10 Things You Gotta Do To Play Like Alex Lifeson

By Vinnie Demasi, Guitar Player, January 2011, transcribed by pwrwindows

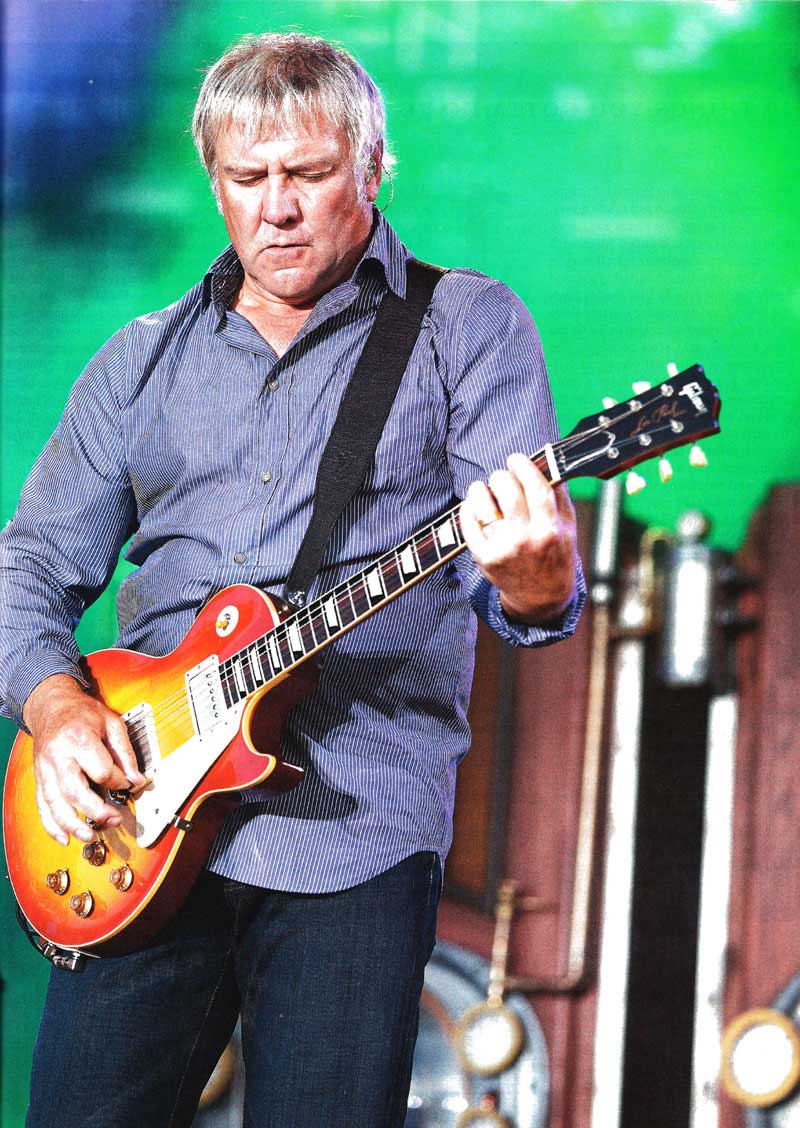

As a pre-teen discovering rock music in the early '80s, ax-wielding role models were plentiful but it was Alex Lifeson-and his band Rush-who motivated me to pick up a guitar. Something about the Canadian trio's ability to fuse heavy metal's visceral force with prog's intricacies, their Samurai-class chops, and lyrics that dared address topics outside the usual sex, drugs, and rock and roll dictum resonated with me in a way no previous band had. Factor in Lifeson's innate coolness-his long locks and Gibson doubleneck cutting an impressive figure-and I had my first guitar hero. I owned every album, sported a complete wardrobe of concert shirts and pins, and was a card-carrying member of the Rush Backstage Club. Hell-bent on rock stardom, I ordered a Rush Anthology songbook, hijacked my brother's Giannini nylon-string, and deciphered the G, D, and A 7 chord diagrams needed to strum "Closer to the Heart," the simplest song in the book. That first surge of rapturous musical discovery all but determined what I'd be doing with the rest of my life.

Okay, so I'm going a little fan-boy here, but I'll bet that if you're reading this, you have a similar tale to tell. In my 25 years as a music student, educator, journalist, and performer, I am consistently amazed by how many of my peers found their initial inspiration, validation, and identification in the music of Rush. Not to mention a whole generation of game-changing guitarists-Kirk Hammett, Larry LaLonde, Paul Gilbert, Billy Corgan, and John Petrucci, to name a few-who cite Lifeson as a prime mover.

Born Aleksandar Zivojinovic and reared in Toronto, Lifeson founded Rush with skin-pounding schoolmate John Rutsey in 1968. When bassist/vocalist/keyboardist Geddy Lee joined the fold, his wailing operatic singing and formidable 4-string skills solidified a heavy rock sound in the Grand Funk Railroad and Cactus paradigm. The replacement of Rutsey with drummer/ lyricist Neil Peart in 1974 heralded a more progressive, experimental direction for the band and, excepting a brief hiatus around the turn of the century due to personal tragedies in Peart's family, the fabled troika has endured, constantly changing, broadening, and redefining its sound. And in what is a lesson the music industry marketing machine hopefully takes to heart, the less easily categorized the band became, the more their popularity grew.

No surprise then that Lifeson, perhaps more so than any other rock guitarist of his era and stature, has a style and sound that's been constantly evolving and impossible to pigeonhole. And though he released a fine solo album, Victor, in 1996, analyzing his playing outside the context of Rush's music would be a bit like disassociating Mickey Mantle from pinstripes. Aside from his stringed accomplishments, Lifeson is also lauded for his sense of humor, amicable nature towards fans and journalists, and willingness to lay back while his virtuosic bandmates flaunt their world-class skills. A lesson in Lerxst (as Peart and Lee affectionately call him) certainly has something to offer 6-stringers of all ilks. So, get ready to...

1 BE A TONE TREKKIE

A rarity in the pantheon of guitar gods, Lifeson isn't identified with a singular sound. In fact, he can lay claim to multiple telltale tones at different stages of his career. On early records like Fly by Night and Caress of Steel, Alex relied mostly on a Marshall stack-amplified Gibson ES-335 for his beefy growl, with liberal doses of wah pedal for solos. By 1977's A Farewell to Kings, he'd switched to Hiwatt amps, added a doubleneck Gibson EDS-1275 and custom-built alpine white ES-355, and he began experimenting with chorus, as the addition of keyboards nudged the band's sound in a more lush direction.

1981 's Moving Pictures swapped Gibsons for Strats modified with Floyd Rose locking tremolos and Bill Lawrence humbuckers in the bridge position into Marshall combos. Here, Lifeson's leaner tone offered a clarity that complemented the band's increasing use of synthesizers and Moog Taurus pedals. Strikingly, Lifeson proved to be one of the most lyrical, evocative whammy bar artisans, as evidenced by the haunting solo in "Limelight," almost unanimously cited as his finest moment.

Throughout the '80s Lifeson willingly assumed a more textural role in the band's sonic schema, which now included sequences, samples, triggers, and electronic drums. Relying on a rack of Korg, Roland, and DeltaLab signal processors, Lifeson painted ethereal, abstract, and echo-laden soundscapes. His innovative (and artistically altruistic) efforts on 1984's Grace Under Pressure were acknowledged by GP readers who crowned him Best Rock Guitarist.

A later switch to PRS guitars paralleled a move towards a heavier, less electronically reliant sound. 2002's Vapor Trails was the first Rush album since the early '70s to be completely synth-free.

Currently, Lifeson rocks a stable of custom Floyd Rose-fitted Gibson Les Pauls-including some with a Fishman piezo system for acoustic sounds- as well as his original ES-355. His backline sports Signature Series Hughes & Kettner TriAmp MKII's and Core blade models, and his rack includes a TC Electronic G-Force and 1210 Spatial Expander. In Lifeson's capable hands, all this machinery is able to reproduce over three decades' worth of history-making tones.

2 HOLD THE 3RD

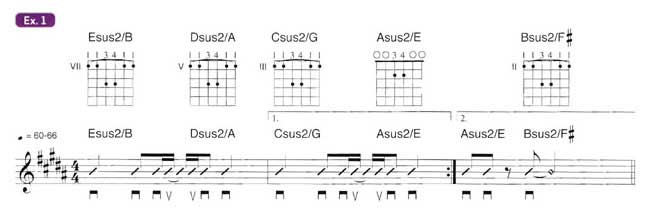

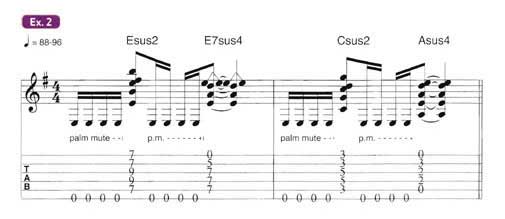

Intrinsically predisposed to deviate from the norm, Lifeson regularly sought out aurally rich alternatives to standard chord voicings. One favorite tactic was to substitute a harmonically ambiguous unresolved suspension (either a sus2 or sus4) for a given chord's 3rd- the note that determines major or minor tonality.

The moveable sus2 voicings in Ex. 1 are based on A-shape fifth-string-root barre chords, voiced with the 5 in the bass on the low-E string. Dreamily strummed on an acoustic, they evoke the introductory "Tide Pools" section to Rush's epic "Natural Science," or the intro to "Resist."

A compelling substitute for electrified root-5th-octave power chords, the quartet of sus grips in Ex. 2 will help you catch the drift of Lifeson's main riff to the classic "Tom Sawyer."

3 BE THE KING OF COOL CHORDS WITH OPEN STRINGS

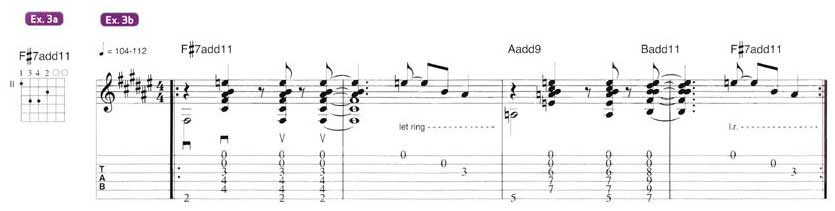

When illuminating Lifeson's use of cool chords, sus2 and sus4 voicings are just the tip of the iceberg. He regularly reaches for uncommon voicings with shimmery open strings. A listen to the first few bars of "Hemispheres" should establish why Alex pretty much owns the F#7 add11 shown in Ex. 3a. To finger this celestial-sounding beauty simply play an E-shaped F# barre chord on the second fret, but leave the first and second strings ringing open. Now slide it up the neck to a fifth-position Aadd9 and seventh position Badd11 and you're all set to tackle Ex. 3b, a classic Lifeson-style chordal salvo that harkens back to 1977's "Xanadu," but recently surfaced on 2007's "Far Cry." Remember to let the open first and second strings ring out.

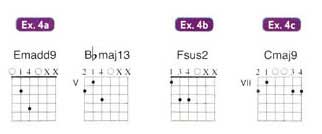

Played four times each with a lilting 6/8 arpeggio pattern, the brooding Emadd9 and Bbma13j fingerings in Ex. 4a yield the verse to "No One at the Bridge," while the Fsus2 in Ex. 4b is best experienced in the verse to "New World Man." In both instances, dig the ringing open third string.

For Ex. 4c, take a garden-variety G chord and relocate it to the seventh position leaving the D and G strings unfretted, and you've got the sprightly Cmaj9 that generates the first segment of marathon instrumental "La Villa Strangiato."

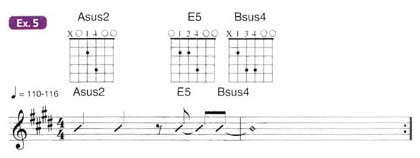

The chord stabs in Ex. 5 supplement the open first and second strings with a static B note on the 4th fret of the third string. best grabbed by the pinky. Play it as written, or rearranged Bsus4, Asus2, E5 to replicate the sequence that follows the opening riff of "Limelight."

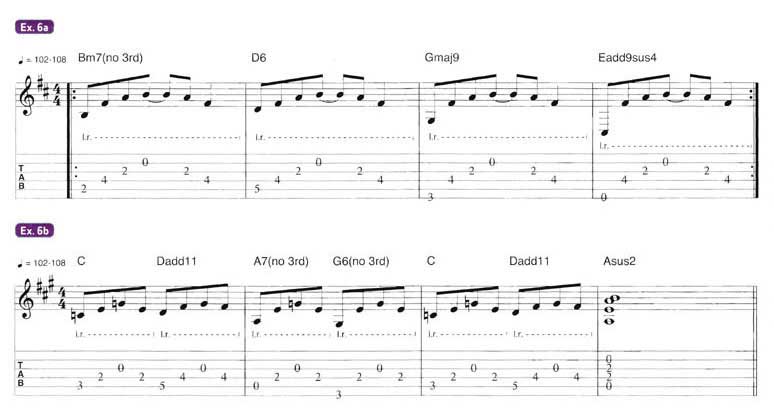

While Examples 6a and 6b don't reference any particular Rush song, these arpeggiated pretties-employing either an open second or third string as the common thread between each chord- should offer some insight to the chordal construct on "Animate," "The Pass," "Resist," and countless others. Remember to hold the chord shapes in place and let the notes ring out.

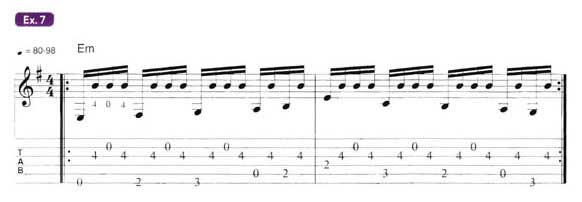

4 ROLL THE DRONES

As a teenager; Lifeson copped a few classical guitar lessons and it's easy to detect a hint of Spanish nylon-string flavoring in Ex. 7. As in Ex. 5, he's making liberal use of a droning open second string against a pinkyfretted B on the third string, only here it's being played out against a Tarrega-approved melodic bass note pattern. Variations of this rolling lick can be heard during the third vocal section of "Tom Sawyer" or as a recurring theme in "Natural Science."

Lifeson plays these electrified and picked, but to be awed by his acoustic fingerstyle nylon-string prowess, check out the unaccompanied solo "Broon's Bane" from the live CD Exit ... Stage Left.

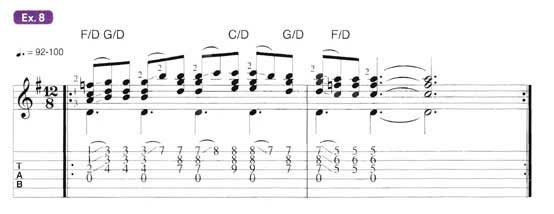

5 KEEP THOSE TRIADS ON TOP

Having one of rock's mightiest rhythm sections to cover the low end means Lifeson isn't always required to fill space, and is thus free to explore minimal chordal voicings. Like Pete Townsend-a major influence on Lifeson and a guitarist who also sparred with a brawny bassist and drummer-Lifeson often grabbed triads voiced on the top three strings. A stellar example of this is the guitar solo section of "Freewill," where Lifeson alternates between phrases of serious scalar shred and a strategically placed melodic chord figure similar to Ex. 8. Despite the breakneck tempo and fairly clean guitar sound, the intensity never wanes due to Lee and Peart's supersonic accompaniment. (Hint: Fret the first chord with your second finger on the first string and keep it in contact with the string as you slide the shapes up and down the neck.)

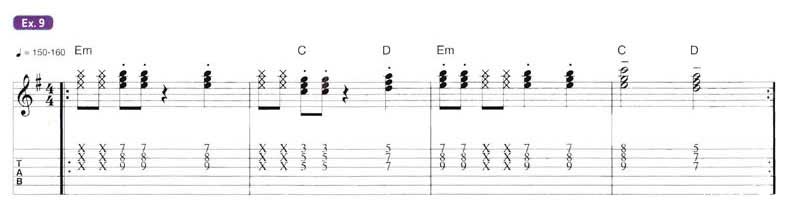

One of the few hard rock acts of the '70s to gracefully make the transition to the '80s, Rush were quick to acknowledge and assimilate the reggae influence in the music of the Clash and the Police. Dubbed "proggae" by fans, Rush songs like "Vital Signs," "The Enemy Within," and "New World Man" are characterized by Lifeson's tight, offbeat highstring chord chops like those in Ex. 9.

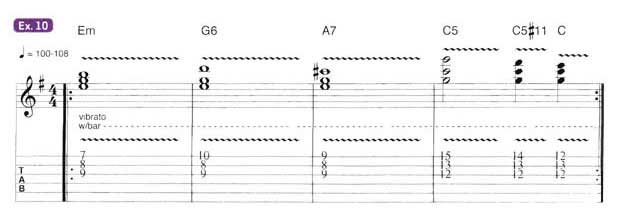

By the mid '80s, Lifeson was seeking new ground to stake out in Rush's musical landscape, now heavily populated with synths, electronic drums, and triggers. Willingly assuming the role of sonic obbligatist, he again sought out voicings on the top three strings only now, incorporating nontriadic color tones. Try playing the sustained chords in Ex. 10 with liberal doses of chorus, long delay, and whammy bar vibrato to get a feel for Lifeson's approach in "Red Sector A" and "Distant Early Warning."

6 RETHINK THE RIFF

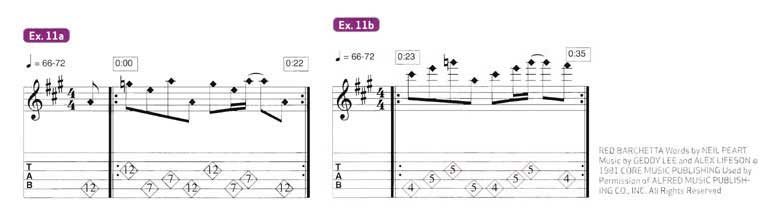

The term "guitar riff" generally conjures an image of heavily overdriven low-string sludge, and while Lifeson can pile drive with the best of 'em (dig "Working Man," "Anthem," or "The Temples of Syrinx") , some of his signature parts were written while thinking outside the blues box. One of my all-time favorite Lifeson moments, transcribed in Examples 11a and 11b, are the two melodic sequences of harmonics during the introductory buildup in "Red Barchetta." They sound sweet unaccompanied but really bloom when played over the A-F#m7-G-D progression implied by Lee's bass line.

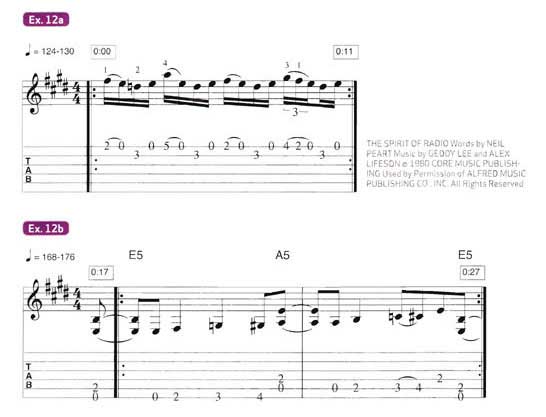

Ex. 12a is the opening salvo of "The Spirit of Radio," a series of rapid-fire pull-offs on the top two strings that's addicting to play, sounds as right as rain, and is a hellacious workout for all four fingers on your fretting hand. No examination "The Spirit of Radio" would be complete without a mention of the jaunty unison guitar/bass main line. Even though it's text book low-end fretwork, I proudly present it here for your riffing pleasure in Ex. 12b.

7 REDISCOVER THE RIFF

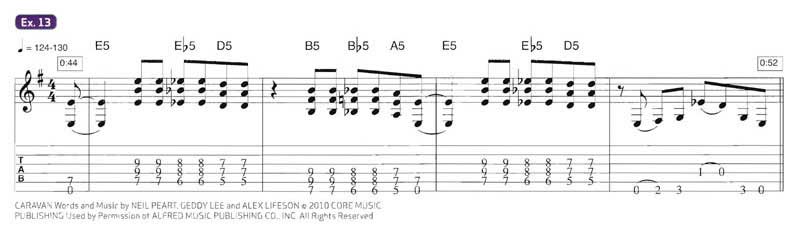

Present-day Rush is hallmarked by a leaner, stripped- down sound that still manages to retain some of the more progressively daring and sonically exploratory tendencies from their past. But when it comes to dishing out some serious kick-ass crunch, Lifeson is still a heavyweight champ. This is amply demonstrated in Ex. 13, the chromatic-laden crusher that powers their latest release "Caravan."

8 BE THE LIFELINE

In the recent Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage DVD documentary, Death Cab for Cutie's Jason McGerr deftly observes that even at their most complex, Rush always provided a musical "lifeline" listeners could latch onto. I strongly suspect that Lifeson's playing is that very lifeline. No finer example of this exists than "Jacob's Ladder," an unusually structured, largely instrumental three-part rock and roll tone poem that depicts sunlight breaking through a thunderstorm.

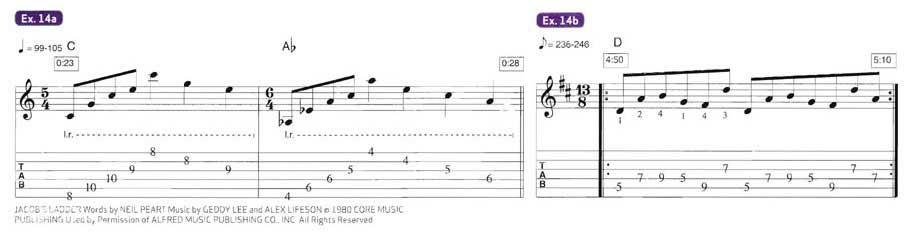

The initial section of the song is underpinned by alternating bars of 5/4 and 6/4, counted one-and-two-and-three-four-five, one-and-two-and-three-four-five-six. Here, Lifeson arpeggiates a C-Ab,-F-G-Ab,-E chord progression voiced with E-shaped barre chords- the first two bars of which are shown in Ex. 14a-over Peart's sprawling linear snare drumming. Remember to keep alternating between bars of five and six beats, while cycling through the chords.

During the track's triumphant ride out, Lifeson kicks in with Ex. 14b, a knuckle-busting mothertrucker in 13/8. He then alternates it with two bars of the same riff in F# starting on the 2nd fret of the sixth string, while Lee and Peart ratchet up the intensity, cycling through increasingly complex syncopated rhythmic settings. In the hands of a lesser band, the song might've been a shambles but Rush turn it into something unique yet highly accessible.

9 GRAB THE LIMELIGHT

I've given major airtime to Lifeson's celebrated chordal constructs, but he's also one of the most unique and compelling lead guitarists in rock. Early solo flights like those in "By-Tor and the Snow Dog" and "The Necromancer" combined equal doses of chops, intensity, and melodicism, but it wasn't until Lifeson began articulating heavily with a whammy bar that his illustrious improvisational voice emerged fully matured. Grab an earful of the fluid lead breaks on "Emotion Detector," "Tom Sawyer," "The Analog Kid," or "Limelight" to hear how Lifeson's intuitive mastery of phrasing transcends scales, notes, and rhythms, and vibes on pure emotion.

Ex. 15a recalls the languid beginnings of the transcendent lead break in "La Villa Strangiato" with an attention-grabbing pre-bend and release articulated with a volume-pedal swell. The modally melodic Ex. 15b has its lineage in the solos to "Limelight" and "Marathon" as well as the melodic figures of "Resist." Use the whammy bar to give each note a bit of expressive vibrato. (Hint: shake each quarter-note with a triplet rhythm.)

Another "Limelight"-styled highlight, Ex. 15c starts with a serious dive-bombed open second string. As you quickly pull back up on the bar, sound the 12th fret harmonic without picking again. For the last two notes of the last bar, fret the B on the 9th fret of the fourth string but sound the A before it by dipping the whammy down a full step.

10 BE THE COOLEST GUY IN THE COOLEST BAND EVER

I'm writing this on a day that Rush have again been snubbed by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's nominating committee. While accolades and awards aren't really what music's all about, it's still surprising the Hall has yet to officially recognize them as one of the all-time greats. Their 30-plus years of sustained success, legions of fans, sold-out arena tours, 24 gold, 14 platinum, and three multi-platinum albums, and hordes of professional musicians who regularly cite them as an influence and inspiration certainly suggests otherwise. And despite being called "Earth's Hardest-Rocking Nerds," by Rolling Stone magazine, Rush are the epitome of coolness. They are three lifelong friends who dropped out of school to make their dreams happen, created a sound that was entirely their own, and have stayed completely true to their muse. They responded to their record company's annoyance at the epic suite of the second side of their then-latest album by putting an epic suite on the first side of their next album, wrote about social injustice, personal responsibility, and youth alienation, and carried themselves with good grace and self-deprecating humor throughout.

As for Lifeson being the band's coolest member, well that's just my own personal prejudice. Still, I'm sure I speak for many when I say, "Alex, we love you man!"