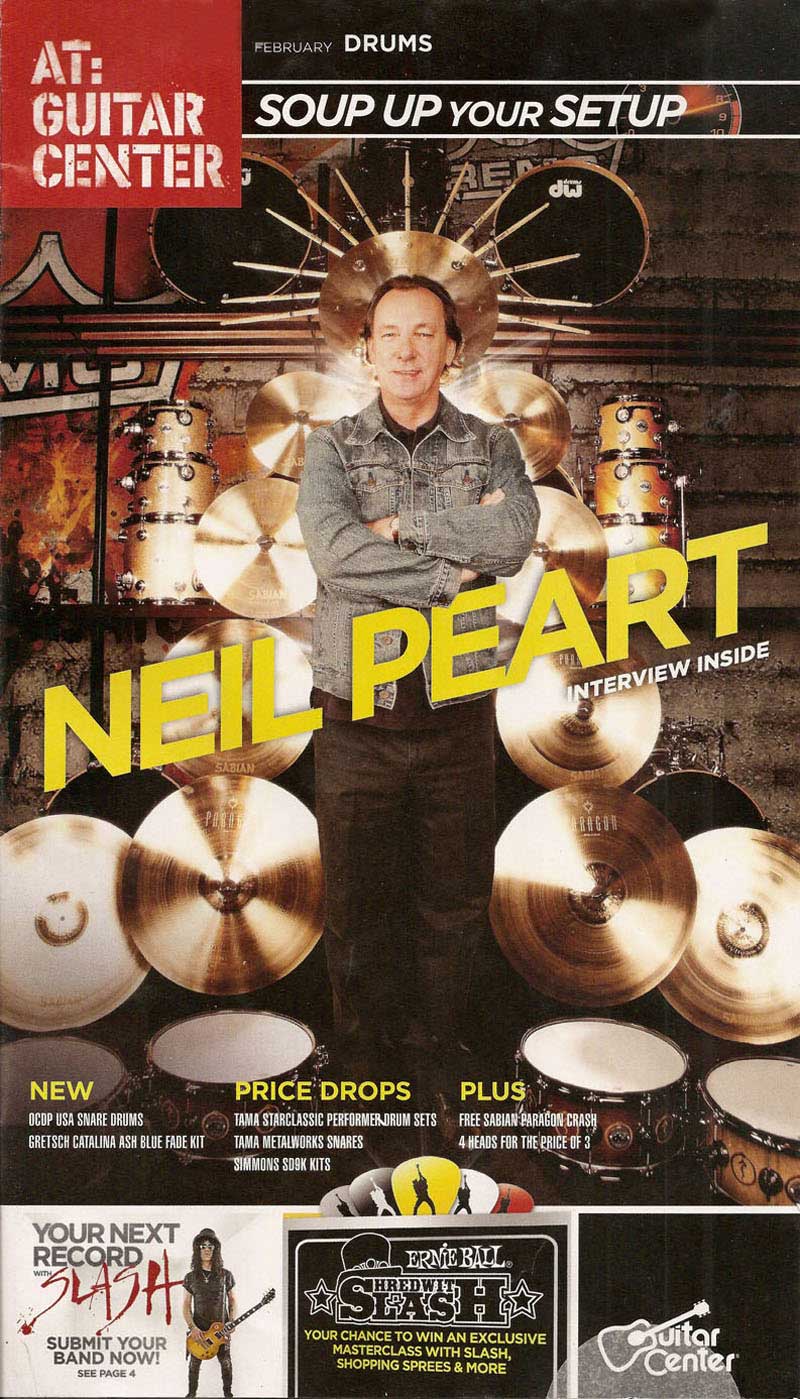

Neil Peart Interview

At Guitar Center, February 2010, transcribed by pwrwindows

Attention all drummers, legendary Rush skinsman Neil Peart has a crucial piece of advice for you, and it's probably not what you're expecting: the singer in your band is quite often the best indicator of tempo.

"When I'm playing live, if I'm worried that it's a little bit too fast or slow, I listen to the singer to see if the phrasing is falling comfortably," says Peart. "I'm telling every drummer this - Every singer wishes that you would listen to the phrasing to decide on the tempo."

In fact, in our in-depth conversation with the master of progressive rock drumming, we were fortunate to learn quite a bit about the way Peart operates. From technique to touring, inspirations to custom gear, Peart's life as the driving rhythmic force behind rock heavyweights Rush has brought him wisdom and insight that could span several lifetimes.

Originally hailing from Ontario, Canada, the famed drummer once worked with his father, selling farm equipment. Always the innovator, he created his own drum riser from shelving. In fact, some of the same design elements are still incorporated into his riser today.

Rush started out opening for artists like KISS, Aerosmith, Blue Oyster Cult and Ted Nugent. By their fourth album, 1976's 2112, the band was headlining small halls, eventually working their way into arenas and on to American commercial radio. By the early '80s, Rush had become a household name with hit singles like "Tom Sawyer" and "Limelight." Peart was quickly recognized as one of the era's most important drummers, a reputation only augmented by his forward-thinking embrace of new techniques and technologies, including the addition of electronic drums to his sizable acoustic kit.

Peart is also Rush's primary lyricist and sees his knowledge of the songs' vocals as essential.

"Some bands record a song before the lyrics are written and that would just drive me crazy," he says. "It forces the drummer to play so simply, to avoid being in the way of the vocals. I like to know where the vocals are going to fall so I can play responsibly to them, if there is a place where I know Geddy's (Lee, Bassist/Vocalist) going to be accentuating syllables, I like to be there too, if it seems appropriate, and to know where I can make noise between lines instead of where the vocals would be. That's a huge advantage and gives me so much more freedom. I don't ever have to worry about wandering over things and I can be so much more supportive as a drummer behind the vocal rhythms, never mind the lyrics. Beside the fact that I wrote them, as a drummer I'm in there knowing them and I know what the passage is supposed to express in the deepest way."

While Peart holds the reins lyrically, the band collaborates quite heavily on the music, including the drum parts.

"I write lyrics in a quiet room somewhere else, so the two of them work to a drum machine," Peart says. "Alex [Lifeson, Guitarist] is also a very intuitive drum programmer, so he'll put together something. Sometimes it's only the tempo, but other times he'll strike a rhythm. A song of ours, 'Mystic Rhythms,' is based around a drum pattern he came up with. We call him the musical scientist - there are bits and pieces of songs where he's come up with some bizarre guitar-player drum pattern and I'll build on that because I like it. But basically I get a demo with a drum machine and one without the drum machine, just a quick track for me to play to."

Still a devoted drumming student, just last year, Peart took lessons from renowned jazz drummer Peter Erskine to expand his percussive palette with daily practices, focusing on the hi-hat and metronome. In fact, it was Erskine who encouraged Peart to loosen up his hi-hat technique.

"I like very clean definition riding on the hat or control over its amount of openness. I always found I got that with a very tightly bolted-down top cymbal. But lately I've been playing with it loose, so it'll be interesting. Maybe I won't be able to play older songs that way? I don't know yet, but I think it'll be fine and it's definitely given me an interesting new way to do things."

Though he admits to not having a kit setup at his home, Peart makes it a point to practice, driving up the coast from his Los Angeles home to the Drum Workshop headquarters in Oxnard, California, for a round of wood shedding. And unlike some musicians, he doesn't mind rehearsals.

"I'm a really good rehearser," he says. "Geddy makes a joke that I'm the only guy he knows who rehearses to rehearse, because before the band starts rehearsing I rehearse for two weeks on my own, you know, just to be ready to rehearse, to have my own parts of the songs ready for the other guys."

Peart's drums are an integral component of his performance. His kits are envied and coveted by gear-obsessed drummers, who follow every change and addition to his setup. One of the most recent innovations was the incorporation of a 23-inch bass drum, an odd size both literally and figuratively.

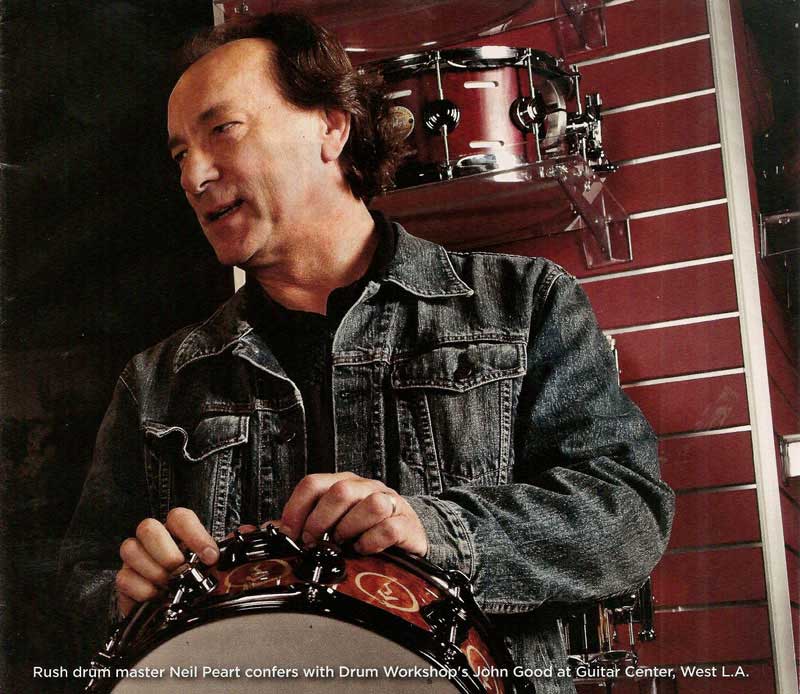

"I've always liked the way 24-inch bass drums sound out front, but I never liked playing them 'cause I use a 22-inch and the 24-inch was just that much floppier," he notes. "So, I was telling this story to John [Good of Drum Workshop]. He says, 'How about a 23?' Well, there's never been a 23-inch bass drum, but there was at that moment in his mind. So, he built it and it worked and that's the bass drum I use all the time now."

Another recent addition to Peart's setup is the Drum Workshop VLT snare, which he praises for its versatility. A serious accolade coming from a drummer who used to travel with roughly a dozen different snares.

"I still went through the motions, of course, of comparing the other ones for specific songs and found the VLT would always do the job. The quality of the bearing edges is so perfect. I was showing it to my dad. Again, someone not a specialist in the drumming world, but I was showing him a raw wood shell. Just feel the bearing edge there and the bevel of the angle, how perfectly milled that is. Imagine a membrane stretched over that, how much better it's going to resonate because of that beautiful surface. In the old days they didn't have that. They were pressing some plywood together and that leaves a pretty chunky bearing edge. It's Drum Workshop's precision and care that have improved on that."

Peart has also been heavily involved in the design of his Paragon line of Sabian cymbals. Working closely with Mark Love, the company's alchemist and cymbal guru, Peart played every version of the cymbals during their development, providing detailed feedback to achieve his desired character and tone.

"I use a lot of the bell on the ride cymbal for syncopated patterns and I have a very specific idea of how I want it to be," he says. "We spent a lot of time just on that little area of the ride cymbal, every variation possible on the bell to get it musical, while retaining the percussive definition that I was after. The roundness of that little sound is so critical and was worked on so critically. Even on the 20-inch crash cymbal the bell has that same musicality because of the integrity of the design of it all."

With over three decades of professional experience, Peart has seen the recording industry evolve from format to format. But what does he think about the changes in the music industry, particularly in the various modes of delivering music to the masses?

"I know that the mechanism that brought us up doesn't exist anymore," he says. "For instance, a perfect example of how reversed it is, in those days we made no money touring for a long time, even into the successful years. You counted on record sales and songwriting to make your living. And touring was a way to publicize that. Suddenly, in the last 10, 15 years all that turned around and our income is entirely from touring, and recording is an indulgence. In a band like Rush, no one's going to pay us to make a record. It's going to be an indulgence. Even Snakes and Arrows basically paid for itself and that's it, and if we want to make a living beyond that we have to go on the road and tour."

True to revolutionary form, Peart has even put his own spin on touring, taking it to a higher level of purpose. Instead of spending countless hours in a tour bus or on an airplane, Peart opts to travel by motorcycling across the country from gig to gig. This unique approach provides Peart with a sense of adventure and allows him to indulge his love of exploring off the beaten path.

"Traveling by motorcycle, I travel on my own. I just happen to have a bus with a trailer in the back," he explains. "Then, after the show I leave straight off the stage, sleep on the bus and unload the bikes in the morning. I've made up routes for the next day - all the back roads, all the small towns. If it's a day off, I can travel four or five hundred miles, stay that night wherever I end up and then ride to the show the next day. For me, in the touring mentality, it's a great escape, total focus on something else. To travel around on the airplane or on a bus day after day, I couldn't. I would go crazy. Whereas now, everyday's an adventure. And people laugh, but when I get the itinerary, I don't look at where we're playing. I look at the days off. 'OK, I've got two days off between Albuquerque and Denver? Yes! Heaven!' Just being able to ramble around that beautiful part of the country."

It's been 35 years since Neil Peart first joined Rush. In that time, the group has risen to iconic status, garnering countless, devoted fans and an impressive list of industry accolades. And while the drummer and lyricist is arguably one of the most highly accomplished players in rock music history, Peart remains a student at heart, always learning, with his eyes fixed on the road ahead.

Soup Up Your Setup

By Neil Peart

Equal parts drummer and philosopher; Neil Peart has always put a lot of thought into his kit. Here he offers some insightful tips for great ways to "Soup Up" and "Shake Up" your setup.

At the beginning of each new Rush project, I stand in front of my drumset in the rehearsal room, and think about what I might change. Certain relations of drums and cymbals are simply necessary to me, fundamental to the way I play, but over the years, I have been able to "shake up my setup" with plenty of creative changes.

Even with the simplest drumset, there's something you can do - reverse the order of toms, for example, as Kenny Aronoff did: putting low ones before high ones, forcing you to play in a different way, or achieve a different sound if you play the same way.

l like to move my crash cymbals to different places when I'm practicing, just to put them in an unusual physical relation and see what results.

Adding even one sound to your setup can help you think differently. An "effects snare" is one example - placing a piccolo or marching snare to your left, say. Or a timbale or two Bongos. Or as Dave Weckl once used to great effect, a djembe.

It was Dave's example that tempted me to add a floor tom to my left side back in the early '90s, and that has continued to give me plenty of variations for different fills, or rhythmic compositions.

Around that same time, I was grateful to discover that DW had perfected the double-pedal, for I was able to eliminate the second bass drum, and free up that space.

In that "footy" category, pedal cowbells, and tambourines are fun.

There are many fun and creative uses for effects cymbals - many variations of China types, or the infinite splash-type cymbals that have appeared in recent years, often with two or more metallic bits sandwiched together, and offering short, sharp sounds that can be combined artfully.

The ultimate add-on in modern times, of course, is electronic drums. In my case, that's the Roland V-Drums. Where in the '70s and '80s, I used to surround myself with a percussion catalog's worth of wood and metal - temple blocks, orchestra chimes, glockenspiel, wind chimes, bell tree, crotales, even timpani and gong, now those sounds are accessible by foot-triggers and pads.

During pre-production and songwriting times, when I'm experimenting with new hardware and setups, l like to have my drum tech, Lorne Wheaton, set the V-Drums to a different patch every day. I sit down to play without knowing what sounds are going to emerge, and see where it takes me.

Whether it's adding a single bongo or an entire orchestra, it's worthwhile shaking up your setup from time to time. You might surprise yourself.