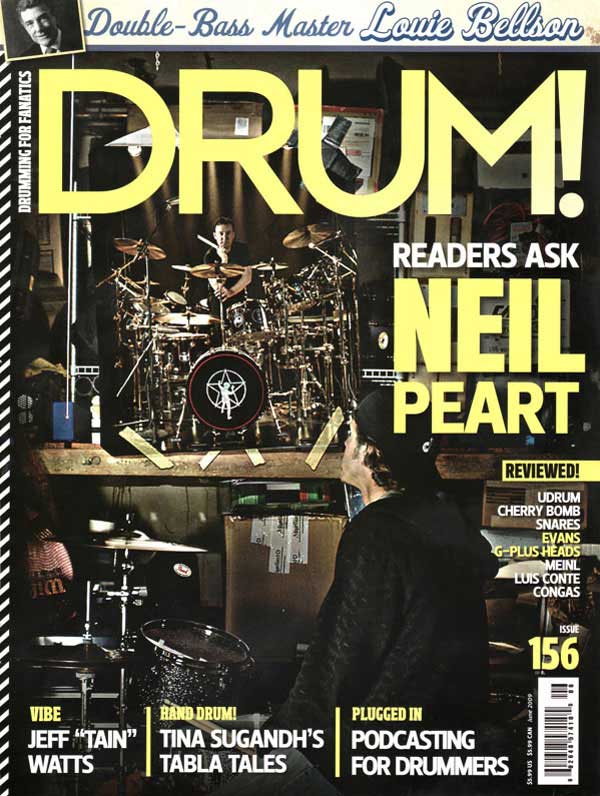

Thus Spoke Neil

DRUM! Readers Interview Neil Peart

By Jerome Brunet, DRUM!, June 2009

When we decided to put Neil Peart on the cover to help celebrate Retrospective III, Rush's new best-of box set, we got the bright idea to let DRUM! readers interview "The Professor" themselves. So we asked you guys to submit questions by email, then we sat back and waited. A gazillion emails later, we realized there was simply no way to print every single question that was posed without publishing an issue as thick as a floor tom. Instead, we had Peart choose the questions that best captured where his head is at - rhythmically speaking. What amazed us was how incredibly varied, original, and specific the questions were - the kind that could only come from diehard Rush fans. So what pearls of wisdom does the world's greatest prog-rock drummer dispense after 33 years on the job? Read on to find out.

What is your favorite live solo?

Michael S. Conley

Sugar Hill, Georgia

Rush fan since 1982

By far my favorite recorded solo is "De Slagwerker," from Snakes And Arrows Live, which is, of course, the most recent one.

It's strange, but people often seem to expect me to cite something from the past as my favorite solo, song, or album - perhaps to mirror their own opinion. While such people are certainly entitled to their preferences and prejudices, I always think it would be a terrible shame if I preferred my work from, say, ten years ago to what I'm doing now. I hope I stop before that day ever comes.

All of those old recorded songs and solos represent the best I could do at the time, but I continue to learn, gain understanding, and work hard on getting better. If you're not getting better, what are you doing?

I have read a number of interviews where you mention that when you get new cymbals you don't use them on stage. You have your drum tech put them on your practice set until they are "broken in." I'm not sure I have ever really understood this.

Jeff Kolln

Yelm, Washington,

Rush fan since 1974

Believe me, when I was starting out, nothing would have made me happier than having new cymbals to play, especially when I was living with a broken one, vainly drilling holes to stop the spreading crack while saving up for a new one.

I have known drummers who refused to clean their cymbals because they believed the dirt warmed up the sound. Well ... perhaps. But really, aging has a similar effect. I have long felt that a much-played cymbal changes in many ways from a bright new one. For example, over time a ride cymbal develops a subtle array of overtones across the bow that lends it a more complex attack, and the bell becomes warmer and more musical. With crash cymbals, the difference is more immediate, and greater: after two or three shows, the attack, swell, and decay become more unified, and even the physical movement of a struck cymbal becomes more responsive - it starts to "dance," I always say.

The metallurgists and alchemists in the cymbal-making business confirm that my feelings are true. Once a cymbal has been played for a while, and the metal has flexed and vibrated, it truly does loosen up, even at the molecular level.

On the higher, musical level their physical and sonic responses are likewise looser, more resilient, and more responsive. Thus, not only do I like to break in new crash cymbals on my practice kit, but because the 16" crash in front of me is so critical, if it should happen to crack, my drum tech, Lorne Wheaton, will move the aged one from my left side over to the right, and put the newer one on the less-important side.

How often do you practice and for how long? Is it simply just the "warm up" as we've seen on [the DVD] A Work In Progress, or do you warm up and then move on to something else?

Kalman J. Kopcsandy

Oreland, Pennsylvania

Rush fan since 1979

I have never been good at following a strict lesson plan: "Play Exercise One ten times, then proceed to Exercise Two." For me, it is much more enjoyable to combine those exercises into some kind of flow, in whatever order and duration seems good to me at the time. And yes, for me, the "warm up" is the same as practicing.

As I have demonstrated on instructional DVDs, I like to have a long, loosely structured session that engages some of my current interests - like overlaying time signatures or developing certain stickings - and make that into a free-form exploration, wandering from one motif to another. Thus every practice session is different, sometimes dramatically so, but every one will include similar elements because those are the things I think I need to work on or enjoy working on.

Last year, when I was studying big band drumming with Peter Erskine, the approach to practicing was somewhat different - mainly because Peter restricted me to playing hi-hat only, and inspired me to attempt a completely different ride stroke.

But even playing nothing but hi-hat every day for a couple of months, the practicing never became tedious. While I played that hi-hat every day, to slow and fast metronome settings, I experimented, learned, and developed all the time, even when I wasn't aware of it.

I once read an interview with an Indian tabla player who said that while he practiced every day, only once in every ten days or so did he feel he'd really "moved ahead." I understand about that, and it's important information: If some days it feels like you're only going through the motions, don't worry, because those motions will still add up to an ever-growing facility and understanding that will one day blossom into something new, as if by magic. You'll think, "Now where did that come from?"

But it isn't magic. It's hard work.

As diverse of a drummer as you have become, are there still techniques other drummers employ that continue to elude your abilities? Or can you master anything you've heard or seen within ten minutes of attempting it yourself?

David Gostin

New Woodstock, New York

Rush fan since 1984

I wish! One thing that makes us all human is that we each have different gifts, and different handicaps. There are plenty of things I will never be able to do - in ten minutes or ten years!

On the other hand, you've got to be careful about surrendering too easily to your assumed limitations. I have talked before about that determination in regard to playing in odd times, and a good example was the 3/4 exercise, like [Max Roach's famous solo] "The Drum Also Waltzes." When I first tried that, laying down the bass drum and hi-hat ostinato, I couldn't seem to play anything over it. I thought to myself, "I can't do this." But I persevered, day after day, and pretty soon, I was surprising myself. And from then on, until today, it remains one of my favorite musical vehicles.

Similarly, at the time of making the Anatomy Of A Drum Solo DVD, I came right out and said that I considered myself more of a compositional soloist than an improvisational soloist. Right after saying that I decided, "Hey, wait a minute - I want to be more of an improvisational soloist!" So before the next tour, Snakes And Arrows, I set out to force myself to approach my solo with that attitude: to combine composition and improvisation in a way that would give me both freshness and consistency. Every time I played "De Slagwerker" on Snakes And Arrows Live, I dared myself to make the solo less arranged and more improvised. Thus it continued to change and develop through more than a hundred shows, based on the same overall structure, but never even close to the same twice.

So I guess the lesson there is that you do have to learn to accept your limitations, but don't accept them too easily.

After watching Rush's latest video, Snakes And Arrows Live, I've become aware more than ever of your use of electronic triggering on stage. Do you ever feel like a slave to the technology?

Mike Douglas

Dallas, Texas

Rush fan since 1982

The truth is actually quite the opposite, Mike. I used to feel like a "slave to the technology" in the olden days because I would have to find a place to put those gigantic instruments where I could still reach them, then figure out how to change mallets in the middle of a song, for example, to play those various chimes, bells, and blocks.

It was a nightmare of choreography, not to mention mike placement and mixing. And in fact, I would often have to miss certain notes, just to make those stick and mallet changes in time.

These days, with the pads, foot triggers, and MIDI-marimba, I can just hit or step on a trigger, and the required sound is there, loud and clear. For those "effects" purposes, electronic triggers are much more flexible and useful than all that junk used to be.

Of course, they are no replacement for acoustic instruments. A real, trained percussionist - as opposed to an over-reaching drum set player - is never going to be happy with samples of timpani or chimes. Likewise, I have never given up a single one of my acoustic drums, because they have subtleties that I don't believe electronic drums will ever replicate. But when it comes to simply producing a sound, triggers and samples are a wonderful tool.

During the Grace Under Pressure tour, back in 1984, I heard you say on a radio interview that "'Tom Sawyer' will always be the hardest song for me to play." Twenty-five years later, is it still the hardest song for you to play?

Gary Boothe

Keller, Texas

Rush fan since 1976

Yes, there's no making that song easier to play - it still takes everything I've got. To get the right sound and feel, a drum part like "Tom Sawyer" requires full-force, blunt-object pounding with hands and feet, but there's also a demanding level of technique, smoothness, and concentration.

Playing "Tom Sawyer" properly - or as close as I can get on a given night - requires full mental, technical, and physical commitment, and I can't imagine there would be any way to make that kind of output easier. And if you ask me, it shouldn't be. If it wasn't hard, it wouldn't be satisfying to get it right!

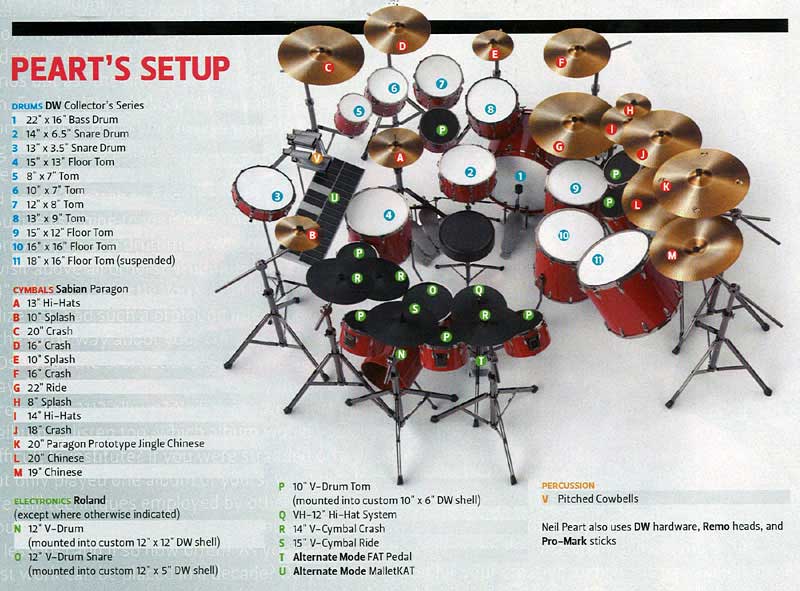

You're known for changing your drum kit prior to each album and tour. Have you ever made the attempt to go back to a much earlier setup just to see what might be the result in your playing style?

Ed Dobbins

Baltimore, Maryland

Rush fan since 1980

When I review my setup before starting work on a new album, I consider everything. However, going backward is not an option. For example, I can't imagine ever moving my ride cymbal back over to my far right, where I used to put it. That was only done to accommodate another tom in front of me, and since then I've found other good places for toms, sometimes creating much more interesting possibilities, like having a small floor tom on my far left. Most importantly, I would never compromise what I have come to learn is the essential relationship between snare and ride.

Similarly, I started out using two bass drums, but once double pedals became reliable and responsive, I was more than happy to dump that second bass drum - more room for everything else.

I have actually heard some people lament that change in my setup because they think two bass drums looks cooler. Well, I sure like my drums to look good, all right, but not at the expense of, you know, playing the instrument.

What do you do with drum kits you used during past tours?

Mike fisher

St. Johns, Newfoundland

and Labrador, Canada

Rush fan since 1977

For now, I have hung onto the R30 kit, which is presently in the Motorcyclist Hall Of Fame museum near Columbus, Ohio, on display with my motorcycle from the Ghost Rider book. I still have the Snakes And Arrows kit of course, and a couple of other more recent ones, which I will likely donate to a worthy recipient, like a school music program, where all the rest of my excess equipment has gone in recent years.

My question is in regards to your rationale behind lowering your throne height over the last five years. Have you noticed greater ease playing, or any accompanying back problems commonly associated with a lower throne height?

Jason Jecman

Lisle, Illinois

Rush fan since 1978

In fact, I have never lowered my throne, just raised the drums around it. That began when I studied with Freddie Gruber in the '90s. His teaching was largely about one's physical approach to the drum set, and the major hardware change I made at that time was moving my throne back, to give a more natural physical approach to bass drum and cymbals.

I also raised my snare drum - a lot - so that its striking surface was at navel height, the center of gravity for the male body.

All of that has definitely worked for me, ergonomically, particularly in the all-important factor of avoiding injury. All motions of hands and feet, arms and legs, are now natural, and my back is arched evenly over the drums, without pain or strain.

Why is the second solo missing from "Natural Science" when played live?

Will Holt

Hampton, Virginia

Rush fan since 1981

In deciding to bring that song back into our live set a few years ago, after not playing it for a while, we made some arrangement changes that we probably would have done at the time it was recorded in 1979 if that long, complex, multi-part suite hadn't been written and recorded in about two days!

In most cases, we are happy to play our songs as they were recorded because we remain contented enough with them that way, but other times we can't resist reconsidering.

We have done that with a few other older songs, where we felt it simply would have been better without a certain part, or as with "Entre Nous" last tour, where it would have been better to repeat a certain passage.

Had you been given the chance to meet Buddy Rich or Gene Krupa, what would you have talked with them about?

Douglas Whelan

Puyallup, Washington

Rush fan since 1983

I would probably have talked with Buddy about fast cars. Buddy drove a succession of Jaguars, Ferraris, and Porsches with the same intensity he brought to his drumming.

With Gene, I would have asked about Dave Tough - to me, somehow the most intriguing of the old-time drummers, and a contemporary and fellow Chicagoan of Gene's. Dave Tough was a frustrated poet, though he did publish one book, which I would love to find. He was beloved by other drummers, and the musicians he accompanied with consummate musicality and taste, but he felt drumming was beneath his higher calling. Those conflicts activated the demons that destroyed his career and, by age 40, laid him low.

If you judge a person by how much he was loved, though, then Dave Tough was a truly gifted man. But like some other gifted-but-conflicted drummers, like Dennis Wilson and Keith Moon, perhaps he just didn't know how much he was loved or felt unworthy of it. Sad, but it happens.

Pro To Pro

Jason Bittner Throws His Hat Into The Ring

When I saw the Test For Echo tour multiple times, there was a point on one leg where I saw you playing with an elbow brace on. What exactly was going on at that time? How did you overcome the injury while still managing to kick serious butt for more than three hours a night?

Thanks Jason, and that's a good question because its answer gets into so much worthwhile territory.

Short version: Late in that tour I was suffering from tendonitis in my right elbow, as a result of too many long shows, and maybe too many long motorcycle rides. Because the rider's right hand is locked on the throttle most of the time, some doctors I consulted during the tour tried to blame my condition on the motorcycling rather than the drumming, but they were proven wrong, as we'll come to shortly.

Tendonitis is caused by tendons becoming inflamed, then the swollen tissue abrades against its channel through the bones, causing more inflammation. Thus, the worse it gets, the worse it makes itself. The only cure for tendonitis is rest, but I wasn't going to be getting much rest in the middle of a tour, so I tried various braces and bandages. They helped a little but it remained very painful. However, the one thing I was grateful for was that it didn't affect my performance. I could play through the pain, which wasn't very nice of course, but at least I didn't have to live with the feeling that my drumming was being compromised. That would be awful.

After the tour, it took a few months of rest for the internal inflammation to subside, but it eventually did, and I am glad to report that it has never recurred. I think the reason is simply that on subsequent tours, we had a less-punishing schedule, with fewer shows in a row, thus more recovery time between them.

On the R30 tour, for example, our shows were the longest yet, with plenty of long motorcycle rides between them, and the Snakes And Arrows shows were no picnic either, but I haven't suffered from any other chronic conditions, I'm glad to say.

Just general aches and pains all over while I'm on tour, and they go away after a few weeks.