, what it would be like visually. I was able to go there every week and consult with their craftsmen and work on it at that organic level, so that was cool.

"I still love drums, they're just as exciting for me to look at and think about as they were when I started. I noticed that last week, there was a drum set on the television, somewhere in the background, and my eyes just went to it. Just like they did when I was 12. Yeah, that fascination with the look of the drum set, that's very much alive."

His desire to keep pushing his own game forward is also alive and kicking. After 30 years of scaring drummers with his mastery of the kit it is, frankly, humbling to hear of his desire to keep learning and to keep improving. Perhaps most surprising of all was his decision, in the late 90s, to rip up his own rule book and start again with legendary teacher Freddie Gruber.

"It was more about getting out of the stiffness," he says. "In that period of modern music, where you're working with click tracks and sequencers, I suddenly got locked into this strict time. I adopted it and learned to keep metronymic time, but it began to feel that way, too. I began to feel stiff and restricted and I wasn't feeling in control of the time, rather the machine was in control of me. That was affecting my whole technique. I was getting stiff and I felt I'd done as well as I could with I the course of study and style that I'd built up until then.

"I really needed fresh fields. I knew I would go forward but I was trying to think which way to go forward I guess, and Freddie was absolutely the right person. With his history - he's in his seventies now, so he goes back to the 40s and 50s - he totally understands every aspect of drum set playing and every approach to playing it, so he got me back into a loose, dance-type approach to playing the instrument again. Suddenly I was just floating above the drum set. Now, when I work with click tracks, I can push and pull the time within the math. The math doesn't rule me, I feel like I rule it. I've learned to adapt, even in metronymic time, to have a lot of control within those milliseconds of time."

So what are you working on now? Judging by your voracious appetite for all-things drumming, there must be something keeping you busy?

"Well, I've had a huge breakthrough with the Drum Also Waltzes recently, which I use in my solo and in my warm-up routine. It's basically a 3/4 pattern with my feet. It comes from a famous drum solo by Max Roach but I saw Bill Bruford do it years ago and Steve Smith uses it, too. Waltz time is so difficult to do anything else on top of and at first I felt so stilted by it, but I kept working at it. Now, I can play 7/8 over the top of it, I can play 4/4 over the top of it, I can even play completely out of time with my hands and keep that 3/4 ostinato going. It's not particularly useful musically - I've basically learned a new trick - but it's a huge breakthrough in true independence. I now know I can do anything with my hands while my feet still play this waltz. Those are the kind of things I never get tired of. It's a great warmup, a great exercise and also - like rudiments - a ceaseless river of exploration."

The 'ceaseless river of exploration' could also apply to his band, too. Over the course of 17 albums, Peart has practically redefined rock drumming, pulling it in hitherto unimaginable new directions. At no point has the 'easy option ' ever seemed like a realistic choice for Rush, who've consistently pushed themselves to greater artistic heights. But what goes into creating one of Peart's elaborate drum tracks? Unsurprisingly, it's a lot of blood, sweat and tears.

"The way we work as a band is I work on the lyrics while Geddy and Alex work on the musical ideas," he says. "They create a work tape and then when they're done for the day I'll go in and just play along to the work tape. I'll try to work out what suits the song best and what the song seems to want rhythmically and dynamically. Then, I just really like to play it over and over again, just refining it down."

"The last record Vapour Trails was done pretty much spontaneously. I'd played the songs over and over enough to know what worked, but I hadn't nailed down definitive parts - every time I would play a song through it would come out a little different. I kind of evolved that out of loving to be prepared but not liking to be overworked and having parts sound too learned. I do have a tendency to over prepare and have every beat worked out and, of course, that can get stale and take the freshness out of it. Again, I also really wanted to avoid the stiffness factor that I started feeling in the early 90s."

As one of Rush's finest albums in years, Vapour Trails is a drumming wonder from start to finish. It's a testament to the trio's working relationship and of their determination to keep things fresh creatively. In an age where bands seem to form and break-up over the course of a rehearsal session, it's refreshing to see a musical hunger stretching into its third decade.

"We never get bored of each other. Honestly," he says fondly. "We do know each other very well, but we always change - we all have such broad interests. It's the same artistically, too. We do know each other so well but yet we're different from each other and have different temperaments, which is most important. Geddy and I like to work quite methodically on our different things, where Alex is very spontaneous and very emotional about what he does. That's the perfect balance! Geddy and I will like to tinker and get things organised, whereas Alex will just come in and have a wonderful idea that will come out of his soul. That's inspiring to us and we create a framework to allow him to do that. It's the same on stage and you can see that every night."

Trading places

As sound check time approaches and management storm the dressing room to wind up our conversation, Drummer sneaks in one final question: Would the Canadian ubersticksman have traded 30 years of steady, consistent success for five years of zeitgeist-throttling, super-fame? Peart, unsurprisingly, is having none of it.

"No contest," he says emphatically. "I've seen people torn apart by that. We've been lucky because our success came gradually. We've been able to adapt because, let's face it, this isn't a natural way to live. And if you get into the complete limelight of having that kind of 'number one band in the world' situation few people survive that unscathed and nobody survives it unchanged. I'd rather be able to work when I want to and be able to do these other things - the books, the motorcycling - in tune with everything else and feel fulfilled.

"Life can be very empty if you don't have a mission or if you don't have something you want to do. Last year, when we took time off, I wrote a book. It gave me something to do every day, an ambition, a satisfaction. Creatively, I felt I was building something and I think life would be empty without that. It was never about earning enough money to retire or, as Beyonce said, having enough money and then starting a family. That's not an artist. That's not how it works at all. As an artist you have a desire to express yourself and to explore - that doesn't stop. I've commented in my latest book that some bands' fashion changes and suddenly they have no work anymore; no one wants to hear them. How hard must that be! That's where I feel fortunate that we've managed to keep an audience with us. You can't just choose to be popular, that's outside your control. You can make your best guess of what it takes, and for us it was like, 'OK, we'll be as sincere as we can and play the music we love and hope that other people will love it too'. There's no doubt we've been incredibly lucky and I feel very fortunate for it."

The Song

"'Tom Sawyer'. I play it every night, I've played it thousands of times, but I'll never get tired of it. It's never easy and it's always a challenge to play well every night. There's a central root - call it a groove or pocket - in that song that just has to be nailed. You can't just play the part, it has to feel right, too. Part of the song's sound is the sheer force of it, so for that alone I have to give it my conviction, all of my strength and all of my mental application to execute the parts properly."

The album

"We didn't know it at the time, but Moving Pictures was certainly the album I'd consider Rush's first record. We did a lot of work before it, a lot of experimenting, but we really got cohesive and found our stride on that. By then, we knew what worked for us and we'd really started to learn a lot more about song writing and arranging. I think there is a linear aspect to developing as a band, but I think there's also an accidental thing where different factors just happen to come together at a certain time. Moving Pictures was definitely one of those."

The Kit

When we were working on the design for the kit, and because it was the anniversary tour, I wanted to use different logos from our different albums. Keith Moon had a drum set from the 60s called the Pictures Of Lilly set that was black and had rectangular designs on it. When I was a kid that was my dream set of drums and part of the theme of these drums was they would be my dream drums. I wanted them to represent me at all ages, so I kind of reflected back on that. My favourite colour combination is black and red, so I wanted to take that and add in the different logos. It's an incredible kit.

GEAR-BOX

Drums: DW Rush 30th Anniversary set

22 x 16" bass drum

14 x 5.5" Collector's Series solid snare for indoor arenas

14 x 6" Edge snare for outdoor venues

13 x 4" snare

15 x 13" rack tom

8 x 7" rack tom

10 x 7" rack tom

12 x 8" rack tom

13 x 9" rack tom

15 x 12" floor tom

16 x 16" floor tom

18 x l6" floor tom

Hardware: All DW

Cymbals: Sabian Paragon Series

13" hi-hats

10" splash

20" crash

16" crash

8" splash [top)

14" hi-hat [bottom)

18" crash

19" & 20" chinas

Electronics:

malletKAT

Dauz Pad

V-Drum Pad [set inside a DW shell)

V-Drum Cymbal Pad

V-Drum Hi-Hat Pad

V-Drum Bass Drum Pad [set inside DW shell)

Shark Trigger Pedal

Rack:

Roland TD-10 Brain w/Expansion Card

Emu 5000 Samplers

Percussion:Cowbells

Heads: Remo

Sticks: Pro-Mark 747 Neil Peart model

Review: DW Neil Peart Snare

By Ian Croft

BIG MONEY: Over thirty years of playing snare drums gives Neil Peart more than just an edge when it comes to knowing what he wants a snare drum to be.

Sat before me is one of the most gorgeous snare drums I have ever had the privilege to hold and review. Weighing in at a massive 10 kilos, the drum is beyond eye catching. Couple the fact that Neil Peart has had more than an awesome career sat behind a snare drum and then add DW's impressive ability to produce some serious sounding drums, and you therefore have something fast approaching perfection.

Construction

Personally designed by Neil in conjunction with DW's drum artisans, this drum features a ten-ply maple shell with heavy-gauge brass band bearing edges, producing a combination of wood and metal in its sound characteristic. That to you and me adds up to a schizophrenic-sounding drum that enters into both metal and wood worlds. The brass edges produce the high-end crack, with the warmth factor kicking in from the wood shell, making this drum one versatile little monster. DW have seamlessly fitted the brass edges and wood shell together in a magical manner, and by adding the visually stunning 24-carat gold-plated hardware and hoops, it only remains for the Black Mirra Lacquer Specialty finish to truly take your eyes out! Added into the outer shell finish is the Rush 'Starman' logo, making for a totally dazzling look.

The snare release features DW's new Delta ball bearing throw-off. This throw-off is seriously heavy duty and benefits from a ratchet system that can be adjusted by finger, or very neatly, with a drum key. The ratchet teeth prevent the snare wires from slackening off during any excessively heavy playing and is a common sense feature that perhaps other manufacturers will pick up on and make as standard, such is its efficiency. The snare-release mechanism operation is very smooth, with the throw-off lever sited to the right-hand side of the unit. There is a very reassuring 'click' as the release lever re-engages into its final locked position.

The opposing snare butt is another fine example of engineering and design and clamps the snare cord or straps, with enough grip to prevent pull-through. Both the snare chord/strap restrainers are locked into place by use of your drum key. So, no need to go searching for a screwdriver mid-gig.

Each and every metal piece that sits upon the outer shell has a rubber gasket behind it, preventing any damage to the shell's magnificent sparkle finish. The drum features ten lugs top and bottom, making it easy to tune this instrument to a fine level. Plus, the fitted DW head even goes so far as to tell you in which manner and order to tune the head.

A 20-strand 'True Tone' set of brass snare wires straddle the bottom snare head and sit beautifully across the bearing edges and into their snare beds. The heavy-gauge brass bearing edges are machine cut to an immaculate level, as you would expect, and internally, each screw supporting the nut boxes is equipped with extra spring washers behind the domed screws for added security. Seems that nothing has been overlooked, or left to chance.

Sound

The 14 x 6" shell offers the combination of wood and metal, as stated previously. Tuning the drum up from a low dull thwack to a window-shattering crack is simple as ABC! The ten lugs offer an abundance of tuning options and when you add in the incredible sensitivity of the drum, you are sitting behind something close to perfection. Buzz rolls and double strokes absolutely sing from the far edge to the very centre of the drum, effortlessly reproducing the beats that you throw down.

What is really interesting is the combination of sounds that can be found between the outer bearing edge and the centre of the drum. The outer edge, due to its proximity to the brass bearing edge, produces some interesting highly end ring, whilst the centre of the drum relays a fat, beefy back beat. Moving beat 2 to the outer edge and then playing beat 4 in the centre gave the impression that two snare drums were being employed. Drop the snare release off and the drum enters into Latin territory with its timbale vibe. Spectacular.

After fitting one of Remo's Emperor X batter heads, the drum still retained a good level of high end, although such a heavy two-ply head did not really allow the drum to speak in the fashion for which it was designed.

Conclusion

The Neil Peart Signature snare drum is certainly not a cheap option when considering snare drum purchases in general. Nevertheless, this magnificent piece of craftsmanship would serve you well in most musical areas and not just in a rock vein. DW's craftsmen and Peart's obvious delight at being able to design a snare drum have resulted in a near-perfect drum. As part of DW's 'Drummers Choice' range, whereby you can order the same snare drum as used by your favourite drummer, which is proving a real winner for the company, Neil's snare will undoubtedly become a keen seller and not just amongst Rush aficionados. This drum could also be considered as an investment as anything that is this 'exotic' will quickly attain certain memorabilia status.

The level of manufacturing craftsmanship is right up there amongst the very best that we have seen here in the Drummer office, and with DW's status as drum builders, this drum will only boost that image even further.