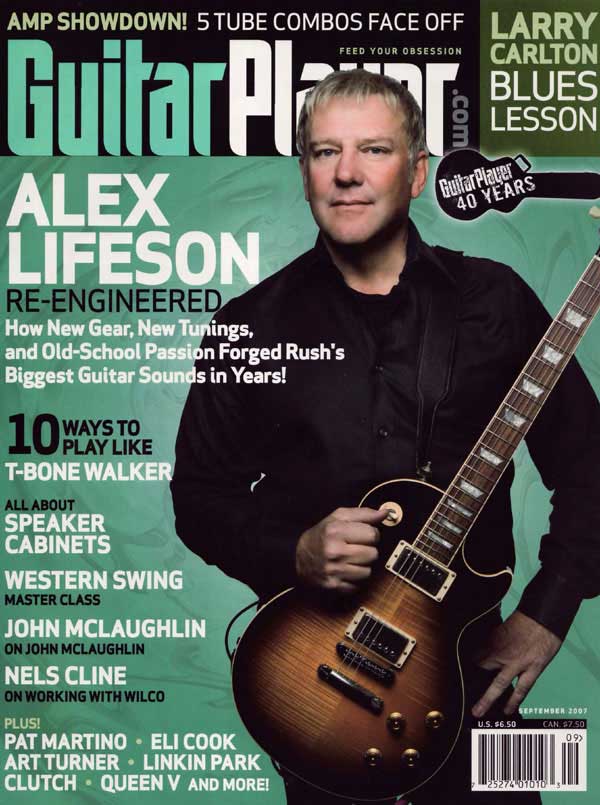

Alex Lifeson: Different Strings

By Matt Blackett, Guitar Player, September 2007, transcribed by John Patuto

Alex Lifeson gets out of his comfort zone to craft his biggest tones ever

It's impossible to talk about Alex Lifeson without talking about about his band of the last three-plus decades-Rush. He makes up one third of this three-headed beast that has defied all musical, business, and cultural logic since its self-titled debut in 1974. It's not fair to say that Lifeson has been overshadowed by his bandmates, bassist Geddy Lee and percussion professor Neil Peart.

All three of them have ruled players' polls for many years, and each is an icon in his own right. But even in the most egalitarian band on the planet, some members are more equal than others, and, whether he knows it or not, Lifeson is the glue that holds Rush together. Alongside Lee's frenetic bass lines and Peart's hyperkinetic drum accents there is Lifeson-equal parts rock dude, sonic adventurer, and texturalist. His huge washes of chorused power chords and clever arpeggios have been the mortar between Lee and Peart's bricks since the three first threw down together. And what they have built together is pretty damn impressive, with just about every record going platinum, every show sold out, and every fan totally diehard.

Each step of the way, Lifeson and his pals have been musicians' musicians. After all, this is the band that famously tracked its 11-minute opus "Xanadu" in one take. First take, entire band. That's kind of the musical equivalent of pitching a perfect game-with 27 three-pitch strikeouts in a row. As unfathomable as that may seem, the first few minutes of a Rush rehearsal prove how they did it-as well as give the distinct impression they can do it again whenever they want to. The three of them hit their instruments with a confidence and authority that few bands can touch.

They are one of the tightest rock bands of all time, but not in a quantized, Pro Tools kind of way. Theirs is a much more elusive tightness-one that comes from an almost imperceptible, indefinable looseness. Listening to them rehearse, it's impossible to know if Lifeson is ahead of Peart's beat and Lee is behind it, or vice versa. The only thing you can be sure of is, whatever the heaviest way to hit a downbeat might be, these guys hit it that way every time. They are crushingly heavy-even when playing happy-sounding major key tunes. And Lifeson effortlessly cranks out unbelievably expansive soundscapes with three-dimensional richness, crystalline highs, and subterranean lows. This is the way he plays every day. It's who he is.

Lifeson is an impressive guy on every level. He walks into a room, and he takes it over, but in the mellowest of ways. He looks far younger than his 53 years, with a disarming smile and an innocence that belies his long career-a career that has taken him from high school gymnasiums to huge arenas and all points in between. He is humble and unassuming about his talents, as well as thoughtful and considerate- not like a Hallmark card, but in the sense that he thinks about every question before answering. If he ever gives what appears to be a stock answer, it's only because he has, over the years, found a turn of phrase that he likes-the same way anyone might repeat a favorite lick or a good joke.

At Rush's rehearsal space on the Toronto waterfront, Lifeson took time to expound on what makes this band tick. He also talked about Snakes & Arrows [Atlantic], the first Rush studio album in five years, and the album's producer, Rush fan Nick Raskulenicz [Foo Fighters, The Mars Volta, Fu Manchu]. He bore the scar of a bizarre golfing accident that had left a bruise under his eye-although it couldn't diminish his deep love for the game of golf anymore than the scars the music business has left on him could lessen his passion for playing guitar.

Your producer, Nick Raskulenicz, was hardly even born when your first record came out. How did his relative youth influence the sessions?

He says the first concert he ever saw was us. His mom took him. He's a Rush fan, but he's really a huge fan of music in general, and he's a player-he plays drums, guitar, and bass. The interesting thing with him is he realizes the whole history of this band-where we've been and what we've done. We're always looking for something to move us forward, and, a lot of times, we tend to run from our past in the search for a new place. He pointed out how important it is for us to remember where we came from, and to integrate all of that as we move forward. He told us not to discount things from our past. Nick also encouraged me to approach the guitar sound of the record so that everything would have a pretty big body to it. Geddy was a big proponent of doing the record straight ahead, with very few overdubs. But once we got into it, and started to develop it, the size and the character of the tunes started to grow, and it made it hard to do it that way. There are a lot of big guitar layers, and Nick was really instrumental in achieving that, as was [engineer] Rich Chycki. The two of them worked so well together.

What did you hear in his body of work that made you feel that he could be a good fit for you guys?

I hear a lot of these producer CDs, and it's a little surprising how much crap is on some of them. On Nick's, everything was really well crafted. The songs were solid, the sounds were solid, and the mixes were solid. To us, it sounded like a guy who gets really involved with the arrangements, the songwriting, and how the songs come to life.

I would guess some producers might be intimidated by all that you've done, and therefore be hesitant to tell you to change something.

I suppose-but that's certainly not the type of producer we want. We want someone who is engaged, and who is not afraid to say what they think. When we bring someone in, we expect them to suggest alternatives. If it works, great. If it doesn't, that's great, too.

What kind of suggestions did Nick make?

There were a bunch of songs he didn't do anything with. There were a number where he might make minor changes to the arrangements- a slightly longer chorus, or a shorter bridge. That sort of thing. He made major changes to a couple of songs, such as switching the prechorus with the chorus on "Spindrift." He thought that a few of the parts on "The Main Monkey Business" were superfluous, so we cut those out. But what he was really great at was squeezing the last ounce of performance from all of us. We'd get a take, and it would be great, and Nick would say, "That was awesome! Do you mind going back in and trying it one more time?" I gotta say, we fed off that. Every single day, when I got up in the morning, I couldn't wait to get into work. It was such a fun and exciting experience.

You originally planned on doing your guitar parts at home. How did you end up recording at Allaire-the New York studio where Snakes & Arrows was recorded?

The intention at Allaire was to get drum tracks. That's it. Geddy and I talked about this on our way there. He said, "I don't care how many bass tracks I get down. As soon as the drum tracks are done, we're coming home. We're going to work in Toronto, and try to have a semblance of a normal life while we're working." In fact, I had spent some time at my studio getting ready. I had amp heads stacked on the desk in the control room. I had the speaker cabinets set up, and all the mics laid out. I was really looking forward to doing guitars at my studio because I know the room, and I'm comfortable there. But when we got to Allaire and Neil had gotten his first track done, we hung out in the control room until 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning. We just got into the vibe, and we soaked up the room and the sound. The energy is so positive there. It was really a great place to be. All of our plans flew out the window at that point. Then, of course, there was a panic. I thought I was just doing bed tracks, and I wouldn't need all my gear. So I had a couple of amps, and maybe half a dozen guitars. But rather than ship all of my stuff to Allaire, I decided to go with what we had. Nick had brought some great old amps-a 50-watt Marshall, a 100-watt Marshall, a 20-watt Marshall combo, a 50-watt Marshall combo, and a great Vox AC30. They had a lot of stuff at Allaire, as well, like this Bogner cab that sounded really, really awesome, and I had some of my Hughes & Kettner gear with me. So we stacked a bunch of heads in the control room, and we set up this huge line of amps out in the room.

Do you enjoy getting out of your comfort zone like that?

I totally love it. It keeps everything fresh and exciting. Having that variety is really important. Sonically, it seems to me that with a lot of records you go through these periods where there's the guitar sound and the drum sound. I guess that's true with all eras, but it's certainly happening now with guitar. A lot of the guitar tones seem to be quite similar. They're quite saturated. It's great to go back to old vintage gear, because my style of playing is not cranked to a million and super distorted. I always tend to pull back on the guitar, and pull back on the amp a bit so it's more in the hands-the hands express what the part is. I like making the part heavy by the way I play, and not by the equipment I'm using.

Let's talk about some of those parts. How did you get the tones in "Far Cry"?

There are a lot of guitars on that song. I think part of it was my Gibson ES-335-the one from back in the day. I used my 335 for a lot of this record-along with my Les Pauls and my Tele. Those were the primary instruments. The wah-type sound in the intro is Nick's Mu-Tron pedal. I'm also running my pick up and down the string as I play. The solo was my ES-335 into the Hughes & Kettner Switchblade and Bogner cab. To get the sustain in the solo, we just cranked up the monitors. I hit the notes, held my guitar up to the control room monitors, and shook the crap out of it. It was screaming loud.

You don't stand out in the room with your cabinets, then?

I don't. Well, for a specific need, I will. But I'll tell you-communication is so much easier in the control room. Dialing in the sound with the heads there is so much easier. I think you pay a little bit for it in terms of cord length and things like that, but, ultimately, it's a better way to work for me.

How many guitar tracks are in the verse of "Armor and Sword"?

For the verse and chorus, it's one track of acoustic and two tracks of electric, plus a third electric playing the harmonics. Most of the clean tones were through the JC-120 or the AC30. The crunchier tones were the AC30 cranked up, or the smaller Marshall combo. The heavier distorted tones were the Switchblade through the Bogner cabinet, or a Hughes & Kettner cab loaded with Celestion Greenbacks.

There's some really cool interplay between you and Geddy on "Armor and Sword." It almost sounds as if he's extending your chord voicings so you don't have to.

Yeah-and he's playing chords on his bass, as well. I've always tried to play fairly broad, big chords, because in a three-piece band, I think you need that. When he plays chords, it takes a little pressure off me, and then I can play single-note lines, and we don't feel like there's a hole in the sound. We don't feel the need to use keyboards like we did at one time to take up all that space.

Are you playing mandolin on "Workin' Them Angels"?

Yes-mandolin and bouzouki. That's a funny story. I went to visit a friend in Greece last summer who had a bouzouki. When I was there, I bought one, and I would get up every morning around 6:00 am, and sit on the edge of this cliff with my feet literally dangling over. I would sit there with my coffee, strumming this bouzouki, and learning how to play it. These little fishing boats would go by, and the fishermen would be shouting and waving at me. It was awesome. So I had to get it on this record somewhere. I had this For "The Larger Bowl," I played a Garrison G-50 CE and a G-50 12-string. I think I used a Gibson J-150 on the second half of the verse for a slightly different tonality. In the studio, the acoustic tracks were primarily constructed with the J-150, the Garrison 6- and 12-strings, a Larrivée small body, and a Gibson J-55 in Nashville tuning.

"The Larger Bowl" is totally driven by your acoustic guitar. Did you write it on acoustic?

Yes. Everything was written on acoustic. For "The Larger Bowl," I played a Garrison G-50 CE and a G-50 12-string. I think I used a Gibson J-150 on the second half of the verse for a slightly different tonality. In the studio, the acoustic tracks were primarily constructed with the J-150, the Garrison 6- and 12-strings, a Larrivée small body, and a Gibson J-55 in Nashville tuning.

How do you like the Garrisons?

I really like them a lot. There's something about the sound that is very controlled and very tight. It's not a deep sound-like you would get from a jumbo-and it's not as warm as a dreadnought. They have a brightness in the top end, and a tight bottom end. The concert-style body just works nicely for me, and they're also very easy to play.

You've always been a big fan of the acoustic, but you seem more into it than ever.

I was playing a lot of acoustic guitar before we started the record. I went to see Tommy Emmanuel when he played here, and that was really inspiring. The way he caresses the notes is fantastic to watch. I went to see Stephen Bennett, and, afterward, we got together and played some. I tried to play his harp guitar-which was impossible to play. He gave me a half capo, and told me to have some fun with it. He said, "See what you can do when you have open strings on the top or the bottom." That was really inspiring, too. I ended up using that partial capo on "Bravest Face." I think the capo was on the fourth fret, and I played at the seventh fret with the top strings open. That was a funny thing. We were working on that song, and Geddy left the room. I was just sitting around, so I capoed a guitar, and started strumming. Nick said, "We've got to record that!" So he recorded me, and just inserted it into the song. It was one of those chancy things. Hence, I gave Stephen a credit on the record, because he moved me to think in different terms. I also had a meeting with David Gilmour when he was here. It was the first time I'd seen him play. I went back to say hello, and he was a very engaging, charming guy. We talked a lot about the power of the acoustic in terms of writing, because it doesn't lie. It tells you straight up whether an idea has merit.

Your Jimmy Page influence comes out in "Hope." What do you like about the tuning on that song?

That song is in D, A, D, A, A, D. What I like about it is that the two As are next to each other, and one is always ringing out against the other. This tuning really makes it sound like there are multiple instruments playing because of all the sympathetic notes. I'm always trying different tunings. Some of them are terrible, but I love how they make you start all over again. All the things you know don't mean a thing, and that's very exciting to me.

Your solo on "The Larger Bowl" has a cleaner tone than you normally get.

I think that was my Tele and the Marshall 50- or 100-watt run very clean. I really wanted a solo like that-bright and clear. I think it's a little more uplifting and positive. To solo with that kind of tone, you really have to feel confident. You have to be able to express yourself with the limitations of not having the kind of sustain you're used to.

Your solo tone on "Bravest Face" is the cleanest you've ever put on a record.

That tone is super clean. It's my 335 and the AC30. That solo was so much fun, because I never get to solo with a tone like that. It required a whole different thought process, and I loved it. I wanted to keep going and going, but Nick said, "We've got it!"

Have you ever used AC30s on Rush records?

I did on Feedback, but not before that.

You sound exactly like yourself whether you're plugged into a Vox, a Marshall, a Gallien-Krueger, a Hiwatt, or a Hughes & Kettner. Do you still feel like yourself when you plug into a different rig?

That's a great question, but, yeah, I do. I totally do. I don't know what my sound is, or what my style is, or what makes it different, but it always sounds familiar to me no matter what amp I'm playing through. I have things I always gravitate to-like I always take the volume down to 7 or 8. That's the first thing I do. I guess I've always felt that you've got to be able to go up somewhere. For a chunky sound, that's how I do it.

When will you open it all the way up?

For solos-or when I need something really heavy where I want to crush the bottom end.

What about the backwards textures in "Spindrift." They add an unsettling vibe to a song that's already pretty creepy.

We talked about the idea of having little 30-second bits at the beginning of songs. We didn't really develop that, but "Spindrift" was one example-as was "The Way the Wind Blows." I thought it would be kind of cool to have some backwards stuff at the beginning. The song is so heavy that I thought something atmospheric in the intro might work. From there, it was a matter of messing around with the melody line, learning it backwards, and coming up with this thing that Neil called "psychedelic surf music." We wanted to create tension and creepiness until it gets to the chorus, which is very pumping and uplifting.

What are the other guitar layers?

There's an acoustic playing the staccato part, and I used Les Pauls and a 335 for the octaves to the melody.

Who came up with the main riff?

Ged and I came up with it while we were jamming. We never think in terms of who wrote what. We start playing, and these things just come out. It's hard to describe how it works. "Far Cry," for example, was written in minutes, and the lyrics were done the next morning. We labor over some tunes for quite a while before they take shape, but some-like "Far Cry"-are done really quickly. That's always a relief.

You get super bluesy on "The Way the Wind Blows." You used a lot of blues scales early in your career on tunes such as "The Temples of Syrinx," but it didn't sound like the blues. This does. What's the difference?

I've always loved playing that way, but there was never really an outlet for it in our music. I'm a second-generation blues guy. I learned from Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page. I think it's deep inside me. Most of the stuff I played in the early days was based on blues scales. But kind of like Jimmy Page used to do, if you play those scales in a certain way, they take on a whole different character. This was an opportunity to be a little-I don't know if "purer" is the right word-but I wanted to be more rooted in that genre. It seemed to work really well for that song, and it's certainly a lot of fun to play. That was my 335 into the Switchblade.

Rory Gallagher opened for Rush back in the '80s. Did you get any blues inspiration from him?

Absolutely. He was awesome. We opened for him in 1974, so it was great to do those shows with him in the '80s. I learned a lot from him. All those pick-harmonic things I do-I got those from him. I also loved his use of syncopated delays. I think he was an essential player for that period, and he was just a terrific person. He influenced a lot of guys. He was a huge influence on the Edge.

When you composed solos that were more modally based, like "Limelight," was that a conscious move away from blues scales?

I suppose so. You're always looking for something else-somewhere else to go, another area of sound to fill in.

You've gotten a lot of love for your "Limelight" solo. What are some solos that people don't mention as much that you feel contain your best playing?

"Emotion Detector" from Power Windows. That's one of my favorite solos. It has that combination of soulfulness and articulation that's very tense, but fluid at the same time. I have to say, though, that I think the "Limelight" solo is still my favorite. It's a unique sound-very elastic and plaintive. It's sad.

A defining characteristic of your soloing-especially on tunes like "The Trees" and "YYZ"-is your use of really wide interval skips, often involving open strings. Where do you think that comes from?

I got a lot of that from Allan Holdsworth. Around that time in the late '70s, I was quite influenced by his left-hand work-the way he pulled and played without picking.

You've said many times that you don't think Rush could get signed in today's musical climate. What advice do you have for guitarists coming up today-knowing full well that they can't do it the way you did?

I think at the end of the day, it all comes down to persevering and learning your craft. If you're good, your chances of doing something are greater than if you're mediocre-although there's so much emphasis put on mediocrity these days. I think you have to stick with it, and figure out what satisfies you as a player, as a musician, and as a songwriter. It's certainly a lot more difficult out there. When we were coming up, the record company signed you for five records. They hoped the first three were the ones where you molded yourself, and the next two were the "payback" records. That situation doesn't exist anymore. Nobody takes chances anymore. I hold out hope that we're simply in a transitional period, and we just need to find a new direction, and a new way of doing things.

Analog Kid Meets Digital Man

Snakes & Arrows producer Nick Raskulenicz was just 12 years old when he saw Rush's Moving Pictures tour. Here, Raskulenicz talks about what it was like to work with Lifeson, and how the two of them created the album's huge guitar tones:

"What I wanted to do with this record was to make the sonic follow up to Moving Pictures," says Raskulenicz. "I always felt something happened between Moving Pictures and Signals. Moving Pictures was dark and heavy and ethereal with a ton of guitar. But when Signals came out, it was like there was no more guitar.

"When Alex decided to do his guitar tracks with Geddy and Neil at Allaire Studios in New York, rather than at his house, I was stoked. It would have sounded great at his house, but the vibe and the camaraderie of them all in the same place was really important to make the record the right way.

"I had a pretty clear idea of what I felt the record needed from a guitar tone standpoint. I went to Alex's house on one of my first meetings with him, and I asked him where his old Hiwatts and Marshalls were. Well, he doesn't have any of that stuff anymore. I thought there was some big Rush warehouse with all that stuff, but there's not. I have a lot of that kind of gear, so I brought a really great old Hiwatt, a great old Orange, a kick-ass Marshall, and a few newer amps. He sent for his Roland JC-120-I wanted him to bring that. I set up five or six different cabs-all with different speakers-and then I set up all the heads in the control room: the Orange, Marshall, Rivera, Budda, Hiwatt, and a couple of his Hughes & Kettners. We put a couple of combos in the tracking room, as well. There must have been ten amps set up. I used Little Labs PCP Instrument Distro amp splitters, and I chained two of those together so one guitar could feed six amps at once. Each amp was on its own mixer fader, so Alex and I could call up different combinations of any of them for whatever the song needed. I would mic all the cabs with a Shure SM7 and a Neumann U47 FET. I miked the bottom speakers, routed the Signals into Neve mic preamps, and then I summed them to one track. We used tube mics on some of the combo amps-like the 18-watt handwired Marshall and the JTM45 2x12-to get more detail. Those amps weren't cranked super loud, and they have a huge sound at that low volume.

"A lot of Alex's tones were blended with dirty and clean amps. On the prechorus to 'Armor and Sword,' we used the Orange head and a Marshall 2550. The Marshall was totally saturated, and the Orange was totally clean to provide the body and low end that the Marshall didn't give. On the main riff, there's a track where all Alex does is play one note on the Gstring through the JC-120 with the chorus on. That's an awesome sound. The 'Far Cry' intro was his Tele through the little 18- watt Marshall, and he did two tracks of his goldtop Les Paul through a Budda 45-watt combo for the main riff. He used a Rivera Knucklehead Tre on 'Spindrift.' We needed a huge bottom end, and that's just a fantastic head. I also brought my 1964 Vox AC30, and a lot of the semi-clean tones on the record were that amp.

"Alex has a lot of great guitars, but I really wanted him to bring his old Gibson ES-335 that he used on Caress of Steel and 2112. That guitar is on 50 percent of this record, and it's part of the reason this record has that familiar sound to it, because that's the guitar we all love. "Another key element to the guitar tones were these Mogami Platinum cables. I've listened to every guitar cable there is trying to find the quietest ones with the least tone coloration, and these are the absolute best guitar cables I have ever used.

"One thing the band did for this record was writing everything on acoustic. If you listen to the demos, there's no electric guitar-it's all layers of acoustics. There's a bed acoustic track on almost every song that goes along with the heavy stuff. Alex uses these Garrisons that sound fantastic, and I also got him to bring out some of his old Gibson jumbos and the Gibson 12-string he used on 'Closer to the Heart.' Mixing was challenging, because we had all these big electrics and these giant acoustics. On some parts, there could be 15 guitar tracks! We had to clear some space to hear them all, so we filtered the acoustics pretty heavily. If you soloed one of the acoustics, it might sound like it's coming out of an AM radio because we had taken all of the bottom out of it.

"I've been lucky enough to work with some great bands, and I've made some great records, but I don't know if I'll ever have an experience like this ever again. I even tried to get them to cancel their tour, because I wanted to keep working! If I get to do another album with them, I want to make a double album!"

Lifeson On His Live Rig

"I use two Alex Lifeson Model Hughes & Kettner TriAmps as my main stereo sound," says Lifeson. "In two of my monitors, there's a 15ms delay between the two TriAmps so I can get a left and right sound, leaving the middle monitor open for vocals, drums, and bass. I use two Hughes & Kettner Switchblades for peripheral sounds. They'll have various effects on them, and they'll be panned hard left and right, and I kick in those two amps to create the presence of another instrument."

"My rack is pretty straightforward. I don't have a lot of stuff in there, but it's really effective. The main things are a Dunlop DCR-1SR Crybaby Rack Wah, a T.C. Electronic 1210 Spatial Expander + Stereo Chorus/Flanger, and the T.C. Gforces- I use three, and one is a spare. I use the 1210 for chorus. I may add a second one or use a Loft chorus. The Loft is the chorus on the 'Limelight' solo. I have a couple of Behringer mixers that I run into the Voodoo Lab GCX switchers."

"This is part of the stable of guitars for this tour. I've got a couple of Gibson Les Pauls with piezos in them. I also have a Gibson Howard Roberts that has a piezo and is tuned G, G, D, G, C, E [low to high] for "The Way the Wind Blows." My white ES-355 is back out again this time around. That's my baby. It's just so deliciously great sounding. I have an SG with a whammy-it's in standard tuning. I have my Gibson doubleneck here at rehearsals, but we're still working on the set list, so I'm not sure if it will make an appearance. I'm bringing Garrison 12- strings in D, A, D, A, A, D tuning for 'Hope' and 'The Main Monkey Business.' I'm also bringing a Garrison G-50 that I did most of the recording on the album with. I run my acoustics through Fishman Auras. Those really help the piezo tone-they're very acoustic sounding."

At Lifeson's feet are an Ernie Ball volume pedal, a Dunlop DCR-1FC foot controller, an Axess Electronics FX1 MIDI Controller, a set of Korg MPK 180 bass pedals for triggering keyboard sounds, and a lone Boss TU-12H tuner.

Working Men

When asked to reflect on some of the great guitarists Rush has toured with over the years, Lifeson said: "It was always great to be in the presence of other players, to watch them play and get to know them. It's not like we were ever competing. We were brothers. That's the way I've always looked at it, and I much prefer to look at it that way. I learn from all of them, and I'm grateful for the opportunity to play with some amazing players. I see it as a gift."

Now some of those guitarists get the chance to repay that gift, and talk about what it was like to be on the road with Rush:

Steve Morse: "The Steve Morse Band was on the Power Windows tour, and it is a highlight of my career. I remember Alex as being one of the most relaxed and cordial rock stars I'd ever met. I loved the way he used big chord voicings with open strings included to make a broad backdrop for the tunes. Some of his voicings have become classics of the electric guitar-like his chords in 'Limelight.' Everything about that tour was great. Rush is one of the most original, honestly hard-working, solid-as-a-rock bands. Bands like Rush and Dream Theater are the role models that show bands can exist by constantly pleasing their devoted fan base with great music. Thanks, Alex, Geddy, and Neil!"

Paul Gilbert: "My first big arena rock tour was when Mr. Big supported Rush on their Presto tour. One of the best memories of my life is running up and down the stairs of the arena every day while Rush was doing their soundcheck. I felt truly lucky. Some people jog to a Walkman. I could jog to Rush live every day! I love Alex's guitar playing so much. I spent countless hours playing along with Hemispheres, Moving Pictures, and 2112when I was a teenager. I love his shimmering chords, his giant single-note riffs, and his memorable and air-guitar-inspiring solos. Plus, he had an awesome perm, giant bell bottoms, and a kimono. Damn! My favorite rock instrumental songs are by Rush. When I began to write my own instrumental record, I used late-'70s Rush music as my sonic template. The song 'Hurry Up' was the result. Actually, 'Hurry Up' means Rush!"

Larry LaLonde: "Primus toured with Rush on their Roll the Bones tour. They're the one band that we're all fans of, and Alex is way up there on my personal list of important guitar players. It's him and Eddie Van Halen probably. I was always really into the Moving Pictures album and I love "The Trees" with that classical intro. That's what's great about Alex - he's so well rounded. He plays innovative chords, incredible melodies, and solos that just stick in your head. He combines all that with a great tone and an amazing use of effects - I mean there's no way you can improve that."

Vinnie Moore: "Opening for Rush was definitely a highlight for me. I watched their show almost every night. I really liked Alex's playing, and I especially dug his rhythm parts. He has some very catchy riffs and cool, half-distorted sounds. I like the chord voicings he uses and the way he orchestrates his parts-I think that's his signature. I will tell you one thing, though-Alex can't play very well when you put pictures from girly magazines on his pedalboard and monitors. I tried this on the last show of the tour, and he made more mistakes in five minutes than he has probably ever made. He had to get his tech to take them away so he could get through the second song!"

Eric Johnson: "My band toured with Rush in the early '90s. Alex got a very ferocious tone-his style really filled up their three-piece sound extremely well. Rush is one of the main innovators of their style of music, and they've consistently stood the test of time. Alex has a lot of passion in his playing, and that's one of the things that makes Rush's appeal so strong."