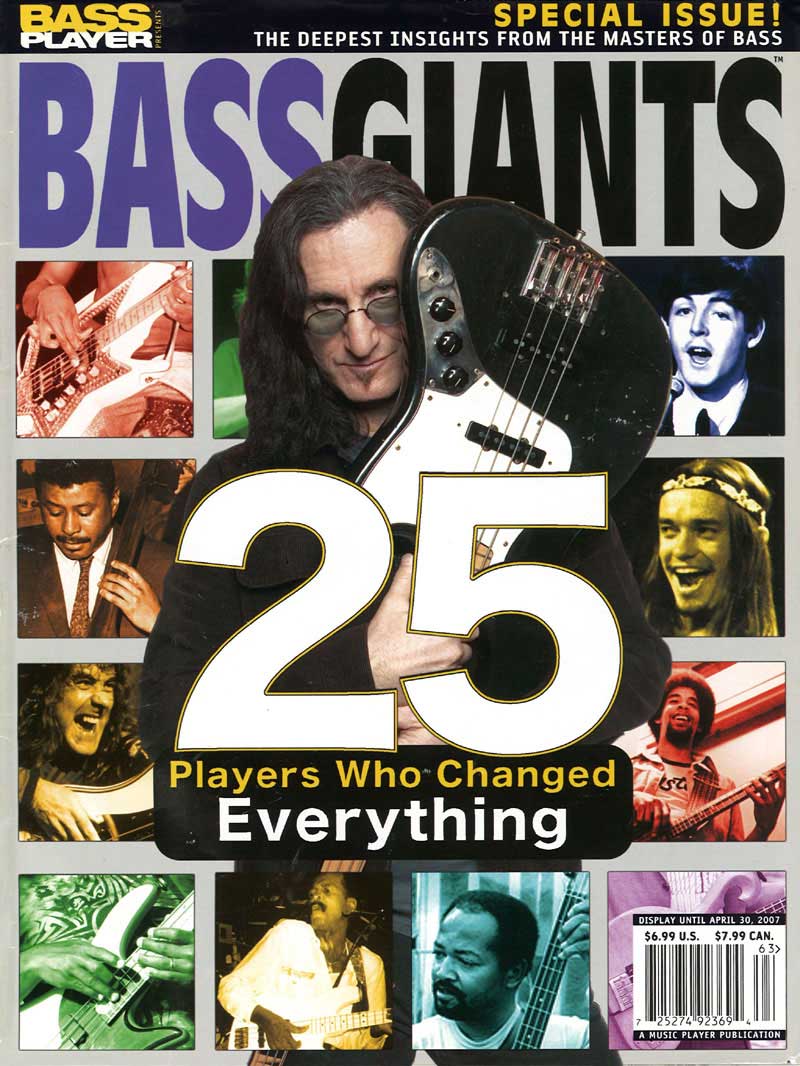

25 Players Who Changed Everything: Geddy Lee

Bass Player's 'Bass Giants' Special Issue, October 2006, transcribed by John Patuto

Geddy Lee's high-end twang and low-end bite on bass - not to mention his characteristic vocal shriek - have been key elements in Rush's progressive rock mix since the trio's 1974 debut. Geddy's serious chops continue to inspire legions of bass players.

As a bassist who plays a lot of notes, how do you make your parts fit?

I think the bizarre nature of our music allows for more notes. First of all, we have a hyperactive drummer, so it makes for a busier rhythm section. When you think of Rush, you don't think of a sedate rhythm section. But we try to hold the "chops" side of our music in reserve and save it for the appropriate moment. We always allow for that moment to exorcise those demons, and when the moment comes, we let it rip. That way, if there's a tune that's a little more reserved and we get frustrated about not being able to smoke on our instruments, we can think, "Hey - there's this song coming up and we can play like maniacs then."

What is your approach to composing bass lines?

In every tune, there's something that makes the song, and every other part has to serve that element. If you're having trouble figuring out when to be busy or what's wrong with the arrangement, try to boil it down to the one element that makes the song potentially great, and build your arrangement around that.

Over your career, what qualities do you think you've developed most?

I guess it would be knowing when to groove and bite my tongue - when to stay out of my own way. Sometimes I view my job as being the element that keeps the rhythm section smooth, that tries to make it feel groove-oriented. Early in our history, the groove wasn't so important; a lot of the stuff we wrote was intentionally herky-jerky, with shocking meter changes and things like that. But later, we've tried to make music that has a little more soul to it, and I view my role as smoothing out any rhythmic things that are uncomfortable - to make the rhythm section sound more fluid and glued-together.

We're always trying different musical approaches, and we try to emphasize different aspects of the rhythm. But it seems no matter how hard we try, we can't leave the music uncomplicated. Somehow, the "player" sides of our personalities always sneak into the crafting of our records, and I think that's what appeals to a lot of young musicians.

Do you agree with players who say the groove is sacred?

Yes, but it also depends on where you are - what stage of development you're at and what kind of music is turning you on at the moment. Sometimes it's not the groove you're going for; it's more math. At some point you have to appreciate that certain musicians get turned on by playing with the math, and that's okay. But that doesn't mean anyone else is going to like it! If you're going to play with math, do it because you love to do it - not because you expect anyone else to dig it. But if you want to make music that comes from any other part of your body than your head, you have to serve the groove. When I try to lock into a more repetitive, groove-like thing, I've found it's not about playing fewer notes - there are still the same number of notes per bar - but there is less of a variety of notes per bar.

What are some of the ways you push yourself creatively?

The danger with playing bass is in looking at familiar blocks on the neck and always going there. It's most important to find different note combinations and not fall into those same patterns. I force myself to push beyond them, often by using double-stops or chords.When I'm recording, after I take one pass, I'll often have another go, to try a fresh approach. I find if I pretend I'm a lead guitar player, I can get into a new melodic area where I wouldn't normally find myself. I'm typically more concerned with keeping things rock-solid on the bottom. At the end of the day, it can result in a bunch of self-indulgent nonsense, but sometimes it'll do interesting things to the melody. I like that kind of experimentation.

Has your tone changed very much through the years?

Yes, a lot. In the early days, it was clangy top end first, with a round but not overly aggressive bottom end. In the mid '80s I started crunching it up a bit more with distortion and compression. It's continued to change with every record.

If you were to teach a class on playing bass, what's a lesson you'd try to tackle?

Job responsibility. As a bass player, it's important to know the rules - and the best ways to break them. First, pay respect to the rhythm section, and make sure you're making the drums groove. Then look for ways to bring in melody. That's how I see my job, so maybe that would be interesting for other people to think about.

Essential Listening

Rush, Moving Pictures [Mercury, 1981]

Gear

'72 Fender Jazz, Rickenbacker 4001, Rotosound Swing Bass roundwounds; Ampeg SVT and Sunn amps, Tech 21 SansAmp Bass Driver DI; Palmer speaker simulator; Moog Taurus bass pedals

Geddy Lee on John Entwistle

John Entwistle was one of the quintessential rock bass players. Jack Bruce and Jack Casady [Cream and Jefferson Airplane] were my main influences, but certainly John was and still is very influential on my style because of his bold attitude and tone. He was the first bassist to have that great trebly sound; he wasn't just relegated to the nether regions of the bass spectrum. The Who had a tremendous impact on Rush, and [drummer] Neil Peart and I were particularly inspired by how Entwistle and Keith Moon played as a rhythm section. I never met John, but I saw him perform live numerous times, and I was told he was at some of our shows. It's a heartbreaking, tragic loss that a musician of his magnitude is suddenly gone.