Close Up On Neil Peart

By David West, Rhythm, August 2011

It's been my life's tangent," says Neil Peart on the subject of the pursuit of excellence. Since he joined Rush back in 1975, Neil has been the poster boy for prog - disciplined, metronomic and powerful. When you meet him in person it is easy to see where the power comes from - he's an imposing guy, a fact often obscured by the gargantuan drum kit that usually surrounds him. Rhythm met up with Neil backstage at London's 02 Arena and, watching Rush onstage later that night, it is clear that something fundamental has changed. The band known for meticulously recreating their studio recordings live on stage are jamming. More than 35 years since Neil joined the world's foremost power trio, Rush are still pushing themselves and breaking new ground.

Neil's first role model for drumming excellence was Gene Krupa, who Neil encountered in the movie The Gene Krupa Story starring Sal Mineo.

"Even watching it now, it was so well done," says Neil. "Sal Mineo was coached by Gene, the opening sequence is a beautiful overhead shot of Gene actually playing, very inventive for the day, and then all the drumming is Gene. Sal Mineo mimics it so well that it really works and that was the inspiration. 'Wow! Being a drummer is romantic and dangerous and glamorous.' It had all that, it had everything, so that got me curious."

At 13, Neil convinced his parents to let him take lessons, but he had to wait to play real drums. "My parents gave me lessons, sticks and a pad," he says. "They said, 'If you do this and practise every week for a year then you get drums." That's still what I tell parents. 'Oh, I'm thinking of getting my kid drums.' Don't get your kid drums. Get them sticks and a practice pad and lessons and if they do it for a year then they're serious, then get them drums. It's so obvious but a lot of them look at it like a toy these days, especially with the Rock Band thing. I've talked to parents who've said, 'I don't want them to get that serious, it's just for a toy.' I'm like, 'A drumset - a TOY?!' It's hard not to get irate about that because it's been the focus of my life and the tools of my trade."

Neil's mastery of his trade has made him the toast of his peers in the rock community. His career is littered with classic performances and brilliantly crafted drum parts that are intrinsic and vital to Rush's musical identity. Yet despite his success, Neil remains a student of his art, reinventing his playing virtually from scratch in the '90s with drum guru Freddie Gruber and recently undertaking another course of study with Peter Erskine. The continuing evolution of Neil's abilities speaks to the truth of the maxim that success is not an act, but a habit. The pursuit of excellence is a journey, not a destination.

Neil, what were the challenges you faced early on in your development?

"While I was playing along with records, all the frustrations were tempo things - getting excited when you playa fill and then getting tired after. I always joke about this with young drummers. They get excited and speed up when they playa fill and then they get tired and slow down. It's so natural, right? And it's a lifelong pursuit to develop good time. I'm talking about spanning four decades for me, first of all just trying to play the tempos like the records, then being in the studios and having to deal with click tracks and sequencers from the late-70s and playing in mathematical time, that was my pursuit. to be able to do that both in the studio and live. I learned a lot about the click track, how you can make it breathe. It doesn't have to be a mechanically driven clock at all, it's a guide. You can push and pull an amazing amount on those tiny increments of click pulses. But that led me into a trap by the mid-'90s with sequences and click tracks that I felt were metronomic in the bad sense, I was starting to feel stiff and that's when I studied with Freddie Gruber because I saw Steve Smith play. In the mid-'80s we worked together on a Jeff Berlin record so I'd seen Steve play and knew that he was great, but when we were doing the Buddy Rich tribute, he came in to set up and just started playing. I said, 'What happened to you?' It was so beautiful, so musical, so crisp and elegant. And he said, 'Freddie.'"

So what did Freddie bring to your playing?

"I met Freddie around that same time of the recording of the Buddy Rich tribute. We became lifelong friends and started working together to loosen my playing up and make it a dance. That's what his coaching was all about. It was all physical, not musical. He's not the kind of teacher who teaches you how to play the drums. He teaches you how to dance on the drums. At that time, '95 or so, I'd been playing then for 30 years. 'Am I really going to stop now, practise everyday with these exercises he's giving me, go back to traditional grip, the right end of the sticks?' Because I'd been playing butt-end with matched grip for a long time by then. He had me moving the snare drum up, the bass drum farther away - so counter-intuitive. I always thought, get everything as close as you can and then you have the best reach on it - but in fact no, it's your area of motion. It's better to have your bass drum, toms, ride cymbal a little farther away, so it was completely re-inventing the way I play the instrument."I had to say, 'Can I do it and is it worth it? Can I go down to the basement every day and practise again like I did when I was 13? If I can commit myself to that, will I be rewarded?' I decided it was worth the try and did that for about a year and a half. The band happened not to be working because Geddy and his wife were having a baby so it was perfect timing, such synchronicity, finding Freddie, just the right guy. He really helped me in that way of loosening it all up again within the framework and carrying forward with the accuracy and it was still my playing. A lot of people, even my band-mates, couldn't tell the difference, at first until they played with me and then they noticed the clock was different just from that new physical approach to playing the kit. It was such a subtle approach that our co-producer at the time Peter Collins said, 'Well it still sounds like you: I was kind of disappointed but then when the other guys played with me, they noticed that the clock was different, as they do now because I've entered another period that kind of echoes that."

So what has been the focus of the next part of your journey?

"In '07 I studied with Peter Erskine because I was doing a Buddy Rich tribute concert and I wanted to take my big band drumming up a level. I decided Peter Erskine was the guy and I went over to his house with my sticks feeling like a 13-year-old again. You're surrendering to a teacher, there is no sense going in there with attitude, or why bother? I was going in there to the master and in fact I told him at the time, 'You know, as far as I'm concerned you're a surgeon and I'm a butcher.' He said, 'You're not a butcher!' I said, 'No, I'm a good butcher but I'd just like to get a little more surgery into it,' and he helped me with that eloquence and time sense. I came in from studying with Freddie with a lot of physicality between beats. Peter had me start by playing quarter-note ride beats and I had this thing from Freddie where I was doing a little flick of the wrist in between. Peter points, 'What's that?' I knew he studied with Freddie so I was kind of confused, but I said, 'That's time-keeping.' He said, 'No.' He points to his heart, 'Timekeeping is here. Own the time.' It was an evolution I was able to bridge. Now I feel that flick of the wrist between each beat. I practised for six months just on the hi-hat alone with Peter. There is a Roland device with Quiet Count, where you get two bars of click and two bars of silence so I started practising to that. I've heard from a lot of other drummers that it can make you mental, how hard that is. So every day I start with a slow tempo and a fast tempo with that approach - two bars of click, two bars silent, and try to come in on time. Especially with slow tempos it's so hard but so good, and I played nothing but hi-hat every day for six months. It never got boring because I was exploring and checking things out at the same time. I got tons of new ideas during these tempo exercises."

So how have you applied this to Rush?

"Coming back to the pursuit of excellence, I felt such a growth in time-sense - and that gives me more bravery in fills and in improvising that I can go so much farther outside now because it's almost given me a duality of thought lately that I can see what's happening and what ought to be happening. If there is a little train wreck among the three of us I can suddenly run on two tracks now. I can be playing what I know to be right but if one of the guys is half a bar out I can say, 'Okay, if I drop that half bar, we'll all be together again.' Even sometimes if I make an error of execution that throws me off, I can still hear the time and that's 45 years of getting to that stage to be able to do that."

Your live solos continue to evolve. How do you avoid getting stuck in a rut?

"Freddie had defined me as a composer. He said, 'Look, when you play, you're composing.' And I accepted, yes, I'm a compositional drummer and when I did the Anatomy Of A Drum Solo video I defined myself that way - 'I composed this solo and I play variations within the movements but it is a composed piece.' Then right after that I went, 'Well, I want to improvise. I don't want to be just a compositional drummer.' So I deliberately set out to learn that, within the context of my solo, making the first half of it improvisational over three different ostinatos, and then the second half was composed so I know it is always going to resolve into something from the audience's point of view."Pure improvisation, everybody knows, is inherently risky. I remember seeing the Grateful Dead years ago and Mickey Hart met me before the show. He said, 'We had a really good show last night so we probably won't have another one for the next three or four days.' That's just the cycle that is necessary if you devote yourself to improvisation. I improvise within a framework but I've been able to take myself so far out of my former comfort zone with that kind of nurturing over time from teachers like that and inspirations. Have you heard the Crimson Jazz Trio records Ian Wallace made? There is an old King Crimson tune called 'In The Court Of The Crimson King', a long slow legato thing, well he did a Latin arrangement of it with an ostinato that I now know is called 'Xaxado', because I found out from Brazilian drummers when I was there. I sat down with this thing, I'm trying to figure out, where does the hi-hat go for a start? There's a Buddy Rich tune called 'Nutville' that Steve Smith played on the tribute album and it has that exact same rhythm, the Xaxado, so I just started playing with that. I wanted to use it like the waltz has been for me - as an ostinato that I could use every single day. I sit down at my warm-up kit and I start with the waltz. At the same time, during casual playing time, I was working on another kind of polyrhythm ostinato with downbeats and upbeats combined. I've tried and failed to really understand what I'm trying to do with this but it's like playing two songs at the same time. It's that double-track mind I was talking about before, playing a strictly downbeat pattern with bass drum and hands while the hi-hat is always playing the upbeat - not just playing it but feeling it. It's the tension between upbeat and downbeat that reggae music has, for a good example - that's what I'm trying to incorporate into these polyrhythms where two feels are incorporated, not just the notes. That became a whole course of experimentation and study and now is part of the second part of my solo. I move through the waltz ostinato and I never start with the same figure twice.

"Inevitably every improviser finds that you find something you like and you want to do it again the next night. It's hard not to - that really worked, it led into the other thing so great, and the audience loved it and all that - but to be true to the spirit of it you can't let yourself do that."

Aside from the improvisation, has your playing changed in other ways?

"My band mates and I were talking the other night about how the time-sense we have now is different from what we had before as a band. I feel it in myself, through working with those teachers and continuing to push myself in different directions, being comfortable with improvisation has made me a better composing drummer, for that reason that I can hear those two things at once - what is and what might be - because that's what you have to do. That's why now, when we're playing a song and something goes wrong, I can still hear what should be happening and then what is happening and compare and correct it. I'm sure that's how I've learned that, from forcing myself into that open zone, that dangerous zone, every solo every night and even with the newer songs that we're working on I'm doing more and more of that. As we play them live there are fills I change every night. I never used to do that. It's a new frontier for me, and how wonderful after 45 years of playing, not only do I have new frontiers technically but the band comes with me on those, and through all of our stages that each of us has gone through musically we have all grown together like that. At the very pulse of our music we have something new there that we didn't have before. We were discussing something quite different about one of the shows and I was saying about tempo control and the way I judge the tempo of a song by the vocals. More and more I'm able to do that because I can get out of what I'm doing. Again, improvising gave me that so I can go listen to Geddy and his phrasing because that's how I judge tempos a lot now by the vocal phrasing, how it falls. You can tell so easily how it should be. It's such a valuable lesson to learn, get the tempo from the singer."

So what drives your actual timekeeping?

"Getting back to the central pulse thing, I know it's from my bass drum. That is the fundamental that Geddy hangs his bass parts off of, and thus the band hangs from in a very real sense, or is built from. The bass drum is the heart of it and I know that I feel and play and position those bass drum notes a little differently now. It's so subtle it couldn't be measured, using anticipation, using tension, pushing a little bit on purpose."One of the older songs that we're playing, 'Presto', is from '79 and I don't know if we've played it ever, or we haven't played it for 30 years. It's one of those that we play so much better than the record in a feel sense, a rhythmic sense. I was saying to my band mates how much better that song is now than it was on the record and Geddy said, 'Yeah, we have a so-much-better rhythmic pulse now than we did back then.'

"The interesting thing is, it's the only time in my life I've been asked to speed up. Stewart Copeland and I talked about that because we're both pretty energetic and when you get excited you speed up, so I've always been, 'Pull back!' It's what I've had to learn to do to control time, and no one has ever asked me to speed up. Geddy and I were discussing that song and the bridge section, he said, 'The tempo is right now but I think it would feel better to push it forward a little bit: and I did. To be able to control that is so gratifying as a drummer. You grew up as a kid insecure about your timekeeping and getting crap from other band members about it as every drummer does. Let this be a breath of hope because I went through that as much, or more than, other people and got over it now to where I have that level of understanding and control of time. It feels so good, to be able to do that, to push and pull things, or if I listen to a live tape and I hear a song that is leaning a little too far forward I can pull it back an infinitesimal notch now. That's the pursuit of excellence, to be able to do that in live performance."

Is that what keeps you on the road after so long?

"The real test of a musician is live performance. It's one thing to spend a long time learning how to play well in the studio but to do it in front of people is what keeps me coming back to touring, because I really don't like it but it's necessary. For me to call myself a musician it's necessary to play live and it rewards so much, not just in the pay cheque sense but what it does for my playing. I feel it through a tour, I feel it at the end of a tour, all that I've gathered and especially now that I am improvising so much, all that I am exploring, all the new ideas I have. I try not to repeat myself in fills in all the Rush songs unless it is something very simple or something I feel is my own characteristic thing, then I'll repeat it, but otherwise I try not to as a matter of principle.

In fact, on the previous record, Snakes And Arrows, our co-producer Nick Raskulinecz wanted me to play my Latin-style ride beat that I used on all the old songs, it was one of my signature things. I said, 'No, I don't do that any more,' but then he convinced me it was the best thing for the song. Okay, I'm making a choice here, I'm not going to fall back on a pattern just because it's comfortable but the producer asked me to and, without argument, it does work. For a while that was my thing and I used it a lot because it was so propulsive and it also gives a nice fluid flow. People talk to me about playing on two ride surfaces, alternating between ride cymbal and china cymbal or the X-hat I have. If I want a quarter-note feel on the hi-hat, I play the eighth off of it on the ride so it gives it a nice lilt. Those are just little devices to get more fluidity into my playing. You try to go against what comes naturally sometimes, or I do at this point in my life. Intuitively I am very organised and arranged so I try not to be."

For someone with your reputation who is so widely respected by their peers, was it difficult to take such a big step back and just play hi-hat?

"It shouldn't be. There is nothing I would rather have than the respect of other musicians for what I do, but respect is something you have to earn continually. A lot of times people only respect dead musicians because they can't let you down. Everyone has had that experience of being a fan of someone who suddenly really lets you down. I feel that it is something that constantly has to be earned. I was going to say it's a burden but it's not, it's a responsibility. Like playing live, it's my responsibility to perform as musician. As a musician it's my responsibility to get better and if people are admiring the work I do then that's even more inspiration to improve and to take it up a notch and not repeat myself. The hunger for improvement and exploration and all that really does derive from the acclaim. I know that people give me that respect so I feel I have to earn it."

Neil's Drum Guru

Neil Peart on drum guru Freddie Gruber, the man who taught him how to 'dance on the drums'

Freddie Gruber was born in New York in 1927. Growing up in the Bronx, he was immersed in the Afro-Cuban music of his neighbourhood, home to a large immigrant community, which Freddie says gave him an innate feel for Latin rhythms, while his feel for swing is attributed to his tap-dancing as a child. "Buddy Rich was an excellent soft-shoe dancer," says Neil.

"Freddie is 84 now, he's only 10 years younger than Buddy would have been, and he comes from that same vaudeville background where you had to learn how to do everything. That's part of the heritage. Drumming and dancing are pretty close, but it's funny how so many drummers are bad dancers, myself among them, but it's another kind of dancing."

Freddie became well respected in the New York jazz scene, playing with Billie Holiday's pianist Joe Springer, band leader and crooner Rudy Vallee and boogiewoogie pianist Harry 'The Hipster' Gibson.

Right at home in be-bop, thanks to a fluency in polyrhythms, in the late '40s Freddie was playing with heavyweights like Zoot Simms and Charlie Parker but, like Bird, he battled with heroin addiction in the '50s and '60s, which put a stop to his playing career and almost killed him before he cleaned up.

From the '70s, drummers began to seek him out as word spread of his remarkable, if unorthodox, approach to teaching. Over the years, the likes of Peter Erskine, Adam Nussbaum and Anton Fig have sought out Freddie in their pursuit of excellence.

"Fifteen years later I'm still growing from what he taught me, his sense of what I needed as a student," says Neil. "Among his other students, if you think of Steve Smith, Dave Weeki, Ian Wallace, all of them very different drummers with different goals, but he can tell you how to get where you're going. He can intuit what you need to be able to do that."

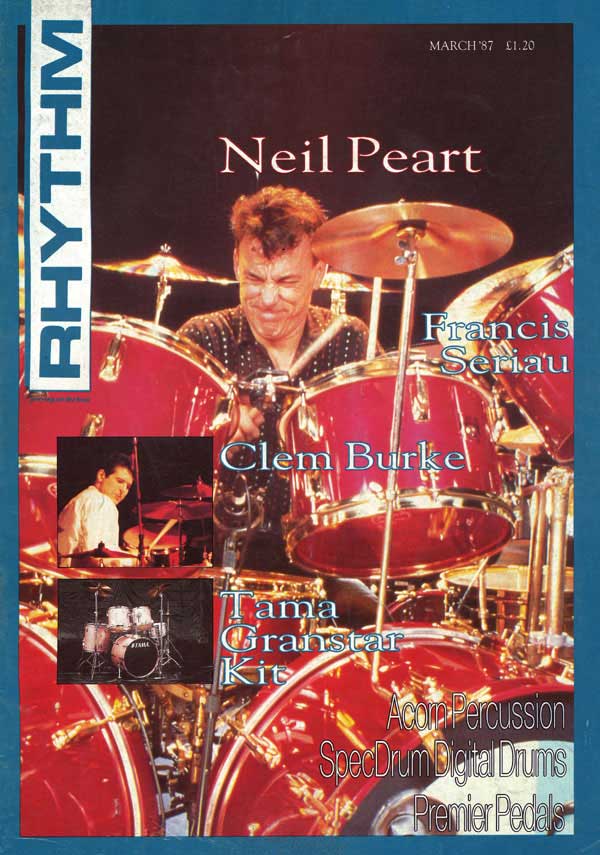

Neil's First Rhythm Cover

Neil's pursuit of excellence has brought him a long way throughout his career. Here's what he had to say about it in Rhythm almost a quarter-century ago, in March 1987.

On the hardest thing about drumming

"I think the hardest struggle for most drummers seems to be developing a really good time-sense and a strong tempo. Double-stroke rolls and things like that were all very difficult for me to learn. It took a lot of time. But, years and years went into searching for a better time sense and a more accurate tempo."

On his appeal to drummers

"I think a lot of my appeal lies in the fact that I overplay like crazy and I'm allowed to, within the context of this band. I'm lucky in that we've always been very free in areas we've been able to explore. There's never been a damper put on me that I know most drummers have to deal with. I think the reason why a lot of drummers might like my work is because I get away with that and in their situations they might not."

On being a busy player

"I know that other musicians who aren't drummers might say, 'Oh, he's too busy, why doesn't he just shut up and play the beat. Well, that's their opinion. I can understand it, but personally I've always found active drumming to be very exciting."

On his kit

"I look at it as my own personal orchestra that I can orchestrate and conduct. When it comes to creating drum parts for songs and in the sense of expressing myself musically, I find I need a greater palette of colours from which to draw. But there are two sets of values there; from a drumming point of view and from that of just enjoying it. I'm happy enough with a small kit, but from a composition, arranging and expression point of view, that's where I like to have more to deal with."

On challenging himself

"Particularly when working on new material I want it to be a challenge. Sometimes I'll put a drum fill in a song that I really can't play, but I hope to practise it enough so that by the time I record it I am able to play it. I hate to repeat myself too. It drives me always to be looking for new combinations and new rhythmic approaches."

The Pursuit of Sound

Excellent drumming requires an excellent sound and for Neil the process of working with drum and cymbal makers to find those sounds is one of collaboration and inspiration. "With Sabian it was the development of the whole line of cymbals that started from a piece of metal on a stand," he says. "Mark Love and I tried everything possible to find out what I liked the best and what worked the best for me so that was how in-depth that process was of metallurgy and music. I was having a discussion with John Good at DW one day and I was saying that when we used to open shows in those days a lot of drummers were using 24" bass drums.

I used to love the way they sounded out-front through the PA but I never liked the way they played so I always went with a 22". John said, 'What about a 23"?' I said, 'There's no such thing.' And he had to make the shell, get the Remo drum head company to make 23" heads and all of that came out of that discussion. That's how eager he was to try it and of course the 23" bass drum not only works so great for me but a lot of other drummers are finding that too. I love the collaborative aspect of that."

Neil's Tech Talks Gear

Neil Peart's long-time drum tech Lorne Wheaton gives a guided tour of The professor's Time Machine

"Neil's been playing Drum Workshop since 1995. The first tour he did with DW was the Red Sparkle kit on the Test For Echo tour and we used that for Vapor Trails too. Then we went into R30 (the Rush 30th anniversary world tour) with the custom-built kit with the Rush logos, then the Snakes And Arrows tour, and this is where we've ended up, with the new Time Machine kit. Louie [Garcia, DW master craftsman and artist] spent so much time building and finishing it.

"The shells are one-ply of walnut on the outside which we match with the deck on the riser. They're all maple shells and a mixture of VLT, VLX and X-shells.

"We have Sabian brilliant Paragons. I clean Neil's cymbals every day. With the old natural finish Paragons, after about six or seven shows I'd pretty much have them down to a brilliant finish anyway from buffing all the metal out of them. The only drawback of that is they'd break because you're drawing metal out every time you're cleaning them. With the brilliant finish they buff them at the factory and make them so durable. I've had this set of cymbals since the start of this leg of the tour and we haven't broken one. And he hits very hard. We've got the gears on top of the cymbals because we have an overhead camera and it plays to the steam punk theme. We use all the same type of graphics on the shells, copper and chrome leaf inlays.

"We're using Remo clear heads on toms and an Ambassador X coated on the snare now. They're a lot more durable. It's all DW hardware, copperplated. The gauges and dials were all Neil's idea. DW were kind enough to run out to the closest hardware store to try and get some of this stuff and send it off to the platers. All the video panels on the riser are from a guy called Greg Russell and a prop company in Hollywood.

"Round the back it's all V-drums, the TD-20KX. We use the stock pads, the same that we've been using since the Vapor Trails kit, but I take the triggers out and have DW build shells that we mount them into. The rack is pretty antique. We're not using laptops, it's all hard drives and actual samples. I also use Roland Midi Displays. I can actually see Neil play the midi note on the V-drum stuff while he's doing his solo. You can't find them anywhere. Not even on eBay!"

Neil's Kit

DRUMS

Drum Workshop Collectors Series in Steampunk finish: 23" bass drum (VLX shell series); 8", 10", 12" and 13" rack toms (X-shell series); 15" (x2), 16" and 18" floor toms (VLT shell series); 14" x 6 1/2" VLT series snare; 13" X-shell series piccolo snare

CYMBALS

Sabian Paragon Brilliant finish cymbals with a custom Steampunk design applied by the factory: 10" splash (x2); 16" (x2), 18" & 20" crashes; 14" hi-hats; 22" ride; 14" Artisan Brilliant X-hats; 8" splash (mounted above the hats); 20" china beneath a 20" Diamondback china (cymbal with the jingles and rivets); 19" china

HEADS

Remo Clear batter heads on toms, Remo Ambassador X snare batter heads, Powerstroke 3 on bass drum

ELECTRONICS

Roland TD-20X V-drum triggers (mounted in DW Collector series shells), Roland V cymbals and hi-hats, Dauz trigger pad, Fat Kat trigger pedals, Mallet Kat Express (Midi Marimba), Roland V-drum TD-20KX percussion modules (x2), Roland XV 5080 samplers (x2), Glyph hard drives, Roland Midi Displays, Behringer line mixer, Monster power conditioner

PLUS

Copper-plated DW 9300 series hardware, 5000 series DW hi-hat pedal, 9000 series DW double bass drum pedal; Pro-Mark Neil Peart Signature 747 drumsticks; 9ft x 9ft Octagonal rotating drum riser in Steampunk finish; squirrel cage fans (x2, to cool his hands); Kelly SHU internal kick drum microphone mount

In Neil's 'Bubba Gump' warm-up room

Drum Workshop Collector series kit in Aztec Red fade to Black finish: 18"x16" bass drum, 12" rack tom, 13" and 14" floor toms, 13" piccolo snare drum; selection of DW 2000 series hardware; and assorted Sabian Paragon cymbals

Slingerland Neil Peart Replica Kit

Sam Kesteven tells Geoff Nicholls how he assembled his 1970s kit inspired by this month's cover star Neil Peart

Neil Peart is known for his many spectacular kits and for the exceptional devotion of his fans. London drummer Sam Kesteven has painstakingly assembled this '70s Slingerland from items obtained through eBay, mostly from the USA. He explains, "When I was 10, in 1983, my brothers took me to see Rush at Wembley. It was the Signals tour and Neil was playing the Tama Candy Apple Red kit. My eyes were glued to the drums all night and so my obsession began. I've spent the last nine months putting together this replica 1970s chrome-over-wood kit. It's not been easy as they are specific sizes and I could not find them in the UK."

In fact Sam bought three Slingerland Niles badge kits (for a bargain total of £700) - two kits in chrome wrap, but one in black wrap. From these he was able to configure the kit seen here. "My kit is based around two Slingerland set-ups that Neil used. The finish is the same as his chrome 1974-77 kit, but the configuration is of his 1977-79 black-chrome set. The set-up is as follows: two 24"x14" bass drums, 18"x16" floor tom, 15"xl0" (still waiting for 15"x12"), 13"x9" and 12"x8" double headed toms, 12"x8", 10"x7", 8"x5 1/2" and 6"x5 1/2" concert toms (the latter with UK custom-made maple shell), 13" and 14" timbales, 14"x5 1/2" snare. There's also an 18"x12" gong bass drum. Neil didn't use one until the Tama years, but I wanted one and this is the closest I could find. It should really be 22"."

The black bass drum has been re-covered in chrome plastic wrap, acquired from the USA. For the snare, Sam took the hardware off an old Slingerland metal snare and fitted it to a maple shell, covered in chrome wrap. "I will eventually invest in something more authentic," he says. "The stands are a jumble, mainly modern. The trickiest to replicate are the stacker stands. They should be Tama Titans, but I've used Premier Triloks to stack the 18" crash above the 22" ride and to mount the cowbells under the 8" splash. The easiest bits to find - for which our friends in the US have to pay big bucks - were the Premier bass drum cymbal mounts and arms, one for each bass drum.

"The cowbells are two old LPs, plus a new Pearl Tri-bell. The original Gon Bops Tri-bells that Neil used are rare, as are the super-long chimes." Cymbals are A Zildjians, although not exactly following Neil's set-up. Likewise, Sam has found it difficult to copy Neil's exact head selection.

"My intention is to advertise the kit for hire by the hour in a rehearsal studio so that anyone can play it, like I always wanted to. I'm pretty sure this is the most faithful Neil Peart replica kit in the UK and I'd like to share it."