A View From The Middle

Exploration and Discovery In The Middle Grades Curriculum

By David C. Virtue, Middle School Journal, Vol. 42 No. 1, September 2010

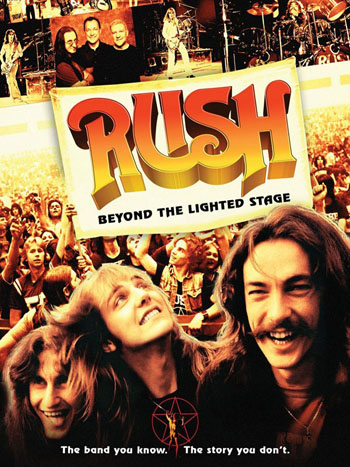

One of the highlights of my summer was seeing the film Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage, a documentary about a Canadian rock trio that happens to be one of my all-time favorite bands. One particular scene captured my interest as a middle grades educator. Early in the film, the camera pans Fisherville Junior High School in North York, Ontario, where two of the band members - Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson - first met.

What struck me about this part of the film was how it portrayed early adolescence as a critical turning point in the lives of these individuals. The lifelong friendship between Lee and Lifeson began, like so many other deep and enduring human relationships, during early adolescence. This was also a time in life when they discovered a love and talent for music - an avocation that eventually became their profession.

Early adolescence is a time of exploration and discovery when young people learn things about themselves, others, and the world that will shape the rest of their lives. This has profound implications for middle grades programs. As Mary Compton and Horace Hawn wrote in Exploration: The Total Curriculum (National Middle School Association, 1996):

The middle school is the right time for students to discover - discover themselves, their abilities, interests, and limitations; discover others and examine the values, mores, and customs of the dominant society as well as those of other societies and cultures; and discover one?s environment and our interdependence with it. (p. 17)

This We Believe: Keys to Educating Young Adolescents calls the middle grades "a finding place" where young adolescents find friendships; personal fulfillment and self-actualization; and academic, vocational, and recreational interests. It is at this intersection of formal schooling and individual identity formation that the very purpose for middle grades education lies.

School systems have embraced exploration and discovery to varying degrees and in a variety of ways. Middle grades schools often require students to take non-core subjects and choose elective courses, and they offer sports, clubs, and other extracurricular activities. Many states are implementing provisions for career exploration in schools, particularly in the middle grades. In South Carolina, for example, the Education and Economic Development Act of 2005 provides for career education beginning in the elementary grades and requires each student to create an Individual Graduation Plan in which he or she specifies a choice of career cluster and an education strategy for achieving a career goal. Many other states have similar programs involving career clusters and graduation plans.

When viewed from the middle, these programs and policy initiatives are encouraging, as they have the potential to open doors to exploration and discovery in middle grades schools. In practice, however, many educators perceive exploration and academic rigor to be mutually exclusive qualities of a middle grades curriculum. Exploration implies broadening the curriculum at a time when testing and content standards policies have continually narrowed the curriculum to focus on very discrete strands of "important" knowledge and skills.

The most powerful engine for exploration and discovery in middle grades schools is neither top-down state policies nor school-wide curriculum frameworks; it is the grassroots efforts of creative, committed middle grades educators who approach exploration as an attitude - a curricular stance - and not as a curricular add-on. The middle grades literature is rich with examples of educators who create curricula and instructional plans that equally embrace exploration and academic rigor. These educators think differently about curriculum, instruction, and assessment. They allow students to play with ideas and pursue answers to such important questions as: What am I good at doing? and What do I enjoy doing? When educators enact these principles across the curriculum, they help to fulfill the vision for developmentally responsive middle grades programs.