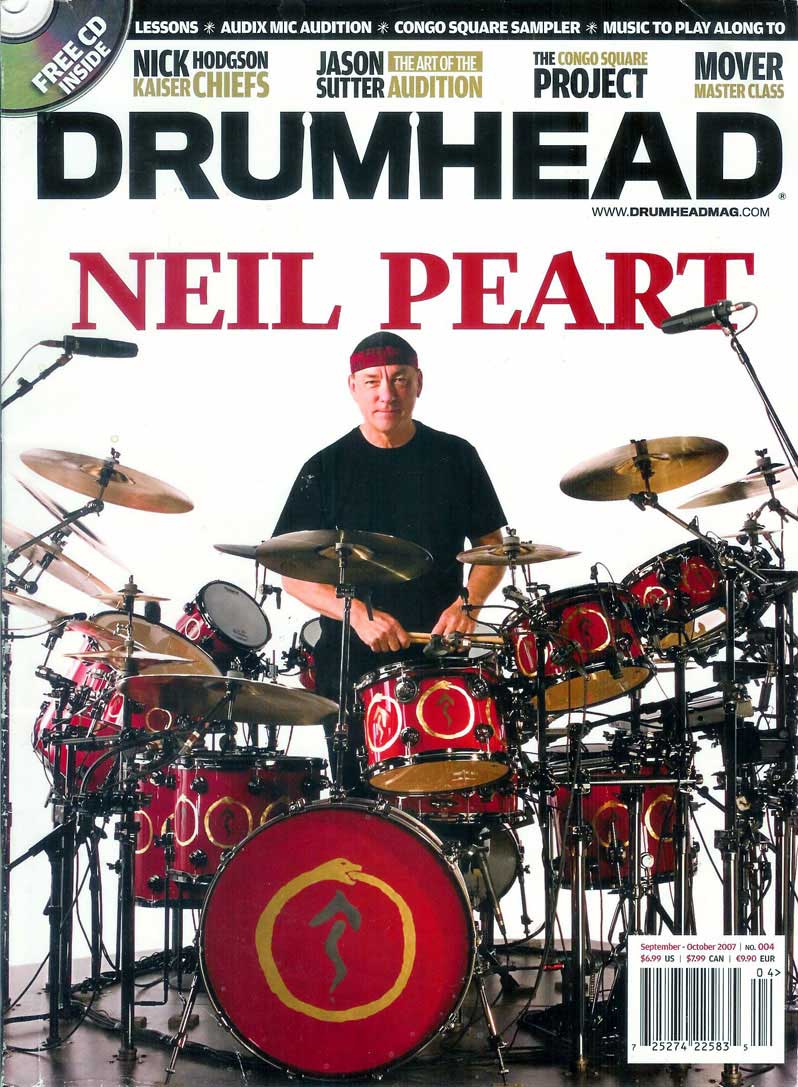

A Conversation With Neil Peart

By Jonathan Mover, Drumhead, September/October 2007, transcribed by pwrwindows

What do you ask one of the world's most popular drummers that hasn't already been asked? We all know what sticks he uses, what he listens to, what his hobbies are and every note of his drum solo.

Wondering what to base the interview on, I asked myself something instead. . . having listened to him for over 30 years and seen him perform for the first time that long ago, what was it that captured and kept my interest all this time? A simple question maybe, but not so easy to really put your finger on one specific thing. So I decided that we would have a conversation about certain aspects of his career that interest me: his drumming, his lyric and story writing, and his individuality.

A simple sit down; nothing prepared, nothing preconceived.

You've won a multitude of awards for everything from technique and instruction, to all-around drummer, and recorded performance. Many accolades! Personally, when I think of your playing, and this has been since I was quite young, the word that comes to my mind is: "fun."

[laughing] Ha, ha! Great, thank you!

And I can't say that about a lot of people.

That is so great! Thank you, and it's so true in ways, both light and dark, in a sense. Yeah, our barometer for judging the material that we're working on is: if we like it, if it's exciting to us. Again, it sounds so simple, but as you know, it doesn't usually work that way. And that's one thing that 's certainly contributed to our longevity and to our sense of companionship as people, as well as musicians - the respect of knowing that none of us is thinking cheaply. Everything is going to be the best we can do, something we haven't done before, better than it was. Nobody's ever considering the mercantile aspects of things too much. It's always about the music first, and based on, yes, the fact that we like what we're working on and want to work on it again. Like the main instrumental on Snakes & Arrows, "The Main Monkey Business," was the most re-written song of the whole thing, because yes, it's self-indulgent and certainly fun, you know in a muso way. But at the same time we were so difficult to please with it. We kept going over it and trying to balance up elements of texture, and I wanted more melody and I wanted more of a dramatic sweep and the stuff that I like in it. All of us had our own agendas for it that caused it to take weeks to write, weeks to arrange and, for me, days to learn it. The first time we played it for a musician friend, his first comment was, "How do you remember all of that?" [Laughing]

It's a lot in one tune.

I was tempted to cheat and write it out for once, because I learned notation when I first started sight reading and have never used it. It's like a language you learn in childhood, that kind of thing. So it slipped away, but I can still kind of trace my way, note by note. Yeah, that one and the beginning of "Far Cry" too, were just so slow and painstaking to learn by the ear-method, that I was almost tempted. But then, it's important for me to learn a piece. You know, when young drummers ask about playing in odd time, I say, "Try never to count. Learn to sing."

Right, learn it melodically. Much easier.

Yeah, and it becomes a song then. And all the parts, you know, it the guys drop a beat or add a beat here and there, for me, I don't count them, I just remember, "OK, the lilt of the song goes that way." Then it stays in my mind as kind of a pictograph of how it feels to play that piece, I guess, rather than thinking of it numerically. Even through the whole show now...of all these songs, rarely do I count. Once I count the other guys in, that's kind of how I play the song after that. There's a couple...that end section of "The Main Monkey Business" was just improvised and our co-producer, Nick Raskulinecz, every time I'd finished one of my composed drum parts, he'd say, "OK, go out and go wild now!" I'd say, "OK" and I'd go. I describe it like I try to lose my mind and stay in time. [Laughs] But I would gamely give it a try, and sometimes we did get those magic moments. And, of course, he just collected them. He's got a great ear and a great air drummer 's sense of drum dynamics and excitement and all that. And the kind of thing we agreed on so many times. Like I think we used one fade-out on the album. There had to be a crazy fill at the bottom of the fade, that's the kind of stuff that amused both of us, and I was glad about that. So I just ran through "Monkey Business" a few times, being as free as I could again-while remembering where I was in the song-and he kept recording them. Then he created that pastiche, and of course I wanted to perform it and learn it after that. So that was the hardest part - performance-wise - to learn that ending drum part, because I actually have to count.

I think odd time is easy for me because I grew up listening to a lot of progressive rock, Zappa, Crimson, Yes, Genesis, Jethro Tull, and even with the most difficult of that music-like Zappa and Tull-I found it quite simple to play because I was following the melody.

Beautiful. I'm astonished when I hear that. Doane's [Perry] a very good friend of mine. And Mark Craney's work is great too. Just listening to the two of them playing some of the Jethro Tull songs, again, "How do they remember that?"

Ian Anderson writes great melodies.

Yeah.

Speaking of the new CD Snakes & Arrows-and I hope you take this as a positive remark-this is the first time in a long time that, right away, I got the impression that you'd gone back to a bit of the older Rush. It's really great to hear, and for all the right reasons, it sounds really fresh and there's no loss of excitement or enthusiasm.

No, certainly not for us.

I think that's something so many bands that have 20 and 30 years behind them always try to do that and never quite make it. Like it's calculated.

No, and exactly, you've nailed the reason why: if it's calculated, it's not going to work. Not at all. The songs were written in an unorthodox manner for us, in that I live in California and Geddy [Lee] and Alex [Lifeson] live up in Toronto, so I was just sending them lyrics and they were working on them. Then finally we got together at my house in Quebec and exchanged feelings and criticisms and suggestions and all that. Then we got together in Toronto in May of last year and just spent the month working together. So even from the first time I heard "The Way The Wind Blows" and "Bravest Face," I'm listening to it as the lyricist and I'm listening as the drummer who has to learn it and maybe play it hundreds of times. But I'm also listening as a fan. I really wanna love that song. That's the ultimate barometer for all of us. If it doesn't sound too immodest to say so, we're fans of our music 'cause we make the music that we love. And yes, it falls short of our expectations. As Geddy once defined: "Mixing is the death of hope." When I look at the first record of ours that I consider to be definitive, it would be Moving Pictures - and it's so much the product of Permanent Waves before, and even Hemispheres before. All those things made it possible for us to make Moving Pictures. So I look back to the previous two, certainly Vapor Trails and back to Test For Echo. Test For Echo we took a turn, texturally, compositionally, arrangement, drumming-wise. I took a huge turn then. That was a key lynchpin. And Vapor Trails, of course, came out of a whole lot of chaos and turmoil, and that's reflected in the music. Even the sound of the music is interesting to me, but at the same time there's a linear thread that, in my drumming alone, I can see from Test For Echo. I was using an all traditional grip, using the right ends of the sticks, setting up my drums all different, I'd solidified that approach by Vapor Trails, and had gone back to matched grip and a more forthright, angular approach, because I tried to get away from that. I have a drummer friend, Marty Deller [FM], he and I compare notes that my drumming's very angular and I'm always trying to make it more fluid. His drumming is very fluid and he's always trying to make it more angular.

So, that reflects the path, but wanting something doesn't make it so. And it took all those experimentations, double bass drum work, stuff that I instituted in Test For Echo, because I had such facility on the drums after two years of practicing every day with lessons and inspiration and all that. And it took me places that then led me through, right up to this album. "One Little Victory" on Vapor Trails, for example, leads up to so much of the double bass drum work, but it's less disciplined. I found ways to make it smooth and flowing in rhythmic patterns, and now I can use it for fills freely without upsetting not only the tempo, but the lean of the rhythm.

You know, that's a hard thing. I remember talking to Dave Weckl about that years ago when he was recording "Mercy Mercy" for the Buddy Rich tribute. He was doing one figure where he came up on the double bass drums, and Steve Smith, who had been in the day before, and had done the same thing. The time would come up, not accelerating, but if he had a nice laid back feel going for example, it would straighten up for a moment. And I saw both of them go through that so, consequently, was made aware of it and wary of it, and probably avoided those kinds of figures for that reason until now. I've learned how, and it came through live performance. So, by the time it came to this album in "Far Cry" and in the closing song "We Hold On," I use all these kinds of double bass drum figures that only came about through that journey.

When I look at the history of Rush and your recordings, there's something I feel in A Farewell To Kings and Hemispheres as a pair, and in Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures as a pair. Does that make sense?

Yeah, could have been double albums.

But there's a big difference in the segue from the first two to the latter two, not only in your playing but also in your drum sound and approach to the kit. Did that have anything to do with you switching to Tama or was it moving from two-inch analog to the Sony digital machine?

Yeah, I'd have to say it was technological. Because when I listen to the old stuff, like the difference in Moving Pictures for instance, we made such strides in drum sounds at the time and microphone technology was improving. We were exploring even those PZMs [pressure zone microphones] taped to my chest. I said, "I want it to sound how it sounds [pointing to the middle of his chest] right here is what I was after. So we even experimented with that and mixed it into the ambience of things. It was the ramping up of technology at the time. And I'm a believer, although I have great nostalgia and romanticism for vintage stuff, I really think it gets better all the time.

Yes it does.

With this album I used the same snare drum for the whole recording, the new VLT one. From the moment I played it, its playability and sound were perfect for every song. On Vapor Trails, I used six different snare drums, you know, as I'm sure you do. I have an arsenal of probably 20 active snare drums that I have with me during pre-production, but this time from the moment I got that snare drum to this day, I have not touched another one because it's so great to play.

So the Slingerland has officially retired?

Yeah, it [VLT] just works. It's so versatile. Last night, the friend I was visiting has my Rogers drums, my first good set of drums that I must have got in mid '60s. He still looks after them for me. Grey ripple Rogers with the little Swivomatic tripod stands. I played them for a while last night too, and it was fun and all that, but everything is better now, I have to say.

Well, talking about things getting better and moving from era to era...

From error to error, [laughs].

You've got a wealth of material on analog and on digital. Do you feel that the opportunity of cutting and pasting and everything available in ProTools today is the proverbial can of worms, as opposed to a little hit of splicing and dicing tape? I see it all the time in the studio now where someone comes in and all of a sudden sees what they can do if they shift the snare drum 15 milliseconds here, and move a bass note there. All of a sudden it's a week of working on minute details.

Yeah, all that's possible. Even editing used to make me uneasy in the old days, but it was the best way to capture the best performances. And I know that a lot of great records have been made out of half of tape two and half of tape four.

Oh, you're being generous by saying half and half.

Well, you know what I'm saying. I've seen it in studios, where multi-tracks were going by that were just tape, splice, tape, splice, tape, splice, tape, splice. I would accept the reality if we had a 10-minute song and there were two or three takes to make it up. Then ok, fine. But mostly, even today, I like to feel that I can perform a good take every time, and then you look for something special, like when Nick Raskulinecz would send me out to go crazy. We were both looking for the seat-of-the-pants fills, and there are some on this where you can hear the rim shot as I just barely made it, and I just barely get back to 'one' and that's so exciting. It's not replicable. I do do so much preparation and play the songs over and over and over again, and make demos of them over and over again. But I've learned...again, my nature is to be so organized, so I trick myself and say, "You're not gonna fix that fill," or "You're not going to organize that series of figures." You've got these things that will work, whatever one comes out that day, that's got to be the one. I remember that "Resist," on Test For Echo, was one of the first times I tried to do that. I worked out all the different kinds of fills that would work, but wouldn't let myself organize them. So consequently, if I got through the first two thirds of the song and then made a mistake, we'd have to go back to the top. There was no patching or punching in, because it was a performance. It had to flow that way.

So, Nick's suggestion of doing that - of capturing a good take - gave me the satisfaction as a musician of having done the job right. I think it can be very undermining; there are two sides to that story. Yes, you can fix everything, but then the drummer feels, "Well, I didn't really have very much to do with that performance." So that, I think, has got to undermine your confidence, and your satisfaction in the work. And all of that intangible stuff is really important in the long term of how you feel about what you've done and the music you've made.

So I like to have all of that and then the delight of hearing something just so over the edge and so on the edge. You know, it gives me a smile. Then there are certain fills on this album and certain figures that I hear that I just have to smile, like, "I can't believe I got away with that!"

Unknowingly I think that's probably what I felt and what came across. A youthfulness you might say.

It is that exuberance. Yeah, you've got to be on the edge to produce that.

Well done.

Thank you.

With your studies and interest in always striving to play better, you went and explored traditional grip, the butt end got turned around to the regular way and you redesigned your kit after many years. I was wondering if you ever had the desire to go back to the older set up, and if so, would everything that you studied translate back to that kit, with the circular motion?

The basic geometry would change of course.

It wouldn't be based on the extended jazz kit anymore.

Yeah, really there's just no need to. Over the time I had two bass drums, I was always waiting for double pedals to get right. I just wanted that symmetry of the beats sounding equal. Of course people do use different size bass drums, like Terry Bozzio's setup. So, everything's legitimate and I'm the last person to draw rules, but I do find out what works for me. On the first day of pre-production, I do walk around my drums and go, "What can I change?" You know, what can I move? Can I change the cymbals around? Can I move some toms? Just to shake things up. I've done things like that and always consider the possibility, but there's always consequences. I considered every configuration and eventually I decided, no, after 40 years, this is the instrument that has evolved to suit my needs.

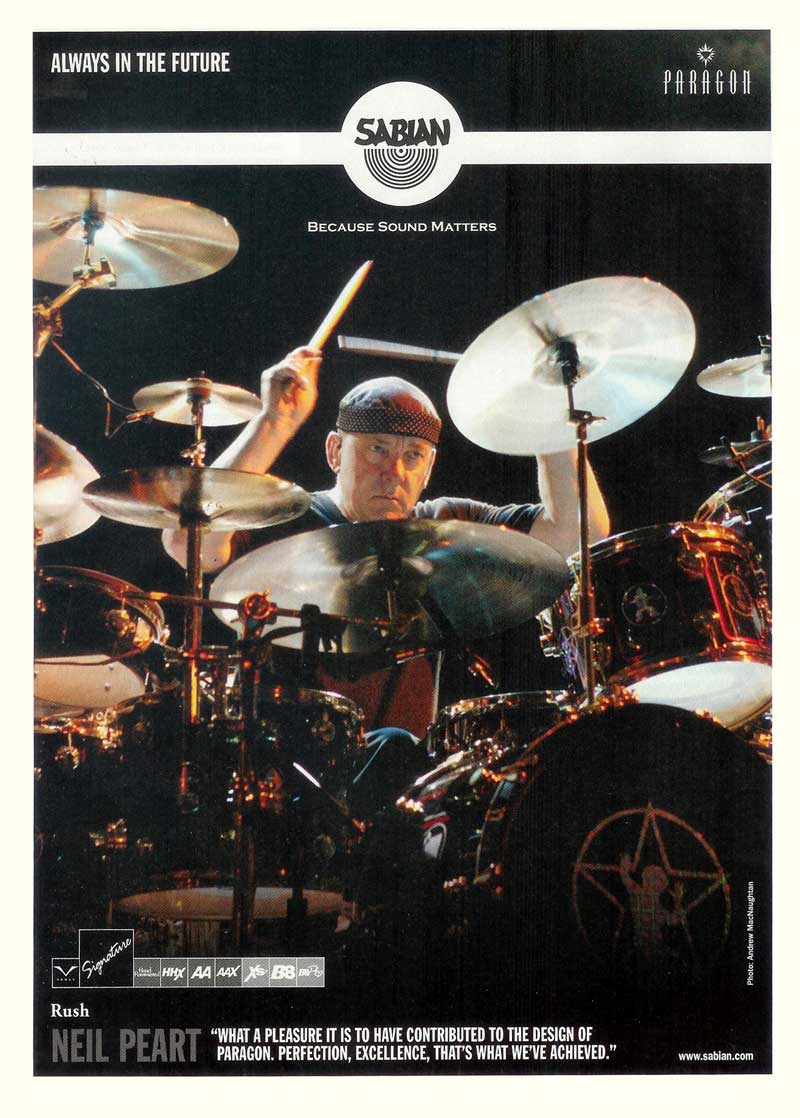

Even down to the specialization of working on the Paragon cymbals, and with John Goode at DW too...so innovative. I'm using a 23-inch bass drum. When we were opening shows in the early days, I would go out and hear other guys, and that 24-inch bass head just had a certain thud. But I never got along with them, playability-wise. I think all the time I've been in this band I used double-headed bass drums because I love the feel. And it even came up on this album where the engineer said, "Do you mind if we put a hole in your bass drum?" and I said "No, sorry you can't do that." 'Cause I love the playability and the dynamics and the full resonance of all that. So John said, "Well, what about a 23?" I was saying, "'Cause I love the playability of the 22." And sure enough, he tried it. That's why I love the craftsmanship that still endures there. John having that idea, and then the whole timbre thing is unbelievable, of changing the laminates and what that does, and now he's taken that to another place. Instead of just running the laminates vertically, he's starting to cross them and getting a lower fundamental pitch. And when DW built this live kit-which I haven't actually talked too much about yet-I had rehearsed for two weeks on the kit called my West Coast Recording Kit. So, until this kit was ready, I used that one for the first two weeks. Then in the same room we put up the new ones, and I could not believe the resonant size of each of the relative drums to its predecessor.

Different woods, different weights, different...

All those applications. He knows what I like for lower toms, with the shell having that fundamental tone. But the high toms I like to tune higher, because I like to hit them hard enough to de-tune them. I love the Simmons effect. So he knows that, and responds to that. I'm going to tune those drums way up above their fundamental, and then try, like a guitar player pulling a note into tune, to hit them hard to get the note that I want. He figures all that, with the reinforced hoops, and the angle on the bearing edge, which changes as the high toms go down. Again, more stuff than I understand what he does, but the result - the name of the game!

They sound like one machine now, rather than - these toms sound like this, and then I come to these toms that sound like that.

Yeah, that unity. Actually the first one I commented on was when he built the West Coast Kit. The unity of it as an instrument was greater than I'd ever had before. Yes, each individual drum sounded great, but the quality of their voice, ensemble-wise, was so rich. I just love how excited he gets about it too. That's such a pleasure to work with people like that. Mark Love at Sabian too. I was coming up with a new cymbal idea, on a couple of songs I could just hear this washy sort of ride with more than rivets. I remembered when we were kids, we used to buy a piece of chain from the hardware store and put it on our ride cymbal to emulate the rivet sound. So I described that to Mark Love and said, "You know what I'm after." Well, he came up with it, with tambourine jingles. And I ended up using it so much, because you get an almost imperceptible ride.

Well, they have the passion in their trade as you do in yours.

Yeah, yeah! And it's so exciting because he went through very painstaking efforts in producing prototype after prototype. I was trying to describe in words the sound I was hearing and you know that's not easy, especially when you're going in uncharted territories.

Have you ever been in a situation where you know that you've got the take and they're saying, "No, no, keep going. Let's try another."

I have a sense that starts right with the earliest demos, Alex will be my producer and we'll work together. I'll go over the songs and just play them and play them, and gradually start to refine it. I always have the sense if I can beat it. Then I'll go away and listen to it, and then the next night maybe I'll go back to that or move onto another song. But there's this process of leapfrogging, I guess, where I drag myself up to a bar and it's, "Ok, I can beat it."

In the studio, when it comes down to it, one thing I like about the way we recorded this time, is I DO like going to the studio for an official recording time and getting psyched up that little bit more. On the previous album, we were working in a little demo studio in Toronto. We just kind of adapted the demo studio and kept working and writing and we were doing everything at once: recording basic tracks, overdubs, writing new songs, all of that. And that was nice too, it's the only time we've ever done that. But all things considered, I really do like that little bit of pressure. It amps me up a little bit, and sometimes I do have that same feeling, I'll go out and do a take and think, "Ok, I can do better."

We were in Allaire Studios and the way we were set up, the control room was off to this side and I couldn't see Nick. I said, "I want to see you. Stand over there where I can see you." On one track he came out and drummed along with me in the room. I could tell by his response, even looking through the glass, he'd be all vibed up. So there's a barometer of excitement there, and a lot of times everybody knows. Everybody's around if we're doing the basic tracking together, everybody's there and everybody 's vibing off it or not, and I'll come in and it'll be like, "You got it!" And then maybe I'll go out and, do some rough and ready, crazy attempts at it, but a lot of times I think it's understood and that's the satisfaction aspect. I know there's always a take two. There's always a musical performance that maintains its integrity.

It's been captured.

Yeah. And for me, I can always feel like, yes, I can play that song. Even now, once I learn those bits of magic too, I can play them again and again in concert every night. So that just raises the bar a little bit more. And sometimes, yes, those accidents are hard to learn and hard to get your head around, but ultimately you can do it. Ultimately you can be satisfied by all that. So I think that's an important - and sometimes understated - ongoing part of your work, Obviously you have a body of work that you're proud of, and satisfied with, and it's something you wear all the time.

Well, that's interesting because although we both play progressive rock, not being a member of a band, I find myself in this day and age doing lots of sessions and ghost drumming. Most of the time I don't get credit, sometimes I do, but...

The Hal Blaine school.

Exactly. So, when I go into a session, I'm obviously there to work for the artist as well as the producer. But I always try, in a really subtle way, to slip in something that makes me happy about my playing on that record.

I totally understand.

You've got a catalog where you've done amazing things and you've gotten to explore so much, from tuned percussion and big drum set playing to different time signatures and electronics. What do you focus on to achieve when it comes to a new recording? You know, "This is something I want to get on this one that I didn't get on the last one?" Or do you not take that approach?

No, you know why? The example I've used before, but I think is very apt, is with the different experiences I've done with electronic drums and having them behind me as a separate satellite kit. I think it was around the time of our Counterparts album, I conceived the idea: wouldn't it be cool to have a whole set of foot triggers and congas, and to be able to play the most traditional drums, and then combine it with foot triggers and stuff to fill that out? So I had this all conceived, but the thing is, none of the songs needed that. [Laughs] So there's an example of where I had an agenda and I had this inspiration but it had no use. This also ties in what I was saying before about all my messing around with 3/4, and then suddenly, this album has so many songs and so many parts of songs that need that knowledge. That, to me, is almost a magical convergence. There's a kind of perceived synchronicity about it. The perfect example musically is me and the guys in the band. All of that, it's just like a convergence that almost seems impossible to be accidental, but apparently is.

Jamie Borden, the Las Vegas drummer, and I were saying one day that we thought drummers matured in their 50's. We were thinking about it and watching the mastery that Buddy [Rich] had in his 50's, of all styles of music; perfect technical facility and all that stuff. Then of course, at a certain age, you can't control it. It will start to decline. That's one thing that I'm grateful for now. At 54 years of age, we're playing a lot of very energetic music that was recorded when I was half this age and younger. To be able to play not only as well as I did then, but better, you know? I have more speed and more power and more control over the time, and that's the most gratifying thing. You'll know from doing so much session work, when you gain control of the click, and you can push and pull that thing all over the shop and still make it feel good. That's a recent breakthrough for me. And in live performance now too, I feel a more relaxed confidence about time-keeping. This is new to me. Feeling that confidence and feeling that technical freedom of being able to do that level of independence, with the confidence of doing it in time. Technique is a hard-won thing in itself and so is time-keeping, and I think at best they're parallel paths. I've tried to point out to people, a simple thing in the hands of a master is... you know, when you hear Steve Gadd play a simple rhythm, you could not write that down. When you hear some guy who 's been playing for six months say, "Well, I can play that." Oh no you can't! [Laughs] Please don't! But that's a distinction that, of course, only maturity can give you, and if you can keep the stamina. That's the great thing about drumming, it's stamina rather than sprint. I think we've done two tours in the last five years. That's a lot of live playing at the very highest level you have on any given night: mentally and physically. And it has to be good for your game. As tiresome as it does become to me, I must admit, at the same time the results are measurable. The cumulative effect of all that discipline and all that application and all that exploration - really important elements of live performances - they add up to something in the end, unexpectedly, because it's a slow evolution that you can't measure. You can't say, "Look I can do this better than I could do yesterday!"

It's got to happen when it happens.

Yeah. And I only, honestly, started to feel that as I was rehearsing for this tour. Somehow for me, it has been a realization. Making the whole of the last record and pushing myself in compositional and in performance ways, and feeling a new understanding of time sense.

That's the type of thing you get with time and experience.

You can name all those kinds of drummers I can always use as milestone of maturity. Like, when did I understand Mel Lewis and what he was about? Another guy I was thinking of the other day too, Sam Woodyard, with Duke Ellington on that wonderful Ellington/Sinatra album. The drumming is so clich?, but in the pocket, so graceful, so eloquent. Again these kinds of words are the only ways to describe the subtleties of a musical master like that, but it takes a certain maturity and experience. You have to learn how hard that is too. So, it's not just maturity and growing up and growing old and acquiring sophistication, hut it's trying it yourself, and learning how difficult it is to lay the time that way.

It's the old saying that it's more important to get to the point of knowing what not to play as opposed to what to play.

I never learned that, [laughs].

We all go through that phase of, "What can I play here? What can I play there?"

Yeah.

Speaking of Gadd before, the space in between his quarter notes...

Unbelievable. When he did "Love For Sale" on the Buddy Tribute, he's playing this quarter note, and it's all implied! That was a big lesson to me actually. I listened and thought, "Why does that feel so good?" That became my favorite song of all the stuff we recorded. I just listened to it, over and over again. I watched him play that. I sat in the studio for every drummer, right beside them, and listened and watched and immersed myself in their performances. Just sitting there thinking, "That shouldn't feel so good!" You know, he's just going ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding. But oh boy! Funny, when I did the Buddy Rich Tribute Concert before that and I was showing the guys in the band, they were watching Gadd, and Geddy says, "He plays from his ass!" [Laughs] Well, yeah. He DOES!

I remember reading that Keith Moon was such a big influence on you in the very beginning that when you went into your audition for Rush, you were playing like Keith Moon. I listen to Fly By Night and think, what happened between the audition and the recording?

No I wasn't. That's a bit of a misinterpretation too. I wasn't playing like Keith Moon at the time. But the person who recommended me to the guys had said, "Oh, he plays like Keith." But I didn't.

The other anecdote that I often tell is that when I first got into cover bands that played Who songs, I discovered I didn't like playing like Keith Moon. That was the important lesson that I learned, and I preferred a more compositional and organized...just as your playing should be a reflection of your nature, so mine is. The more technique, understanding and experience I gather, it allows me better to express what I find exciting in drumming, and what I think works well musically and dynamically. Those things, they're choices that are made, at best, from your heart, from your character. Although at its height, what Keith played on Tommy for example, is just sublime musicality, and so beautifully musical on that album in particular that I'm still impressed when I listen to it. I still understand what I saw and heard in those days, and why I so love his approach to playing the drums.

Did you get the re-mastered full-length version of Live At Leeds?

Yes, Lorne [Neil's drum tech] got it for me.

Wow! I never knew how well he played that night, certainly not from the original recording.

Yeah, that's what can be surprising, is how good he could be. I play to the lyrics and the vocals. If there's a song with words that someone is singing, that's generally considered a fairly important part of the song. So, as the drummer, of course, you should be responsive to it, I saw the making of Who's Next one time and Roger Daltrey sat behind the console and just brought up a solo of the drums and then the vocals and pointed out how Keith was so locked with the vocal phrasings and punching them up and framing them and all that. That was another thing that I must have sensed then and incorporated it in my playing so much, without knowing. Listening to his fills and his sense of playing the music, all of that, I would have a different, deeper response, that I can better understand now when I listen to it. Yeah, when Keith was at his best, he was just so musical and the time, for all the chaos and wildness of his playing...

Was pretty solid.

Yeah! It was so musical and he just had a sense of what it should be, and it was remarkably good, And unlike a lot of us, he didn't play fast. But yeah, those are lessons that I guess I absorbed from Keith Moon along the way. Other people have remarked on that too, "I can't believe you talk about Keith Moon all the time. You play nothing like him." And I say, "Well listen to this," and I'll play certain figures, "That's a Keith Moon Figure. That's exactly what he would do." And those are ways I find to use them. Yes, the context is totally different and my intent is totally different, but it doesn't mean I haven't learned and incorporated it all.

Is this a good time to take a pause and do the drum solo?

Absolutely, let's go.

"And now, ladies and gentlemen, the professor on the drum kit..."

It's 5:00 p.m. and time to take a run through of my solo and get all the programming organized. A friend of mine made a film to accompany the outro I do. I did "One O'clock Jump" for the last couple of solos. Of course, one thing about the DVD age is, everyone has seen our whole show inside out, so we felt compelled to change everything as much musically as we could, and completely visually. So all the movies from start to finish are all brand new, and the same thing with my solo. While I still like it, and it still serves me as a vehicle of exploration and all, every tour, I never want to change, because it's what I arrived at, and I could still keep growing from there. It's amazing what a little laboratory it is for me. But I felt compelled.

So I started thinking, and it took me to some beautiful places, and I'm glad I make myself do that kind of stuff. Because previously, "The Drum Also Waltzes" was one of the main parts of my solo, and it's taken me to so many places. I thought, well I want to keep that in a way, and I want another kind of ostinato like that, and take it to another place. I remembered a 4-pattern that I used to do that is so similar to that, based on the hi-hat. So, it's still like that, but it changes at the 4, and suddenly I found I was so free. All the research that I've done on 3/4 over these many years served in the same way, I could play any tempo, any time signature over this and it was a revelation. But it's also one of those pulses that I couldn't get into it every day. I started working on solos over a month ago, running over it in my head, as well as during the rehearsal time. Some days I couldn't nail that thing, you know? And there are little rhythmic tricks, though all of us probably have different ones, that, like with language, there are certain words that people just can't pronounce or can't spell. I think drum figures can be like that too, one day you'll know how to spell that word, and the next day you won't; Likewise with a figure like that. So I just kept working on it and working on it, and once I did get over that barrier, it was such a beautiful sense of accomplishment. I've said so many times that the 3/4 stuff was just for me, I couldn't imagine there'd ever be a use for being able to play 3/4 on my feet and 7/8 in my hands. But it was interesting every night during my solo and during the shows, it was a secret satisfaction for me.

And sure enough, when we went to start working on the songs for Snakes And Arrows many of them were in 3. Suddenly I was using exactly all that stuff. In "The Way The Wind Blows" the tom bridges and the ride cymbal pattern through it, are exactly that pulse, that "Drum Also Waltzes" thing that I'd been doing for so long. So, having completed that circle as it were, it's really exciting now to find a new avenue, and then to only think afterwards how similar my 4/4 pattern is to the 3/4 pattern, and consequently I have a similar amount of facility and freedom with it. So, that's an example of the kind of the circle that's come around. I wanted to keep the 3/4 stuff too, 'cause I still love that lilt, so I put it into an ethnic section, as you'll hear when I run through it, and have keyboard percussion just playing long sustained chords while I go around tablas and a Zulu drum and a shaker and stuff. So I do the 3/4 "boom-shh-shh" with shaker, and then play samples on top of it. And an industrial thing, which I've never actually done. I'm bringing back techno, bringing back industrial sounds, 'cause it's something I never really used, so all of that became pieces of it, and I'm trying as hard as I can to make it improvisational. I talked so much on "Anatomy Of A Drum Solo" about being so choreographed and architectural about it, so I thought, "Well, I'm not going to do any of that anymore," alter having stated that as my whole nature of being, and my nature as a drummer too.

It's a late realization for me, and maybe I'm last to know - to think of myself as a compositional drummer, and not so much as improvisational. It is much more my strength to be able to organize a part musically. Take a song like "Tom Sawyer," it's still right to me. I'm still quite so happy to play it exactly like that. It's always hard. It's always challenging, if I get it right. So, that's been my kind of modus operandi all these years - to make up a really good part then try to play it as well as I can every time. You know, it's simple, but not so simple, of course.

Likewise with the solo, where I would put together frameworks that were relatively improvisational, if I felt up to it on a given night, but would keep a standard of quality from night to night too, given the frailties of us humans and us drummers. I noticed, and pointed it out on "Anatomy Of A Drum Solo," there were two solos, a few nights apart; one from Frankfurt, one from Hamburg. I'd been talking about the ways they can vary from night to night and those two were incredibly classic examples where I started the "Waltz" section on the high toms one night and low toms the next night. The whole fluidity of that night in Hamburg was totally different from the feel of Frankfurt a few nights earlier. So those are all pointers to me.

But so far, as I've said, I've been playing the solo for a month or so and I still haven't nailed it down. I have a framework so that Lorne, my drum tech, knows when to change programs, and when to turn the riser and all that. I gave him cues, but I have not cemented down any of the parts. The whole big band section I wanted to keep because I love it so much, it's kind of a trademark, but I didn't want to do "One O'clock Jump" anymore. So I got "Cottontail" from the first Buddy tribute that I did, took the end section of that, and then took horn sections from that song too. The horn sections that I usually improvise and riff on have been from just generic big band shots in the past. This time I got our guy to take them right from that song. So they'll have a certain character that, even though I'm playing totally different tempo and feel and dynamics, it all leads into "Cottontail" so much nicer. You know how when you're working on something like that, you're lying in bed thinking about it, how you can get from one part to the next part and then potential variations. I kept thinking, "I haven't got the cowbells in there yet. I've gotta get the cowbells in!" 'Cause they're always just the goofy moment in the solo. No matter how bombastic and intense it gets, as soon as I go to those cowbells it's like [snickers] and, you know... that's a good thing.

I like to come in in the afternoon and do the solo as kind of my warm up sound check. I haven't even decided if I should start with the snares off or the snares on, I'm trying to leave that open. Just to see what comes out on the night.

Thanks for the sneak preview. In a way, I'm reliving some of my childhood.

Yeah, me too.

Speaking of childhood, how about some nostalgia. In 1978, at the Music Hall in Boston, for the Farewell To Kings Tour; my second time seeing you guys. You were onstage, full throttle, in the middle of "Xanadu," and all of a sudden, all of the power goes out onstage. You didn't realize, even for a moment, that Geddy and Alex had stopped playing, and you just kept on going.

Maybe I was just covering up?

Do you remember the gig?

No. But what do you do? You keep playing.

That's when you realize the difference between acoustic and electric.

Yeah.

Here's another one. In 1982, I had already been to London and played around a bit. I was back in the States to record Punky Meadows' first solo record, which by the way, Terry Bozzio doesn't need to know [laughing]. Anyway, I did the recording and then got a call from England, asking if I'd be interested in auditioning for a band called Marillion. Next thing I know, I'm down in New York City to meet them while they opened for you at Radio City.

That's just before we recorded Grace Under Pressure because we played several of those songs, and I just added the rear drum kit, but the riser didn't spin. We did "Red Sector A" and I just played it facing the back of the stage.

I don't know if you watched them at all, but they got booed off the stage every night. The lead singer, Fish, was all done up in grease paint and the people didn't get it.

Right. They were big in Quebec though.

Well, a couple of weeks later, I flew over to London, auditioned and I got the gig.

Ok, that might be where your name stuck with me. 'Cause I did like them. And their drummer, previous to you, was the guy who played on Propaganda I think.

Ian Mosely. He was after me. We auditioned at the same time and I ended up getting the gig. Then when things didn't work out personally between Fish and myself, I split and they called him. But the synchronicity here and the strange circumstances...

Yeah. I love all those.

Me too. So I get the gig on a Wednesday, fly to Germany on Thursday, do a live recording on Friday and then a week later, I'm in Rockfield Studios.

With the sheep. [Laughing]

Yep, and I'm saying to myself, "Wow, this is the place where they did A Farewell To Kings and Hemispheres. It was amazing to feel that! And it happened to me again a few years later, the first time I played Massey Hall [Toronto]... "Wow, this was where All The World's A Stage was recorded."

Yeah, Ghosts.

Funny you should say. This is the craziest thing. In the middle of gig, the string broke off my snare strainer. Correct me if I'm wrong, but during "2112" on All The World's A Stage...

Yeah, the take we used...I was so f ----- g mad.

Your snare drum too!

Yeah. There's so much anger in that 'cause it happened three times, and I was so mad. I didn't even have a drum tech in those days. It was like one of the backline guys helped out with drums. Our front-of-house engineer at the time set up the drums, but he wasn't there, and there was no one there. There was so much fire in that take that we said, "Use it anyway."

Anybody ever pick that out and tell you about it?

No, not lately. [Laughs]

I remember as a kid being so excited when I realized, "Ah, I think the snare let go." And there I am in Massey Hall 15 years later and the same thing happened.

Don't ya hate that?

No, actually, I really liked it. I felt...kind of privileged and honored, because it happened to me too.

It was the same ghost, the same gremlin.

A lot of people look up to you for insight and wisdom, and your points of view on all sorts of things. Politics and religious dogma aside, any thoughts on the world as it is today, post 9/11?

Yeah. Snakes & Arrows is kind of my commentary on all that. Part of the musical heritage of this record was having done two tours since the last album and being in such great playing shape as a band, and as individuals at the same time. I traveled both of those tours by motorcycle and choose the back roads and choose the small towns, and the rural routes and all of that then formed my picture of this country and of Europe so much. I wrote a book about that tour called Road Show. After traveling through the heartland of the Evangelical Christians, I was just jotting down the church signs and all that just for kind of entertainment and humor. Then at a certain point I went, "Wait a minute. Stop! I can't just report any more, I've got to editorialize." And that's the fine line in trying to work in prose writings and certainly in lyrics too. I'm actually trying to observe a little bit and editorialize a little bit, but combine the two in a way that allows other people's interpretations.

But yeah, the lyrics of Snakes & Arrows certainly, that ties so much in with Road Show. Then it became further compressed into the more distilled expression that lyrics are. They're the least words, but the hardest to write, by far. But at the same time, you can distill down into images and make those observations of yours visual, That's the part of what makes verse and what makes lyrics - making them images and metaphors and all those little tricks of that trade. So, it's a further opportunity to express myself. In the broader terms of what you're asking, that's where that information is: in the book and in the songs.

Does it matter to you at all, either melodically or rhythmically, what happens to your lyrics when you hand them over to Geddy? Have you ever not liked what he's done with them?

There are always times when you say, "Well, I love what you're going for here in this part, but maybe that part could be better." At this point I just give Geddy a whole bunch of stuff and he's picking and choosing, and sometimes I'll fill a page with words and only two verses will get used. Still, those two verses got used, so I'm not disappointed, I'm excited. And I'll take those and I'll build on them and he'll say, "Well, if I could just have two lines like this, and maybe another verse like this and I'm gonna make that the chorus and all that," and I'm like, "Ok, ok," but enthused because he liked it enough to sing it and it's going to be used. That to me is just inspiring more than anything. I run off to make all those changes.

So, yes there are responses to things that are immediately like, "Yes!" And immediately like, "Great, but could be better." Like my book editor, I describe his approach as critical enthusiasm. We always are careful with each other's ideas to be respectful, you know. You can't go, "That sucks!" You can't maintain a 33-year relationship, or any kind of a relationship in life, by being coldly critical. You have to be enthusiastic and supportive too, as we always are with each other.

Or casually evasive.

Oh yeah. If there's something you're not crazy about, just be quiet and maybe somebody else will say something...or maybe you can find a way to make that more to your liking. Yeah, there are all kinds of diplomatic ways to go about getting what you want-and also consensus. I described it to people: you can't run a band, even of three, on a democracy, because you're going to have one unhappy person. And that's not good, so we find a way that gives all of us a sense of consensus, that we've all been involved in it, and we've made the best possible deal. If I want a certain song to open and the other guys want another song to open, then we settle on one we can all agree on and go with it, and stop the fight.

There are so many things that are worth arguing about to me, that are important to me. Lyrics are a good example. If Geddy comes back with scraps that don't add up to something, then I go crazy. Because they can be impressionistic and even abstract, but they have to have an internal meaning to me. There has to be some internal logic that makes them hang together.

Alex and Geddy are the music, you're the lyrics. Have you never come up with a drum part that they heard and said, "we're going to write something to that?"

No, it's more the opposite really. Alex is such a creative drum machine programmer and he does the programming for them. It's like, I need a quiet place over there to work on my own and the two of them, they have a drum machine. That's fine. So it's a good balance of things such that, no, I would say, there hasn't been a time when the drumming has been the direct influence for the music.

When you choose to write about something in particular, whether it's based on Rand, or Jung, or Greek mythology, are you writing about it because it's your interest and your love, or because you want to espouse that to somebody?

It's something that has to be said sometimes, and I've often said, one of the strongest inspirations is anger. You know, being so mad that you've just got to say something. I wrote the song "Second Nature." "I know prefect's not for real, I thought we might get closer. But I'm ready to make a deal." In other words, ok if we can't get perfect, then let's get better. So, in all those cases there are things that I really want to express or describe or evoke too. That's another thing that crosses over into prose writing: when I'm describing something, it's not an inner thing. I want people to see this the way I saw it. That's one of the things that I learned in prose and have applied to drumming too - what does the reader need to know to go where I want to take them. What do I have to say, what words can I use and in what order to express that. How can I set up images that will clarify this without it being a sledgehammer, but at the same time not being a pussy. [Laughs]

Does that come into play? Are you choosing songs because of a lyric you want to convey?

No, it's definitely musical. Absolutely. The last tour was a really long show of all old material. It was our 30th anniversary tour and we deliberately did a hugely expansive retrospective. So we felt liberated that we'd done honor to those songs and honor to the fans on the last two tours. We've done so much old stuff, and we felt, well, we don't have to this time. We're doing nine new songs, which is unheard of, plus we dragged back songs from the past that we either haven't played for many years or, in one case, there's a song on Permanent Waves called "Entre Nous" that we never played live, so we brought it out for this tour. There's a song called "Mission" from the mid-80s that we really loved and hadn't played for a long time. It's so great to play, and it's got a keyboard percussion, marimba part in the middle. It's got a part in 5. It's got some straight ahead 4/4, really nice tom fills, and all this and I was like, "Yeah, great!" It's so great to revive that and feel it again, why you loved that song. But the choosing...I'm a bit conscious of lyrical content and running order, for example, of what I want the statement to be.

And on the record?

Yeah. That's where I might be swayed towards wanting a certain song to lead more than others. In concert, it's another instinct of presentation and pacing. Like, I make the walk-in music. I've always done that for our concerts; the music between sets or between bands in the old days, or whatever. When the three of us are talking about the songs we want to play, or don't want to play, if somebody really doesn't want to play a song, we don't do it. 'Cause you're not going to go out there 60 times and force somebody to do something they don 't want, or play a song they lost the spark for. I remember there was one tour, maybe in the early '80s, where we were sick of "The Spirit Of Radio" and dropped it for half a tour. You know, one of our most popular songs, but all of us felt, "eh." Then we brought it back again - that was 15 years ago at least, and we've never dropped it again. But for those few months we just had to put that one aside no matter what. And it can be as simple and as seemingly off-the-cuff as that, but there's always due respect to the music, and again we are fans of our music in a modest sense, so we get excited. But it's also for the audience, because that same reference and that same relationship that exists between us and our music, hopefully exists between an ideal fan and our music. You kind of think you're speaking for them and feeling for them when you choose the songs.

As a drummer who's always growing, studying and advancing, you can't help but look back on your past catalog and always critique yourself. You know, "I should have done that better," or "I wonder how Gadd would have played it?" Do you ever look back as a lyricist and think "How could I have written that line?" or wish you had chosen a different word to have gotten something across better?

Well, I'm glad to know I could have done it better now, God, how awful would it be if that were not the case. The same thing I was saying about going out and playing live this time and feeling like I can play faster, stronger, better than I could 20 years ago, never mind two years ago. If I didn't listen to stuff from the past and wince a little, then I wouldn't have gotten better, and I wouldn't understand that I know more now than I knew then. I'm actually glad about that.

There's a good parallel there with book publishing. I worked on it for 20 years before I published a book. I'd already privately published five books and worked on all kinds of prose writing to learn the craft. By the time I did publish my first book, I can still live with it. You know it has excesses, but it definitely captures the kaleidoscopic madness of Africa. When I had to re-read it a couple of years ago when we had to do a new edition, it was like, this is over the top, but it's true. This is what it felt like to be there. That's great. When I read the previous ones that I didn't publish, I was so glad. I wish I had that in music. That's kind of how I feel about it, but at the same time, it's out there. Yeah, there is stuff I would expunge from the record, given a choice, but there's nothing I want to go back and do again. I've kind of outgrown it all. Like "Tom Sawyer," I'm still glad to play it every night 'cause it's still fun and hard and challenging and satisfying and all that stuff, but I have no desire to go back and revisit it. One of the reasons that drove me to study was a growing dissatisfaction with my time sense. Working so much with clicks and sequencers in those days, in the '80s going into the early '90s, I had developed a metronomic time, but unfortunately it was metronomic. It felt so stiff and it wasn't what I wanted to hear. Then I met with Freddy [Gruber] several times and talked with him and just got curious. You know, I wondered what it would be like after all these years to work with somebody like that. So, I made it happen and of course, it was completely transformative in ways I could never have predicted at the time. You can't measure the change that makes, and the impact that makes on you inside, to have transformed everything. That's the beautiful reward from that discipline, from that application of stuff. There I was doing that after having played for 30 years, and being in my 40s with a family and all that stuff, still finding the focus and discipline, saying, "I'm going to practice every day." Then the band talked about getting back to work, because we had taken a pause when Geddy and his wife had a baby. I said, "Guys, I'm not ready. I need another six months to really do this thing that I set out to do." Then we started working on Test For Echo after that. The fact that I practiced had so many waves and ramifications; all that time had a cumulative effect that a decade later now has added up to so much that couldn't have been perceived. Making a whole record with a traditional grip was an experiment, but I eventually decided a matched grip is better for me in the way that I want to express myself and the music I want to play in this band. But I'm so glad I did it. I did all that stuff. I played hard rock with traditional grip.

Not an easy task.

Yeah, so all of that was good and it gave me a facility now where I can do that. I was telling the sound engineer on that tour that I was worried about the strength of playing and having the big backbeat. I said, "I hope you're getting as good a sound from the traditional grip as you are from the matched? He said, "It's better." He claimed that the songs that I played with traditional grip, if I just laid down on the rim just right, it got a fatter sound than it did when I played with matched.

Tell me if I'm mistaken but back in '78, you did that in the guitar solo section of "A Farewell To Kings" and switched over to traditional grip.

Yeah. I think so. There are certain figures I only learned 'cause when I first started with drum lessons I had a practice pad and a pair of sticks and my teacher taught me traditional. The pillow, Mom and Dad, and paradiddles. Having learned those so painstakingly, I wasn't about to go back and waste time relearning something. So for rudimental stuff I always switch back, even in those days, it was a given. I've started to be able to play paradiddles with matched grip, but I don't think I'll ever be able to play a good double stroke matched. Given time, I could, but I wouldn't give the time. Why should I? I can play a satisfying double stroke with a traditional grip, so why? I love doing paradiddles now with both hands. And I've just started to stumble over a frontier. It may be familiar; I know people like you and Vinnie [Colaiuta] use it all the time: paradiddles in time keeping.

Yeah, sure.

I've always listened and gone, "mm hmm, mm hmm." Then I suddenly started to find the syncopation to take you to places that paradiddles can in time keeping. So again, something that guys have been using all the time, they're just new to me. I don't make any claim to originating them, but to discover something like that, even if other people have been doing it for years, it's still a discovery to me.

Speaking of paradiddles, have you ever seen Gadd's old black and white instructional video, when they ask him to play an example of what you can do with a paradiddle? Damn!

Yeah, and where that kind of stuff comes from, that's a lesson too.

Your lyrics tell amazing stories. Even with some of the books that I know you've gotten your ideas from, you've really figured out a way in 16 lines or so, to really tell a tale.

That's just time. I just read a quote yesterday, from Graham Green, the writer that applies to all this stuff. He says, "One has no talent. I have no talent. It's simply a question of putting in the time." It's putting in the time. And the drumming stuff too. A lot of that doesn't come easy to me and it took so much practice to get over what I consider my own mental and physical limitations. Some guys, it does come easy to, and lucky them. But for me, I'm always encouraged by the fact that work does produce results like that, and especially unexpectedly. We talked earlier about the unexpected rewards of all my experiences in 3/4 and that was so hard won 'cause at first I couldn't do anything. I almost gave up then. I'm never going to do this. But I kept trying and kept trying. That's the element of my character that triumphs; the will, the work ethic. A little more work and I'll get that. And then when I do, it will be hard won.

That's a great milestone.

Yeah, and it means so much and feels so great and all that stuff, and then people say, "You're so lucky to have talent." "Talent!" Like Graham Green, "I have no talent!"

Have you ever thought about writing a novel, maybe fantasy or science fiction?

Well, anything's possible. I experimented with all that when I started writing prose and just found I want the world that I see and feel.

Do you guys even think about another record before you tour or?

No, this year's booked. People were asking, "Are you thinking about another book?" and I was like, "No." Right now...

You're having fun playing.

Well, my plate is full this year and that's more than enough to think about. By the way. I like the story you did with Matt [Scannell].

Thank you. It was a lot of fun to speak about you through someone else's experience working with you. It's one of the things that I think makes this magazine different: my doing some interviews. Not that I'm doing many. But there are a few guys that I insisted that when it came time to hunt them down for the magazine, I was going to do the hang. And you're the first.

Great. Thank you, I'm honored.

Drums

DW Ls Aztec Red w/snakes And Arrows graphic w/special Black Nickel Hardware

23" X 16" Kick w/3ply rings& fatter batter edge

8" X 7" Rack VLT shell w/6pIy ring and ESE resonant edge

10' X 7" Rack VI] shell w/6ply ring and ESE resonant edge

12" X 8" Rack VLT shell w/6ply ring and ESE resonant edge

13" X9" VLT w/3ply ring

15" X 12" VLT w/3ply ring

15" X 13" Floor

16" X 16" Floor

18" X 18" Floor w/special TB12 drill

14" X 6.5" straight VLT shell

13" X 3.5" straight VLT shell

14" X 6.5" Edge Snare

Cymbals

Sabian

13" Signature Paragon Hats

10" Signature Paragon Splash

20" Signature Paragon Crash

16" Signature Paragon Crash

10" Signature Paragon Splash

16" Signature Paragon Crash

22" Signature Paragon Ride

14" Signature Paragon Hats

8" Signature Paragon Splash

18" Signature Paragon Crash

20" Signature Paragon Chinese

20" Paragon Diamondback Chinese Prototype

19" Signature Paragon Chinese

Hardware

DW 9000 Double Pedal

DW 5500 Hi-hat stand

Sticks

Promark 747 Neil Peart Sig. Model

Heads

Remo

Electronics

Roland inside DW Shells

10" X 6" single headed Rack, & TB12 to shell

12" X 6" single headed Rack, & TB12 to shell

12" X 12" Kick w/tom lugs on both sides, flanged tom hoops, BD spurs & 9907 lifter installed.

Roland Cymbals

Kat MalletKAT