Dropping Everything

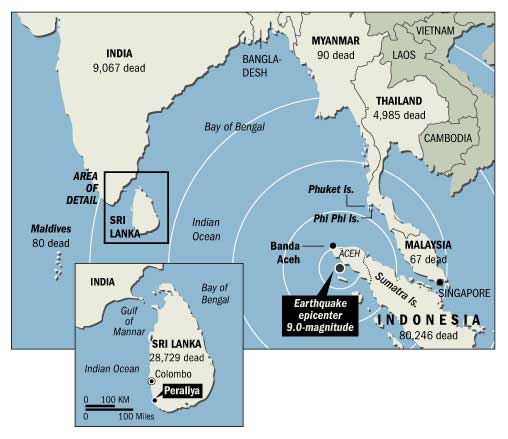

By Patrick Barta, Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2005

click to enlarge

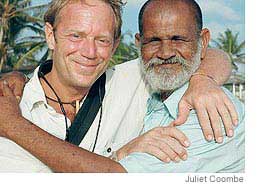

Bruce French, sometime-cook for Pearl Jam, with Aiyypyge Darmadasa, unofficial leader of Peraliya.

After a local band's instruments were destroyed by the waves, the rock group Rush, friends of Mr. French, donated new equipment.

When the tsunami hit, bruce french rushed to pitch in. His five-month journey was an unexpected crash course in charity, big corporations and the price of trying to help.

On Dec. 26, Bruce French, an itinerant private chef living in a teepee, was kicking back in Telluride, Colo. He had a few simple resolutions for the New Year. Find a new girlfriend and ski the Telluride powder until it melted away. After that, he planned to put in a few months on the road cooking for his pals in the rock band Pearl Jam. Then he'd return home for some well-deserved Bruce time.

It would be like any other year for Mr. French, who at 45 was divorced, childless and free of major commitments.

As he pondered his next move, a tsunami on the other side of the world was tearing the seaside fishing village of Peraliya, Sri Lanka, from the map. On a friend's TV, Mr. French watched the horrifying images that would grip viewers everywhere, and something flipped a switch. He had felt a kinship with Sri Lanka ever since he toured the country on a motorcycle several years before. He didn't have to work the next day, or the one after that. Why not go help?

Before Mr. French knew what he was doing, he was on the phone, scrambling to get to Colombo, the island nation's capital. Through friends, he made contact with a New York filmmaker planning a similar expedition and agreed to join forces. He cashed in some frequent-flier miles and said goodbye to "Two-Dogs" Kevin and his other buddies in Telluride. After a giant dinner of sushi and curry, he set off.

Mr. French made his five-month journey in close quarters with a handful of other impulsive volunteers. It turned out to be an incalculable stroke of luck for Peraliya, a speck on the map that might well have fallen through the cracks of the world's thinly stretched disaster response.

Working with a donated laptop in a tool shed, Mr. French would find talents he never knew he had. He became a village engineer, lobbyist, quartermaster, and behind-the-scenes power broker and trauma counselor. When locals needed mosquito nets, antibiotics or body bags, they didn't go to the Sri Lankan government or the Red Cross. They went to Mr. French and his companions, who alone seemed to get things done.

A similar impulse to help now grips many in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. As Mr. French's experience shows, billions in aid dollars are scant use without people on the ground with entrepreneurial instincts and unencumbered by bureaucracies. His experience also suggests that while such intense, personal efforts can bring great satisfaction, they're often accompanied by both risk and pain.

Mr. French confronted and rejected the kinds of notions many people harbor in times of crisis: The international aid community would never let down a person in need. The poor are always noble. Big companies, including Big Oil, don't have a heart.

Over time, some locals came to resent the foreigners, who they thought were meddling in village affairs. Mr. French was forced to deliver aid in secret to forestall jealousies. One of Mr. French's friends began to drink heavily after long days of collecting bodies. Another came to view the Sri Lankans as ungrateful.

"The looks of despair and frustration gnaw at me," Mr. French wrote one night in his diary, after rains flooded two dozen temporary homes in the village. "I'm doing everything I can, but it's just not enough."

In the predawn hours of Jan. 8, Mr. French found himself wandering the halls of the chaotic Colombo airport. He later met up with two volunteers he had contacted through his friend in Colorado. The pair had already joined forces with a fourth would-be volunteer they met at the baggage carousel.

Armed with a few thousand dollars to pay their way, they rented a van and found some supplies. Loaded down with food and medicine, the foursome - which included a former army engineer and the director of a movie about a mobster who smokes marijuana - headed south along the battered Sri Lankan coast.

What they saw shocked them: town after town reduced to rubble. At one village, their van was swarmed by starving families. They also saw their first dead body - a headless, limbless torso - and began to wonder what they were in for.

Based on a recommendation from a couple of volunteers they met on the way, the group decided to stop off in Peraliya, a town of 500 or so families sandwiched between train tracks and the beach. Ordinarily, Peraliya was just another fishing village, with dirt roads, tall coconut trees and a steady supply of arrack, the local liquor.

But in the days after the tsunami, it was one of the most famous towns in Sri Lanka. It was here that the giant waves derailed a packed passenger train, the "Queen of the Sea," killing almost everyone on board. That made it a magnet for volunteers.

When Mr. French showed up with his crew, they found scenes now familiar from television: Steel bars that once reinforced concrete jutting into the air; goats rummaging through the rubble; ripped garments hanging from the branches. Out of about 1,500 residents, almost one in seven was dead. Some buildings still stood, especially those farther from the shore, but many other homes had been reduced to their foundations. Peraliya was among the hardest hit of the towns on Sri Lanka's southern coastline.

What the group didn't find was any formal authority running a concerted relief effort. Peraliya is too small to have its own government and relied on nearby cities for police and administrators. Aid organizations had their hands full elsewhere and couldn't give their full attention to every town. The survivors were dazed and for the most part hadn't lifted a shovel other than to help create two mass graves near the water.

While the tsunami triggered one of the biggest fund-raising efforts in world history, the aid was taking a long time to reach outlying areas. The World Bank, for example, made some $150 million available to Sri Lanka for reconstruction, but so far only about $35 million has been disbursed. Relief agencies worried about moving too quickly in case survivors built on land with poor drainage or without proper legal claims. Some took extra time to put in place accounting procedures to prevent graft.

Meanwhile, the Sri Lankan government struggled with the enormity of the problem. Early on, it prohibited victims from rebuilding close to the water, a decision that delayed reconstruction efforts. The government's decades-old conflict with Tamil rebels also complicated matters. Some aid workers say the government sometimes impounded supplies for fear they could be delivered to insurgents.

Mr. French and his friends decided to start working until someone told them to stop. No one did. Foreigners rarely visited Peraliya before the tsunami, and the locals were either too surprised by their presence - or too shy - to tell them to leave.

More importantly, the group had water, antibiotics and a smattering of medical training, all of which the town needed desperately. Using hand signals and gestures, Mr. French and the others quickly fell in with the town's most influential residents, who saw them as a lifeline to the outside world's bounty.

It helped that Mr. French was a practicing Buddhist in a predominantly Buddhist country. He carried his own prayer flags, totems that Buddhists believe bring fortune and good luck. He later presented the town's head monk with a gift of Utah desert sage, which he had bought with him on the trip. The monk allowed him to hang his prayer flags by the local temple.

When Mr. French and the others began picking up rubble, Aiyypyge Darmadasa, a local fisherman and one of Peraliya's most influential residents, joined in, conferring legitimacy on the outsiders. Mr. Darmadasa was famous in town for being carted off in a sack by government goons in the late 1980s when he supported a local opposition party. He also owned several fishing boats.

Before the foreigners arrived, Mr. Darmadasa says, the village's patchy efforts to establish order had become bogged down in arguments over whose house should be rebuilt first. "We don't know how they all came here," Mr. Darmadasa says, but after they did, "things started to change and slowly we started to build things."

Mr. French and his colleagues first cleared debris from the school library, where the waves had lodged books in the rafters, and converted it into a field hospital. Locals previously relied on a clinic near Hikkaduwa, a nearby tourists town, and a hospital in Galle, Sri Lanka's fourth-largest city, about 14 miles away.

The foreigners hung out a donations pail to collect money from gawkers, both Western tourists and locals, who had come to see the train. The passenger cars had been scattered around the village, then recovered and put back on the tracks. The volunteers also helped recover rotting bodies from the mud behind the temple.

The four volunteers met a young, English-speaking villager who once lived overseas and had lost her home. They persuaded her to work as their translator and offered her space to sleep in the new field hospital.

All day long, trucks loaded with aid thundered down the coast road. Mr. French's crew employed guerrilla tactics to flag them down. Brandishing walkie-talkies so they'd look like official aid workers, they persuaded one delivery truck from Colombo to stop and hand over bags of rice and dahl, a basic foodstuff similar to lentils.

"We've just been blown away by how much [aid] could drive by" on the way to somewhere else, Mr. French reflected while sitting on a windowsill of the medical clinic one January afternoon.

Such boldness endeared the foreigners to the locals, who were quickly growing frustrated with the Sri Lankan government's lack of leadership. There is "just planning and planning and no working," said D.M.G.I.S. Dharmapala, a 21-year-old machinist who grabbed onto a floating roof when the waves hit.

As the foreigners cemented their place in town, they awarded themselves titles to clarify their roles and even wore badges. Mr. French became Head of Logistics. Oscar Gubernati, an Italian filmmaker who lived in New York, said he wanted to be CEO. "I don't care what you call yourself," Mr. French recalls joking. "You can be the King of Sri Lanka for all I care."

The foreigners helped form committees of villagers to carry out projects. One local was put in charge of finance. Another was deputized to handle fishing equipment.

In his diary soon after his arrival, Mr. French recorded his first impressions. "The stench of death is thick," he wrote. But for the most part the mood was good: "So much is coming together."

As a young man, Mr. French had no idea what he wanted to do. When he was in high school in Kentucky, his stepfather, a marine, thought it would be a good idea for him to join the military. Then he was caught with a quarter of a pound of marijuana in his locker and that idea evaporated.

Before leaving school, Mr. French got a job washing dishes at a country club, where a chef took him under his wing. That led to various cooking gigs including work as a caterer to traveling rock stars. Mr. French eventually wound up in Cincinnati, where he opened his own restaurant, Bistro on Vine. He married on Halloween 1987 and renovated a Victorian home.

But all that wasn't making Mr. French happy. In 1991, he took a six-month sabbatical to hike the Appalachian Trail and came to the conclusion he'd been working too hard. When he returned, he sold the restaurant and decided to leave Cincinnati. His wife, then a pharmacology student, wanted to stay. They split.

Out skiing one day soon after his sabbatical, Mr. French found himself in the lift line with a wealthy sailboat owner, the late Jerry Wernke, owner of a tool-and-die company. As they were carried to the top of the mountain, the two men discussed Mr. French's working for Mr. Wernke on a sailing trip.

The next day, Mr. French agreed to take a job cooking and taking care of provisions. Over the next several years, and with other employers, he stopped in Gibraltar, Sudan, Tahiti, and Djibouti. He partied all night on the beaches of Thailand.

He also landed in Sri Lanka, where he rented a motorcycle and cruised the winding mountain roads. He visited Buddhist temples and camped near a turtle hatchery, chasing away dogs to protect the eggs.

"It was a magical time for me. I knew I was going to come back," Mr. French said later.

When Mr. French returned to the U.S., after a 21-month absence, he wound up in Telluride, where his cousin was opening a restaurant. He settled into a life of skiing, cooking and touring with rock bands. He drove a pickup and slept in a teepee on a mesa 30 minutes outside of town. He relied on a wood stove for heat. He showered at a friend's place.

"There's not a manual for such a life," he says.

Mr. French's makeshift existence prepared him well for post-tsunami Peraliya. Soon after his arrival, he bought a cheap motorcycle and took up residence in a $5-a-night surfer hangout in Hikkaduwa, which was in better shape than Peraliya. He had a small concrete room on the second floor overlooking the ocean. Among his gear: a Frisbee, candles and a well-worn copy of "Desert Solitaire," an ode to the American West by the radical environmentalist writer Edward Abbey.

As the weeks passed, Mr. French's relaxed demeanor made him one of the leaders of an informal network of freelance aid workers, which on any given day could total 30 or more people. Some stopped by to see the train and stayed. Others had tried to land work with international aid agencies but had been rebuffed. Volunteers included a French surgeon, a German paramedic and a retired man in his 60s who showed up after completing a stint on Ireland's version of the reality-TV show "Survivor."

At night, many of the volunteers decamped to their ramshackle guesthouses in Hikkaduwa and over fried rice recounted war stories of decomposing bodies and hospital trauma. To take the edge off, they drank beer and occasionally smoked the local marijuana.

The idea that they were effectively running a town thousands of miles from home "was hard to believe," Mr. French said one April afternoon, taking a break on the balcony of his guesthouse overlooking a calm ocean. "It's not often in life that you have the opportunity to rebuild a village, to build a community."

Mr. French quickly discovered he had a special talent for relief work. Through his past jobs, he was an expert in solving logistical problems, such as finding cooking ingredients in unfamiliar cities while on tour and locating supplies in foreign bazaars.

With the help of a volunteer who worked in the oil industry in London, Mr. French scored a free laptop from Royal Dutch Shell PLC. The volunteer, who worked for Exxon Mobil Corp., gave him other contacts who helped assess the storm's environmental impact. For example, the waves pulled a lot of soil into the ocean, lowering parts of the village by a foot or more, which in turn made it more vulnerable to flooding.

The aid meant a lot to Mr. French, who had held oil companies in low regard. It "restored my faith that when something bad happens, the world comes together," Mr. French said. "Even the big guys you despise can do some good stuff."

Mr. French also began to shake the trees for cash. For weeks, he pressed officials from the Colombo office of Deutsche Bank AG - who had heard of Mr. French through the German embassy - to divert some of their tsunami aid to repair Peraliya's drainage system. Although the bank didn't ultimately fund that project, it says it committed to pay about one third of the $500,000 cost of a new medical center.

Villagers began to realize it made most sense to go to Mr. French and the others with their problems. On one steamy February afternoon, a villager casually mentioned that his son wanted a bicycle because he couldn't afford the bus to school. The next day, Mr. French showed up with a beaten-up but usable bike. When Mr. French found out some local musicians had lost their instruments in the tsunami, he contacted his friends in the Canadian rock band Rush, who donated several thousand dollars for guitars.

Although Mr. French "has a little bit of the hippie in him," he is "definitely a take-control kind of guy," says Alex Lifeson, the band's 52-year-old guitarist.

Mr. French became an informal spokesman for the village when VIPs stopped by to view the train, which by now had been dragged and abandoned a few feet from the tracks by the Sri Lankan government. Visitors included former Bill Clinton aide Erskine Bowles and Hunter "Patch" Adams, an American doctor whose life was made into a 1998 movie starring Robin Williams. When possible, Mr. French and the others used these visits to snag more aid.

One willing listener was Jeyaraj Fernandopulle, Sri Lanka's Minister of Trade, Commerce and Consumer Affairs, one of the few government officials Mr. French believed was sincere about wanting to help. Over the next several months, the minister made 31 trips to the village. He pulled strings to get the volunteers' visas renewed and put a van at their disposal. His visible backing gave Mr. French and the others another official seal of approval.

"Their presence was essential" in Peraliya, Mr. Fernandopulle said in a recent interview.

Mr. French made newcomers feel like more than tourists. Some volunteers began calling him the "The Zen Master" because he never seemed to get angry or flustered.

"The first thing I noticed was that there was a buzz about the place," said Aaron Taylor, an ABC Sports commentator who played offensive lineman on the 1996 Green Bay Packers Super Bowl team. Mr. Taylor had a New Zealand vacation planned for early 2005 but diverted to Sri Lanka to help out. "It all indirectly goes back to Bruce," he says.

Soon, the strain of seven-day work weeks began to build.

"We have fallen into a brain freeze," Mr. French wrote in his diary one night more than a month after he had arrived. His energy was sapped by a series of misadventures. One afternoon, a deranged local man ran through town screaming that another tsunami was coming.

The volunteers were finding bodies at a dizzying pace. On one particularly bad day, 16 were uncovered. Workers found bodies with hands cut off by thieves out to steal rings. Another day, Mr. French and another man moving earth with a backhoe came across a corpse. The laborer used a crowbar to let air out of the bloated body.

"I cried that night," Mr. French says.

One of the original four volunteers, Donny Paterson, a former Australian army engineer, was starting to crack. He played a key role in coordinating aid but was also drinking a lot of arrack and not sleeping well. One day, he came across a tuk-tuk - a three-wheeled motorized taxi - upended in the road. No one was helping the driver, who was bleeding from the mouth. Mr. Paterson pounded frantically on the man's chest, to no avail. Watching the man die sent him over the edge.

"The big guy melted like an ice cube on a sweltering day," Mr. French wrote in his diary. Mr. Paterson returned to Australia, but had trouble adjusting, and came back to Peraliya soon after. He missed the camaraderie and the respect he commanded.

"I walk around [Peraliya] and people would say, 'G'day, Donny,'" he said after his return. "At home, I walk around, and nobody says anything."

Always a rough town, Peraliya began to revert to its lawless ways as the frustrations of living in a post-tsunami world sank in. Several locals attempted suicide and the clinic began treating stabbings and beatings. Donated goods began disappearing, including two generators as well as tents and mobile phones.

Resentment toward the foreigners was also beginning to emerge. Their presence had altered the village's dynamic, creating a new class of winners and losers.

A common complaint revolved around mosquito nets. Some villagers said they were unevenly distributed. As early as February, whispers filtered through the village that Mr. Darmadasa took bags of rice or other supplies to distribute among his friends and family. No one could provide evidence and both Mr. French and influential local monks say it didn't happen.

For his part, Mr. Darmadasa bats down the rumors: "Some people think I'm guilty of things because I'm close to [the Westerners], but not at all."

Chamila Priyanthi, the villager tapped as translator, also became disenchanted with some members of the volunteer group. Ms. Priyanthi accused Mr. Gubernati, the Italian filmmaker, and his girlfriend, Alison Thompson, an Australian-American filmmaker and nurse, of funneling money to "thieves" and other "bad" people.

Many of the complaints festered outside the medical clinic where women congregated each day to gossip.

"One day...the truth will come out," villager Ninirosh Nilmini announced after hanging out in the circle one day in April. The foreigners "aren't helping us, so why should they stay here," said another local from the front door of a temporary home built by foreign volunteers.

The disaffection upset some of the volunteers, especially Ms. Thompson, who began to see some of the villagers as ungrateful. "I have given my heart, my soul and every cent I own to these people," Ms. Thompson wrote in a posting on a Web site tracking the reconstruction, http://www.peraliya.com. "This trip has left me confused about mankind and how kind and how cruel we can be" to each other. She mused in a later email that perhaps some of the villagers "are just plain evil, and that is why the tsunami came here."

The strains made it harder for Mr. French and the others to operate. The town recorder said 34 Peraliya residents owned boats before the tsunami. When the volunteer group asked who needed new vessels, 56 people stepped forward. Sorting out the discrepancy led to "much screaming and infighting," Mr. French recalls.

One of Mr. French's projects was to help locals get new jobs. Sometimes, that involved locating equipment he would buy with his own cash and other contributions and then donate. To prevent jealousies, Mr. French began delivering the equipment at night.

"You have to do everything stealthy, behind people's backs," Mr. French said one day from the tool shed in the center of town. In one case, he says he told the recipient of a brick-making machine: "If it comes out that this came from me, I will deny it."

Because the villagers disliked open confrontation, complaints were largely communicated via whispers and hostile glances. But one day in March, tensions bubbled over.

Mr. French had just spent two hours walking the village with Mr. Bowles, the former Clinton aide, who had been named a United Nations envoy to assess tsunami damage. With some other UN staffers, they retired to an area outside the medical clinic where they sat at rickety school desks, a tarp shielding them from the sun. A number of locals gathered to watch.

Without warning, recall Mr. French and Ms. Thompson, a man they had never seen before emerged from the crowd. He announced that the villagers wanted the foreigners out and that he spoke for the entire community. Ms. Thompson and Mr. Gubernati angrily demanded to know who he was.

A UN mediator stepped in with a few words about how everyone was under a lot of strain. A few days later the man disappeared but his outburst left a lasting impression. In a recent interview, Mr. Bowles says he wasn't surprised by the expression of frustration: "People are always exceedingly grateful for help at first but after some point in time they want their lives back."

Soon after, the foreigners convened a town meeting in the courtyard by the medical clinic, a building local school leaders were growing impatient to reclaim.

About 75 villagers gathered in the dirt clearing, recall Mr. French and Ms. Thompson. The foreigners, sitting on a podium alongside Mr. Darmadasa, explained their activities, including where the money was coming from and how they were allocating it. The audience asked some questions but didn't say much.

After a while, Mr. Gubernati, the Italian film-maker, stood up and asked for anyone who wanted the foreigners out to raise their hands. No one did.

As April wore on, projects started to bog down, partly because of delays in getting donors to part with their money. One hitch: Mr. French wasn't a certified charity, which meant donors couldn't make tax-deductible contributions. In one case, it took a Telluride group, which had raised $15,000, three months to work around the problem.

Meanwhile, the monsoon season was approaching. Mr. French knew he didn't have much time to complete what he considered one of his most important legacies, a reconstruction of Peraliya's drainage system.

Although he had no engineering experience, Mr. French hired two backhoes and a team of workers for a total of about $200 a day and set about coordinating the work on his own. His plan was to spot places were water was pooling and dig ditches nearby. But a major reworking of the town's drainage was too great a task. Mr. French sought help from World Vision, a large international Christian relief organization active in Sri Lanka.

After weeks of cajoling, World Vision agreed to take over the project. A World Vision official, Peter Read, later said the organization worried about having too many amateurs involved. "You really need to have a technical understanding" to do the job right, says Mr. Read, a World Vision construction adviser and drainage expert who worked on the Peraliya project.

World Vision wasn't able to complete the job and the project died. A key drainage ditch was located on land being used as a resting point for the derailed train. Some villagers also objected to digging trenches on or near their properties. "It got fairly political from our point of view and we don't like to get in those situations," Mr. Read said. Mr. French's earlier ditch-digging efforts, however, helped the town get through the monsoon season.

Mr. French had been in Peraliya for four months and he began to worry that the locals were becoming dependent on outside help. He had emptied his own bank account, spending some $15,000 in savings he had intended to use to buy land and settle down in Colorado. Most of the medical cases had been treated. The trains were running again.

Also, Mr. French's physical stamina was wearing out. After several months of robust health, he had fallen ill with a virus he mistook for malaria. He was also battling with other volunteers over whether to build a school on land he thought should be reserved for housing. Mr. French worried the school could become a monument to the volunteers instead of a useful addition to the village. The argument strained relations among the volunteers. "The inevitable group cracks are forming," he wrote in his diary.

Mr. French decided to spend the next several weeks tying up loose ends. He continued to run into headaches: Late at night, an unhinged villager began to uproot the 500 new coconut trees Mr. French bought for Peraliya from a Sri Lankan coconut-tree association. No one asked for the trees, but Mr. French had thought they would aid soil retention and could be a new source of income.

Other projects were coming together. In the neighboring town of Telwatta, for example, Mr. French came up with $3,000 to help rebuild the local bakery. Mr. French felt the town needed fresh bread each morning to feel normal again.

"I was doing nothing, just waiting" until Mr. French showed up, said A.G. Premarathina, 62, the town's baker, as he and two other men smoothed concrete to form the oven.

Finally, Mr. French made arrangements to return to the U.S. As his departure date approached, Mr. Darmadasa gave him a wood carving in the shape of Sri Lanka. Local kids painted a mural on a school wall that featured a giant ship with flags from the U.S., Australia and Italy. On board were characters based on the main volunteers. Mr. French was a monkey.

On his last day in late May, Mr. French felt somewhat lost. "It's a little weird" leaving, he said. "Some of these people I want to spend time with when we're old."

Today, Peraliya remains scarred. A fire earlier this month tore through the village, destroying 30 homes. But a new tsunami warning center has been completed and a permanent medical clinic is under construction. Driving along the coast recently, Ms. Thompson, the nurse, says she noticed "children were laughing again, dogs had fur and there were newly painted houses and shops."

Mr. French struggled when he went home. He was asked to sit on a panel discussing the tsunami during a film festival in Telluride but became annoyed with some of his fellow panelists who had spent little time in the disaster zone. He became so upset thinking about Sri Lanka that he couldn't speak.

But over time, lessons from the experience became clear. Most observers say the international aid community did a fine job in the days immediately after the tsunami, preventing disease and distributing supplies. But after that, many aid groups were too encumbered by their procedures to lead a quick reconstruction effort. Mr. French left Sri Lanka convinced that it takes individuals to truly make a difference.

That lesson is even more apparent, he says, as New Orleans grapples with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. When he heard about the disaster, he was saddened and then angry. As in Sri Lanka, the authorities were unable to respond fast enough. The gap was filled at least initially by the dedication of amateurs.

"This is a situation that's slogging along through volunteer efforts and people just coming out and doing it," he said, earlier this month.

For now, Mr. French has other responsibilities. One evening earlier this month, he found himself in Saskatoon, Canada, where his friends in Pearl Jam were playing to a packed house. Earlier in the day, he had visited a farmer's market, where he hand-picked produce for the day. On the menu: Braised rabbit and walleye pike sautéed over a bed of arugula with a light brown butter.

While waiting backstage for a set to end, Mr. French said he thinks about Sri Lanka every day. The screensaver on his laptop is a picture of Mr. Darmadasa. He is already looking forward to mid-December when Pearl Jam will play its last gig of the year. By then, Telluride will once again be covered in deep powder. But Mr. French doesn't plan to be there. He plans to be in Peraliya.