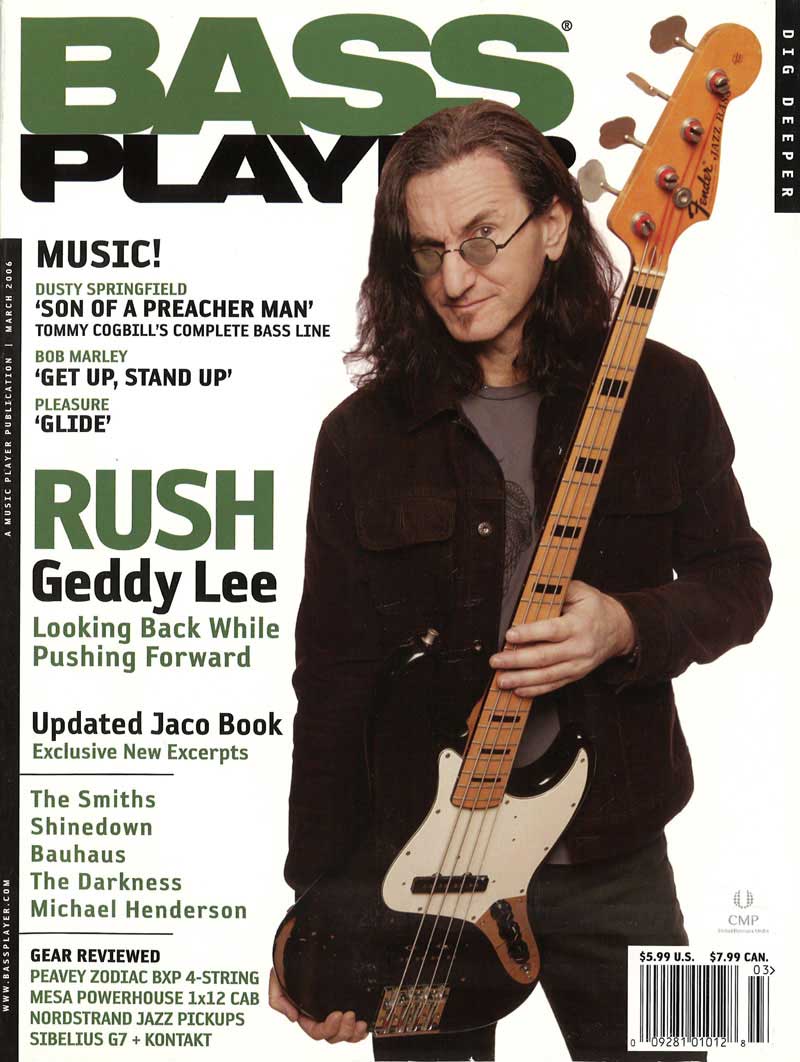

Living In The Limelight

After A Successful 30th Anniversary Tour, Geddy Lee & Rush Retreat To Record A New Album

By Brian Fox, Bass Player, March 2006, transcribed by pwrwindows

RUSH IS ROCK TO THE POWER OF THREE: THREE MEMBERS, each a master of his instrument. Three decades, each marked by its own sound and direction. And then there's Geddy Lee, the triple-threat frontman who is somehow able to command bass, vocals, and keyboards simultaneously.

Geddy is the rare type of player whose combination of talents create a fiercely original voice. His vocal shriek is unmistakable; his bass countermelodies, soaring and adventurous; his tone, aggressive and in-your-face. Combining Geddy's skill set with guitar alchemist Alex Lifeson's sonic concoctions and drum god Neil Peart's downright ridiculous chops, Rush achieves a sound that is huge.

Geddy has sought to make it even bigger through the years. He was one of the first bassists to utilize a stereo bass rig. Around 1977's A Farewell to Kings, he began using Moog Taurus bass pedals and a doubleneck Rickenbacker bass/guitar to create the lush soundscapes of the epic "Xanadu." That spirit of experimentation and ambition has driven Geddy and his bandmates since their beginnings as a blues-rock band in the tradition of Cream and Led Zeppelin. Shortly after Rush's 1974 debut album, the trio began to explore long, multi-part compositions with rhythmically complex passages, hitting its stride with 1976's prog-rock treasure 2112. 1981's Moving Pictures broke the band into mainstream rock radio with hits like the anthemic "Tom Sawyer" and the tweaked-out instrumental "YYZ." In the '80s, Geddy, Alex and Neil delved deeper into the world of synthesizers before returning to a rootsier rock sound in the '90s.

This spring, three little letters will make Rush fans very happy: DVD. On the heels of the band's R30: 30th Anniversary World Tour DVD/CD release, the three classic concert videos All the World's a Stage, Exit...Stage Left, and A Show of Hands will finally be released in digital format.

Past and present, one thing is clear from Rush's live performances: Geddy's having a blast up there. "Especially these days, there's such a positive vibe coming from our fans," he says after wrapping up yet another massive world tour. "They're so happy that we're still around. I really feed off that-It instantly puts me in a great headspace."

There is another big reason for Rush fans to be excited-the band has begun writing a new album of original material, the first since 2002's Vapor Trails. As his band shifted from stage to studio mode, Geddy reflected on his approach to writing, his experiments in bass tone, and the chemistry that makes Rush unique.

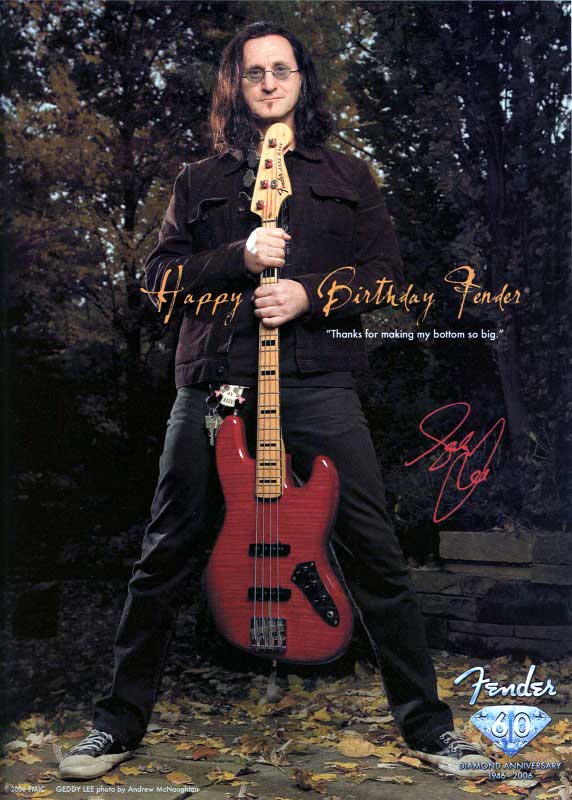

You've used a number of different basses through the '70s and '80s-Rickenbackers, Steinbergers, and Wals-but for the last ten years, You've used your '72 Fender Jazz Bass almost exclusively. Why?

When we started working on Counterparts [1993], the whole band started going in a retro direction, sound-wise. I went back to using an Ampeg SVT, and I rediscovered the glorious bottom end of the Fender-I haven't stopped exploring it since. The Jazz Bass has a really sweet neck, and I feel far more fluid playing it than I ever did on the Rickenbacker. The Ricky was a real slam-bam kind of instrument that I had to play more aggressively. The neck was pretty big, and the action was high, because that was how I got the tone I wanted.

What were your reasons for switching basses?

The Steinberger's size made it easier for me to move around between all my gear onstage. It had a really interesting midrange honk, but ultimately it had an unsatisfying tone. It didn't have the top-end snap and bottom-end growl that I like. I started playing Wal basses when we recorded Power Windows [1985] because they're beautiful-sounding instruments with a tight, snappy high end. At the time, there was a slight bit more funk in how I was playing, snapping strings and playing chords way up the neck. I used lighter-gauge Rotosound Funk Master strings, which allowed me to play chords without taking up so much space in the sound spectrum.

Has your tone changed very much through the years?

Yes, a lot. In the early days, it was clangy top end first, with a round but not overly aggressive bottom end. In the mid '80s I started crunching it up a bit more with distortion and compression. It's continued to change with every record.

How did you come to use the Moog Taurus pedals?

It was a way to get me on guitar. Around A Farewell to Kings, we wanted to have rhythm guitar behind some of Alex's solos, and we figured the best way to do that was for me to play my double-neck Rickenbacker bass/guitar, and fill in the bottom end with the pedals. We eventually started using it to sneak other melodic parts in, as well, to fill out the texture. That set me on a road of experimentation that got to be a little insane-we were basically trying to invent MIDI before it was invented. We built unbelievably complex machines, some of which were total failures.

I just accepted synth bass for a number of years, but I got frustrated not being able to play my No. 1 instrument. When MIDI came along, that changed everything. The combination of MIDI and sophisticated multi-note sequencers and samplers allowed me to make our records dense and interesting. And we've always been obsessed with being able to play our records live as a three-piece-we didn't want other guys onstage. So that meant an increasingly complicated array of tools to help us accomplish it. And we wanted it to be performance-based, not taped. Eventually, it got to be too much for me, so Alex and Neil started triggering our keyboard events, as well.

You've been playing some of these songs for 30 years. How do you keep from burning them out?

Sometimes just giving a song a rest and coming back to it can be great. "Working Man" is one song that we were totally bored with, and we gave it a break. We brought it back for the last two tours, and it's been really refreshing. It's a real three-piece jam song, and we all just have a blast.

After playing with Alex for so long, I imagine you could identify him after hearing only a few notes. What are his stylistic hallmarks?

He's one of the great builders of odd chords, and there's a very particular way he arpeggiates them. As a soloist, he's got a fluidity and a freedom of movement around the neck that's quite original.

How would you describe Neil's rhythmic sensibility?

In many ways, Neil's more rooted in jazz than in rock-even though he rocks pretty darn well. I think in his heart, he's a jazz player who's adapted to rock. He likes to play on the very back end of the beat. When he wants to rock, he'll flip his sticks over and use their butt ends, and when he wants to be more nuanced, he'll play with the tips, and he goes into a whole different kind of swing. He just has an incredibly deep tool kit, so many things to pull out. Plus, his hyperactivity is pretty well known.

Do you play bass in your down-time?

From time to time. Once in a while I'll go downstairs to my home studio and just pluck around. And I keep a bass lying around so I can just run my fingers up and down the board if I'm hanging out with the kids or watching TV. But I don't pay any serious attention to it unless I've got something coming up.

Do you find yourself losing facility after a break?

I used to really feel a fall-off when I was younger. Now I just feel refreshed. Alex has found the same thing to be true. It just takes less time to get back in shape. It used to be downright painful if I went too long without playing.

Does songwriting feel natural, or does it take a lot of work?

I have to really sit down and make myself go to work. But this last tour cycle lasted two years, and I'm ready to change gears. Working with new people is instantly inspiring, but if I'm going to be writing with Alex and Neil, I like to lie fallow for a while. Then when we do get together, I'm fired up to play. That's how I feel now-I'm dying to get to work.

Has the writing process been the same for every record?

It's always a little different. We never know what's going to happen until we get together and sit down. It usually starts with Alex and me getting together to have some dinner, drink some wine, and talk about what's been on our minds musically. Then we'll organize a writing room for ourselves with some decent sounds and good instruments, and try to make sure we're not bogged down by too much technology so we can jam freely. I'll have my Jazz Bass, and I'll keep my Taylor acoustic handy in case I have a guitar idea that I think might work. We'll start at my home studio, where I have a Logic Audio setup that I use to grab all our jams. If I feel there's something spontaneous and wonderful in those jams, I can cut them out and use them later.

What are some of the ideas you guys have talked about?

We've talked vaguely about what stylistic frustrations we have from the past, and about certain feels we'd like to achieve. We see what we have in common; then when we get together, we know that's at least a starting point. That's important for us-we always like to have something to work on before we get into the studio, as opposed to starting with a completely clean slate. But usually the end result bears no relation to our initial conversation anyway-it takes on its own life.

For early albums, I don't imagine you had the luxury of writing sessions.

Yeah, the early stuff we just wrote whenever we had a minute to spare. Sometimes it would be in a car or hotel room, often on acoustic guitar. As we got more time to make records, we'd set aside the time for writing sessions. In the early days, it was just the three of us rehearsing in a room, banging out ideas and screaming at each other. Over time we started getting more formalized, with Alex and myself splitting off from Neil so he'd have a quiet place to write lyrics while we throw the jams together. As we've gotten older, we've gotten a bit more complete in terms of Alex and my jams. When we present something to Neil now, it's well down the road to being a song structure. With Alex, I find that after a long time off, invariably the first few things you write are really crappy. I'd like to get those out of the way without burning time on the clock. So we're going to try writing in a more relaxed manner.

Do you feel yourself drawn in any particular direction?

We have these ideas of how we imagine things might go, but once we start playing, that all goes out the window. The spontaneity in how we recorded Feedback in a short period of time, playing off the floor, has stayed with me. I'd like to take that attitude into a longer piece of Rush work. Regardless of how the writing sessions go, when it comes time to record, that's something I'm keeping in mind-trying to make those sessions less laborious and more spontaneous.

Which typically comes first, your bass lines or your vocal melodies?

It can go either way. If the vocals come first, I'll use bass like a guitar-to create a structure around that vocal melody. Then, if Alex likes that idea, we'll build a structure, and we'll decide if that initial bass sketch is still appropriate. If it's not, I'll write a line that better fulfills the song's bottom-end needs. Once Neil comes in, the bass track may change again. Often his approach to the rhythm will change what I do on bass. I try to bridge my initial idea with Neil's new input.

Neil has a new instructional video. Have you ever thought of doing one?

I've thought about it, but I don't see myself as much of an instructor.

What's a lesson you'd try to tackle?

Job responsibility. As a bass player, it's important to know the rules-and the best ways to break them. First, pay respect to the rhythm section, and make sure you're making the drums groove. Then look for ways to bring in melody. That's how I see my job, so maybe that would be interesting for other people to think about.

What are some of the ways you push yourself creatively?

The danger with playing bass is in looking at familiar blocks on the neck and always going there. It's most important to find different note combinations and not fall into those same patterns. I force myself to push beyond them, often by using double-stops or chords.

When I'm recording, after I take one pass, I'll often have another go, to try a fresh approach. I find if I pretend I'm a lead guitar player, I can get into a new melodic area where I wouldn't normally find myself. I'm typically more concerned with keeping things rock-solid on the bottom. At the end of the day, it can result in a bunch of self-indulgent nonsense, but sometimes it'll do interesting things to the melody. I like that kind of experimentation.

Different Stages

Here are some things Geddy Lee shared with Guitar Player way back in June 1980: "Cream was the first band that got me interested in music. I learned to play bass emulating Jack Bruce. From then on, I listened to bands like the Who and Jeff Beck. I was mainly interested in early British progressive rock. Led Zeppelin really blew me away-I became a real student of that heavy school of rock.

"I was using LaBella flatwounds for a few years. Then around 1972 there was a big turning point for my sound when I discovered Rotosound roundwounds. It was like, Wow - high end! At the same time, I got interested in Sunn amplification; John Entwistle [the Who] was using Sunns, and I really loved the sound that he used to get. So I got a 2000-S tube head and two cabinets with two 15s in each. I didn't care for the original speakers, so I replaced them with SROs.

"When we got our first advance, the first thing I did was run out and buy a Rickenbacker 4001. I was a big fan of [Yes's] Chris Squire back then, and he was using one. He and John Entwistle had the most innovative bass sounds, and I always admired that. I wanted to go stereo onstage, so I bought an extra bass setup: two Ampeg V-4B bottoms, and an SVT head. For my low end, I ran the bass pickup through the Ampegs, and the treble to the Sunn. I have my low end directly fed into the PA, while the speakers for my high end are miked.

"I used the Rickenbacker on nearly every track on Fly by Night. But on 'By-Tor and the Snow Dog,' a fantasy tune that featured characters representing good and evil, I was given the role of By-Tor, the evil one. So I developed an interesting sound-there's a monster sound that growls during one really chaotic musical segment. I put my '69 Fender Precision Bass through a fuzztone. It was distorted all to shit; we added phasing, and ultimately put in everything but the kitchen sink. I had all that sound going through a volume pedal,so every time the monster was supposed to growl, I would lean on the volume pedal. It sounded like a real monster!

"We went through a period after Caress of Steel where our music wasn't well received at all. It was a pretty naïve album in retrospect, but still an important one. We did a lot of experimenting with sounds. We've always felt that if your music is interesting, people will like it. It's a very simple philosophy. We didn't want to try to aim our music at the lowest common denominator. In fact, we felt compelled to do the opposite: try to make the music more interesting. We were growing, and we were going through changes, becoming more complex. The more we played, the better we got at playing, and the better we got at playing, the better we wanted to become.

"2112 was the first album where it was clear there was something happening-the beginnings of a sound that said, 'This is us. This isn't anybody else.'"

Feedback - Geddy's Direct Approach To Stage & Studio

"In the old days, the sound pressure levels from booming amplifiers made me feel disconnected from my bass. I started using in-ear monitors a long time ago, because they give me more control over my bass sound. Cabinets sound sluggish. I like that immediate feedback of the strings hitting the neck.

"My stage and studio setups are essentially the same: I take a flat signal from an Avalon U5 DI, one from a Palmer speaker simulator, and one from a SansAmp RBI. I change the blend depending on how nasty I want the distortion. I usually use the Palmer unit's BRIGHT setting to give me some extra twang. That gives me some reaUy interesting distorted subsonics.

When I combine the Palmer with the SansAmp, whieh I set up to give me some extreme highs and lows, I get the twang plus a round bottom end. In the studio I sometimes make a mulch of the signals, compress the hell out of it with a Urei 1176 and put it back into its own channel, just in case I need a different sonic shape-if there's a hole in the sound."