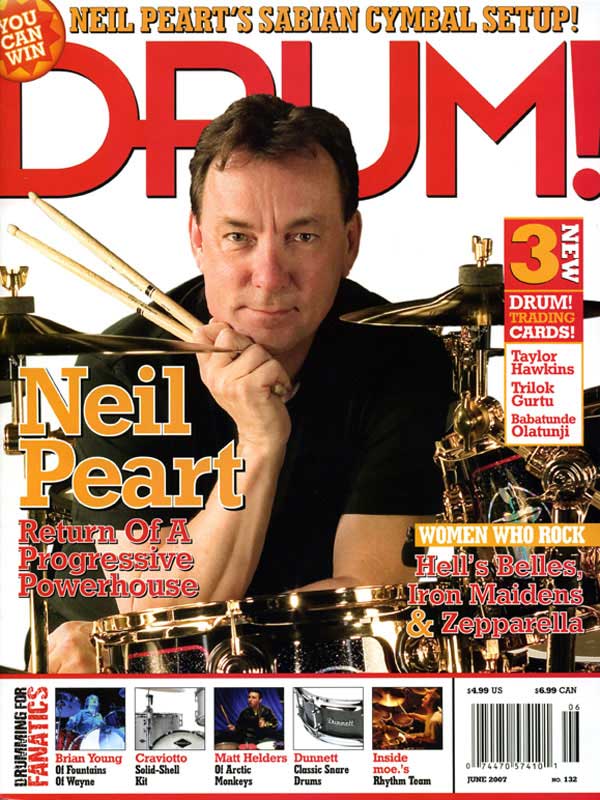

Neil Peart: Progressive Progress

By Tony Horkins, DRUM!, June 2007

If ever there was a player to make the stupid drummer joke redundant, it would be Neil Peart. Not 15 minutes into our conversation, he's already made a passing reference to evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin, quoted the eminent poet Robert Frost, talked about the influence of British science writer Richard Dawkins, and explained how he's worked the structure of the Malaysian pantun into his work. "Hey, did you hear about the drummer who finished high school?" Yes we did, and his name is Neil Peart.

Author, lyricist, motorcyclist and...oh yes, drummer, Peart, along with his Rush bandmates of the last 33 years, is set to release album number 18, Snakes & Arrows, and take the show on the road one more time. Thirty-five million albums since the band formed in the small community of Willowdale, outside of Toronto, it's back with a CD as vigorous and energetic as the records of its youth.

With the longest track tapping out at just over six-and-a-half minutes, and with two songs barely breaking two minutes, Snakes is Rush concise, lean, fighting, and fired-up. Many of the tracks follow traditional musical constructions with catchy choruses and almost-traceable verse/bridge/chorus formats, but there's still plenty of wild syncopation and implausible time signatures to placate the Rush faithful.

Secret To Longevity

With the bandmembers now well into their fifties - Peart turned 54 last September - Snakes presents a surprisingly youthful sounding Rush, a band still pushing itself to the limits of its technical ability. No small achievement. It's up there with being one of the few rare bands that has managed to maintain a stable lineup since its first record.

"You know, there really isn't a secret to that," says the soft-spoken Peart. "It's like any long-term relationship; there are so many accommodations that you make deliberately because the relationship is more important than some petty selfish interest on the day. Plus I like to use the word ?consensus' - democracy doesn't work if it's two voting against one."

Peart explains how he'd read that The Police flirted unsuccessfully with democracy, with the trio working itself into a corner, always leaving one member unhappy. "In our case we look for a consensus and will adjust arrangements, song parts, lyrics, cover art, running order ... the things that can be contentious. But we'll discuss them and discover where people's strongest feelings lie and try to find consensus within that polarity."

Perhaps the key to Rush's extraordinary longevity is that this isn't a process the band has grown into; it has been a way of life from the beginning. "I can remember in the early years, thinking about something I was upset or angry about and thinking, 'is this worth starting that kind of argument that can break up the band?' It takes a few straws and a few people drawing a line in the sand that they won't cross, and that's it. You can't go anywhere after an ultimatum. And again that's the same as any relationship: the ultimate thing to be avoided is the ultimatum. We don't even get close to that kind of stuff, honestly."

A Need For Feedback

Collaboration and consensus has been the cornerstone of Rush's success, and Peart's personal achievements. As the author of four books, he relies heavily on his editors and enjoys the interplay he has with them and how they force him to become a better writer. As a teacher, he works closely with his partners to produce the best instructional DVDs that he can. Similarly, the band - despite its clear ability to make records on its own - choose to work with a producer.

"We like to have a strong, respected person there with other ideas and other opinions and suggestions that we wouldn't necessarily think of," he explains. "Someone we respect that will help us establish that consensus. That's a really important part of the dynamic and although we've discussed producing ourselves after all these years, that's not really the answer for us."

For Snakes & Arrows, that person is 37-year-old Nick Raskulinecz, Dave Grohl's partner at his Northridge, California studio complex. A producer and engineer best known for his work with Foo Fighters, Velvet Revolver, System Of A Down, and Queens Of The Stone Age, Raskulinecz is also an ecstatic Rush fan.

"Generally we put out the feelers and collect show reels - a sampler of somebody's work - and there was something about the architecture of Nick's work that really stood out, especially in the way instruments were placed in the mix. Then when we met him we totally responded, and he listened to the songs we'd demoed like a fan would, with hands in the air and air drumming. He was all fired up and brash and full of strong ideas that we respected."

It turns out Raskulinecz had such an interesting way of expressing those ideas that he soon earned an onomatopoeic nickname. "When he'd suggest a part to me it would be, 'Blah-da-ba-blah-da-ba-broom-bap-booujze,'" Peart demonstrates, "so we ended up calling him Booujze. But that was what was so inspiring about working with him - he was that inside everybody's part. That's the immersion that he brought and he kicked us a little higher, urging that little bit more outrageousness out of us."

As an example, Peart tells the story of the album's first track and single, "Far Cry," a hard-rocking, super-melodic cut that Raskulinecz calls "the nearest to '70s sounding Rush."

"When we first played 'Far Cry' for Nick, there's this really intricate syncopated part at the beginning and end that took me hours to learn, and he's listening and says, 'Could you solo over that?' Of course the only answer from a drummer is, 'Yes, of course I can,' but I would never have suggested it. It's not the kind of way we would put ourselves forward, especially as Canadian guys."

In a mixing room at Ocean Way Studios on Hollywood Blvd., Raskulinecz's arms are flailing with considerable gusto as he gives DRUM! an exclusive playback of the nearly finished album and lives up to his nickname. Air drumming, air bass, air guitar, and air vocals come easy to the expert air-instrumentalist. With no small amount of enthusiasm he explains how in taking on the project he wanted to get back the feeling of an old Rush record. Peart, however, isn't quite so certain that this was the band's aim, or even what an old Rush record actually is.

"If we even thought about these things I'd be worried," he laughs. "You know - 'What did people used to like about us?' I see this happening with new bands, that sophomore album blues. Do you do what everybody said they liked or try to correct what people criticize? We really don't think that way. We write and play so much that it's instinctive and intuitive. Whatever we think is cool and exciting, that's what we play. We don't second-guess it - that's totally outside of our terms of engagement."

Not that it stopped Booujze from trying. "It was like a game - Nick would keep bringing up these forgotten mid-side album cuts from long ago and he knew them note for note. That was all very great but it didn't have anything to do with what we were doing. We wanted to do something fresh, and it was clear to me from the demos that we were already onto that. He wasn't going to tell us to write 'Tom Sawyer' again, but he had been a fan, and let's face it, there's nothing wrong with having this very knowledgeable, imaginative, productive fan in the studio when you're making a record."

Finding The Words

Long before Raskulinecz was even onboard for Snakes, Peart, singer/bassist Geddy Lee, and guitarist Alex Lifeson were busy laying down the album's foundations. At his home in California, the process for Peart, as always, started with the lyrics. "This time around I hit on a new thing inspired by Robert Frost's epitaph: 'I had a lover's quarrel with the world.' So some of my songs that were protest songs, I framed them like that, as if they were a relationship song between me and you, but in fact the 'you' is a whole bunch of people in the world that I don't happen to agree with."

Another recurring theme for the record is religion, inspired by the motorcycle tour Peart took when the band last toured the U.S. While Lee and Lifeson were busy enjoying the luxuries of the tour bus, Peart forged his own path, choosing to travel between shows on his motorbike. "I ended up collecting church signs and all those little inspirational - or admonishing - signs that are in front of them, especially in the mid-south. There's definitely a tsunami of religion that affects our side of the world and the Middle Eastern side of the world, so it's very topical in a way. But it became topical to me by observing it first hand, and, consequently, quite a few of the songs reflect that observation."

Peart also revisited lyrics he'd written 15 years ago, in particular a selection of ideas inspired by something he'd read in the front of his rhyming dictionary. "That's where I found a set of traditional forms and sonnets, and one was a Malaysian form called the pantun. Each stanza you take the second and fourth line and make them the first and third line of the next one, and they all have to resolve after five stanzas back to the first line. It's like doing a crossword puzzle, just as an exercise, and I never bothered handing them over to the guys. And then I was looking through them this year and thought maybe one of those would spark a musical echo. So there's a song on the album called 'The Larger Bowl,' where there's an arbitrary chorus but it's not, it's in fact the fifth verse."

Composing Parts

When Peart completes his lyrics he sends them to his bandmates in Toronto, who put together a basic backing track in their home studios to a drum machine. This demo is then sent back to Peart, who begins constructing drum parts around them. "One thing I like about working on demos separately is that I can just play everything, because there's nothing at stake," he says. "In the old days if we were all playing, you'd try as a drummer to lay down a foundation and then, as the other guys pulled their parts together, develop some interplay amongst them and maybe add your own decorations. But because I've got a demo just made with rough guitar, bass, and vocals to a drum machine, I just turn off that drum machine and try everything that might possibly work, and then eliminate the ridiculous, eliminate the impossible."

Surprisingly, especially considering the idiosyncrasies and complexity of the material, he resists notating his parts. "I try not to write it out, even on an instrumental like 'The Main Monkey Business,' which took me three days to learn. Instead I learned it by playing along until I found my place and found the transitions, and feels, and learned it as a piece of music. I want to play it until I feel it, and I have that luxury because I'm playing it basically by myself to those demos. I'll play it over and over, and at a certain point I'll go, 'I can beat that,' and I'll go out and do it again."

Peart pushes himself with dogged determination in an ongoing attempt to play to his strengths and eliminate his weaknesses. "I realize I'm a compositional-type drummer and I love to compose an intricate, carefully constructed part, learn it, and then play it. On the other hand, I've learned to compensate for that by not letting myself cement down every fill and arrange every cymbal crash and every transition. I want to keep it dangerous, not know exactly how I'm going to go into chorus three, for example. Given my natural instincts, the part could become too over-rehearsed and regimented, so I've learned to trick myself."

Cutting Basic Tracks

Once in the studio, Raskulinecz would also help the drummer push beyond his comfort zone. After they had the safety of a good take down - Peart would record four or five takes per song - the producer would send him back into the drum booth with a simple order: "Go out there and just go crazy."

"I realized that nothing is lost, that I had a good performance there, so if I went out and happened to do something in the course of that flail-through that was useful, then great. I can hear myself on this record when I just barely make it, but I love that. You can tell that guy has never played that figure before, and that's so exciting to me. Nick has that same instinct; he loves to catch me that fresh and raw."

Raskulinecz also pushed Peart to abandon his signature mega-kit and play a basic 4-piece on the instrumental track "Malignant Narcissism." "He was adamant about that," Peart laughs. "But to me it doesn't make any difference: if you have a bass drum, snare, and hi-hat, you can play a song. Add a couple of toms and some cymbals and you're laughing - I don't find that a limitation at all."

Technique Tune-Up

Peart has always been excited by fresh challenges, finding new ways of pushing his technique to the limits. Famously, in the early '90s, he decided to reinvent his style by hooking up with drum guru Freddie Gruber. "It was kind of a point of crises for me then, where I was able to play really precisely to click tracks and sequencers, but to me it felt so stiff that I was frustrated with it. It wasn't how I wanted to sound. I wanted that looseness. I want that feel thing. Just by chance Steve Smith introduced me to Freddie and I spent a week with him in New York and got some exercises and guidance from him. He's a guru kind of teacher - he's not going to teach you how to play a certain pattern or teach you a polyrhythm - he's more like a movement coach. "

One of the important things Gruber taught him was to "get off the head." "He said to just hit it and get out of the way - that's one of his dictums and I took it very much to heart. I realized the actual striking of the drum is only a tiny fraction of the whole motion: that stick goes up in the air, whips around, and then comes down and hits that drum for a microsecond. I learned to think about all the other stuff that was happening, and the bounce is a big part of that. Hit it as hard as you can, but by the time it's sounding you're off of it, you're somewhere else."

A byproduct of this technique is that Peart doesn't have to change heads nearly as often as he used to, ostensibly saving his endorsement company a small fortune. Bouncing as he does off the head, it's rare for any of them to become pitted. As a result, the majority of a single set of heads lasted the entire R30 Rush tour, and even in the studio for the recording of Snakes he barely changed a head.

What's more, Peart didn't use a barrage of snare drums to record Snakes. Where he would normally use six or more snares for different tones, he ended up using the same 14" x 5.5" drum for every track on the album - thanks in part to his new DW Vertical Shell Technology kit. "Normally the plies of a drum go around the circumference of the drum horizontally; John Good at DW started experimenting with running the grain vertically, top to bottom. When I first heard the difference I was in the factory and he just took two naked 13" tom shells, one done with the conventional grain, the other with the grain vertical, and just hit it with his hand: it was a full tone difference. It was just remarkable, the pitch that it had, and this was just the resonance of a piece of wood with nothing on it. I've used it on the album, and the snare drum is the most versatile snare drum I've ever had. I had all my other snare drums there but never for a moment felt a desire to try them."

On The Road

With album number 18 in the bag, the rest of Peart's year will be taken up with touring. Is he looking forward to it? "You're asking that on purpose!" he laughs after a long pause. "I have very mixed feelings about touring: I love the preparation, I love the rehearsing, and I like it for about a week - until we play a really good show. Then I figure 'Okay, the job is done.' Recording for me is the summit of what we do; touring, you're trying to work yourself to the perfect pitch of performance, and then do it every night 60 times. It can't possibly be as satisfying in that sense, but I find other ways to make it rewarding."

Which for Peart means heaving his beloved BMW bike onto the tour bus' trailer and getting the driver to pull over at a truck stop after the gig so he can hit the road. "I take off in some totally other direction, and if it's a show day get there before sound check, and if it's a day off I can go hundreds and hundreds of miles off our itinerary through all these little back roads. If you go on a conventional tour, every move is mapped out for you. I'm totally outside of that and I have no idea what's going to happen."

As for whether we'll see a 19th Rush album, again Peart is happiest not knowing what's going to happen. "I've really no idea, I'm glad to say. One year is enough of a future for me and this year is well mapped out already. I honestly have not given one moment's thought to anything beyond that. There's going to be so much to get through in preparing for and surviving this tour that I'll worry about the future later."

Geddy Lee: Musings On A Groove

By Diane Gershuny

Few marriages have endured as long as Rush's long-lasting partnership. Celebrating three decades together this year, Geddy Lee laughs when describing the musical chemistry that exists between he and Neil Peart. "It works simply because we've been playing together so long - and because we're both interested in being hyperactive and slightly obnoxious!" But in all seriousness, he explains how the pair have developed a shorthand, an intuitive sense of the way the other plays and knowing how to compliment that.

Their rapport, however, has not been a predictable one by any stretch. "A number of years ago Neil reinvented his style after studying with Freddie Gruber, and he took a very groove-oriented attitude to a lot of what he was doing," Lee remembers. "He was actually, in my view, playing a little softer even though he swears he was hitting harder and more accurately. That took some getting used to for me. At times, I loved that he could go into this circular groove that was a great addition to his ability to play groove-oriented stuff. But I kind of missed the old bombast - the fire in his old style of playing - where he would flip the sticks and smack the skins with the butt of the sticks."

But as Peart's style began to integrate a new set of influences, Lee's bass approach began to shift as well. "As he got more groove-oriented, that came simultaneously to my interest in writing our songs in a more groove-oriented way. And that was a transformation that started several albums ago - around Counterparts [1993] we stripped it back a bit. Although there was a different kind of groove starting to rear its head around Hold Your Fire ['87].

"We'd experimented on songs like "Scars" [Presto; '89] and "Red Sector A" [Grace Under Pressure; '84] to a certain degree, as well as on albums before that. Some of those songs were using electronics, electronic bass, to groove with the drums, whereas 'Animate' was the culmination of Neil's groove-oriented drumming and my more groove-oriented electric bass playing - together.

"I think he's evolved to a place where he can combine all of that and is a much more complete drummer now. He's got a light touch when he wants, he can groove when he wants, but he's also not afraid to pull out the old rock vibe and whack those tom-toms in a flurry! He can use all that he's learned from Freddie, and all the great strides he's made in playing a groove without, as Freddy would put it, 'laying down on it.' He's a total rock drummer."

Lee explains how Rush's songwriting approach has also evolved over the years. "Originally, songs were written largely on bass and acoustic guitar, and we came full-circle to that on this one. Alex and I would put the songs together, then Neil would work on his drum parts, and then there would be the back and forth as the parts would evolve.

"But this recording was more spontaneous. Whenever a song didn't feel dynamically like it was grooving, our producer would make us get away from the computerized performance-capturing and have it be more like three guys jamming. Just to have me playing live rather than playing to a part that I had maybe laid down to a click-track would suddenly elevate the whole rhythm section immensely. It would spark him and made a huge boost in the energy and spontaneous feel. I do think our evolution has been echoes of each other, and we definitely influence each other back and forth. I think it greatly benefited all the tracks on this album."

Dowels Of Glory!: Michael DF Lowe's Neil Peart Stick Collection

By Sabrina Crawford

In the world of Rush there are fans - and there are fans. You know the kind we're talking about - guys who've got "2112" tattooed on their backs, who carefully reconstruct Neil Peart-inspired zillion piece monster kits in their basements, and who devote years to mastering every Peart-perfect fill, lick for painstaking lick.

Guys like Michael DF Lowe. If Lowe - who's seen the prog demigods at least three times on every tour since 1974 - isn't the ultimate Rush fan and the ultimate Peart devote, we don't know who is.

Equal parts superfan and nerdy collector-genius, the small-town Texan has built a renowned collection of Peart's drum sticks over the last 20-plus years. "So many people think so highly of [Peart] it's like a rare diamond to have his stick," he says.

With 15 sticks touched by the master and well on his way to his goal - a complete set with one from every tour - Lowe still treasures the stick that started it all: A Rock-747 slapped into his hands by Peart himself backstage at a Dallas gig in 1981. "It was a Pro-Mark Rock-747 with his name on it," he says. "Back then, you couldn't get them anywhere else. If you wanted a stick with his name on it, it had to come from him."

Since then, Lowe's become a master sleuth, authenticating genuine articles and ferreting out fakes. And though he won't divulge trade secrets, he will say he looks closely for signature sanding and at the serial numbers.

Turning idol worship into a way of life, he's built a web site [neilpeartdrumsticks.com], helped debunk eBay counterfeits, and even helped Pro-Mark design commemorative black sparkle sticks to go with the 30th anniversary R30 kit. Though Peart's sticks can go for as much as $2,000 at charity auctions, Lowe's got no plans to sell. He just wants to keep sharing the love with fellow fans.

"These guys go nuts when I show them the sticks," he says. "It's like touching the Holy Grail."

And once this collection's complete? He hopes to gather a second unused set to give to Peart as a gift. And oh yeah, watch out Mike Portnoy - Lowe's also got his eye on you!

Disciples of Peart

"Neil Peart has been at the top of his craft for over 30 years. For someone like me, who was born ten years after Neil began his career with Rush, it is amazing he is still such a dominant, respected force. It is hard to identify many other drummers who have been performing at such a high level for so long."

Brandon Lanier

of QUIETDRIVE

"I like Neil Peart's attention to detail and precision. As fellow Canadians, Rush has been a staple in Canadian culture since I've been around. I was trying to learn 'YYZ' - which is named after Toronto's airport code - when everyone else had New Kids On The Block in their Walkmans."

Neil Sanderson

of THREE DAYS GRACE

"I think that pretty much anyone who has heard Neil play couldn't help but be influenced. His creativity and sheer athleticism are what made Rush one of my early loves as a music fan and air drummer before I ever decided to actually start playing."

Bryan Cox

of ALABAMA THUNDERPUSSY

"Neil Peart influenced me mainly by illustrating that the drums can be a foreground instrument in addition to laying down a groove and being supportive; that drum parts and fills can be a bigger part of the structure of a composition in a way that is dynamic, exciting, and cerebral."

Dave Brogan

of ALO

"My favorite performance is 'Tom Sawyer' from the album Moving Pictures. The transitions from 4/4 to 7/4 are seamless and the groove feels the same regardless of the meter. The drum fills after the guitar solo are totally on the money, and the energy with which he drives the song home always makes me wish they hadn't faded the track out."

Chris Higginbottom

of RUNNING STILL

"I really admire his drumming and strong songwriting skills. He writes a lot of lyrics for Rush, as I do with my band. I read somewhere that he started out on the piano and called it 'the inevitable childhood curse' I couldn't agree with him more!"

Mercedes Lander

of KITTIE

"I think Neil is so good that every drummer gets into a Neil Peart phase when they start playing because it is so intriguing and creative. We all hope to be that good someday. Then as time progresses we look at him as an amazing artist and a drum God that we can listen to and enjoy but never live up to."

Hayden Lamb

of RED

"My dad is a drummer, so from the beginning Rush was always on the radio. I always go back to my roots when I feel my playing has become stale, so Neil never goes very far without me replaying those blazing singlestroke rolls and remembering why I started playing my dad's old Slingerlands in the first place."

Dustin Schoenhoefer

of WALLS OF JERICHO

A Study In Control

Brad Schlueter

There are many great drummers in the world, yet few become legends in their own time. But with his precise technique, penchant for complexity, and monumental chops, Neil Peart long ago earned such a distinction. Admittedly, we aren't the first to put his drumming under the microscope, and we certainly won't be the last, but any feature story on Neil Peart is conspicuously incomplete without an analysis of his many contributions to the drumming vocabulary. So here are a handful of examples for you to savor, drawn from his back catalog, in addition to one selection from Rush's newest release, Snakes & Arrows.

"Lakeside Park"

From Caress Of Steel

This track reveals Peart's funky side and has a couple of impressive fills that are well worth checking out. The tune starts with a short fill that sets up the funky groove on the verses. About a minute into the tune Peart plays a cool fill that makes effective use of rests and his quick five-stroke rolls around the kit. A bit over the two-minute mark he offers another extended fill that, while very melodic, still manages to make good use of his quick singles. If these fills feel a little odd it could be the extra two beats that are tagged onto the end.

"Spirit Of Radio"

From Permanent Waves

This tune has one of those peculiar intros that has etched itself permanently into the psyches of drummers around the world. Peart plays this with a rubato feel against the strict guitar arpeggio, which imparts tension to the performance and makes its notation more challenging. The last couple of lines lead into the first verse and reveal one of Peart's favorite ride cymbal patterns, which is played 1 & ah (2) e & with the snare played on count 2.

"One Little Victory"

From Vapor Trails

This song has a great double bass intra in which Peart plays a funky snare pattern while playing quarter-notes on his second hi-hat over sixteenths with his feet.

"Far Cry"

From Snakes & Arrows

Here's the beginning of the first single, "Far Cry; off Rush's new album Snakes & Arrows. The song starts with a syncopated snare rhythm that almost sounds like it's in an odd meter, but isn't Peart plays some cool double bass fills that he mimics with his snare and crash cymbals. The sixth line finds him playing a two-handed sixteenthnote groove over one of his favorite bass and snare patterns. Keep your eyes and ears open for the occasional odd-meter measures that pop up at the end of the second, fourth, and seventh bars of this excerpt The last two lines show a cool groove that Peart plays with a RLRL sticking, voiced between his ride cymbal, open hi-hat and snare. He throws in quick double bass triplets underneath to keep it driving.

"Closer To The Heart"

From A Farewell To Kings

Here's an excerpt from the guitar solo that showcases a few of Peart's many cool fills. The first fill is a broken triplet figure of 1 ah 2 & 3 ah 4 & ah that he plays mainly on his snare, but also echoes on his toms for the second half. When Rush plays this live, Peart plays unison descending tom notes for the entire fill. The next figure begins with a sextuplet on the snare and is followed by a quick staggered rhythm down his toms. The third fill uses flamrned triplets on his snare and one of his high toms, and then is followed by descending tom flams on 3 ah (4) &. For the last one, he plays a tasteful eighth-note crescendo into the break.

"Grand Designs"

From Power Windows

The dramatic intro of this cut features a couple of massive sounding fills that lead into the song's unique verse. For that section, Peart plays upbeats on his splash cymbal to add an interesting twist to this up-tempo groove.