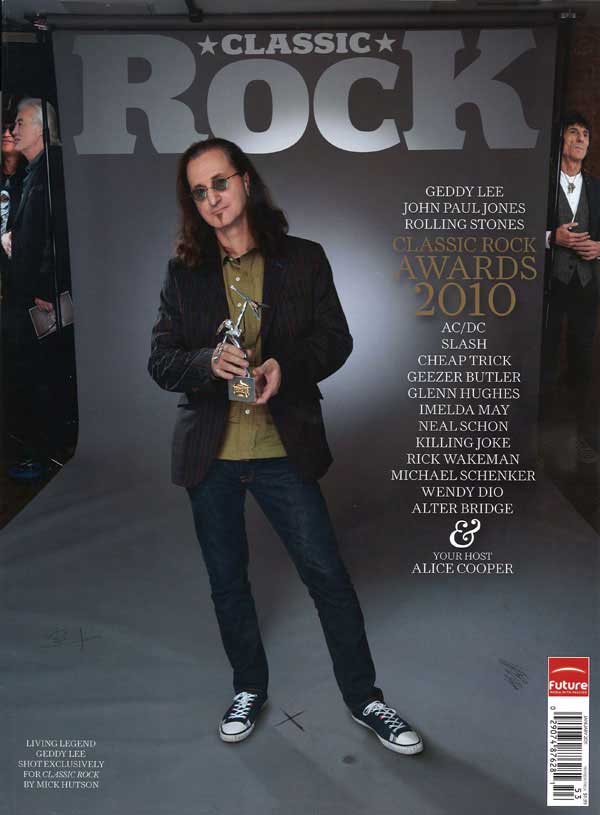

Living Legend Award / Pictures in the Frame

By Jon Hotten, Classic Rock, January 2011, transcribed by John Patuto

Living Legend: Rush

With 24 gold and 14 platinum records, more than 10 UK Top 20 albums, seven Juno awards, six Grammy nominations, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the veteran Canadian trio are deserving recipients.

You've just had your photograph taken alongside Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, Tony Iommi and Geezer Buder. That's quite a line-up shot.

[Smiling broadly:] Three bass players and two guitar players; that means we [the bassists] win!

Do you enjoy events such as this, or are they a bit of a trial?

They can be. They're not really my cup of tea. Talking in front of your peers is a whole different ballpark. And putting myself alongside all these esteemed gentleman that I admire so much [gestures to all the musicians milling about], that seems a bit surreal. John Paul Jones is one of my all-time heroes.

All the previous winners of the Living Legend have been individual performers - Lenuny (2005), Alice Cooper ('06), Jimmy Page ('07), Ozzy Osbourne ('08) and Iggy Pop ('09). This is the first time a band has received it.

Wow, that's quite an accolade.

What does this award mean to you personally?

It's had a pretty big impact on me. Sitting there and watching person after person after person go up and claim their prize, then having to do likewise. It's extremely humbling.

Is there anyone that Rush would like to dedicate it to?

Our fans. Our amazing fans, especially here in the UK. We haven't always been as attentive to them as we should, but I appreciate their loyalty and support.

Rush have been playing new material at their shows in North America. Is the new album nearly finished?

No, it's a long way from finished. About half of it is written, hopefully it'll be done by the end of 2011.

What about gigs?

After we finish the writing, we hope to be in Europe next spring, sometime around May. [Rush recently confirmed a series of UK and Irish dates in 2011, beginning on May 12 in Dublin.]

As a band, do you have any preference whether you play indoor or outdoor shows?

I like both. In May, I think we'll be playing indoors. In the future, though, doing some European festivals is something we would like to do.

Pictures in the Frame

Thirty years ago, Rush released their most successful album to date. Geddy Lee remembers the making of Moving Pictures.

After 30 years, the memories blur. Geddy Lee is thinking back, hard, to the making of Rush's Moving Pictures album. This was August 1980, or possibly September, in a rented house on Stony Lake, Ontario. Maybe they wrote Tom Sawyer first, or perhaps it was The Camera Eye. Either way, it didn't feel like they were doing anything out of the ordinary.

"It's hard to realise that Moving Pictures is so old," the band's bassist and vocalist says evenly. "And at the time, it was just another album in Rush's history. But the years have been very generous to it. This was the point at which we made a real transition musically and lyrically. People might say it was the birth of the modern Rush. I think it was a more gradual process than that, but this album was a very important one for us. We were originally going to do a live album. But then a friend of ours suggested that, as we were changing our style so fast, we should really think about delaying the live album and go into the studio again. We thought about it, and this made sense."

What comes back to him quickest is the atmosphere and the surroundings, first at the house on the lake, and then at Le Studio, in the small town of Morin Heights up in the mountains outside of Quebec, where Rush had already recorded Permanent Waves, and there they would go on making records until 1994.

"What a beautiful setting," Lee says. "We all lived in a house a short walk from the studio and went there through the woods every day. It was very inspirational, because the studio was located by a lake. Some people might wonder how such a tranquil setting could be a good thing when you're making a hard rock album, but it worked for us."

That mood is there, though, in the album, ineffable but present in its background colours. At the turn of a new decade, everything about Rush was becoming more earth-bound, more toned, more subtle. They were no longer kids - Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson were 27, drummer Neil Peart 28. They were no longer the gauche Zeppelinistas that cut Fly By Night and Caress Of Steel either, nor the blazing zealots of 2112, or even the lofty sci-fi geeks of A Farewell To Kings and Hemispheres. A year earlier they had made Permanent Waves, a departure for them in that it mixed up their usual deep prog with a couple of DJ-friendly radio tunes, Spirit Of Radio and Freewill. They'd had a US top-five album as a result. They were changing, but they weren't quite sure into what.

"We had nothing at all written for the album at the time," explains Lee. "It was a case of starting it all from scratch. What we did was hire a house at Stony Lake. We set up our equipment and jammed together from Monday to Friday, and then went home for the weekend. That's how we tended to do things in those days. We'd get it all worked out live, go in and record and then just overdub and replace one or two things. It was only later in the '80s that we got into doing elaborate demos, when Peter Collins produced us. For Moving Pictures we clid actually do some demos, with Terry Brown, who was our producer at the time. We went to Phase One Studios in Toronto. From what I remember, the first songs we worked up were either Tom Sawyer or The Camera Eye. It is 30 years ago, so it's hard to be exact."

The one thin sliver of controversy that had attached itself to the band was to do with their worldview. Neil Peart had based Anthem, the first song on Fly By Night, and 2112, plus others like Freewill and The Trees, on the books of Ayn Rand, a writer who, it's fair to say, polarised opinion - she was either visionary philosopher or amphetamine-addled nutter, depending on where you stood. Rand's macho heroes, The Fountainhead's Howard Roarke or John Galt in Atlas Shrugged, fought manly fights against dystopian societies bent on crushing their virile inclividualism. Rand called it Objectivism, others called it, euphemistically, 'far right', and Peart and Rush were sometimes caught up in the argument. The reality is of course more nuanced. Geddy Lee was one generation removed from a fascist war, his parents Polish Jews who had survived the concentration camps of Dachau and Bergen-Belsen. Orwell's 1984 still lay ahead; the Berlin Wall was still up; monolithic communist super-states comprised the Eastern bloc; the Cold War raged, both sides tooled-up and nuclear and talking tough. Peart wrote against a backdrop of mutual fear and suspicion.

Lee commented in a 2004 interview that Rand had been "at some point in my life a formative influence, but one of many, I would say". By 1980, Rush were less idealistic, and more nuanced, too. 'His mind is not for rent/to any god or government' ran a line in Tom Sawyer, a new song that the band were having trouble nailing down; while another, Red Barchetta, returned to a dystopian future; and a third, Witch Hunt, was part of a song cycle called Fear, that would cross several albums.

"There were lots of moments in the past when I've not felt happy with the lyrics Neil has come up with," says Lee. "It happened more in our early days, and by the time of Moving Pictures it was less prevalent. The way Neil and I work is that he'll how me ideas for a few songs once he's written the lyrics. I'll then go through them and make comments. Sometimes I'm totally happy with what Neil's done. At others, I'll note a few lines I like, and he'll then go away and reconstruct the song. There's a lot of communication between us, and Neil is obviously very aware of how I think. Neil is rare in that for him what matters is doing the work. If his lyrics end up on the album, then fine. If not, he accepts it without argument. As far as I can recall, the only song we didn't end up using on Moving Pictures was one called Sir Gawain And The Green Knight. I can't now remember why it ended up being missed off."

"Tom Sawyer was a collaboration between myself and Pye Dubois, an excellent lyricist who wrote the lyrics for the band Max Webster," Neil Peart has recalled. "His original lyrics were kind of a portrait of a modem day rebel, a free-spirited individualist striding through the world wide-eyed and purposeful. I added the themes of reconciling the boy and man in myself, and the difference between what people are and what others perceive them to be - namely me I guess."

"Whenever I think of Moving Pictures, the first thing that comes to mind is Tom Sawyer," says Lee. "That song has got us everywhere. It's been used in movies, TV shows, so many different places. Strangely, it was the song we worked hardest on in the studio, because it didn't feel at all right. It appeared to be lagging behind the others. Then it ends up being the one that everyone loved. Just goes to prove you're never sure when you finish an album what people will think."

Tom Sawyer, perhaps more than any other song, would be the one that signalled their transition best. Lee's synthesisers construct the growling backdrop for the intro, and later he takes a brief keyboard solo. Rush's sound had become deep and complex, musicianly in the best way. The Tom Sawyer riff is thunderous and unforgettable, while Lifeson's harmonic intro sweetens Red Barchetta. YYZ is that rarity - a listenable instrumental, and Limelight offered proof that the band could do pop rock. In the days of vinyl, it was a perfect side of music. It would be only later on Moving Pictures that Rush would acknowledge their past, with the 11-minute opus The Camera Eye, and then the brooding darkness of Witch Hunt.

"The Camera Eye was the last really epic song we wrote," says Lee. "It's 11 minutes long. At the time, we really didn't appreciate it. Back then we thought it was too long and repetitive. We didn't understand the mood it generated. And it got dropped from our live set very quickly. I think the last time we did it was on the Signals tour. But when we decided to do the whole of Moving Pictures on our recent American tour, Alex and I sat down in the studio and listened back to it. We did feel it was a little overlong, so managed to snip out about a minute. Then we had to learn the new version.

"Witch Hunt is part of a cycle of songs called Fear," Lee continues. "That was Neil's idea. It's actually the third part first. This one deals with the effect fear can have on a crowd or a mob. From what I can remember, Neil had the idea at the time for a cycle of songs like this, even though Witch Hunt was the only one written. We did one on Signals [The Weapon], another on Grace Under Pressure [The Enemy Within] and finally one on Vapor Trails [Freeze]."

The record was completed a few days late. "During the mixing stage, things started to go wrong," says Lee. "We were getting stuff happening that wasn't supposed to be there. Terry Brown told us that the only thing we could do was shut the thing down, and get someone to fly over from England to fix it. Without getting too technical, the problem was traced to a faulty wire, and there was too much moisture in the earth, and it was giving us spikes in the mix.

"In one way that was a good thing, because we did some of the mix in the old-fashioned way, manually. There were four pairs of hands on the desk, trying to get things done, because all of the band were actively involved in all of the production, and it made it a lot more exciting for all of us. Using a computer was a little more distant. We loved getting our hands dirty." The triple-punning album sleeve was also a departure for a band fond of portentous symbols on their covers.

"We always had the album title in our minds," says Lee. "We wanted the whole vibe to be very cinematic. That was the concept. To have the music also telling the story of the lyrics, if you get what I mean. I'm sure it was Neil who came up with the title, and he certainly had a major input into the album sleeve. He showed Hugh Syme, who designed it, some early lyrics, so he'd get the feel for where we were coming from. Then Hugh came up with some ideas and showed these to Neil. When the two of them were happy, they brought it to Alex and me, so we also had a say.

"I like the triple play on the sleeve with the words moving pictures," Lee explains. "You've got the pictures literally being moved out of the building, then the old couple who were moved to tears because they'd dropped their shopping bag, and finally the film crew on the back cover, making a moving picture. Again, it's all to do with our sense of humour. We were very aware that it was really time to get away from the fantasy and science fiction elements that had always been part of what we were about. But as that musical side of things changed, so did our feelings of the way our album artwork should look."

Rush had shifted themselves just far enough sideways to make a breakthrough. Moving Pictures carried long-term fans along without argument, while its accessibility - melodically, lyrically, visually - drove it high into the charts, onto radio stations, and ultimately to four million album sales.

As is traditional in rock'n'roll circles, there has to be an element of hand-wringing about success. Neil Peart had got his in first. "Limelight was Neil's way of expressing his unease at the way the band had become the centre of so much attention," Lee remembers. "I think all three of us had - and have - our own ways of dealing with this. Neil is the one most uncomfortable with it all. He still gets embarrassed when fans come up to him, although he is getting better at it. After all these years, Alex and I have learnt to take it more in our stride. We tend to goof off a lot. The irony of this song is that it expresses our concerns over fame and what it can do to you, while we were trying to make an album that would sell millions of copies. The confusion of being in a band, eh?"

Fast-forward three decades. Rush are still famous, although that fame is manageable, comfortable, and its rewards surely outweigh its burdens. Looking back, it's even more apparent than it was at the time that Moving Pictures was a watershed moment in their history, a record that signposted the future, and more, proved that they could exist in it. It remains their most memorable album, as well as their best seller. It's a debt acknowledged in Rush's current live set, about to hit the UK in May.

"The idea for doing the whole of Moving Pictures live came up when we were discussing what to do next," says Lee. "I was all for writing some songs and doing a new album. But it was Neil, of all people, who wanted to go out and tour. That surprised the hell out of us, because he's usually so reticent. Anyway, we talked it all through, and then someone suggested we could combine both. Go in and do some recording, take a break and tour. And we thought, yeah, that'll work. What clinched it was when the idea of doing an entire album in the set was mentioned. You know, I can't now recall who first mentioned this, but Moving Pictures was the one that made most sense. It's our biggest album in America, and it has Tom Sawyer, which is so iconic for Rush fans.

"We've kept playing almost all of the songs in our live set, so there was no problem with having to relearn anything. Apart, that is, from The Camera Eye. As I said earlier, that surprised us, because it was a song we never thought worked. But the way we revamped it made this come alive. One thing the tour did do for us was to make us aware of how good The Camera Eye always was. I'm so glad we've become friends with it again.

"The tour worked so well that [we wanted to take] it over to Europe in 2011. After all, that is the 30th anniversary year for it. [We are all for] delaying the new album one last time and taking this show on the road ..."

Film / DVD of the Year

As with most years, 2010 saw the release of some great rock-related DVDs and movies, ranging from retina-burning eye candy to touching documentaries. Due to an internet cock-up, readers couldn't vote, so here are the top five our writers decided were the best of the bunch.

#2: Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage

In a nutshell: Delving beyond the beer and soundchecks to deliver an intimate portrait of the Canadian trio. Daft, daring and, in Neil Peart's case, genuinely moving.

We said: "An affectionate and largely uncritical tribute, but one that goes beneath the surface often enough."

They said: "A wonderfully engaging and genuinely interesting career profile."

Critic's Choice - Songs of 2010

The albums of the year are just half the story. Here's the best songs of 2010 that DIDN'T appear on any of our favourite albums.

#1 BU2B

Rush (Single)

For a band with roots in the vinyl era, Rush are smart cookies when it comes to the digital age. BU2B was made available via iTunes as a taster for the upcoming Clockwork Angels album, along with another song called Caravan. Neil Peart reckons this 'un is "detached from the past, rooted in the present, and pointed toward the future". Based on a meaty Lifeson riff and with multiple changes of direction, the Canadians still possess the power to surprise.