Mike Portnoy Interviews Neil Peart

Rhythm, January 2007, transcribed by Ed Stenger

Rhythm gives you front row seats for a once-in-a-lifetime meeting of minds between two of the biggest talents in the drumming world. Neil Peart gets the fifth degree about drumming and life from one of his biggest fans, Mike Portnoy.

Sitting in a New York City cab, in heavy traffic, Mike Portnoy explains how he not only managed to score an audience with the famously private and rarely interviewed Neil Peart, but that the iconic Rush sticksman was actually the first of his four dream interviewers to come forward and commit to taking part, "I emailed Neil and told him I was guest editing this issue of Rhythm, and would he agree to meet for an interview - and he said yes!" says a clearly thrilled Portnoy.

Anybody familiar with Portnoy knows how large the legacy of Peart looms in the drummer's life. "Throughout my career," he says, "there is no other drummer I have been compared to and asked about as much as Neil." Indeed, Peart stands as the main influence for a whole generation of players affected by his energetically inventive playing and challenging technical finesse. Peart has manned the drum throne with Rush for more than 30 years, constantly evolving as a drummer and lyricist, and maintaining a fresh approach to his instrument and craft.

The last nine years have been no exception: despite tragic personal losses, Peart undertook an inward personal journey that saw him recommit himself to his music and his life. One offshoot of this has been a career in writing; Peart has published four books chronicling his many travels, the most recent being Roadshow: Landscape With Drums, A Concert Tour By Motorcycle. As luck would have it, Peart is in New York to promote the new book at the same time Portnoy is ensconced in a recording studio across town, working on Dream Theater's new album. The stars were aligned and the stage was set - the meeting of the professor and the apprentice was to take place at Peart's hotel.

Portnoy and Rhythm are greeted by Peart and after introductions and some comparing of road stories, the two drummers settle down onto a leather couch for what turns out to be the most comprehensive interview Peart has ever done. Peart is thoughtful, but with a great sense of humor, humble and serious about his gifts and his art, and eager to share his thoughts about drumming, music, and life. When Portnoy asks for Neil's patience since he's never been on this side of the microphone before, Peart puts him at ease: "it'll be fine," he says. "It's not hard for drummers to find things to talk about."

For the sake of Rush fans everywhere, I must ask how things are progressing on the new album.

"It's the first time we've lived so far apart - I live in Los Angeles and the other two guys (Alex Lifeson, guitar and Geddy Lee, bass/vocals) live in Toronto - so we thought we'd try long distance. I was working on some lyrics and I sent them up to them, but it was frustrating knowing that if I was there we could talk about this or that and I could hear what they were or were not working on.

"So we met up in March at my house in Quebec and they played me some of the stuff they'd been working on. I was impressed with how fresh it was and how different it was from anything we've done before. Funnily enough, as they're playing it for me, they're hearing all the flaws - you know how it is the first time you play something for someone, it sounds totally different. All of us were saying, "I know what we have to do here", so we decided we had to get together and work in the same place. So we spent the month of May in Toronto just working every day together, building things. It was so satisfying after all these years that something was fresh and exciting for all of us.

The interesting thing that happened was that there wasn't a conflict between all of us, it would be us against the song. It was all a sense of unity but the common enemy was the music that we were going up against. But we've got about eight songs that we really like, so by the time we get to that point it's pretty much a done deal. So we're going to start again next month, refining those and writing a few more, and then we're looking for someone to work with. We always like to have another voice in the studio. Someone who can say, "Why don't you try this?" or "That's not so good". We love to have that kind of input, so we've talked to a few different people and we've listened to different people's work to see who might be interested. We found this guy Nick Raskulinecz, who has worked with the Foo Fighters before and who is very young and enthusiastic with a very interesting career path, and just wanted what he's doing so badly that he chased it from Tennessee to LA. It's at a point right now of having the confidence of new material and the excitement of the unknown of working with somebody you haven't before.

I don't know about you , but I love the demo. The creative part of just trying things and playing it over and over. For me it's competitive against myself when I listen to it and say, "I can beat that!" and then work on another song and come back to that once night after night. The daytime tends to be split up into individual work, and at night Alex will be my producer and we'll work on drum parts. I have a built-in sense of when I can't beat it any more. Alex does the drum parts for the demos, and because they're so quirky and non-drummer like, I get really neat ideas that I wouldn't have thought of."

In the earlier days when you were playing longer, more progressive songs, I can't picture those earlier songs being written without all of you being present.

"Yeah. That has a certain value that we try to capitalize on now, and if we feel that something needs that we take the trio approach. When we did the cover tunes on Feedback it was like that, where we learned them all in the studio playing together, but we used to find in the old days, if we were all playing at once, it was counterproductive in so many ways, so we've learned by experience and try to do both. But yeah, if there's something that will benefit from the 'jamming it out' approach, we'll use that, but for the most part everybody has clearly defined roles. For instance, all the writing does come from jamming and Alex, being the more spontaneous once, comes up with stuff and then it blows by and later, Geddy being more methodical, will sift through it and combine it and do the Pro-Tools thing and sketch out an arrangement. So it's taking advantage of spontaneity and organizing it and being able to rehearse.

"I love being able to practice and go over my parts repeatedly. I love rehearsing. Geddy always jokes, "You're the only guy I know who rehearses to rehearse!", because before a tour I'll go in and practice for two weeks by myself. It's just a dynamic that's become really defined over the years and it works for us."

I'm very much the opposite; I can't stand the rehearsing.

"A lot of people can't. I always read that about Buddy (Rich), he couldn't stand the rehearsals. He didn't come to rehearsals. The rest of the band would rehearse and he'd come in, listen to the song and play it. It's great if you can do that, but I can't."

Dream Theater's last few albums have been made in the completely opposite way. We move into the studio and write. Each has their pros and cons. It's nice to be able to write something in advance and have time to refine it and develop it. This other way, sometimes I think I have a shorter attention span when it comes to my parts, so there's something enjoyable about writing something and capturing it while it's fresh.

"Yeah. The nice thing about working with a demo is being able to listen to something like that, especially if it's done in a no pressure situation and nobody else is waiting for you to learn the song. It's a matter of character. For me, I'm insecure enough that I want to get it good before anybody hears it and also not feel like I'm wasting someone's time. We used to find we'd be tripping over each other and Geddy would be changing his bass part or me my drum part. It is a matter of collective character. We just found something that the three of us, as individuals, like."

Throughout the '70s and early '80s, the characteristics of Rush's music that were very appealing to musicians were the long songs and untraditional arrangements. Do you ever miss that approach to writing - the longer songs and non-linear format? Do you guys ever discuss that?

"Fair enough, but no. Essentially, with a lot of that stuff, once you've done it, you don't really feel like you want to revisit it. Even at the time we knew that. Like when we finished Hemispheres, I remember having a conversation saying, "We're never doing this again, never going to work on that scope again". I love a lot of that stuff and we love playing it so it's not any kind of rejection of it, but it's something that we grew through and, as a drummer or as young musicians, you go through stuff, you learn to do a long piece in seven, and it's fantastic, but once it's done, do we want to do another long piece in seven? No, we've done that. So it becomes a constant exploration of what you really like and what makes you hungry now. Even when I got immersed in different things - African drum solos or whatever - I would want to incorporate that into my playing, but it's kind of an education too.

"In the beginning it was all about playing, all we were interested in was playing and technique and experimenting with really unorthodox arrangements. Those were really natural things for us to do, there was no plan, it's just what got us excited. Later we got more interested in arranging in a focused way, and the song, or course. For anyone who's involved in songwriting as opposed to playing, it becomes a lifelong commitment. How to express things better, how to present them better, how to communicate the idea. I was having a conversation with a musician friend of mine about the idea of being commercial, and I said that was kind of a dirty word, but how about 'accessible'? If you are trying to communicate something, make it accessible so that people get what you're trying to say. I go through the same thing with prose writing. It's up to me to make it clear. I learned something from a book called The Elements of Style, what does the reader need to know? If I'm writing a song about frustration, how can I make the words convey that most efficiently? Imagery and metaphor all become tools for that. So to get back to your question, we still play and love the long instrumental stuff, but because it's part of our repertoire, there's no need to do it again."

As a fellow lyricist, I am curious about the creative process of your lyrics. Not the words themselves, but the melodies. Is that something you and Geddy work on before you write the words? With us, we'll construct the melodies and then I'll write the words to them.

"That's interesting. It kind of does go both ways, but often it's easier that words on a page give you a kind of map to go by. This time is a good example because we were so far apart. I had a whole bunch of stuff kind of mapped out that way and sent it to them, and then Geddy and Alex jammed out some material and then Geddy would look through it and say, "Oh this might work with that". They will get twisted enormously in the way they have to fit in the piece of music, so lines of verses will get dropped here and there. Then I go back and try to stitch it. There was one time during our main session that the music and the words married beautifully and to hear certain lines being sung was like, 'Yes! That's the kind of depth I'd wished that line was going to have'. I was struggling for days with what was left of it trying to weave it back into some theme that made sense again and it caused me a little frustration, but then there's the freshness of Geddy singing them and finding a take on it that works for him. He'll come back and say, 'This one isn't working for me', or 'If I just had three more words here...'"

So there's a lot of rewrites?

"A lot of rewrites and give and take and again, I enjoy that. First of all, you've got a vote of confidence that he liked it and the guys have worked out a song that has the words in it and, if you can just do this and this, then they'll really like it. I get inspired by it and run off to my little room. So it's for us very much collaborative."

I'm curious how you track your drums. Is it one successive process throughout the course of several days until it's finished, or does it spread across the session through several weeks or months?

"No rules there really. Two examples would be Test for Echo, where we had done all the writing in pre-production and went down to Bearsville and did all the tracks in two days. Vapor Trails was completely different. We had the little studio in Toronto we moved into and worked there every day. As I worked on drum parts there was never the sense that 'this is the master'. Every night I just kept saying, 'I can beat it', and eventually you get one and it's good and you leave it and go on. Over the course of the year or so they came out one by one at long intervals. Sometimes we'd redo one or rewrite the song. So, two recent studio albums, two completely different ways to go about it."

What about the tracking itself, is it something you'll do a full take and punch in or do multiple takes?

"Test for Echo was nearly all full takes. If I'm looking for something spontaneous, I think that's where punching in is a magic thing. Where you can get the meat of the track down and say, 'Ok, I want something special here'. You can't plan that. When we worked on Test For Echo, I was just starting to get into that mode and starting to feel like tracks previous to that were stiff and over rehearsed. What I would do is work out the tracks top to bottom, but not let myself say, 'This fill goes here, this one goes there'. I would just say 'These 20 fills will work', and let them come out organically, so I had to play the whole song as a performance because there was no knowing where a certain fill would come out. Peter Collins (producer) came up with a great phrase: 'Don't leave spontaneity to chance'. My way of approaching a song is to try everything, and not to start simple and build it up, just throw anything in that might work and eliminate the ridiculous and the impossible."

And then have to learn it all...

"That's a funny thing that happens in accidents. In the old days when we would be out there thrashing away all together, you would use editing in the tape days, and sometimes through that meandering and experimenting, something accidental would happen. 'Tom Sawyer' is a perfect example of that. In the middle of the instrumental section I got lost, and it just went (flails his arms) and it brought me out great. To learn it afterwards became a funny challenge."

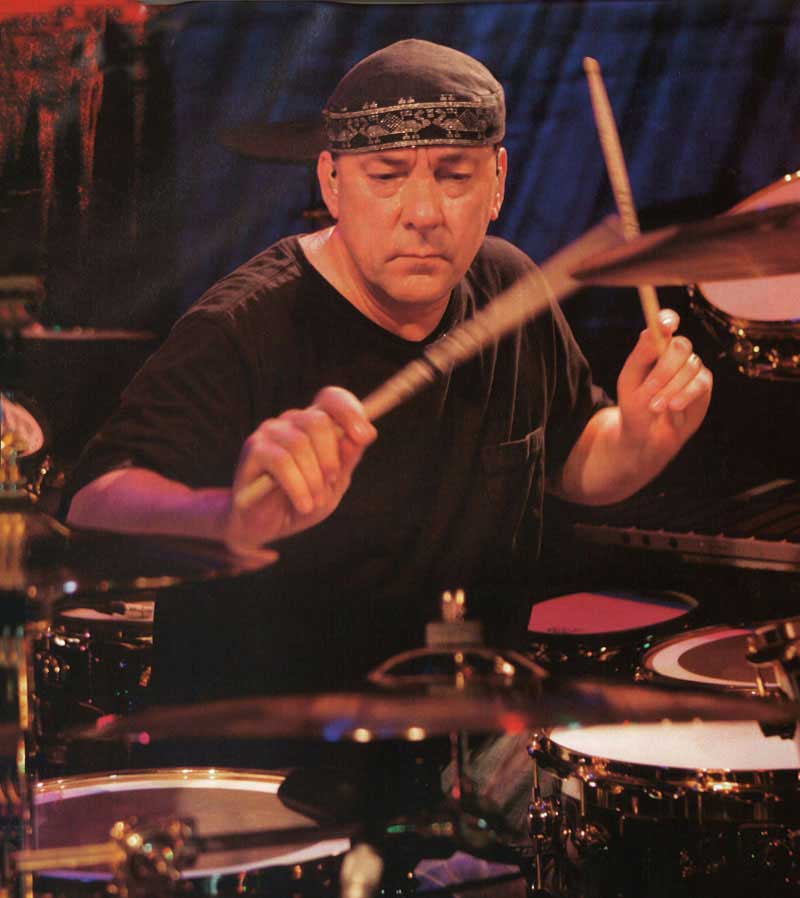

Almost 10 years ago, you famously 'started over' and began to refocus on your drumming by studying with Freddie Gruber. Your process and development throughout that period has already been well documented. Where are you at today in that development? Do you still practice as regularly as you were during that period? Do you still work with Freddie?

"I just saw Freddie the day before yesterday. I've compared Freddie before to a tennis coach; no tennis player needs a tennis coach to show them how to play tennis but they watch the way you move and inspire you. So yeah, I still use Freddie all the time and if you're sitting in his living room, he'll pick up a pair of sticks and start talking about something. So it's a different level of drum lesson now. We're not sitting at the set and working on a pad but it's always part of our dialogue. It's about drumming and movement, and he'll talk about how Papa Jo Jones did this. He's a walking history book, he's almost 80 years old now.

The practice thing is funny. At that time I was practicing religiously every day, all the stuff that Freddie gave me, and now I find at the end of a tour I don't want to play for a while. It doesn't stop me from being a drummer. It doesn't stop me from listening and being inspired by drummers. Like last year, going to see Joey Heredia play - his approach to time was so inspiring. I also saw Roy Haynes, a whole other thing and so inspiring. Here's another 80-year-old musician playing so beautifully in the music. I was sitting there with Jim Kellner, Ian Wallace, Joey Heredia and Freddie. So you never stop being a drummer, and when I went back to it in the spring, seriously playing every day, I had so much new stuff to work on. Hearing things people were doing or just listening to music all the time."

This issue is all about drumming influences. The focus is on the drummers that shaped me in my early formative years. Let's talk a little bit about your influences. To my ears, there are three drummers who preceded you who I can hear an influence in your early style... Tell me if I am accurate, and what are your thoughts on each of them?

First, Buddy Rich...

"Funnily enough not at that time. I have to say he was somebody I was only able to understand later. When I was growing up I used to see him on The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson and be blown away, but there was no connection for me. I can still remember hearing him play "Mercy Mercy" on that show, but my first influence really was Gene Krupa and The Gene Krupa Story. Until I got involved with the Buddy Rich memorial concerts in the '90s and the album, I didn't know that much about his drumming and his music, so it was amazing at that time to get immersed in it, to learn those songs and get to understand how his mind worked."

The next drummer who I can hear a bit of an early influence is Keith Moon. Having done a Rush tribute and a Who tribute back to back, I was able to see the surprising similarities between the two of you. Although you are an incredibly disciplined and calculated drummer, and Keith was completely reckless and spontaneous, somehow I can still hear a lot of his influence in your early style, especially on Fly By Night.

"Yeah. It's his phrasing for me. It's a constant and continuing influence. I saw a TV documentary on the making of Who's Next, and Roger Daltrey was in the studio just bringing up the tracks and talking about how Keith Moon framed the vocals. It's so obvious from Tommy and Who's Next and his mature playing just how sensitive he was to the song. I absolutely still use phrasing ideas from Keith Moon because that was his magic. He seemed to play chaotically but it wasn't - it was an intuitive sense of musical phrasing."

The third influence, and tell me if I'm right on this, is Michael Giles of King Crimson? Some of Michael's playing on In The Court Of The Crimson King, especially his snare work, could easily be mistaken for your early drumming.

"Oh, big time. Not only the early King Crimson but MacDonald and Giles too, it is everything I wanted. It was both disciplined and exciting. He was so fired up by what he was doing, but it was contained within a structure. His fill construction and sense of ensemble playing and orchestrating a part was unparalleled and very underrated."

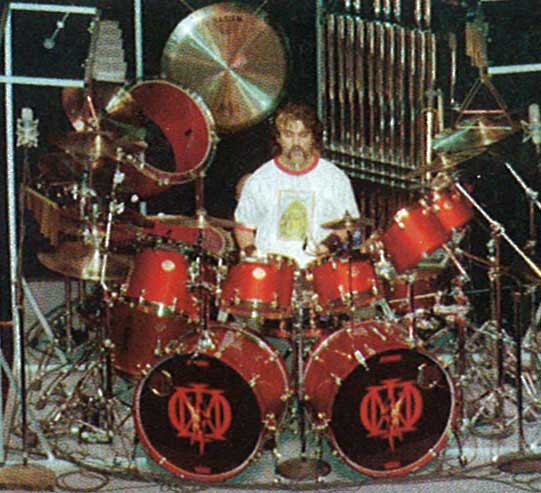

Rhythm: Can you talk about the evolution of your kit and your sound?

"Drumset evolution tends to be an organic piece by piece gathering, and I went through that just when we started pre-production. It's always a clean slate for me. 'Let's think about everything differently'. So I'd sit there looking at things and think, ' Wouldn't it be nice to shift stuff around and move this or that'. It's an opportunity. There's no reason a drumset has to look like this or that. But then I thought, 'Well, no, I like that there, or I want that cymbal there'. Everything wanted to be where it was and it had evolved that way for a reason. That's not to say I didn't re-examine every aspect of it and think about moving everything, and in some cases tried it. That part of it is natural growth. I had a timbale over there but it is valuable space. I guess in physical space you just make choices - what makes more sense and what is most valuable to you."

"I changed the whole set-up in 1994 when I was working with Freddie. I used to want everything right under me. I thought if I could have my whole body on top of everything it would make for better playing. Freddie said, 'No, your arm moves like this, put it where your arm goes!", and it all made sense, but what I had thought intuitively was cuckoo!"

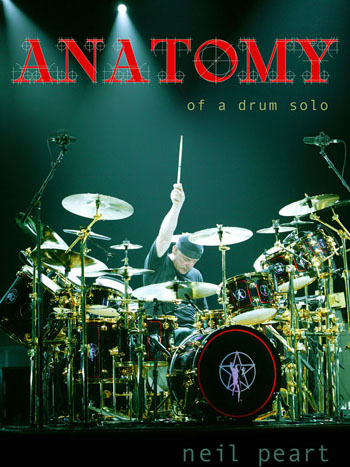

Mike Portnoy: Your latest DVD, Anatomy Of a Drum Solo, is another great opportunity to really give the fans a lot of insight to your musical roots, your drumming style and your creative thought process. Tell us a little about the making of this video...

"I had done A Work In Progress in 1995. I really wasn't sure what to do next. I thought about the next thing to do after taking on a recording and drum part arranging theme for the first one. I thought, 'Live performance is the next obvious one, but that's so huge'. So I thought, 'What about a little part of that, what about drum soloing?'. I had no idea of doing the whole concept and breaking it down like that. I began to develop the idea that there's a story in there - the story that the drum solo tells autobiographically and musical influences. All that becomes part of it. So I began to think that there is a story in there and a way to break it down in a way that might be illustrative and inspiring to other people, and I thought that the only thing really worth conveying is inspiration."

"There's a quote I used by Bob Dylan in my book where he was asked what art was all about. He said, 'The highest purpose of art is to inspire... What else can you do for anyone but inspire them?'. So I tried to put across in the video that this is where this came from, this is why it excites me, this is why I love to work with it night after night, and this is my way of constructing a solo, which I'm comfortable with as part of a Rush show and as a part of my expression, but also that it's not the only way of doing so, by any measure."