Guitar Legends

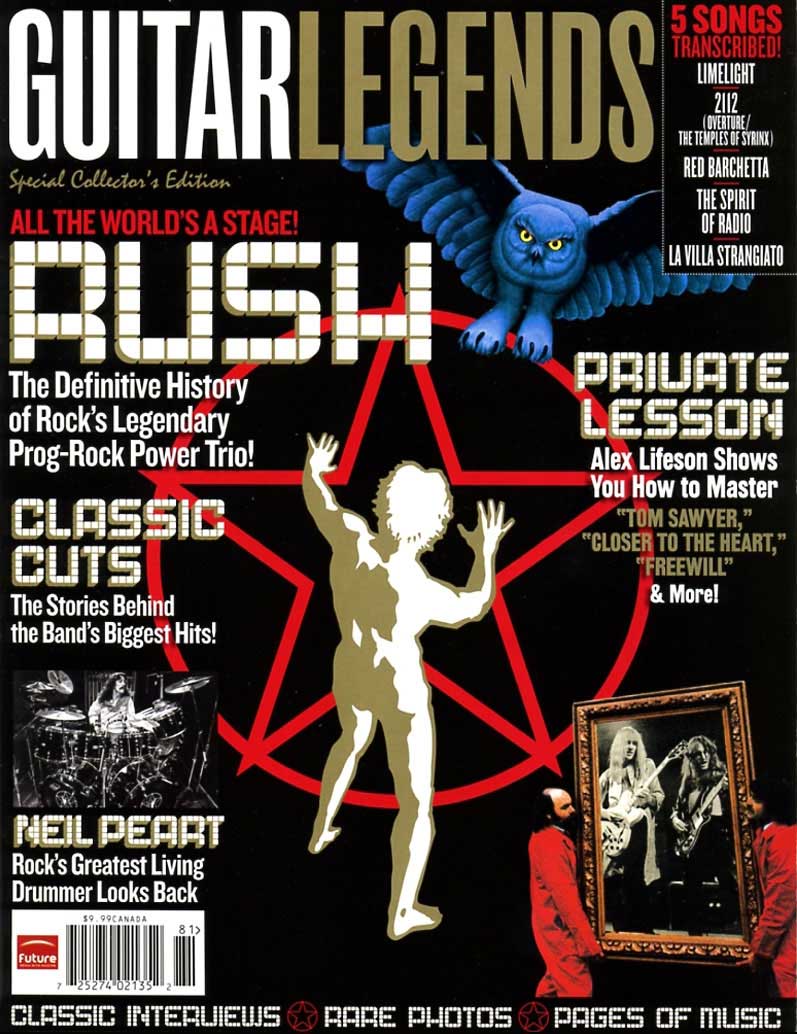

Rush Special Collector's Edition, December 2007, transcribed by pwrwindows and John Patuto

This special collector's magazine includes a mix of new and previously published articles from Guitar World, Bass Guitar and Classic Rock magazines.

Rush: Chronicles

By J. D. Considine

Through more than 33 years rush has remained the ultimate prog-rock powerhouse. guitar world presents the history of the group that blended high-pitched vocals, extended instrumentals, sci-fi imagery and keyboards and somehow made it all work.

In 1974, when Rush released a self-titled album on their own tiny label, nobody imagined that this little-known Toronto power trio would last another three decades, much less that it would become one of the most influential names in hard rock. Thirty-four years later, however, Rush are an institution, with 25 albums (not counting compilations) under their belt and more than 40 million in worldwide sales.

But those numbers tell only part of the story, for the importance of Rush cannot be measured in sales alone. As the trio moved from the bluesy basics of "Working Man" to the progressive metal of "2112," "A Farewell to Kings" and "La Villa Strangiato," it raised the bar for mainstream rock, both in terms of creativity and technical ability. Learning to play Rush songs was a way for younger musicians to prove their mettle, and as such the band became an influence on a whole generation of rockers, from Dream Theater to Metallica, from Smashing Pumpkins to Stone Temple Pilots, and from Primus to Rage Against the Machine.

Then again, Rush themselves started out in the late Sixties as just another group of teenage hopefuls. Bassist and singer Geddy Lee first met guitarist Alex Lifeson when the two were seventh graders, growing up in the north Toronto suburb of Willowdale. "He was in my class in grade seven," Lee recalls. "He was playing in this band called Rush. It was him, [drummer] John Rutsey and a bass player named Jeff Jones."

Lifeson's band had a regular Friday gig at a coffeehouse run by a local church. "He used to call me up but more to borrow equipment from me than to actually jam, because he was a famous mooch back then," Lee says. "Then he called me up-it was, like, Friday morning-and said, 'Our bass player can't make this gig tonight. Do you want to fill in?'

"I said, 'Sure.'"

Lee quickly went from filling in to playing as a fulltime member. Rush spent their earliest days playing youth centers and high school dances all around Ontario. Then, in 1971, Ontario lowered its drinking age to 18. "We were 18," Lee recalls. "And that opened a whole world of drunkenness to us. And bar gigs."

Over the next two years, Rush slowly built an audience, working their way up the Toronto bar circuit, from tiny Yorkville dives to rock palaces like the Gasworks (which would later cameo as the club in Wayne's World). Along the way, the group picked up manager Ray Danniels, who was determined to build the band into something bigger. "In order to get us out of the bars, he and his partner decided to become promoters," Lee explains. "They started putting on shows at the Victory Burlesque Theatre on Spadina, which is gone now." Their first booking, in October 1973, was opening for the ultra-glam New York Dolls.

Danniels also took a do-it-yourself approach to getting Rush a record deal. He had the band do its recording in the hours after its regular club gigs-studio time was cheaper in the dead of night. When the finished master was turned down by every label in Canada, Danniels put together a label of his own, Moon Records, to release Rush.

Somehow, a copy of the album got to WMMS in Cleveland, where DJ Donna Halper put "Working Man" into heavy rotation. "The phones were going crazy," Lee recalls. Super-manager Cliff Bernstein (Metallica, Def Leppard, Red Hot Chili Peppers), who was then just an A&R man at Mercury Records, picked up on the buzz and got Rush signed. Suddenly, the band had both an audience south of the border and an international record deal.

"And then," Lee says, "our drummer quit." John Rutsey may have been in the band longer, but it was Lee who had forged the stronger connection musically with Lifeson, sharing the guitarist's interest in the more progressive sounds of Yes, King Crimson and Jethro Tull. Rutsey, by contrast, was more of a rock and roll purist, according to Lee. "He was a different kind of rocker, and that was becoming more apparent with the new material we were working on." Worse, Rutsey had no interest in touring, so when the Mercury deal raised the prospect of touring the U.S., Rutsey made for the door.

Needing a new drummer fast, Rush held auditions and quickly found Neil Peart, who at the time had been working for his father's tractor company in St. Catherines, Ontario. Peart may have looked a bit square compared to Lifeson and Lee, but the way he played made it clear that he was on the same wavelength. Peart joined Rush at the end of July 1974, and within a couple weeks was onstage at an arena in Pittsburg, where Rush opened for Uriah Heep.

This new lineup toured steadily through the new year, taking just a week off in January to record its sophomore album, Fly by Night. Although the young band's Zeppelin-isms were still very much in evidence, especially in Lee's muscular, bluesy vocals, the playing was tighter and more virtuosic as Peart's drumming locked firmly with the guitar and bass. Rush toured extensively and did quite a few shows with Kiss, during which the two young bands became close friends.

But where Kiss were moving steadily toward the mainstream, the members of Rush wanted to go in their own direction. Caress of Steel, released just seven months after Fly by Night, pushed the band deep into prog-rock territory, what with the medieval fantasy bound up in "The Necromancer" and a rambling, 20-minute opus dubbed "The Fountain of Lamneth." Where Fly by Night eventually broke the million-seller mark, Caress of Steel was a commercial setback that was mocked by the music press. Although the band continued to build an audience through its live show, its third album was widely considered a step in the wrong direction.

Not by Rush, however. Their follow-up, 2112, continued in the direction of its predecessor, and its success proved that prog was definitely the right path for Rush. As with Caress of Steel, the emphasis was on grand gestures and big ideas, with the sidelong "2112 Suite"-a futuristic fantasy with words by Peart and music by Lifeson and Lee-standing as the band's first avowed masterwork. The album also clicked with audiences, and within a year earned the band its first Gold record.

But 2112 was important for another reason. According to Martin Popoff's Rush biography, Contents Under Pressure, the three members discussed expanding the band's lineup when making 2112 in order to add keyboards and other instrumentation; instead, they decided to double on other instruments. Thus, when it came time for Lifeson's solo in "A Passage to Bangkok," Lee-who would be playing a double-neck Rickenbacker-would switch to rhythm guitar while covering the bass part using a Moog Taurus synth, which consisted of an 18-note pedal board. This early move toward multitasking would later become a major part of the band's performance practice.

2112 was the first Rush album to crack the top 100 of the Billboard Albums chart, but it was All the World's a Stage-a live album recorded at Toronto's Massey Hall that same year-that finally put the band in the Top 40. Perhaps that's why the band felt it could take some time to make its next album, A Farewell to Kings. Recorded over the course of several weeks at Rockfield studios in Wales, the album featured a much broader range of tones than Rush's previous albums, incorporating everything from synthesizer to troubadour-style acoustic guitar flourishes to orchestral bells. Stylistically, it alternated between epic rockers "Xanadu" and "Cygnus X-1" and short, tuneful numbers like "Closer to the Heart."

By this point, Rush were headlining gigs, and they toured mercilessly, often driving as much as 200 miles between gigs (and in those days, the band members still shared in the driving). But their efforts paid off; Farewell sold even better than 2112, thanks in part to the radio play garnered by "Closer to the Heart." The band followed in 1978 with Hemispheres, "probably our most prog album," Lee says. In addition to continuing the "Cygnus" saga with the 18-minute suite "Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres," the album included the nine-minute instrumental "La Villa Strangiato."

Then it was time for something completely different.

Much as punk rock arose in part as a reaction against the perceived excess of progressive rock, 1980's Permanent Waves was meant as Rush's response to the fashion-driven lockstep mentality of late-Seventies new wave. At the same time, it marked Rush's break with heavy prog, as the band's sound grew lighter, less cumbersome and more reliant on synths. Though Rush hadn't exactly simplified their sound-"Freewill," one of the album's most popular tunes, is mostly in 13/4 meter-their focus was definitely different from what it had been previously.

The audience began to change as well. Thanks to the reggae-tinged, Simon & Garfunkel-quoting song "The Spirit of Radio," Rush were finally beginning to develop a pop profile. But it wasn't until the following year, with Movng Pictures, that Rush really hit the big time. Between the pop smarts of the hit single "Tom Sawyer" and the tuneful intricacy of FM-friendly fare such as "Limelight" and the instrumental "YYZ," Rush had come up with the perfect blend of the old wave and the new wave, the epic and the pithy, the visceral and the cerebral. It was the band's biggest-selling album, a quadruple- Platinum smash.

Not surprisingly, this stemmed in part from a change in the band's writing practices. "I started writing parts on keyboards," Lee explains, "just to add more sound, texture and melody. I just thought it would be interesting to bring more noises into the band." But the keyboards didn't simply add "more noises"-they also brought a new sense of space into the arrangements, one that led to changes in Lifeson's palette of guitar tones and Peart's use of percussion.

Exit...Stage Left, the band's second live album, followed quickly, and then it was back into the studio to record the synth-heavy Signals. By this point, rock's new wave had evolved from the skinny-tie simplicity of the Knack to the more complex sound of Peter Gabriel, Thomas Dolby and Ultravox, and Rush's sound seemed to be evolving in tandem. Lee's keyboards often dominated the mix, while Lifeson's guitars turned to chorus and flange more than to distortion. Diehard Rush fans complained mightily about the band's new sheen, but it didn't seem to hurt Rush on the charts. Signals quickly went Platinum, while "New World Man" became the trio's highest-charting single.

By this point, Rush had settled comfortably into the ranks of arena headliners, regularly playing to audiences of 18,000 a night. Although the band would never match the commercial success of Movng Pictures, it would enjoy impressively consistent popularity through the early Eighties, with each of the four albums after Pictures going Platinum and peaking at No. 10 on the Billboard album charts.

That's not to say it was smooth sailing on the creative end. Grace Under Pressure, from 1984, was originally to have been produced by Steve Lillywhite, who had overseen breakthrough albums by U2, Peter Gabriel and Big Country. But Lillywhite bailed out at the last minute, opting instead to work with Simple Minds, which left Rush to coproduce the album with engineer Peter Henderson. Although Grace made significant moves toward restoring the balance between keyboards and guitar (and found Peart experimenting impressively with reggae rhythms), it was nowhere near as polished or confident as its follow-up, 1985's Power Windows, on which the band, spurred by Lee's reinvigorated bass work, played in a much more aggressive style. This time, Peter Collins was behind the board, and his production style seemed perfectly suited to the band's mindset. "We were much more interested in song arrangement and all of that, which is absolutely his forte," Peart told Popoff.

But Hold Your Fire, from 1987, seemed to break that momentum. Some of it had to do with the material, which the band described as "introspective," and which was at points sweetened by strings, additional keyboards (provided by Steven Margoshes) and, on "Time Stand Still," backing vocals (by Aimee Mann of 'Til Tuesday). Mainly, however, it seemed as if another era in the Rush saga was drawing to a close. The band had largely met its obligation to Mercury Records-Hold Your Fire would be followed by a live album, A Show of Hands, as well as the double-disc retrospective Chronicles-and was moving away from keyboards as a central part of the Rush sound.

A Show of Hands did, at least, document the extent to which technology had changed the Rush live show. The three band members had begun using sequencers for some of the songs from Movng Pictures, and by the late Eighties they were making extensive use of samplers to trigger additional instrumental parts. Meanwhile, on the Grace Under Pressure tour, Peart had begun to use the "360 Degree" drum kit, which broadened his percussive range by surrounding him completely with drums and electronic percussion.

For 1989's Presto, Rush moved to Atlantic Records and shared production duties with Rupert Hine (Tina Turner, Thompson Twins). In many ways, the album was transitional: Rush had gained more creative control, thanks to their new label, and had begun taking a new approach to songwriting. Where once the material had been written piecemeal, with melodic ideas stitched together by sometimes hastily written transitions, the songs on Presto were made of whole cloth, more like traditional pop tunes. It wasn't an overtly commercial move-although "Show Don't Tell" did make it to No. 1 on the Billboard Mainstream Rock chart-but it definitely changed the sound and feel of Rush's writing.

Roll the Bones pushed that sense of experimentation further still, with African rhythms sprinkled through the track "Heresy" and even a bit of rap in the title tune, but that hardly phased the fans. Indeed, the album turned out to be the band's biggest seller since Movng Pictures, and the tour-which included a sequence with an animated skull doing the title tune's rap-set a new standard for musicianship and spectacle.

Or course, Rush being Rush, a turn toward pop would naturally be followed by a move in the opposite direction, and so Counterparts shoved the keyboards aside and cranked the guitars, particularly on tracks such as "Stick It Out." But after two decades of releasing an album a year or every other year, the band was beginning to slow down, and there was a three-anda- half-year gap between Counterparts, in 1993, and its follow-up, 1996's Test for Echo.

Not that the band had changed much in the interim. Although Lee spoke at the time of being impressed by Soundgarden and Smashing Pumpkins, Echo was a logical step forward from Counterparts in terms of its sonic aggression and high-impact virtuosity. (It probably didn't hurt that Peart had recorded a Buddy Rich tribute album during the band break.) Perhaps the biggest change had to do with touring practices, as Rush had begun performing two sets, with no opening act.

Then tragedy struck. In August 1997, Peart's teenage daughter, Selena Taylor, was killed in a traffic accident. The following year, his wife died of cancer. Understandably, Rush went on hiatus, and there were some who worried that the band was gone for good.

But the band did return, five years later, with Vapor Trails. "We had a lot of musical reuniting to do," Lee said at the time, and making the album was a long and occasionally awkward process. But it also led to a sense of rediscovery within the band, as each of the three developed a newfound respect for the others' strengths and musicianship. Nowhere was that more apparent than on the subsequent tour, which was memorably documented in the quintuple-Platinum video Rush in Rio.

In 2004, Rush celebrated the 30th anniversary of their record debut with Feedback, an EP of cover tunes, many of which the band had performed in its youth. Feedback was a blast from the past in more ways than one. "We played live on the floor," Lee explains, "which was the first time we'd done that for an album in quite some time. It was just, 'Let's play these songs.'" Naturally, there was a worldwide anniversary tour and, eventually, a concert video: R30: 30th Anniversary World Tour.

By the time the band got back into the studio to make Snakes and Arrows, its 18th studio album, in late 2006, Lifeson, Lee and Peart were back in the old groove. The album was written on acoustic guitar-"the way we used to write, you know, 15, 20 years ago," according to Lee-and emphasized the players' virtuosity while it maintained a sense of song structure. It was, in other words, classic Rush, with every indication of more to come.

Time and Motion

By Chris Gill, reprinted from Guitar World, November 1996

Alex Lifeson Dissects Several Key Songs From Rush's Past

"ANTHEM"

Fly By Night (1975)

"We were trying to be quite individual with Fly By Night, which was the first record that Neil, Geddy and I did together. That song was the signature for that album. Coincidentally, the name of our record company, which is Anthem records in Canada, came from that song. Neil [Peart, drummer] was in an Ayn Rand [author of The Fountainhead] period, so he wrote the song about being very individual. We thought we were doing something that was different from everybody else.

"I was using a Gibson ES-335 then, and I had a Fender Twin and a Marshall 50-watt with a single 4x12 cabinet. An Echoplex was my only effect."

"2112"

2112 (1976)

"We started writing the song while on the road. We wrote on the road quite often in those days. 'The Fountain of Lamneth,' on Caress of Steel, was really our first full concept song and 2112 was an extension of that. That was a tough period for Rush because Caress of Steel didn't do that well commercially, but we were really happy with itand wanted to develop that style. Because there was so much negative feeling from the record company and our management was worried, we came back full force with 2112. There was a lot of passion and anger on that record. It was about one person standing up against everybody else.

"I used the ES-335 again and a Strat which I borrowed for the session; I couldn't afford one at the time. I used a Marshall 50-watt and the Fender Twin as well. I may have had a Hiwatt in the studio at that time, too, but I think it came a little later. My effects were a Maestro phase shifter and a good old Echoplex. There were a limited number of effects available back then. The Echoplex and wah-wah were staples in those days."

"LA VILLA STRANGIATO"

Hemispheres (Polygram, 1978)

"We wrote this one on the road. We used our soundchecks to run through songs that we were going to record; then, when we would have a few days off and start recording. This song was recorded in one take, with all of us in the same room. We had baffles up around the guitar, bass and drums and we would look at each other for the cues. My solo in the middle section was overdubbed after we recorded the basic tracks. I played a solo while we did the first take and re-recorded it later. If you listen very carefully, you can hear the other solo ghosted in the background. That was a fun exercise in developing a lot of different sections in an instrumental. It gave everyone the chance to stretch out.

"By that time I had my ES-355, and my acoustics were a Gibson Dove, J-55 and a B-45 12-string. I had my Marshall in the studio. I had the Twin and two Hiwatts, which I was also using live, but the Marshall was my real workhorse. The Boss Chorus unit had just come out at that time, but I think I used a Roland JC-120 for the chorus sound here. Hemispheres was the first of many 'chorus' albums."

"THE SPIRIT OF RADIO"

Permanent Waves (1979)

"There was a radio station here in Toronto-it's an alternative station now-and 'the spirit of radio' was that station's catch phrase. That song was about the freedom of music and how commercialized radio was becoming. FM radio in the late Sixties and early Seventies was a bastion of free music where you got to hear a lot of things that you wouldn't have heard otherwise. It was much like MTV was in the beginning, before it became another big network that feeds a large but very specific segment of the viewing audience. Radio has become a lot more commercialized since then. Now, the station that we wrote that song about won't play our music.

By the time we cut this, I was using mainly a Strat that I had modified by putting humbuckers in the bridge position. I also used the 355, which I used in the studio for the next couple of records. My amps were Hiwatts, the Marshall and the Twin. I also had a Sixties Bassman head and cabinet. The flanger on that song was an Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistriss, which I still have. I used the Boss Chorus Ensemble, and I had graduated to the Roland Space Echo, which replaced my Echoplex."

"LIMELIGHT"

Moving Pictures (1981)

"'Limelight' is about being under the microscopic scrutiny of the public, the need for privacy-trying to separate the two and not always being successful at it. Because we've never been a high-profile band, we've managed to retain a lot of our privacy. But we've had to work at it. Neil's very militant about his privacy.

"My guitar was a different modified Strat with a heavier and denser body. We set up a couple of amps outside of the studio as well as inside, so we got a nice long repeat with the echoing in the mountains. The approach on that solo was to try to make it as fluid as possible. There was a lot of bending with lots of long delay repeats and reverb, so notes falling off would overlap with notes coming up. I spent a fair amount of time on that to get the character, but once we locked in on the sound, it came easily."

"NEW WORLD MAN"

Signals (1982)

"Most of Signals was completed, but we wanted to add one more song. Neil had been fooling around with the lyrics, so we wrote and recorded 'New World Man' in the studio within one day. It has a very direct feel. Doing that in one day was a lot of fun. The pressure was on but off at the same time.

"It was almost compulsory to do solos at that time, but I didn't want to feel that every song had to have that kind of structure. I wanted to get away from that, and to this day I feel that way. I enjoy playing solos and I feel that my soloing is quite unique to my style, but I'm bored with that structure.

"I used a Tele for the whole song. I played it through the Hiwatts with a little bit of reverb and chorus."

"THE BIG MONEY"

Power Windows (1985)

"That was a tough one that took a long time to complete. It was recorded in Montserrat. The guitar was tuned up a whole step with the E string at F#, and I played a lot of open chords. I did a lot of drop-ins where I hit a chord and let it ring, then dropped in the next chord and let it ring and so on. When we started recording the song, it sounded too ordinary, so we tried dropping in those chords during the verses as an experiment.

"I remember doing the solo in this studio in England, SARM East, which is in the East End of London. We set aside a week for solos, last-minute vocals and mixing. The control room was tiny; there was barely enough room for me to turn my body around when I was playing, but I got a really great sound with the repeats and lots of reverb. I loved to be soaked in that kind of effect at the time.

"I used a white modified Fender Strat that I called the 'Hentor Sportscaster.' The name came from Peter Henderson, who co-produced Grace Under Pressure. The amp setup was a couple of Dean Markley 2x12 combos, two Marshall 2x12 combos, two Marshall 100-watt JCM 800 heads and two 4x12 cabinets. I also ran a direct signal. By that time I had a pretty comprehensive rack with two TC Electronic 2290s and a 1210 that I used for phasing, and I had a Roland DEP-5."

"TIME STAND STILL"

Hold Your Fire (1987)

"We were in a bit of a reflective period at that time. Everything seemed to be moving by very quickly. Aimee Mann [then bassist and singer with pop group 'Til Tuesday] came up and did vocals in the chorus of that song. It was a lot of fun to work with her. She was very nervous. I don't think she had done that sort of thing very often, especially with a a band like us. We weren't necessarily playing the kind of music that she was into or listening to, but she liked the band. We made here feel relaxed very quickly, turning the whole session into a fun thing.

That was the year that I got the Signature guitars with single-coil active pickups. It's very apparent on that song. The guitar has a clear, metallic sound to it that really sings. I got into that bright tone, and my sound was still very chorusy. I had gotten rid of all my Hiwatts and the Dean Markleys and was using primarily Marshalls again. I used 2x12 combos as well as the JCM 800."

"Show Don't Tell"

Presto(1989)

"By then we were working with Rupert Hine as our producer. Oddly enough, I had been working on the basic ideas of that song at home and brought it to the studio when we started writing the record. We developed it from there. It was much heavier in the early version; the tempo had come up a little bit. Rupert's approach to the guitar sound was a little lighter than I wanted. That was partly my fault, because I was still using the Signature a lot, which didn't lend itself to a very thick sound. That amp lineup stayed the same as before, and effects would come and go. I was fiddling around with whatever was new at the time, as I've always done.

"We'd taken a seven-month break, which at that time had been our longest hiatus. We needed to clear the cobwebs and get away. We came into Presto feeling a lot more enthusiastic about working. The change to Atlantic Records was good because we felt like we needed a change all around. We were going into the Nineties, and it made everything fresher."

"Stick It Out"

Counterparts (1993)

"I USED A Peavey 5150 and a 100-watt Marshall JCM800. I had a [Roland] JC-120 as well that I used for some clean things, but primarily everything was done on the Peavey and the Marshall. The guitar was a '72 Les Paul Standard that I had used on certain songs in the past. I used a dropped-D tuning and ran the guitar straight into the amp with no effects.

"We had gone back to working with Peter Collins, who produced Hold Your Fire. We used a much more direct approach to recording, moving back towards the essence of what Rush was about as a three-piece. In retrospect, Counterparts didn't work as well as we'd hoped, but it led us in the right direction. We're much more satisfied with Test For Echo, which we view as a progression from Presto."

"Test For Echo"

Test For Echo (1996)

"There's a lot of different stuff on there. I tuned the entire guitar down a whole step to a D standard tuning. I got a new Les Paul Custom with beautiful sustain, a heavy tone and a compact, but not too small, sound. In the choruses I used a Godin Acousti-Caster, which has a really interesting sound that is at the same time almost acoustic but definitely electric. I used primarily Marshalls-50-watt and 100-watt JCM 800 heads and two 30th Anniversary models-with four cabinets: two vintage 4x12s and two new 1950 cabinets with Celestion 25-watt speakers. I used a DigiTech 2101 to knit everything together. The important thing with that is to use it through a good speaker simulator, like the Palmer. The compensated outputs on the 2101 don't quite do it for me, but through the Palmer it has nice body and width.

"I feel like we've arrived with this record. There's a particular feel that I don't think we've had before, a nice groove and a lot of really good Rush songs. I feel like we were all really together on this album. Although we strive for that all the time, it's not always achievable. The mood was so good in the studio, and we were so unified in direction."

Vital Signs

By Joe Bosso, reprinted from Guitar World, August 2007

As Rush drop their latest release, Snakes & Arrows, guitarist Alex Lifeson reflects back on Moving Pictures, the prog-rock masterpiece that gave life to the power trio's legend.

If you were a teenage male in the Seventies, the chances are very good that you had long hair and a wispy moustache and went to rock concerts with a doobie in your back pocket. And the chance is even better that the band you went to see was Rush. Back in their heyday, guitarist Alex Lifeson, bassist Geddy Lee and drummer Neil Peart effected a Jedi warrior sci-fi look straight out of the then-newly released Star Wars film. No doubt the first image you glimpsed of Lifeson was that of a mythical-looking rock god with a blond Prince Valiant do, resplendent in satin scarves and capes and wielding his Alpine White Gibson EDS-1275 double-neck on such space-rock classics as "Xanadu" (no, not the Olivia Newton-John hit, although that would have been interesting). Lifeson cut quite a figure in those halcyon days, especially when bathed in orange-and-yellow lights as he soloed before a backdrop of the "starman" logo taken from the back cover of Rush's science-fiction opus, 2112.

But the Alex Lifeson who sits before me in the Guitar World offices bears not a soupcon of that enigmatic, angelic presence. "I feel like I have little connection to that person at all," he says, between sips of bottled water. Now 53, he's still blond, though his close-cropped hair is flecked with gray. "And I've lost some in the back," he says, leaning forward to display the lamentable evidence of male-pattern baldness. "I couldn't grow that Peter Frampton hair again if I tried. Come to think of it, Peter Frampton can't grow Peter Frampton hair anymore!"

Refreshingly devoid of rock-star vanity ("Rush has never been a band of pin-ups, thank God!"), Lifeson brims with good cheer and is big on eye contact. "It's a fabulous time in my life," he says. "In July I'm going to be a grandfather again, which thrills me to no end." (Lifeson already has one grandchild from his second son, Justin.) "It might not be very rock and roll of me to say, but I love being a grandfather. Love it, love it, love it."

He pauses briefly, becoming reflective. "The thing is, I don't take anything for granted anymore-my family, my music, you name it. Unfortunately, it took Neil's tragedies to teach me that."

The tragedies he's referring to are almost unbearable to consider. In 1997, Peart's daughter and only child, 19-year-old Selena Taylor, was killed in a car accident. Less than a year later, his common-law wife of 22 years, Jaqueline Taylor, succumbed to cancer. "Neil was 44 years old and his life was over," Lifeson says softly. "How do you come back from that? Geddy and I didn't know what to do, other than to be there for him and give him his space."

As it turned out, Peart needed a lot of space. Music, which had always been the drummer's anodyne, offered little solace. "Neil told us, 'Consider me retired,'" says Lifeson, "and in a way, we had to take him at his word." Peart set out on a two-year, 55,000-mile motorcycle trip back and forth across North America (documented in his book Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road). Eventually, his travels took him to Los Angeles, where he met his future wife, photographer Carrie Nuttall. The two married on September 9, 2000. Not long after, Peart called his band mates to tell them he was ready to give music another go.

"We were thrilled for Neil on so many levels," says Lifeson, "and of course we were ecstatic that he wanted to get the band back together. But it was tough. He hadn't touched the drums in years, and when he finally sat down at the kit, I'd say he was one-tenth the drummer he used to be-still pretty great, but there was a long way to go. However, we weren't putting any time restrictions on him. When he was ready, so were we."

In 2002, Rush released Vapor Trails, their first album in six years. A brave, although at time tentative album, it saw the band embracing, as always, odd meters (the song "Freeze" alternates between 6/4, 5/4 and 4/4) but eschewing keyboards and guitar solos. "We felt the record should be as natural as possible," says Lifeson. "We were learning to be a band again. That can be hard to do when you're getting on in years and you've been through hell."

A middle-aged Rush needn't be a bad Rush, and the band's bold new album, Snakes & Arrows (Atlantic), should be greeted with hosannas by the faithful. Produced by Nick Raskulinecz, who helmed the Foo Fighters' One by One and In Your Honor, it sees the Canadian trio stoically refusing to become part of the ancien regime of prog-rock. The slamming, riff-heavy first single "Far Cry" immediately joins the ranks of Rush's finest pop offerings. Interestingly, however, the record's most rewarding moments are also its most frustrating. On acoustic-based tracks such as "The Larger Bowl" and "The Main Monkey Business," Rush provide the musical answer to filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard's theory of filmmaking-that a story must have a beginning, a middle and end, but not necessarily in that order. "Workin' Them Bones" features some of Peart's most heartfelt, straight-forward lyrics ("No one gets to heaven without a fight"-hey, he knows). As sung by Geddy Lee, whose upper-register wail has deepened with age, the words hit you where you live.

Snakes & Arrows serves up a veritable smorgasbord of Alex Lifeson guitar styles, but perhaps the biggest surprise is 'The Way the Wind Blows,' in which he displays his penchant for pure, unadulterated blues soloing. 'That's probably the last thing people expect from me, which is why I did it,' Lifeson explains. 'When I hear that sound, I feel like we're a new band, just like we were when we made Moving Pictures. You know, people didn't expect that sound from us either.'

Moving Pictures. An intoxicating, exhilarating marriage of planetarium-like prog-rock madness and new wave spunk. It's been 26 years since the release of the synapse-altering album that introduced Rush to the mainstream, and Lifeson marvels at its longevity. 'It's become one of those 'Desert Island Discs' to a lot of people,' he says, 'which is a huge compliment. I'm very proud of that record. And to be quite honest, if we never made Moving Pictures, I probably wouldn't be sitting here right now talking about our new album. Certain records are epochal; they're a zeitgeist unto themselves. For us, Moving Pictures was it. Hopefully, we'll have a few more.'

GUITAR WORLD Before we talk about the new record, let's revisit Moving Pictures. While recording it, did you have the slightest idea how popular it could be?

ALEX LIFESON Not at all. Did we think we were doing great work? Absolutely. But you never think, In 26 years this album will still be selling 15,000 copies a week. No way.

GW At the time, how influenced were you by new wave? Many of the songs on the album are short and poppy, at least by Rush standards, and your guitar sounds bear certain similarities to that of Andy Summers.

LIFESON I was very influenced, in many ways. I cut my hair! [laughs] That shocked a lot of our longtime fans who were used to my long, flowing locks. Also, I started dressing cooler, more au courant, wearing bright, colorful blazers and ties. I didn't look like I'd just come from a Renaissance fair. [laughs]

It was time for all of us to change, musically, visually-our entire attitude. The songs got shorter, more accessible. It felt good to become a bit of a new band. We were listening to the Police, and their impact was huge. We saw that a rock trio could do so many different things.

GW However, a hint of that impact was apparent on Permanent Waves-the reggae break in 'The Spirit of Radio' and on 'Vital Signs,' from Moving Pictures.

LIFESON Yep. That was early Police influence. Their rhythms, their sounds- It was as exciting as when Cream came out. For us, it was a matter of using those new wave influences in ways that enhanced, but didn't degrade, what we were doing.

There was the Edge too. What he did with the echo pedal is beyond measure. Yeah, the Edge and Andy Summers were very high on my list in those days. Still are.

GW What's interesting is, in 1981, both Rush and the Police became enamored with synthesizers: Rush on Moving Pictures, and the Police on Ghost in the Machine.

LIFESON Great minds think alike. [laughs] When Geddy got into keyboards, it just seemed like a natural progression. We were trying to expand our sonic palette. Like the Police, we didn't want to be limited by the power trio paradigm.

GW It must have been hard for Geddy to play both bass and keyboards at the same time. Did you ever think of adding a fourth member?

LIFESON No, never. Geddy had everything under control, even though he had to be a bit of an octopus at times. I was operating foot pedals too. God, I had to dance around like crazy.

GW You're just a bunch of Fred Astaire-type multitasking fools, huh?

LIFESON You said it! [laughs] If there was a harder way of doing things, that's what we did. But while making Moving Pictures, I remember thinking to myself, The guitar is pretty much the dominant sound of the band, so why am I working so hard at it? Using effects and making my sound more processed enabled me to explore space and different textures; it freed up our sound and, more importantly, our songwriting. It was a very fun time. You have to understand, we'd done the 20-minute science fiction opuses. It was getting boring.

GW Even so, Rush have always been labeled as 'cerebral' rockers-that is to say, not Van Halen. Did that ever bother you?

LIFESON No. [laughs] My God, no. The fact that we don't write songs about getting laid on Sunday night- That's never been us.

GW Wait a minute: who gets laid on a Sunday night? That's back-to-work night!

LIFESON Now there's an idea we might be able to explore. [laughs] No, but see, even though we have no problem with the rock and roll lifestyle, Rush have always been about musicianship. If that makes us 'cerebral,' fine. Also, I think as Neil has developed a lyricist, our music became more poignant. The thing about Rush is, we have fun, even though we look like we're not. [laughs]

GW Did having a big hit with Permanent Waves add to any pressure while recording of Moving Pictures?

LIFESON Not at all. We were cruising! We had the wind at our backs and we were having fun. Perhaps that's why it's one of our most famous records: people can tell when a band is on fire, and we were, boy.

GW What guitars did you use on the album?

LIFESON My mainstays: a Gibson ES-335, a 355, my Howard Roberts Fusion guitar and my Sportscaster, which is a Strat that I modified with humbuckers, a Floyd Rose and a Shark neck. The body is the one Strat component that remained.

GW Tell me about the solo in 'Tom Sawyer.' How long did that take to work out?

LIFESON I winged it. [to my astonished face] Honest! I came in, did five takes, then went off and had a cigarette. I'm at my best for the first two takes; after that, I overthink everything and I lose the spark. Actually, the solo you hear is comped. Most of my solos are comps, now that I think of it.

In truth, yes, I had an idea of what I'd play, but I don't get married to ideas for solos during the writing; that's how performances gets sterile and formulaic. Of course, the irony is, once I record a solo, that's what I wind up having to play the rest of my life! [laughs]

GW Anybody's who's listened to the radio for the past 26 years knows the opening riff to 'Limelight.' That's one of those it's-so-simple-it's-genius licks.

LIFESON Thanks. I got lucky that day. How these riffs appear is a mystery. I remember that we had the song pretty much mapped out, and there is a pre-chorus section where I play chords that are very much like the riff. I think what I ended up doing was just simplifying it for the opening. We knew we needed to kick the song off somehow.

It's funny: after all these years, the solo to 'Limelight' is my favorite to play live. There's something very sad and lonely about it; it exists in its own little world; and I think, in its own way, it reflects the nature of the song's lyrics-feeling isolated amidst chaos and adulation.

GW 'YYZ' has gone on to become one of the band's best-loved instrumentals.

LIFESON And that came from just jamming. As you might know, the initials 'YYZ' is a transmitter code for the Toronto International Airport, and what we did was open the song in a 10/8 rhythm, which is actually Morse code for those initials. It's a weird thing: People expect Rush to have an instrumental on every album-I guess because we're known as 'musician's' musicians-but that's not how we operate. Neil can usually make lyrics fit any kind of rhythm or chord arrangement, so for us to turn a song into an instrumental, it has to be because we feel that's what the song is meant to be.

GW Let's talk about the new album, Snakes & Arrows. Aside from his hard-to-pronounce last name, what made you decide to work with producer Nick Raskulinecz?

LIFESON Well, that was the reason: his name. [laughs] I relate to him, for obvious reasons [Lifeson's given surname is Zivojinovich]. Originally, we talked to a few producers, but the vibe wasn't there-not totally. And then I guess Nick heard we were getting close to recording, and he told his management, 'I've gotta do it! No matter what, I have to work with Rush. Get me a meeting!' Crazy, genuine enthusiasm: we'll take it. [laughs]

Nick flew up and met with Geddy and me. He had such exuberance and true passion for making music-a real thoughtful guy whose energy was infectious. Geddy and I looked at each other, and we could tell we'd have a good time working with him. And we were right: there wasn't a single moment of tension or stress throughout the recording; every day was a joy to go to work.

GW But is that necessarily a good thing for making an album- Doesn't a little dramatic tension push you out of comfort zones and into unexplored areas?

LIFESON I know what you mean. One doesn't want to feel too contented; you have to feel challenged by the music. But Nick did push us, sometimes in ways we never expected.

GW How did he push you as a guitarist?

LIFESON [very long pause] This is tough? See, I was so focused-I'm not saying the other guys weren't-but because this album was written on the acoustic, I was so hot going in. You know how we talked about Moving Pictures and how I'd play solos cold? This record was the exact opposite: I knew exactly what I wanted. Writing a lot of the songs on the acoustic offered me a wonderful way to sketch out the album; I knew that if everything worked on the acoustic, everything would be ten times more powerful on the electric.

GW Do you guys cut proper demos before recording the actual album?

LIFESON Oh yeah. Our demos sound like pretty good records. Geddy has a Logic recording system in the writing room in his house, and we go in there and work things out. By the way, he lives five minutes away from me. Can you believe that after 40 years we live so close together?

Anyway, we have a great system for writing: we work three days a week from noon till six o'clock; then we play tennis or hang out with our families. A lot of times we go out to dinner after our writing sessions and talk about what we've done. A very relaxed pace.

We tracked the record at this wonderful place called Allaire Studios in the Catskills. It's a great studio with tremendous views of the mountains. Very inspiring. Nick came up and threw himself into the situation. A few songs we didn't touch at all, some songs we moved a few things around, and there was one song called 'Spindrift' that we made radical changes to. We were very impressed with Nick: he wasn't afraid to tell us that we had the song all wrong. Most producers are afraid to do that with name bands. Also, he allowed us to rerecord anything we wanted, as many times as we wished. A lot of producers these days just want to Pro Tools parts together.

GW Obviously you have a pantload of guitars. How many did you bring to the studio?

LIFESON [laughs] A 'pantload'-that's funny. I didn't bring too many, actually. My acoustics were a Gibson J-55, a Larrivée, and I also used Garrison six- and 12-strings. As far as electrics, I think I mainly used my Tele, my ES-335 and this fantastic Les Paul Goldtop reissue I have. I tried to keep things relatively? simple.

GW As you said, the dominant sound on the album comes from acoustic guitars.

LIFESON Yeah. I was playing a lot of acoustic before making the record and my heard was stuck in that world. Plus, I had recently seen [Australian fingerpicker] Tommy Emmanuel and [harp guitarist] Stephen Bennett perform, and I was very taken with what they were doing. In fact, Stephen gave me a half capo, which I'd never seen before, and I thought it was really cool. You can move it around but still have open strings. What an awesome little thing! I used it on the song 'Bravest Face.'

GW 'Far Cry' has a very strong riff. How did that come about?

LIFESON Geddy and I were jamming, and one day I found myself playing it. [laughs] Again, that's the magic of making music: One day you have nothing, and the next, it's all there. I feel as though it really can't be explained.

GW I expected a big solo on that song, but instead you went for a feedback section.

LIFESON Yeah, I heard these sirens in my head, so that's what I decided to do. Geddy plays the riff underneath the feedback. Another song where there's no solo is 'Workin' Them Angels,' and what happened was, I originally recorded a solo over this section of very Celtic-sounding mandolins. It was a cool solo, nothing wrong with it, but just before we mixed the album, I called Nick and said I didn't think the solo was necessary, that it sounded better with just the mandolins. I was prepared for a big disagreement, but Nick was like, 'Dude! Absolutely. I was thinking the very same thing.' [laughs] I hate to disappoint guitar fans who are waiting for solos, but sometimes you just don't need them.

GW However, you do play a beautiful solo in 'The Larger Bowl.' What guitar are you using on that?

LIFESON That's my Tele. There are a lot of acoustics underneath, so when we play the song live, I might have to trigger samples so it doesn't sound as naked when I do the solo.

GW The instrumental 'The Main Monkey Business' is, for the most part, a real acoustic opus. Was that your song that you brought to the other guys?

LIFESON No, not really. We wanted to do an instrumental that had some real substance, but we were getting pretty deep into finishing the record. So one day we started jamming, and the song started to emerge. At first, it was extremely complicated-it probably had about twelve different parts to it-and Nick really helped us whack it down and simplify it. The only problem is, to play the song live I might have to bring out the double-neck. I think I can put piezos in it to approximate the 12-string acoustic sound. [rolls his eyes] Man, I dread it though; that thing weighs a ton! You feel it the next day in your neck and shoulders. Maybe I'm just getting old.

GW You guys have been together for so long. Tell me, have you ever had a good slugfest?

LIFESON [laughs] No, no, no. But it's come close. We don't always see eye to eye; we squabble. Back in the old days when we were touring 10 or 12 months out of the year, my God, you get sick of each other. The slightest little thing one guy does can just set you off. But at those times when we do fight, five minutes later we're saying, 'Shit, I'm sorry, man.' We love each other, we love hanging out together, and we really love playing music together-after all these years!

Happy Trails

By J. D. Considine, reprinted from Guitar World, August 2002

In 2002, after weathering several years of unspeakable emotional upheaval, the members of RUSH found solace and uplift in creating Vapor Trails, their most powerful work in years.

"Let's throw the clock out the window on this project."

That, says Geddy Lee, was the goal when he and the other members of Rush-guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer/lyricist Neil Peart-began work on Vapor Trails. The band's 17th studio album, it's also the first new material the Canadian trio has produced since Test for Echo in 1996-a dry spell long enough to have left some fans worrying if the band was ever coming back."

It was a reasonable concern, given the personal trauma the group had been through. On August 10, 1997, a month after Rush had wrapped their Test for Echo tour with a triumphant, three-hour show in Ottawa, Peart's 19-year-old daughter, Serena, was killed when her Jeep ran off the highway and crashed, in Blighton, Ontario. Less than a year later; Peart's wife, Jacqueline Taylor, was dead of cancer. The band managed to assemble a live album, Different Stages, from the Test for Echo tour in 1998. But the three musicians still hadn't played together since that night in Ottawa.

During that downtime, bassist Lee cut his first solo album, last year's My Favorite Headache, and Lifeson produced an album for a young Pennsylvania band called Lifer. Peart, meanwhile, maintained a purposely low profile, traveling by motorcycle from Alaska to Mexico and trying to regain his emotional equilibrium. When the group finally got back together in January 2001 to begin work on a new Rush album, the members were, as Lee dryly notes, "in very independent head spaces."

"We had a lot of musical reuniting to do," he says. "There was a lot of air to clear, a lot of emotion floating around the control room, it took time to sort all those feelings out and get to a point where we could look at each other and know that our comments to each other-critical and otherwise-were being taken correctly."

Although Lee worried at first that the three would end up "biting each others' heads off," the sessions turned out to be anything but acrimonious, It wasn't just a matter of being sensitive to Peart's situation; the work Lee and Lifeson had done outside of Rush had brought the two a new set of skills as well as newfound respect for each other's abilities,

All of which is reflected in Vapor Trails, the strongest, most dynamic Rush album in decades. While the writing reflects the same melodic focus that pushed 1991's Roll the Bones and 1993's Couterparts into the Billboard Top 5, the playing is fiery and inventive. From the hell-bent-for-leather gallop of "One Little Victory" through the roiling interplay of "Peaceable Kingdom" to the deftly shifting textures of "Out of the Cradle," the band plays brilliantly, marrying prog sophistication to punk intensity. All told, it's Rush's most radical stylistic shift since Moving Pictures, two decades earlier.

We sat down with Lee and Lifeson at the Toronto offices of Rush's Canadian label, Anthem Records. (Peart, understandably, decided to sit out this album's interview cycle.) Despite having spent 13 months on Vapor Trails-more than twice as long as the group typically spends writing and recording-the two seemed relaxed, content and more than slightly proud of the work they'd done,

GUITAR WORLD After 23 straight years of writing, touring and recording, you guys find yourselves in a situation where you haven't; played together in nearly four years. Not only that, but; you were processing some pretty intense emotional experiences. How do you start working in a situation like that?

GEDDY LEE We talk. We talk a lot about what kind of music we want to write. That's kind of the first thing, and I really think that without that conversation, none of the rest can follow. It takes us awhile to really talk it through, and we do a lot, a lot of talking before we start writing anything. We talk about what kind of music we're getting off on, about whether there is a direction we haven't gone before, whatever.

Amazingly, we had few scraps 0r disagreements. There were a lot of discussions, but it was incredibly conciliatory. [laughs]

GW Was that because you'd gone so long without spending time together'!

LEE I think it's because there was a great deal of respect for each other. After all of the difficulties of the last number of years, when we came and looked at each other-and we looked at each other as friends-there was a great feeling of affection, because we had been there for each other through this tough time. And there was also a great respect for each other's abilities. It kept us in a nice place. I don't know how to describe it other than that.

ALEX LlFESON Yeah. Like Geddy says, we've been friends forever. When we started, I saw how much he'd gown, through the experience of doing his own record. And that's hard to do, a solo record. So much is on the line, and you're responsible for everything. He cameinto this project with all this confidence, and such an elevated sense of music. I felt for the first time in our whole working relationship that I could leave the room and trust him 100 percent. I was guided by a lot of things that he was doing. Pushed my ego back a little bit, and pursued the things that I felt I had strength in.

Most of the arranging, Ged did that on his own. He'd say, "Leave it with me for a couple hours." I'd go, and play guitar or hang out. And every time I listened to something that he did, it was, "Yeah. Fuck, it's perfect. That's great." I can't tell you how great that felt, going home every night knowing that I didn't have to worry about those things.

LEE [laughs]

LlFESON I mean, our relationship just locked like this after the first couple of months.

LEE I don't think we ever had such a solid partnership on any record. Maybe not since 2112 have we been able to understand each other, see each other clearly, our strengths and weaknesses. It was the same thing when Alex would say, "I want to do guitars tonight." I would say, "Okay, check you later. Have fun." And he would go, and he would just experiment, and we would talk about things the next day. And when Neil was getting all his drum parts together and starting to get his confidence back, Alex was there every minute, helping him get his drum sounds together, engineering the session. It was really incredibly hands-on, and we became each others' producers. It was really cool that we could do that.

GW How did the writing start? Did anybody come in with stuff already written?

LEE No, we had a clean page, basically. We set up in a small-small-ish-studio. We set Neil up in the playing part of the room, and we had a writing setup in the control room. Plus Neil had a room that he could go in and work on lyrics. So as Alex and I were getting to know each other again, Neil was slowly getting his playing chops, because he had not played. He was well out of it and had to build up his hands, his physical endurance.

GW You say it was a writ ing setup--did that mean you just sat around with acoustic guitars and a notebook?

LlFESON I had an amp set up in the studio, enclosed in a type of cabinet I use live, which we call doghouses. They're lead-lined, completely isolated. I moved that into one of the isolation booths after a while and just opened up the cabinets. Geddy runs direct, and we used a drum machine for the writing process. And there are basically no keyboards on this record.

GW Wait a minute-isn't that harpsichord on the beginning of "How It Is"?

LlFESON No.

LEE That's mandala.

GW A mandola?

LlFESON It's like a large mandolin. It's got 10 strings. I just took it out one day and said, "Hey, how does this sound?" We got ofT on it so much that we started putting mandala on all sorts of songs. It just has that bell quality to it, and depending on how you tune it, you can bring out all kinds of different sympathetic notes, and ringing and buzzing and all of that.

LEE He would play some of them with picking, and some of them by rubbing the strings and creating kind of a shimmery sound. And we'd meld those together to give it kind of a unique tone. Our basic setup in the writing system is to have everything sound as if you were making a record. And we had a Logic Audio digital recording setup, so even when we're jamming, we're jamming over four or five tracks, and keeping everything. Then we would listen back later, and see if there were sparks there that could become something. That was the goal: to create a comfortable writing environment so that when Alex and I jammed together and got off on it, we could make that into a song-and keep the original performance if the sounds were good. A lot of times they were close, and close enough to say, "Well, the performance is more valuable than 10 more percent on the guitar sound, so let's keep it."

GW And with a computer-based system like Logic Audio, you can do all sorts of editing with those bits.

LEE Oh, yeah, you can do whatever. You can just take that and go crazy. Which I have a tendency to do.

LlFESON Thank god! [both laugh]

GW Okay, so you and Alex jam, and you take all the good bits and assemble them into basic tracks that eventually become songs. But it's just music at that point. When do the lyrics come in, and how?

LEE What happens is, I get these bits of paper from Neil, with lyrical ideas. I read through them, and I either relate to them, or I'm inspired by them, or they leave me flat. And I kind of prioritize my pile accordingly. Then, after we jam, I'm attracted to certain things and I'll just start constructing a song that way. It's really a question of what strikes me lyrically, because I have to sing these songs. I'll sit down with some lyrics and go, "These lyrics are my script, and I have to make them come to life." I'll put a chordal structure together, and a melodic thing-just get lost in it, and try to express it.

Then sometimes it's the other way around, where we've got these bits of music and think, "Fuck! There's nothing here in the lyrics that suits that. Ther e's a real strong vibe, there's a song waiting to be born here, but it's not going to be born with these lyrics." Then we'll put it down on tape and give it to Neil. In which case, he'll listen to it until he thinks he has something. It goes back and forth like that.

LlFESON Yeah. And that could take a long time. Months.

LEE On this record, it was exceedingly difficult to be happy with what we did, and I think a lot of that was because of the gap---six years between projects, plus all the emotional upheaval in everyone's life. Particularly Neil's life. Things had to move slowly on this project. I think we all realized that. You can't control a rate of healing.

But I realized as we were mixing it that the longer you spend making a record, the harder it is to finish it. The more time you invest in something, the more important it feels. It's just hard to have that casual attitude. [chuckles] The casualness goes away after you spend a year or your life on something.

GW Given the situation with Neil's personal life, I'm sure a lot of fans are going to be looking for the tragic, life-has-stomped-down-on me song. But the closest thing to that I hear on the album is "Nocturne."

LEE Well, "Nocturne," "Ghost Rider," "Sweet Miracle," even "Secret Touch," I think, are all related to some sort of realization. I think they're all rooted in his experience and talk about his need and his ways of climbing out of it. For me, singing those lyrics, I have to be able to make them universal. I have to find a way in.

And that was a tough thing. That was a lot of going back and forth, and taking a personal experience and trying to accept it and understand it and want to express it, but in a way that felt good, felt right for me to sing, and felt like there was enough in there so that someone else would not be weirded out by the intimacy of it.

GW It must be not just a balancing act but something you can't do unless you are very comfortable with the other person.

LEE Yes. Exactly. Exactly. And it was an amazing personal experience for the three of us, because of that.

GW Okay, so you and Alex assembled these jams and bits of melody, all while working to a click track. So when did you play with Neil'!

LEE We didn't. It was almost all pieced together.

GW You did the whole album to click track?

LEE We weren't going to do that originally. We had set aside time to go back and play all this stuff live. Basically, Neil was learning the songs with a click track, and just. getting in shape, getting his parts together. But before we kl1ew it, he had nailed them all. He was just nailing them.

So we would say, "Is there any value in playing this all over again live?" And we decided there wasn't. Because it was there. We were getting off on it, it sounded right. It didn'tsound overdubbed, it didn't sound piecemeal.

GW In recent years, a lot of big-time alt-rock musicians, from Billy Corgan to the members of Stone Temple Pilots, have testified to the major role that Rush played in their musical upbringing. The complexities of your tunes and your arrangements have been a touchstone for a generation, and yet Rush get no props from the critical establishment, and none of the respect given to acts like the Police or Steely Dan. It's like people just don't want to give Rush their due.

LEE Yeah, that's true. I don't know why that is. Maybe it's that we've never really broken into the mainstream. We could be the world's most popular cult band. Like Black Sabbath, which to me was fairly mainstream metal when I was growing up.

GW Right. Everyone knew Black Sabbath's music, but you wouldn't hear it in a supermarket.

LEE And you wouldn't hear us in the supermarket. Unless it was a really weird supermarket.

LlFESON I don't know. I was in Canadian Tire awhile ago, just after Tool's last album came out, and they were playing "Schism" in the Canadian Tire, which is like a big hardware store.

LEE But it's Tool, and they sell tools. [laughs]

LlFESON Maybe that's what it was! But I think Geddy's right, and if we've influenced that generation of bands or musicians, it's because they look at Rush and think, Well, here's a band that wasn't popular in a mainstream way, yet they've been around for 30 years. This is proof that we can stick to what we believe is right for us and not worry about radio or pressure from record companies.

LEE I think that's what inspires bands. And, you know, our music has largely been players' music, and a lot of bands are influenced because that's how we start out, as players. A lot of young players cut their teeth on our music because it's hard to play, and yet it's not jazz, so it's still accessible.

There's always been a bit of a bias against us from critics, because they just don't get it, and maybe because they're not players. They've thought our music was pretentious, that our reach exceeded our grasp, or whatever. Maybe the nature of Our lyrics put them off.

GW One last question: Why no "u" in Vapor Trails? I mean, that would be the Canadian way to spell it.

LEE That's an argument I was not prepared to have with Neil.

LlFESON Yeah, we were both on the "u" side, the proper English spelling.

LEE I used the "u" on my album, My Favorite Headache, for Britain and Canada: My Favourite Headache. But Neil tends to the U.S. He likes the simpler spellings. So I'd put the "u" in there, if it were left to me. But I'm not fighting for a "u."

Living In The Limelight

By Andy Aledort, reprinted from Guitar World, January 1999

Alex Lifeson demonstrates key licks from "Tom Sayer," "Limelight," "Closer To The Heart" and more, as he and Geddy Lee discuss Rush's 1998 live album, Different Stages.

Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson speaks with a mixture of glee and relief as he described the arduous task of compiling and selecting live recordings for the band's 1998 three-CD release, Different Stages.

"There were literally hundreds of adat tapes, piled a mile high." Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson, his voice a mixture of glee and relief, is describing the arduous task of compiling and selecting tracks for the band's latest opus, the three CD live release Different Stages. "We ran two sets of eight ADATs a night, so that's 128 tracks. Our engineer had to go through boxes and boxes of tapes in order to determine which were the best nights, and then we all came in to narrow it down to the absolute best stuff. It was a huge undertaking."

The band's fourth live album (following 1976's All the World's a Stage, 1981's Exit...Stage Left and 1989's A Show of Hands), Different Stages features two discs of music recorded during Rush's 1994 Counterparts and 1997's Test for Echo tours, and includes, as a bonus, a third live disc culled from deep in the band's archives; this disc features the lion's share of the band's 1978 appearance at London's famed Hammersmith Odeon.

The 37-song package spans the band's entire 25-year career, and includes such classic hits as "Limelight," "Closer to the Heart," "The Spirit of Radio," "Tom Sawyer" and "Freewill," as well as more recent material such as "Roll the Bones" and "Stick It Out." Also included is the band's first-ever live offering of the ambitious "2112."

"When we started this project, we planned on using songs from lots of different shows and different cities," says bassist Geddy Lee. "Between the two tours, we recorded about 90 shows. In the end, we realized that there were a small handful of shows that just sound better than the rest, in terms of audio quality. The difference was usually due to the sound of the venue itself, which is surprising, considering how controlled our recording process was."

As a recording, Different Stages is clearly state-of-the-art-very full, very fat, very live.

"Yeah, it does sound really good!" says Lifeson. "All the clarity is there, there's really good separation between the instruments and the whole thing has a lot of punch and power. The bottom end is so sweet-it's big, round and deep. And I think the performances are there, too. I feel this record accurately represents what we sound like live."

GUITAR WORLD: Rush recorded three live albums prior to Different Stages. What made you record another one?

GEDDY LEE: Each live record functions as a sort of historical document. I think our sound changes quite a bit over every three- or four-album period, so it's interesting to hear how the band and certain songs evolve. Some fans may say, "'Closer to the Heart' again?!," but, to me, this is simply the best live version we've ever recorded. That justified "Closer to the Heart" being on this record.

So the general criteria was that either it was a song that had never appeared on a live album, and we were very happy with the performance, or it was one of our "classic" tunes that positively smoked, like the version of "YYZ" on this record.

GW: With an undertaking this massive, how does the band keep all of its material in perspective?

LEE: We didn't listen back to every show; that would've been insane. Robert Scovill, our sound engineer, undertook the first level of the process of elimination at his home studio in Arizona. The first step was to weed out all of the recordings with technical glitches, and there were a lot of technical glitches. That immediately narrowed it down to about 12 clean versions of each song, and we'd listen to all of those on a microscopic level. Of the 12, we might find that, on some, the snare would sound a little weird, or the guitar was a little out of tune, or the singer was a little out of tune! [laughs] Eventually, each song got boiled down to the best couple of versions, and from there we'd go with whichever one had the best vibe.

ALEX LIFESON: Some of the tunes that are sequenced together were actually recorded seven years apart. But I think we were successful 'in mixing the songs so that they all run together smoothly.

LEE: We wanted it to sound like one.really great show, even though, in actual fact, some of the record represents the furthest thing from that actual occurrence.

GW: Did the multitracks get bounced to a ha.d disc for digital editing and mixing?

LEE: We originally tried to keep the recording entirely in the digital domain. Our engineer, Paul Northfield, however, wasn't pleased with the results; he thought the tracks sounded too brittle. So we went back to an analog Neve [mixer] for some tube-induced warmth, and actually bounced some of the tracks to two-inch analog tape for that "saturated" analog sound. The two-inch ran in tandem with the original ADATs when we did the mixdown. This ended up giving Paul a lot of flexibility; he could run digital, analog or both.

LIFESON: It turned out to be the best of both worlds, even though it was a long, complicated process. But I feel that we ended up with the desired result.

LEE: And then, when we mixed it down, we mixed to both analog and digital. In the end, for about 80 percent of the album, we used the analog mixdown, or analog "masters." For whatever reason, the other 20 percent sounded better as digital. This created some unusual problems in the mastering process for Bob Ludwig at Gateway. He was drowning in tapes at one point, and he called me, crying, "What am I doing?!" [laughs] I had to talk him through it all.

GW: The performances on this album sound very relaxed and in-the-pocket.

LIFESON: On the last tour we chartered a plane for the first time in 25 years-we didn't bounce around in a bus for eight months. It made a really big difference in how we felt physically. It was so much easier on our bodies, so it was easier on our minds. We weren't exhausted all of the time. I felt better, had more energy and felt happier in general.

LEE: I agree with that. It made a huge difference in how we felt. And we got to play tons of golf.

LIFESON: Yeah. We played so many great courses: Arrowhead, in Denver, which is amazing; it's like you're playing golf in Jurassic Park. And Olympic and Turnberry in Scotland, and Belrieve in St. Louis, and Baltusrol...

LEE: You know, only all the best courses in the world!

Another reason for the "relaxed" sound of these recordings is the fact that we're using in-ear monitors now. I equate it with the vibe you have in the dressing room, where you're playing out of a small amp at a very low volume, and it's so easy to play. It used to be that when we hit the stage, we'd tense up for the "big rock show," and that tenseness came out in the music. With the in-ear monitors, you can create your own custom-made mix that sounds great, thus making it much easier to play; it eliminates a lot of the chaos. I think we're playing much better because the environment is much more controllable. And, of course, the in-ear monitors help tremendously with singing. It's like night and day. I can concentrate a lot more on phrasing and the quality of the performance, instead of just fighting to be in tune!

LIFESON: These in-ear monitors afford you such a great mix, which enables you to play a lot better, night after night. It shows in the fact that there are much greater dynamics in our playing now. You don't pluck the strings quite as hard, or hit the skins as hard, or play muddy, sloppy arpeggios because you can't quite hear the guitar well enough. You can be delicate when you need to be, and play with more overall precision. Then you can relax, hold back, and really lean into the heavy parts when you want to.

GW: I think the "heaviness" we hear in some of our favorite rock music is actually a function of how relaxed and in-the-groove the band is, as opposed to someone beating the crap out of his instrument.

LEE: As with all the millions of bands that have been trying to mimic Led Zeppelin over the last 20 years, they want to sound really heavy and really tough, but end up overdoing it. If you go back and listen to some of those early Zeppelin records, the guitar sounds are kind of dinky! But they're played late on the beat, and there's a particular attitude and a particular sound, and that's what makes it heavy. As we've gotten older, I think we, as a band, have gotten a better handle on laying into the groove.

LIFESON: In all seriousness, playing music is a lot like playing golf-as soon as you relax, everything just happens. It's about getting in the "zone," recognizing it and learning how to get in there without too much effort.

GW: Can you demonstrate how to perform some of your classic songs? How about "Closer to the Heart"?

LIFESON: I begin by arpeggiating this chord [Amaj9], and I use this figure for the intro section [FIGURE 1]. The secret to making this part sound right is to let each note ring as long as possible.

GW: A classic Rush tune that's never been transcribed is "The Trees," which is included on Different Stages. That sounds like a really fun song to play.

LIFESON: Oh yeah, it is. I fingerpick a nylon-string acoustic for the beginning of the tune, over which Ged plays a melodic bass figure [FIGURE 2].

LEE: This part is somewhat improvised; we never play exactly the same thing in this section of the tune. Later on, I play the barnyard animal sounds, triggered from the keyboard. After that, we get into a section in 5/4 time. The whole idea there is to get into a groove that really swings, so that it doesn't feel like an odd time signature.

GW: On the intro to "Freewill," you and Geddy play the same figure octaves apart, correct?

LIFESON: Yes, that's right. The tune begins with this melodic figure based on the F Lydian mode [F G A B C D E: see FIGURE 3A], which Ged and I play the same way as the time signature changes from bar to bar.

At the pre-chorus, I play a series of arpeggiated chords down at the first few frets of the neck [FIGURE 3B]. Like many of my guitar parts, I never play exactly the same thing twice; I like to play around with the arpeggios and create different sounds and different sequences.

GW: "Tom Sawyer" features some tricky arpeggio stuff during the pre-chorus. How do you play that part?

LIFESON: Like this [FIGURE 4A]. I keep my pinkie fretted on the B note, 3rd string/4th fret, the entire time, while the index finger walks around, fretting different notes on the low E and A strings. The fun thing about playing arpeggios like this is that you get a simulated "double-guitar" thing happening.

LEE: For my bass part, I like to reinforce the root movement of all the chords, while throwing in some additional licks here and there.

GW: Alex, the chord voicings you play during the verse section are a bit of a mystery, too.

LIFESON: Some of those voicings are a little hard to pick out. This is what I play [FIGURE 4B]. Like most of my guitar parts, this one has evolved somewhat over the years from what I did on the original studio album.

LEE: Even by the time we finish the first tour after releasing a new record, the parts have already changed.

LIFESON: And we seldom go back to the original record to relearn exactly what we played. We get into rehearsals, wade through it clumsily for the first few takes, and then it all comes back to us.

LEE: And our memories are probably just an impression of what we were playing by the end of the last tour. It's got to have the spirit of the original part, and sometimes the new part is better. A lot of times you end up tweaking and improving a part as you perform it so many times in concert, and that's one of my favorite things about the songs on this live record-they're in some ways better than they were originally.

GW: One of Rush's most powerful and well-loved tunes is "Limelight." How do you play the intro?

LIFESON: I begin with this single-note figure, after which Ged enters and we play the next bit: in unison [FIGURE 5A]. The verse section has some intricate arpeggio work in it, too [FIGURE 5B]. The first chord [Badd4] is based on a conventional 7th-position B barre chord, except I don't barre all the strings with my index finger; I only use it to fret the low B (6th string/7th fret). This allows the top two open strings to ring, which really broadens the sound of just one guitar.

LEE: Because of the trio line-up, we all feel that we need to find subtle ways to fill out the sound of the music, and that's how our playing styles developed. And that wouldn't have happened if we hadn't been a live touring act for so long. When you're onstage night after night you discover the holes and gaps so you invent chord voicings and inversions that work well between the guitar and bass parts

LIFESON: For a rock guitarist, I play a lot of 1st position stuff and use a lot of arpeggios to create a fuller guitar presence.

GW: Alex, how do you play the fast intro riff to "The Spirit of Radio"?

LIFESON: I play it down in the 2nd position, like this [FIGURE 6A]. I keep the D note, 2nd string/3rd fret, fretted the entire time with my middle finger while I play a series of pull-offs on the high E string. I fret the high A note with my pinkie and the G# with my ring finger.

LEE: After Neil [Peart, drums] and I play those syncopated licks behind Alex's repeated lick, we all move into the next bit, which is played at a different tempo [FIGURE 6B].

GW: Do you guys use some "drop D" tunings on Different Stages?

LIFESON: For "Stick It Out" both Ged and I have the low E tuned down to D. For "Driven" Ged uses "drop D" but I use standard tuning and an octave pedal to get all those low D notes

LEE: All of that stuff at the beginning of "Driven" was originally three tracks of bass. Live, Alex uses the octave box to recreate some of those bass parts.

GW: Alex, what was your live setup for these shows?

LIFESON: For recording the guitar, we used what we call "dog houses": there are two 2x12 GK cabinets in there, fitted with G12 Celestions, which are close-miked. These dog houses are closed boxes that house the amps for acoustical isolation. They're lead-lined and weigh a ton. In the beginning, we miked them with Shure SM-57s, but we switched to Audio Technica condenser mics; they gave us a little more fidelity.