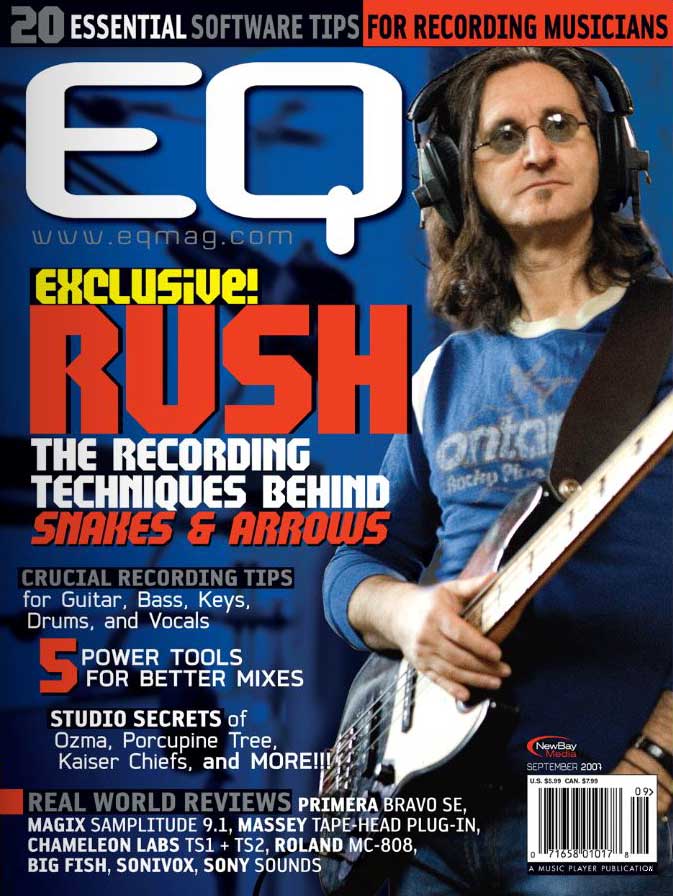

The Recording Techniques Behind Snakes & Arrows

Rush and Producer Nick Raskulinecz Reveal How They Recorded Snakes & Arrows

By Will Romano, EQ, September 2007, transcript provided by Richard Chycki

Sometimes dreams do come true - just ask producer Nick Raskulinecz. Or if your memory is as good as ours, think back to a small interview that ran in the May 2006 EQ, where Raskulinecz - who has worked with Foo Fighters, Velvet Revolver, Marilyn Manson, and others - was asked which band he would most like to produce.

The answer was swift and simple: "Rush. Nobody plays like those guys anymore."

The veteran rock act can still fill gianormous arenas almost 40 years after its inception, and consistently moves hundreds of thousands of records without conforming to popular music standards. And while many bands of Rush's stature are content to find a comfort zone and stay there, the Canadian trio opted to try something different for its 19th studio release, Snakes & Arrows (Atlantic), and give the enthusiastic Raskulinecz a chance to push the band to new, and old, heights.

"Nick said, 'I've been a fan since I was 11 years old,'" relates Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson. "And he told us that when he heard the bass pedals back then, and the way we wrote a chorus or a bridge, it stayed with him forever. He didn't think we should give up on those things - just that we should celebrate our original concepts with a modern package. That really struck a chord with us."

Love Is In Allaire

Initially, the plan was for drummer Neil Peart to cut his drum tracks at Allaire Studios in the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York, and then return to Toronto to finish the album with Lifeson and bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee.

"I got the vibe from Neil that he was very passionate about going to Allaire," explains Raskulinecz. "We were all trying to talk him into going somewhere that was a little more convenient for Alex and Geddy, because they were pretty dead set on staying in Toronto. But I could see something in Neil's eyes, and when he called me up about three weeks before we were to start recording, I asked him point blank, 'Neil, where do you want to do your drums?' He said, 'I really want to go to Allaire.'"

"There really aren't many good drum rooms in Toronto," explains co-executive producer and equipment co-supervisor Lorne Wheaton. "The great Hall at Allaire is the same room we used for Neil's DVD, Anatomy of a Drum Solo. It sounds great, and Neil is used to it. That's the reason we went there."

"I wanted to use my studio for recording guitars," says Lifeson, who had planned on Peart and Lee doing a few at Allaire, and then resuming the project back in Toronto as soon as possible. "In fact, I had everything already set up, because I was looking forward to being in my own space. It's a small, private studio, but it's really good-sounding room."

Less than 40 days later, Snakes & Arrows was done. And the band had not moved an inch since they settled in at Allaire.

"Once we got there, we realized there was a great advantage to being at one studio for the whole recording project," says Lifeson. "The energy in the building was so positive, and the gear is great. They have everything there - amazing guitars, basses, and synthesizers that the owner had been collecting for years and years and years."

Producing Legends

Although Rush has made tremendously successful and classic albums during its existence, the members still looked to Raskulinecz to play the role of a traditional producer. He helped them rewrite and arrange material, and tweak their performances.

"It is real easy to love a band, and then be disappointed in their material when you are working on an album," the producer says. "But I wasn't disappointed at all. I was the just honest. The first time I heard some of the tracks, I told them exactly what could be better about them. I thought we were missing an up-tempo tune with some weird off-time bits, and a big, kick-ass sing-along chorus - which is 'Far Cry'. I felt we were missing an acoustic-based, modern-day 'Closer to the Heart' with a really catchy chorus - which turned out to be 'The Larger Bowl'. And I challenged them to write the most screwed-up, complicated instrumental that they had ever written, and they came back with 'The Main Monkey Business' - which they wound up recording live."

From the earliest days of pre-production, the collective vision of Raskulinecz, recording/mixing engineer Rich Chycki, and of course, the band was to create a record that would nod in the direction of Rush's glorious prog-rock past, pay homage to their influences, and maintain the band's relevance in the current mainstream rock world. As a result, "new vintage" quickly became the buzz term of the Allaire sessions.

"'New vintage' is a good phrase," Lifeson says. "And Rich was so quick at creating and pulling up sounds that define 'vintage' - big, ballsy, powerful, and clear. I was getting all the elements I always wanted to hear in my guitar sound."

Discerning listeners will hear a patented Hemishperes F# chord in the intro of "Far Cry," and recognize the nod to Eric Clapton and B.B. King during the opening guitar break in "The Way the Wind Blows," and Lifeson attributes a fair share of the classic sounds on Snakes & Arrows to renewing relationships with old friends.

"I was using my Gibson ES-335," says Lifeson, name-dropping the guitar he played on such celebrated Rush classics as 2112 and Caress of Steel. "I was hugely influenced by Eric Clapton when I was young, and it was nice to take a little bit of a bluesy approach to a song."

For his part, Lee fussed over a Mellotron - an infamously unpredictable piece of equipment that he hadn't used in years.

"We wanted to use orchestra-like glissandos on 'Faithless,'" explains Lee. "But I had to play the glisses by manipulating the pitch wheel on the Mellotron, which involved finding the right position on the wheel, marking it with tape, them moving the wheel down to another note, and marking that position with tape. I was all very Rube Goldberg."

In addition, Raskulinecz convinced Lee to return to his equally temperamental Moog Taurus - a 13-note analog synthesizer housed in an organ-style pedalboard that had, in the past, allowed Lee to accompany Lifeson on guitar or play keyboard while holding down a bass part with his feet. But because the Taurus tuning is so finicky - Lee remembers having to retune the synth for every new part he'd play in the studio - the band had jettisoned the pedals in favor of samples for recent projects.

"The Taurus pedals are on almost every song - which is something that hasn't happened since 1985's Power Windows", says Raskulinecz. "And that's one of the reasons Snakes & Arrows sounds so big and powerful - you don't hear the pedals so much as you feel them. To record them, we went direct through a Chandler Germanium preamp/DI, and pushed the preamp's Thick button to add more of a low-end rise to the sound. Then, the signal went straight to tape. There was no compression, or any other processing."

Chandler's Cody Brown explains that the Thick button on the Germanium delivers a gentle frequency bump that peaks around 100Hz.

"When you push that button in combination with boosting the unit's Gain and Feedback controls, you can achieve a firmer low end for instruments such as the Taurus," says Brown.

Recording Lifeson's Guitars

Lifeson rekindled his romance with the acoustic guitar for Snakes & Arrows, echoing material from earlier Rush records such as 1975's Caress of Steel and 1977's A Farewell to Kings. For most of the new record, Lifeson played Garrison 6- and 12-string acoustics, as well as his old Gibson jumbo acoustics, and the Gibson 12-string he used on "Closer to the Heart" (from A Farewell to Kings). In addition, he played other acoustic instruments, such as mandola, mandolin, and bouzouki throughout the album. Chris Griffiths of Garrison Guitars had Lifeson's acoustics custom built for the Snakes & Arrows sessions.

"We talked with Alex about what he used in the past, what he has really liked, and what were the deficiencies in the instruments he had used," says Griffiths. "We also asked whether he was looking for volume and projection, or low-end response, and we built guitars around his descriptions. For the 12-string, we used a cedar top to increase midrange response and mellow the overall tone a bit, because a 12-string can tend to sound quite bright. For the GDC 50 - which is his 6-string guitar - Alex was looking for good bass response and good projection, so we went with solid rosewood for the back and sides. That's probably the best wood to use for bass response."

Of course, bringing back the acoustics also brought back the challenge of effectively blending electric-and acoustic-guitar tones.

"We were into having an acoustic guitar running through an entire track to clarify a lot of the chord work, but acoustics can really take up a lot of space," explains Raskulinecz. "To make sure the massive electrics and massive acoustics mixed together, we typically recorded the electric stuff first, and then did the acoustic tracks so we could monitor whether there were any clashes or muddiness. We also tried to rein in some of the frequency spectrum of the electric guitars by plugging Alex into smaller combo amps - a Marshall JTM45 2x12 and a 1964 Vox AC30 - rather than big 4x12 stacks.

"A lot of the reason that you can hear everything is because Alex is playing ten guitar parts, and none of them are doing the same thing," laughs Chycki.

"Take the song 'Far Cry' as an example," adds Raskulinecz. "We did the verse first - which was just a single track - using a Fender Telecaster, an old Musitronics Mu-Tron III envelope filter, and a little 18-watt Marshall combo. Then, for the pre-chorus, we used a goldtop Les Paul and a Budda 45-watt combo. The main riff was the Telecaster and the Budda. For the choruses, we used the Les Paul and a Marshall JMP45 combo, and, on the bridges, we used the Les Paul through one of Alex's Hughes & Kettner amps. The album really was about constructing layers of different guitar tones."

To make tone play easy, all of Alex's amp heads and pedals were set up in the control room, and the speaker cabinets were positioned in the studio's Great Hall - which measures 50' x 35' with a 45-foot cathedral ceiling. Two Little Labs PC Instrument Distro amp splitters simultaneously routed the signals from six different heads to various speaker cabinets, which were all miked with a Shure SM57 and a Newmann U47 FET. Both mic signals were submixed to a mono track, and Rasulinecz assigned each amp to its own channel, which, during the mixdown process, allowed the band to pick and choose which guitar sounds they wanted for each song, or each section of a song.

"We would literally mix and match," says Raskulinecz. "We'd say, 'Let's Listen to the Marshall. 'Okay, let's listen to the Budda,' 'Now, let's listen to the Hughes & Kettner.' Or, we'd audition a combination of things. I'd say, 'I really like the top end of the Budda, and the bottom end of the Marshall. Let's hear those two together.'"

To record acoustics, Chycki typically positioned an Earthworks QTC50 small-diaphragm omnidirectional mic about 12-inches from the body, and pointed at the soundhole. A Royer R-121 ribbon was also placed close to the guitar to exploit proximity effect and capture some bottom end. In cases where an organic-sounding stereo performance was desired, Chycki would use a Telefunken Ela-M 251 tube mic along with the QTC50. The mic preamps were Chandler Germaniums, and a little EQ was often added to preserve the detail of the guitar tone.

"I'd also plug the output of the Garrison's onboard pickup system into a Countryman direct box, and a Neve 1064A preamp," says Chycki. "The direct signal was laid straight to Pro Tools, and we didn't compress it into anything. We just left it there, and we would use the track at mix time if we wanted a real glassy texture - such as on the song, 'The Main Monkey Business.' We really didn't have a super-complex recording path. We were trying to maintain a simplistic, organic approach to recording so that we would not put ourselves into a phase nightmare when it came time to mix."

Although we'll take Chycki at his word, the recording process for the pensive 12-string solo-acoustic piece "Hope" - which conjures the sound of Jimmy Page interpreting Indian music atop the rolling hills of Ireland 'seems far from simple, even if the ultimate effect sounds intimate and organic.

"Well, that was a very mathematical approach to recording acoustic guitar," admits Chycki. "The mic positions were all measured out, and it literally put Alex at the apex of a six-foot equilateral triangle. Alex was rehearsing, and bumping his hands against my tape measure as I was measuring each mic's distance from the guitar. There was a stereo pair of QTC50s about six feet away, and I had a Royer SR-30 about 12 inches from the body. We were recording in Allaire's Great Hall, and the sound was so huge that we had to put down rugs on the floor, and surround Alex with a half-circle of gobos to diminish the reverb time of the space. We didn't want the guitar to sound too echo-y. But it was worth the trouble, because if you war headphones, you can almost feel Alex moving around as he performs."

Peart's Rhythm Method

It's hard not be surprised by the natural timbre of Peart's drums when listening to Snakes & Arrows, as such naked drum sounds have been absent from much of Rush's recorded catalog. Peart used his custom Drum Workshop "West Coast" recording kit - which was built when Peart needed a kit to record some tracks for Vertical Horizon at Los Angeles - Capitol Records studio in 2006, and the drummer was fretting over the logistics of sending his usual setup down from Toronto.

"It's a carbon copy of his stage kit without the electronic pads," says drum tech Lorne Wheaton. "Part of the kit uses Vertical Low Timbre (VLT) shells, which employ vertical, rather than horizontal, wood plies that resonate a little more, and at a lower pitch. We also used his 14" x 6.5" VLT snare for the first time on a recording - which is odd for us, because we'll often show up for sessions with 14 or 15 snare drums. But we didn't take that snare off the kit once."

Another factor that greatly affected Peart's drum sound was Allaire's Great Hall.

"It's a huge space," says Raskulinecz, "but it had a really open and transparent sound, and there weren't a lot of room reflections bleeding into the close mics. This is because we intentionally put a lot of gear in there. We packed the room full of guitar and bass stuff in order to break up reflections. Then, after moving all the gear in, we walked around the room, hit just the snare drum, and listened to how it sounded. When we found the sweet spot, we set up his whole kit right there."

"Of course, we still had to take down the room sound a bit," adds Chycki. "It looked like Neil was recording in Stonehenge, because we had gobos up in a semicircle around the back of his kit."

But even with all the work spent positioning the drums in just the right spot in a good-sounding room, Raskulinecz credits Peart's drum heads as largely contributing to the album's drum sounds.

"They had been on those drums for more than months," says Raskulinecz.

Peart's recording kit also utilized Roland V-Drum pads - positioned over his 15" and 16" floor toms, and off to the drummer's far left - and a Roland TD-20 Percussion Sound Module. Sampled sounds used on the album include Metasmack (a tambourine that makes the scene in "The Main Monkey Business"), a tuned-down roto-tom, a guiro, sleigh bells, and a pitched whistle.

For cymbals, Peart used his Sabian Paragon signature line. "New to this session was something we had been working on with Sabian - a cymbal called Diamondback, which is a type of China cymbal with four tambourine jangles for rivets," reveals Wheaton. "That cymbal is on 60 percent of the songs. It's not real loud, as the jangles won't let the cymbal ring out for any length of time, and it has such a great sound when you use it as a ride cymbal. It's not overpowering, and there's a nice decay."

Because of Peart's extensive set up, proper mic placement was essential to avoiding phase issues.

"Recording his drum set requires tons and tons of microphones, and you really have to have a good understanding of how phase works, as well as the phase relationships of all of these different microphones," says Raskulinecz. "The other thing is that Neil often goes from one side of this huge kit to the other, and we had to make sure we had the whole spectrum covered. I wanted every one of his fills to jump out of the drum set. We spent half a day auditioning mics and getting drum sounds."

For overheads, the team used Earthworks TC30s because Raskulinecz liked their airy top end. For even more high-end detail, a pair of Coles 4040 ribbon mics were positioned up close and in front of the kit - one 4040 to the far right, and the other to the far left. A "crusty old" RCA 44 was placed at the back of the kit, and down low.

"That 44 took such a beautiful picture of the whole kit," says Raskulinecz. "I think that one microphone was responsible for 25 percent of the drum sound when the mix was all said and done."

"The Earthworks overheads were equidistant from the snare, and that contributed to the imaging of the kit, as well," adds Chycki. "Neil was sitting on a road case, watching me tape measure his kit to death to avoid phasing issues. We even made sure the RCA 44 was positioned behind him at the same distance from the snare as the overheads."

"We used a Shure Beta 57 for the top of the snare, and we miked the side of the shell with a Neumann KM84 pointing at the wood, which was Rich's idea," says Raskulinecz. "You can really hear the attack and the punch of the drum by pointing the mic at the body of the snare. The snare bottom was miked with a Sennheiser MD 441. We miked the tops of the toms with AKG C414 TL-IIs to capture detail, and we used Sennheiser MD 421s on the bottoms to pick up the resonance. Neil said this was the first time the bottom head of his toms had ever been miked. I was a little surprised about that."

Peart's bass drum presented its own set of challenges, from phase issues to the physical aspects of miking it.

"Neil prefers to play with both heads of his kick drum on so we couldn't get access to the beater skin," says Chycki. "We ended up taking off his kick-drum heads, putting an AKG D25 inside, and then sealing it up again. That mic obviously has a different phase relationship, because all the other mics are at the rear of the kick drum. The other mics we had were a Neuman U 47 FET, AKG D112, and a Yamaha NS-10 (Editor's note: The Yamaha NS-10 is a studio monitor, but by taking the speaker cone out, and wiring it to an XLR, you can place the driver on a kick-drum head to capture great low-frequency sounds). We aligned the D25 with the other mics using a Little Labs In Between Phase Alignment Device, which checks phase issues, and puts mic signals in phase quickly. This is important, because one of the reasons the drums sound so chunky is that you are hearing them without any phase conflicts. There is no conflict because the image of the kit remains consistent."

Miking issues aside, Peart's recorded performances are breathtaking, and Raskulinecz was up for any tactics that would ensure the drummer's fantastic energy was captured on tape.

"For some of the songs, I actually went out there in the studio with headphones on, and stood in front of him air drumming along to kind of re-energize him," says Raskulinecz.

"Once Nick gained Neil's trust, Neil would do anything he would suggest," says Lifeson, who programs the rough rhythmic arrangements on the band's demos before handing them off to Peart. "There were a number of times when Neil would finish his take, and he'd be totally exhausted, and Nick would say, 'Dude, that was awesome. But you might just want to go out and try one more totally different take.'"

Raskulinecz even demanded more of Peart once the drum tracks were "officially" finished.

"Once the body of the track is done. I'll have the drummer go back and do what I call 'fill passes,'" explains Raskulinecz. "I'll say, 'Now I don't want you to play any of the fills you've already done. I want to hear completely different fills every single time. And I want you to do a fill at the end of every bar.' I do that all the time with Taylor Hawkins and Dave Grohl of the Foo Fighters. A lot of times, the fills that come out of the fill passes are the ones that make it to the final drum take."

But while some fills might have been edited into the final drum passes, Raskulinecz is quick to assert that no fiddling with Peart's actual performances occurred.

"We recorded on Pro Tools, but this is literally a performance record," he says. "I'm not going to sit there and grid edit Neil Peart's drum performance. That's like, against the law."

Tracking Lee's Bass

"Geddy prefers to record his bass using three individual signal paths," says Chycki. "They just all happen to be direct - which also means there are none of the phase issues you get when running direct and miking a bass amp simultaneously."

The signal chain included a Tech 21 SansAmp DI, a Palmer Speaker Simulator, and a Martech MSS-01 Bass DI. Chycki recorded each direct line through a Neve 1081 preamp, and also employed Universal Audio LA-2 compressors.

"Everything started with Geddy's '72 Fender Jazz Bass," says Raskulinecz, "and all of his sound is in his fingers. It's just a matter of getting what he does directly into the recording format."

"I'm really happy with all of my little direct boxes," says Lee, who, in addition to the Jazz bass, used a fretless Fender Jaco Pastorius Tribute Bass on "MalNar," and a Fender Custom Shop Fender Jazz Bass on "Bravest Face." - "I found a very friendly and portable way to take my bass sound wherever I go without the cumbersome use of giant, booming amplifier cabinets."

Capturing Vocals

"I stumbled onto my favorite vocal sound, which is a Soundelux 251 into a Martech MS-10 mic preamp into a crusty, old dbx 160XT compressor that came off a live sound rig," says Raskulinecz.

"Every producer I work with has a new mic that sounds better than any mic ever made," says Lee with a laugh. "But I was happy to try whatever Nick wanted - as long as the vocals sounded good. Normally, I like to work right up on the mic, but the Soundelux is particularly sensitive, so I had to back off a little bit."

Mixing, Mastering, and Digging the Results

"We mixed over the course of nearly four weeks," says Raskulinecz. "And while all of the band members have really sharp ears, they gave me a lot of freedom."

"It's not a super-loud record," says Chycki, who mixed the album on a Neve 88R at Ocean Way Studios, "and it was not hyper-compressed. We really wanted to make a record that's clean, wide big, and open. We paid careful attention not to beat the crap out of bus compressors, and we did take nuclear weapons to make sure they didn't crush it to death at the mastering facility."

"I'm really sensitive to compression," adds Raskulinecz. "When things are too compressed, you lose dynamics. This is why we didn't track with a lot of stuff compressed. We saved the compression for the mix, where we would have the most control over the dynamics."

The mastering process was run off a one-inch analog mixdown master tape, and then the mastered version of the album was also tracked to analog - a strategy that Raskulinecz feels gave Snakes & Arrows its "sonic boldness."

"Nick is a very enthusiastic, positive, and creative guy," enthuses Lee, as he assesses the finished album. "I don't think anyone realized what a great chemistry we had on our hands,"

"This is definitely a Rush record," adds Lifeson, "and the sounds are very vintage and classic - especially the guitar tones. "When you have a cheerleader like Nick, it just opens so many doors. I'm an early riser, and the whole time we were recording, I'd be looking for jobs to do in anticipation of getting started. Every day was like that. We couldn't wait to get in there and start playing."

"I genuinely love the music and the songs," says Raskulinecz. "This wasn't about producing a big-name band, or a getting a credit. It was just about making a really great record. I wanted to do it for these guys. They deserve it. I want them to be on top."

Quotes:

"I challenged them to write the most screwed-up, complicated instrumental that they had ever written." - Nick Raskulinecz

"The Taurus Pedals are on almost every song - which is something that hasn't happened since 1985's Power Windows." - Nick Raskulinecz

"We really didn't have a super-complex recording path. We were trying to maintain a simplistic, organic approach to recording so that we would not put ourselves into a phase nightmare when it came time to mix." - Rich Chycki

"I'm not going to sit there and grid edit Neil Peart's rum performance. That's against the law." - Nick Raskulinecz

"Every producer I work with has a new mic that sounds better than any mic ever made." - Geddy Lee

"We paid careful attention not to beat the crap out of bus compressors, and we did take nuclear weapons to make sure they didn't crush it to death at the mastering facility." - Rich Chycki

Getting Vintage Guitar Tones Without Vintage Gear

Okay, so you don't have a guitar collection like Alex Lifeson, who can pull out a vintage guitar (and vintage amp) to get a vintage sound. How can you get that elusive, coveted sound?

First of all, use a vintage style of playing. Listen to guitar greats such as B.B. King, Eric Clapton, Buddy Guy, and Mike Bloomfield - most didn't use vibrato tailpieces, choosing to get their vibrato from their fingers. Also, notes were often not bent up 100 percent to pitch, but just a shade flat to add tensions. Phrasings were generally more economical than later guitar players, with good usage of space, as well as flurries of notes.

As to tone, remember that a small tube amp can sound just like a big tube amp as far as a mic is concerned. Avoid dialing in too much distortion. Find that sweet spot where the amp starts to break up, and go just a bit further. Runaway distortion "scooped" midrange frequencies didn't come into vogue until later. And if you're using a software amp simulator, you may need to bite the bullet and upgrade. Newer amp sims, like IK Multimedia's AmpliTube 2, take advantage of more powerful technology, and more experienced modeling engineers to give a smoother transition from clean to distorted tones. Again, it's all about finding that sweet spot where an amp isn't too clean, or too dirty, but just right.

Vintage EQs, whether built as part of an amp or in a rack of gear, tended to be built around largely passive circuits, with amplification used to make up for signal loss. This translates to gentle slopes and natural-sounding EQ curves. If you're EQing with a parametric, use a broad bandwidth, coupled with small amounts of boost. Also, try some of the plug-ins that emulate vintage EQs, such as those that aim for the sound of a Pultec EQ.

Finally, remember to explore the tonal options of your guitar and amp first, before you even think about setting up a mic, let alone processing or mixing. The best vintage sounds happen between your fingers and the amp's speaker. Ideally, all your mic should need to do is pick it up. - Craig Anderson, Emulating Taurus Pedals

The Taurus bass pedals had all the benefits of analog synthesis - when they worked. Because they were based on analog electronics, there were always the issues of component drift, turning instability, and reliability.

If you're looking for that sound, though, you're in luck. Due to the iconic status of the Minimoog, several software companies (in particular Creamware, Arturia, and GForce) have created plug-in virtual instruments that emulate its sonic character with surprising accuracy. As this sound is very close to that of the Taurus, with suitable programming - long sustains on the envelopes, and keeping the filter enveloping from kicking up too high in frequency - you can get those growling, huge bass sounds formerly available only with analog synthesizers. - Craig Anderson