Mean Mean Stride: The Drums of Neil Peart

By Don Zulaica, DRUM!, October 2005

Flesh, blood, soul, and fire.

All essential ingredients to music of significance, and drummers worthy of any enduring memory have it all. Insert your favorites here.

However, perhaps more than any other instrument (your loudmouth guitarist friends are going to jump up and down - let them), drummers are attached to, and driven by, their equipment. We all covet those round wood cylinders, delicious metal pies, and hardware contraptions that, through increasing space-age innovations, make our lives easier. Who doesn't remember their first set (with either fondness or consternation), and who doesn't feel their pulses race when they get their hands on that special new piece of gear?

For some noteworthy drummers, there is an equipment history worth revisiting. This is the first in a series of DRUM! features that will examine the different setups of some of our (and hopefully your) favorites. So who's on first?

Neil Peart.

Historically speaking, Rush's drummer and lyricist is arguably the single best combination of rudimentary precision, mathematical meters, and Keith Moon's ferocious bombast. Don't confuse him with lighter-handed progressive peers: The man is rocker at heart. Take it from someone who has watched him rehearse - to paraphrase Keith Olbermann: He hits the drums, real hard.

Let's have a look at the drums and cymbals he has so lovingly pounded into submission.

Begin The Day With A Friendly Voice.

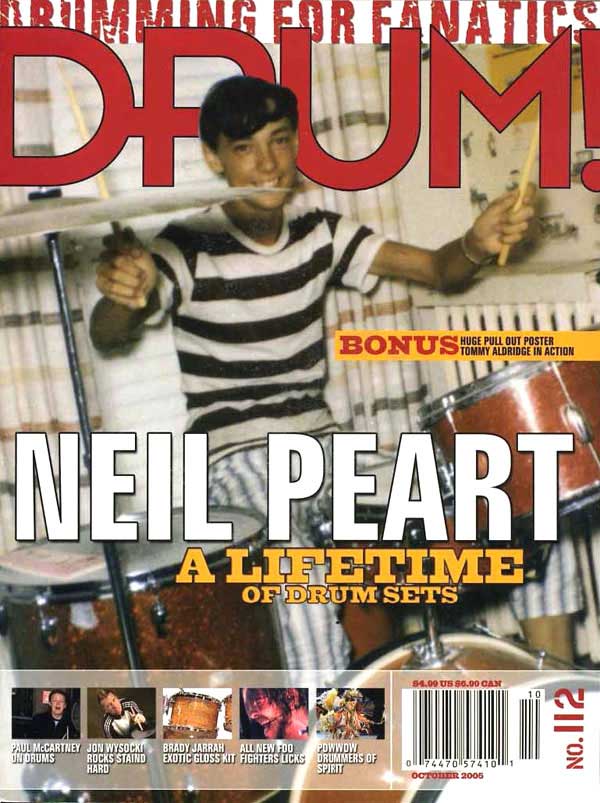

For his 13th birthday, St. Catharines-native Neil Peart didn't get a drum set. No, no. "I got a pair of sticks, a practice pad, and lessons," he remembers, adding that his parents told him, "'Once you show that you're going to stick with it for a year, then we'll get drums.' Fair enough. I'd do the same thing."

Of course, the lad voraciously ate up his sight-reading and rudimentary lessons with Don George at the Peninsula Conservatory of Music. One year and $150 later, Peart celebrated his 14th birthday pounding to "Land Of A Thousand Dances" and "Wipeout" on his very own red sparkle beauties.

"The brand was Stewart," he says. "It had a 20" bass drum, snare, 12" x 8" tom-tom, and one 16" Ajax cymbal. I later traded with a friend for an 18" Capri bass drum, and received a hi-hat for one birthday, and a floor tom for another, then eventually expanded to two Ajax cymbals, both set ridiculously high."

He played, and broke, Slingerland Gene Krupa model drumsticks, and because he couldn't afford new pairs, he simply turned them around and used the butt-end. This approach, enabling him to get more punch from lighter sticks, became a playing trademark for much of his career.

"At around 16, I got a Rogers Gray Ripple set," he continues. At a staggering $750, the drummer of the local-roller-rink-ruling Mumblin' Sumpthin' (his first "real band") delivered papers, mowed lawns, and worked for his father's farm-equipment dealership on Saturdays to make the $35 monthly payments. This Rogers kit "grew into a double-bass-drum setup with twin 12" toms and a 14" floor tom - I was all into those small sizes back then - and my first Zildjians: 20" and 18", set way up high, with 13" hi-hats, with the stand also extended way high."

Peart continued cutting his teeth with local bands like The Majority and J.R. Flood, and had an eye-opening trip to England in the interim, but of course we have to fast-forward this tape to 1974, when he happened upon two strapping young lads, namely Toronto-native bassist Gary Weinrib and a guitarist named Alex Zivojinovich of Fernie, British Columbia.

Working Man.

Better known as Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson, the two jammed with young Peart and offered him the drum throne - Rush's self-titled debut album had been nabbed by Mercury, and an American tour was beckoning.

Armed with a record-label advance, the excited drummer headed to a Toronto music store. It was there he bought his first touring kit, chrome-finished Slingerlands, which included two 22" x 14" kick drums, two 13" x 9" rack toms, a 14" x 10" rack tom, and a 16" x 16" floor tom. "I don't remember being particularly fixed on getting Slingerlands," he admits. "I think I just saw them on the music-store floor and fell in love with them." He also stocked up on some Zildjian cymbals, including 13" New Beat hi-hats, 16", 18", and 20" crashes, and what would be his right hand's best friend for the next few decades - a 22" Ping Ride.

Speaking of best friends, a certain 14" x 5.5" snare drum - the snare drum, the one that has been heard on countless live dates and albums from Rush's fabled catalog - was purchased around this time.

"The copper-finish snare drum," Peart says, "metal-over-wood - not the top-line model, but their second-echelon; I forget the model name right now, 'Artist' maybe? - was bought later in '74 or '75, second-hand, from an American drum store. That's the one I used for so many years as 'Old Number One,' repainting that copper 'wrap' to match subsequent sets of Tamas and Ludwigs.

"A previous owner had filed the snare bed lower in the shell, and that seemed to improve its responsiveness and sensitivity at all volume levels, making it extremely versatile. Even back then I often used other snare drums in the studio, but that was always the best for live performance - until I discovered the DW Solid Shell (outdoors) and Edge (indoors)."

For the Caress Of Steel tour, the kit took a more familiar look, as Peart added single-headed concert toms to the arsenal, measuring 6" x 5.5", 8" x 5.5", 10" x 6.5", and 12" x 8".

When asked where he got the idea for the additional voices, he replies, "I think Kevin Ellman, then with Todd Rundgren's Utopia, was the inspiration for wanting to add concert toms. He was so powerful and melodic with them. Nick Mason with Pink Floyd was also very effective with them on Dark Side Of The Moon."

He also added another 16" crash (6" and 8" splashes snuck in here at some point as well), which begs the obvious question: With all of this new stuff, how many people does it take to help move a drum kit? "At that time we had a three-man road crew, with the front-of-house engineer doubling as drum tech, or in the less-hip terminology of the day, 'sound man' and 'drum roadie.'"

La Villa Strangiato.

As the '70s rolled on, the band took lengthier trips into the multi-instrumental arena, which were captured on 1976's 2112, A Farewell To Kings, and Hemispheres. It was around this period that Peart started incorporating an array of percussion instruments (temple blocks, tubular bells, brass timbales, wind chimes, bell tree, triangles, and glockenspiel) around a new black chrome-finish Slingerland set. The village not only boasted new accoutrements, including an 18" Pang cymbal (with rivets, yet), but bigger houses. The kick drums got more big-boned at 24" x 14", the first rack tom switched to a 12" x 8", the third rack tom became a 15" x 12", 6" and 8" splashes became 8" and 10", and the floor tom bloated to 18" x 16".

Peart explains the changes, "The percussion stuff came more or less naturally, with the style of music we were making in that A Farewell To Kings and Hemispheres period - extended arrangements combining atmospheric and acoustic passages. All those tuned percussion instruments make such pretty sounds and look so good too!

"As for the bass drum size, I had noticed when I listened to other drummers from out front that 24" bass drums seemed to 'reproduce' the best, so I switched to that size for a while. Tom sizes were refined as I developed stronger tastes on how I wanted them to sound, separately and together."

These new Slingerlands were also "Vibrafibed," a process of putting a fiberglass coating on the inside of the drum shells, which was theoretically supposed to enhance resonance and attack (Peart did this with his next couple of kits as well). But did it help, really? "I'm not sure it was any big improvement, but it didn't seem to hurt!" For the Hemispheres tour, the kitchen-sink mentality continued with the addition of Zildjian crotales, an 18" Wuhan China, 20" Zildjian China, a gong, and a 28" tympanum. When asked why, he quips, "I think I was curious about the sound of anything you could hit with a stick."

Living In The Limelight.

What is considered by many to be Rush's true breakthrough period came in the early '80s with Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures. It was here that we saw his preferred drum brand change from Slingerland to Tama (Superstars, done to the same previous specs, and "Vibrafibed"), though Peart remained a staunch Zildjian cymbal man.

"I recall that Slingerland was starting to falter around then," Peart explains of the drum company change, "in terms of parts and service, and also seemed to be 'headless' - for example, no one from the company ever contacted me personally about any kind of endorsement, or invited me to get involved with the product in any way. Their drums still sounded pretty good, but the hardware was antiquated and fragile, especially compared to the sturdy stands and mounts coming from the Japanese companies at the time. Tama made a good-sounding set of drums, and their people were very eager to please, so I decided to try them."

In what would be the first of many moves toward having not just a large kit, but an elegant-looking kit, Peart had the drums stained to match some Chinese furniture he had at home. "Yes, a dark rosewood effect," he recalls, "created by mixing stains and inks. That was the first time I went for a custom finish, and the first time I used brass-plated hardware too."

For Moving Pictures, brass timbales went wood, and the tympanum was replaced with two single-headed Tama gong bass drums, sized 20" x 14" and 22" x 14". It was for the 1982 album Signals that an interesting shift occurred with Peart's kit. Not in terms of sizes, and not necessarily in terms of finish - Candy Apple Red with brass hardware (the man likes his red) - but in terms of shell makeup. Peart's next drums were a prototype of what would become Tama's flagship line, the thin-shelled Artstars. "During the mixing of our second live album Exit, Stage Left," he explains, "in the summer of 1981, I was hanging around Le Studio in Quebec with not much to do. They had an old set of English Hayman drums kicking around that had formerly belonged to Corky Laing from Mountain, and I started restoring them - taking apart each tension casing and cleaning and lubricating them, drum by drum, polishing the rims and hardware, and putting on new heads. When I put them together, they had a wonderfully resonant sound that seemed to be due to the thinness of the shells. Thinking about that concept, I related it to violins or acoustic guitars, or the sounding board on a piano, and Tama agreed to experiment with a shell design along those lines. That became the Artstar line."

Red Alert, Red Alert.

An even more dramatic shift occurred for 1983's Grace Under Pressure. Most of the percussion was retired in favor of an electronic drum set that included four red Simmons pads using a Simmons SDS-Vdrum module for sound generation, a Simmons Clap Trap, Shark trigger pedals, an 18" x 14" Tama bass drum, a 14" x 5.5" Slingerland snare, and a host of Zildjian cymbals (16" and 18" A Crashes, 22" Ping Ride, 13" New Beat hi-hats), and a 19" Wuhan China. To help make room, the timbale pair was cut in half, leaving one 13" metal timbale.

"Up to that time," he says of the electronic kit adoption, "I had been following what people like Bill Bruford and Terry Bozzio were doing with electronics, and it also happened that the material we were writing at the time was influenced by the stylistic developments in electronic music.

"Wanting to make use of all that, but not willing to sacrifice any of my acoustic drums, I had the 'brainstorm' of creating a satellite kit behind me and turning around to play it. I didn't think electronic bass drums, snares, or cymbals were up to the job at that time, so I used the acoustic ones combined with an array of pads and triggers, some of which I was also able to reach from the front kit.

"Between rehearsing and recording Grace Under Pressure, we played a five-night stint at Radio City Music Hall. By that time I had already incorporated the electronics into that first 360-degree setup, but didn't have the rotating riser yet, so I had to play those songs facing the back of the stage."

Things were kicked up a notch for Power Windows, as Peart started triggering samples from EPROM chips, which were loaded into the analog-digital hybrid Simmons SDS-7 module.

"With that 'Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory,'" he says, "I was able to make true samples for the first time, burning chips with specific sounds I liked, and triggering them through the Simmons pads. Although it was very primitive technology, it did allow me to use 'found sounds' (like the clinking 50-pence coins in the intro to 'The Big Money'), or even create my own sounds - by, for example, combining acoustic sounds with vocalized drum sounds, also used in 'The Big Money.'"

Turn The Page.

The tour to support 1987's Hold Your Fire saw another changing of the guard, kit wise. Sparing no expense, Peart lined up several different drum sets side by side and test-drove them all. Eventually he chose a Ludwig Super Classic set finished in an opalescent white, with some sparkles "and just a little pink mixed in." The company made some concert toms, including adorable 6" x 5.5" and 8" x 5.5" sizes, but Peart opted for double-headed drums all the way around when push came to shove. The sizes: 6" x 9", 8" x 9", 10" x 9", 12" x 8", 13" x 9", and 15" x 12" rack toms, with an 18" x 16" floor tom.

When asked about the switching to deeper small-diameter and double-headed toms, Peart replies, "Everything is a trade-off, of course, and though the open toms had powerful attack and definition, I always preferred the nuance and throatiness of closed toms - just more expressive, it seemed to me. Plus, instead of combining the open concert toms with all the other toms being closed, I decided I wanted to have the timbres of the whole set more alike."

Other notable changes included the addition of the MalletKAT electronic marimba ("a wonderfully useful instrument"), which took the place of his woodblocks, crotales, and glockenspiel, and Akai S900 samplers, which Peart played through Yamaha trigger-to-MIDI converters.

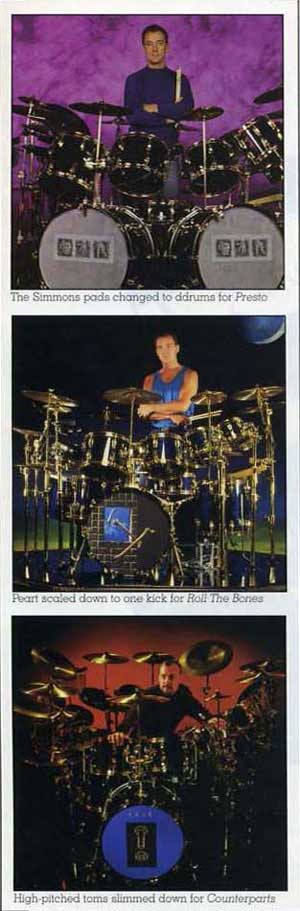

"I eventually amassed a huge library of sounds," he admits, "including all my old percussion sounds, previous drum sets I had used (like the Tama Artstars, which I often used as samples), lots of 'found sounds,' and a whole spectrum of ethnic percussion samples. All of those were on floppy disks and could be used in the Akai samplers." Little changed for the Presto sessions and tour, save for painting the white drums in a purple metallic finish, and switching from Simmons to ddrum pads.

The why is simple. "Can you say 'repetitive stress syndrome?'" Peart rhetorically asks. "Seriously, that wasn't a problem with the minimal amount I played the pads, but I know session drummers were having that problem. Mainly the ddrums were just nicer to hit than those Simmons tabletops."

You Bet Your Life.

Peart stayed with Ludwig for Roll The Bones (1991), with a new kit that featured a blue stain finish. Logistically, there were a few left turns: the two 24" kick drums turned into one 22" x 16" with a double pedal, and the 18" floor tom was moved to the left side of the setup, which effectively made the 15" tom the right floor tom.

"In the ceaseless quest for new approaches," he surmises, "and my horror of repeating myself, it was great to have a floor tom under my left hand - an unusual place to begin a fill, or to construct the kind of syncopated African-style rhythms I was much influenced by. Freeing up that space by eliminating the second bass drum seemed worthwhile, and the linked pedals had improved to the point of being reasonably efficient and reliable."

The higher-pitched toms slimmed down depth-wise - 6" x 5.5", 8" x 6", and 10" x 7" - and the timbale was replaced with a Remo Legato snare drum sporting a Kevlar head. "It was Mickey Hart who introduced me to that drum," he says, "and apart from solo accents, I think the only song it was used on was 'Stick it Out,' on Counterparts."

Of course, much happened between 1993's Counterparts and 1996's Test For Echo, perhaps most notably the Burning For Buddy projects, which saw Peart rub elbows with the likes of Matt Sorum, Steve Gadd, Max Roach, and Steve Smith. It was Journey veteran and fusion stalwart Smith who introduced Peart to master teacher Freddie Gruber. The subsequent technical transformation from matched to traditional grip has been well documented in the video A Work In Progress (Warner Brothers).

Resisting Everything But Temptation.

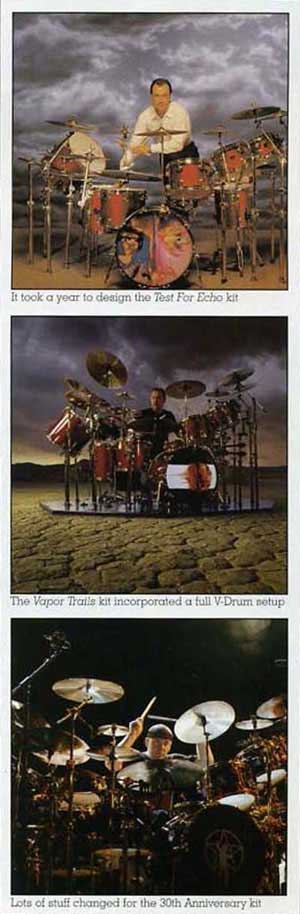

This technical evolution caused an equipment evolution as well. To accommodate for all of the "adjustments," drum sizes reported in at 8" x 7", 10" x 7", 12" x 8", and 13" x 9" for the toms, 15" x 12", 16" x 16", and 15" x 13" (on left) for floor toms, and an 18" x 16" floor tom suspended over and behind the 16" x 16". Peart stresses, "It took more than a year of daily practice to make those 'adjustments.'" The first version of this new kit - a DW - was finished in a custom Blood Red Sparkle, a nostalgic nod towards those $150 Stewarts.

Why the switch to DW? "Once again," he explains, "I did a side-by-side 'taste test' during the songwriting period, trying about six different brands in a really thorough comparison - because I had the time to give each one a proper test, and in the studio, where I could hear the results recorded on real songs." Echo also marked the retiring of the "Old Number One" Slingerland snare, resulting in some significant experimentation. Among the favored touring drums during this period were a 14" x 6" DW Craviotto (now called Solid Shell) for Echo, and an Edge model for the 2002 Vapor Trails tour. Peart has stuck with DW ever since, up to his Black Mirra 30th Anniversary kit, which features assorted band logos and album artwork, patterned after Keith Moon's Pictures Of Lily set.

"It was a tribute to that because these are my dream drums," he says. "I always try to keep in touch with my inner 16-year-old. That's the first concert I ever went to, he was playing those, the famous [set] that was painted in the panels around it on a piano black background."

Electronics-wise, the Vapor Trails period saw the back-end kit change from acoustics and ddrums to a full set of Roland V-Drums, and Peart even started using the electronic cymbals. "It was nice to finally dare to use electronic cymbals, snare, and bass drums, enhancing the contrast between the front and back kits."

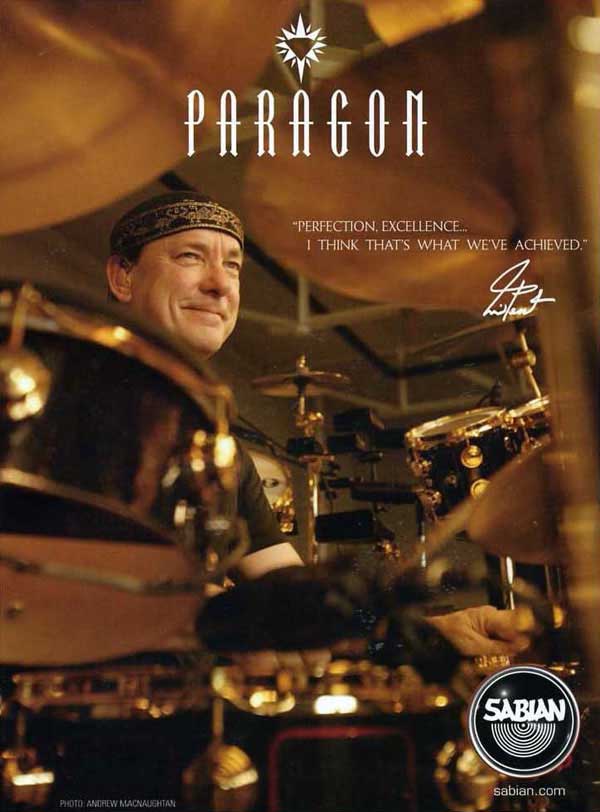

His acoustic cymbals? Perhaps the biggest change of all. Make no mistake, Neil Peart spent the lion's share of his career bashing Zildjians. He created quite a stir when he migrated to Sabian and developed what would become the Paragon line.

"It was one of those purely organic things that just came along," he comments. "I started hearing people playing Sabians and kind of got interested. And when I was rehearsing for the big Concert For Toronto with the Stones and all that, I just thought about trying out some Sabians. So I used them for the first three days of rehearsal or so, and then I said, 'Okay, take them down and put the Zildjians back up.' Frankly they blew them away. Even just their stock ones. So, hmmm [holds chin]." The curious Peart took a motorcycle ride to Sabian's factory and spent some quality time with master product specialist Mark Love, who "just seemed to get in tune right away with what I liked." The rest is history.

What the future holds for Peart's percussive equipment, nobody really knows - except that he will move forward with open ears for anything equally "irresistibly useful."