Neil Peart: The Modern Drummer Interview

By Michael Parillo, Modern Drummer, December 2011, transcribed by John Patuto

A new DVD puts us right on stage with the Rush rhythmatist, for a detailed throne-side look at drumming masterpieces from his fruitful career. Here, MD digs deep into Peart's musical travelogue, including his recent excursions into the unknown. This Time Machine makes all stops ....

Artistic greatness rarely comes easily. Talent, though hugely important, will get you only so far. Picasso, for example, might have shown an exceptional aptitude for figure painting as a teenager, but pure ability was hardly enough. His curious mind never rested. Innovation and exploration were paramount, and Picasso refused to sit still. Perhaps most importantly, he worked tirelessly, drawing, painting, and sculpting around the clock and placing everything else in life second to his obsessive and prolific - and constantly evolving - creative ventures. His art was almost always ahead of its time, and his important work spanned approximately seventy years.

Neil Peart might well have been born with an innate inclination toward understanding and creating rhythm, but he also knows a thing or two about hard work. He's certainly been blessed with the brain of a seeker, which has led him to travel the world, geographically and rhythmically, and to remain ever open to fresh inspirations. But, again, his long and staggeringly productive career with his Rush bandmates, bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson, could not be had without keeping the ol' shoulder to the wheel.

"There's no other way to get it," Peart says of the practice and repetitions crucial to breaking new ground. Along those lines, is there another drumming superstar who has so publicly and so aggressively sought to sharpen his or her sticks? Peart has gone to great lengths in his quest for improvement, overhauling his style and his setup in the mid-'90s with the movement guru Freddie Gruber and, much more recently, studying with the embodiment of control and sophistication in jazz and fusion, Peter Erskine. Notice that Peart's teachers tread territory outside Rush's realm of "ornate hard rock," to use Neil's term.

One of the greatest leaps forward in Peart's journey - into the unknown, in fact - has also been made relatively recently. Indeed, rock's reigning king of the sculpted drum part, a man famous for his tenacity in reproducing complex and finely nuanced compositions exactly on stage, has learned to embrace improvisation. (Yes, learned. More on that later.)

All of these endeavors dovetail on Peart's brand-new DVD, Taking Center Stage: A Lifetime of Live Performance. The three-disc, seven-plus-hour video offers an intimate look at every aspect of the drummer's in-concert life, including solo pretour practice sessions (with slowed down demonstrations and PDF transcriptions), onstage soundcheck, and backstage warm-up. The centerpiece of the program is an entire two-set performance on Rush's Time Machine tour, captured at upstate New York's Saratoga Performing Arts Center in July 2010. The live footage, with the camera eye zeroed in on Neil and the sound presented in a drum-heavy mix, is interspersed with conversation about each song with Hudson Music senior drum editor Joe Bergamini, filmed at the stunning Death Valley National Park in California.

The material on Peart's third video - the others are 1996's A Work in Progress and 2005's Anatomy of a Drum Solo - draws from Rush's nearly forty-year career. This includes a song from before Peart even joined the band in 1974 ("Working Man"), the entire 1981 blockbuster Moving Pictures, various greatest hits, cuts from the fiery 2007 album Snakes & Arrows, new numbers "Caravan" and "BU2B" from the upcoming Clockwork Angels, and, of course, a drum solo, this time titled "Mota Perpetuo" (which can be read as "perpetual motion" or "everlasting motorcycle" - or, ever better, both).

It's a challenge to digest such an abundant feast of drumming, but Taking Center Stage does comprise a lifetime of live performance - Neil Peart's lifetime. So it's only fitting that we, the viewers, do some work as well, to chew on the many meaty concepts presented. The sheer volume and variety of Peart's beats and fills is staggering, and, as a testament to Neil's forward-thinking aesthetic, there's essentially no repetition beyond that signature Latin-style ride pattern from the old days (neatly reprised on Snakes & Arrows' "Far Cry"). In the practice room, or when he's writing lyrics and prose travel tales, Peart might strain to push beyond his mortal limits, but here he makes his own perpetual creative motion seem as natural as Picasso saying, "Okay, enough with the Blue Period!"

Did the performance in Saratoga feel different because you were the focus of the cameras?

Fortunately we already used some cameras in the live show, on the rear screen behind us, so it was just a matter of adding a few more and then collecting all that exclusive footage of me. Later that same tour they filmed the whole band in Cleveland and took a whole different approach to lighting the band and the crowd.

The Saratoga one was specifically focused on getting the drums on camera, and then the mixes, as you know, are quite enhanced. Well, I think it's a normal sort of balance - that's about where I hear the drums! We always laugh about that in the studio, because I really do like loud drums. I think they're exciting, and not just because it's me. Yeah, I like that mix. I'll just say it.

There's such a purity of sound, whether it's the rehearsal footage or the performance stuff. The only effects are ones I actually play. I said to the engineer, Sean [McClintock], in these economical words, "It sounds like me playing my drums." That's the highest compliment. If you've done any studio work, especially years ago, it wasn't always like that. When you hear the playback, you go, "My drums don't sound like that!"

It's a beautiful touch to have the interview segments set in Death Valley.

What a difference that made. It was so glorious how it came about, because in the previous two DVDs we had done outdoor "talkie bits," but we'd filmed them at the studio in the Catskills. This time we were filming in January, which limited a lot of the outdoor possibilities. Winter in Quebec I've written about extensively and love so much. But you can't count on getting beautiful days when you pick two days in January. So Death Valley was the perfect place and one of my favorite places on the planet, and it gave us so much variety.

I have to see that I can live with everything over time, of course, but when I faced watching the revised edit of seven hours of myself, that's very daunting. [laughs] But it was necessary to have the playing demonstrations and all that. I don't like watching myself on television or looking at pictures of myself, that mirror sort of thing. I like listening to the music, interestingly. Yeah, that is an interesting distinction - I like reading my writing, and I like listening to our music, but I don't really like watching me. It's the same self-consciousness, I think, that leads to a lot of other behavioral and character sort of things.

The nature shots seemed like a good setting to reflect on your past as well.

Joe Bergamini had been urging me for the past few years to get historic and analytical, which didn't interest me at all. But in this context the overriding theme was live performance, which remains a main focus of my life, and it's not anything that I'm tired of talking about or feel is irrelevant.

So when I looked at the songs as performances ... Like what happened where I just stumbled across that realization about myself - which happens a lot in interviews, and it's one reason I like to do them - the whole theme through the DVD of our songs being made to play live, I'd never thought of that before. It's just the way we naturally worked.

It's so obvious when I look back at "Subdivisions" or any of the Moving Pictures songs, in that they were absolutely made not to be played on the radio, not to be listened to on the floor with headphones, but they were made to be played. Yeah, "made to be played" - that's good! That makes our band so much of what it is, and it's what's sustained us as a live band. Those songs are so exciting for us to play that it makes the show a consistent expression of something real and sincere. I mention in the DVD too that we only play songs we really like playing. And I don't think that's true of all bands. I'll just go out on a limb and say that.

You do hear bands say they have to play a certain song, or else the crowd won't let them out alive.

Yeah, I know. I feel very fortunate. That's a wonderful testament to the band being about playing music that we like: We still like it! Even those songs from twenty, twenty-five years ago, I like playing them. I was saying how a song like "Presto," like a lot of the older songs, feels better to me now than the record did. And Geddy pointed out that our internal clock, our rhythmic foundation, has shifted.

Of course, I've worked really hard on that, and my studies with Freddie Gruber were a big part of changing my whole orientation, not only physically but, I realize now, rhythmically. So I work much more to a rooted bass drum on a figure, and my tempo control is much more based upon the intricacies of the rhythm itself. That's an important part of the legacy of a teacher, because they put you on a path - and this is broadly applicable to teachers of all kinds - and all you have to do is stay on that path and you'll be all right.

I think about my earliest education in reading, for example - being taught to understand a novel, a play, a poem. Well, that ruined, like, Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities, or Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. I can never read those again, because I was forced to dissect them. But it served me for a lifetime.

And my first drum teacher, Don George, same thing. Freddie, same thing. Peter Erskine, a few years back studying with him continues to be part of what I do, because he put me on a path that I can follow forever.

As I get into later life, at fifty-nine, I still don't injure myself, and that's a big part of Freddie's teaching on a physical basis. He's saved me from the injuries that I know have plagued a lot of other drummers, especially hard-hitting ones who are getting older. [laughs]

What's something you worked on with Peter Erskine?

I think Roland makes a drum pad with a metronome that plays two bars of click and then two bars of silence. Well, Peter gave me the assignment to get that little unit and play to two tempos every day, one very slow and one fast. You know how hard it is to keep time at a very slow tempo, but when you're up against the mathematical perfection of a silent click .... I've heard other drummers just have gone crazy: "There's something wrong with that machine!" But what a great exercise. I was improvising in those tempos too, different ones every day, which also served me hugely.

Playing just the hi-hat like that, with no other responsibility but to keep to that tempo, continues to grow in a remarkable way that I feel in live performance now, in terms of time control in the tiniest increments, and of accuracy - getting to truly feel when it's right or wrong, and be right! How many drummers think they're playing the right tempo and they're playing too fast?

Years of working with click tracks and metronomes helped, but they had a downside, and I found that in the mid-'90s I started to feel very rigid and mechanical - accurate, yes, but not the kind of accuracy I wanted. It made me want to study with Freddie. Having found Freddie and worked with Peter Erskine has served to let me be accurate and feel good inside, without feeling constricted and rigid. Yet my understanding of time and my control of it is way deeper than it ever was when I could do a mathematical, drum machine kind of accuracy.

Where does improvisation come in?

Investigating improvisation has made me more resourceful, by necessity. That's such a great parallel with traveling. In my writing over the years I've done many comparisons between drumming and traveling and improvising and traveling. It's all about adapting. I love the fact that when I start improvising figures in the solo, I adapt to each one. That's how you keep going. You go, Okay, that happened, so then this will happen, trying to keep yourself out of repeating.

Improvising has helped me enormously in improvising out of trouble. That's an interesting insight right there. If you're wedded to a carefully arranged part, any, oh, mechanical problem that comes up to distract you or any loss of concentration means that an unrolling program gets interrupted. But when you're improvising there's none of that. Everything that happens is by nature and by intention unexpected, so it does prepare you to deal with the unexpected better. I noticed that on this last tour I was much more able to handle an error, whether it was mine or somebody else's or a technological thing.

In the band's case, we just wanted to introduce more improvisation. We do like to arrange things, and we love to re-create recorded songs as well as we can do live, but on this tour particularly all of us were interested in getting outside and more interested in jamming. And as we get back to work on new material right now, we're talking in those terms. We collected a whole bunch of soundcheck jams, just like we used to do twenty-five years ago. Alex went through some of the ones he thinks are the most interesting, and he's encouraging us to use them as the basis of compositions. And the thing we've been doing live too, on the very last song of the show, "Working Man," is we just go. It's truly a jam session, in the time-honored way that I always did it as a kid and you probably did too: You get a cue. "When the guitar player plays this figure twice, we all come out." We're all inspired by that, and we're saying, "We're doing this in the studio." It's so exciting after all these years that we have these feels that inspire us, and the next record is not a question of "What are we gonna do this time?" It's like, "Look at all the stuff we're gonna do this time!"

On the DVD, "Working Man" stands out as pretty much the lone example of straight-up 4/4 bashing.

Yeah, and it's one where Geddy and I are much more of the traditional rhythm section, playing the supporting role for a soloist who's going to the moon. Alex just goes completely out there. We talk about it later and he says, "I don't even know what I was doing there!" That's the kind of person he always has been - he's very spontaneous, out of the three of us.

So yeah, that's a neat role for us because we don't do it all the time. We figure it's free rein. We've always joked that when vocals are going on you're very respectful as an accompanist, but not when it's a guitar solo. [laughs]

Do you ever think about the words and meaning behind the songs while you're on stage?

Sure, I do, especially when I see them reflected in other people's faces and see them singing along. An obvious example but a very good one is "Limelight." That so much reflects on live performance and "living on the lighted stage" and the sense of unreality. It remains just as true now as then. "Approaches the unreal." Yeah - how many times have those words been reflected back at me from an audience singing along? It's a feedback loop of my own reflection on the experience, and it's still true, so that's kind of cool.

I've heard musicians comment on that unreality. Carlos Santana said something about how you're fawned over on tour but then you go home and have to take out the garbage, which is an important but often difficult transition.

Oh, yeah. And that's one thing I must say: I love traveling by motorcycle on tour because I come down to the everyday every day. I go to gas stations and eat in diners and travel through traffic. What could be more gritty, down-to-earth real than fighting through traffic every day? And I have roadside conversations with strangers or at a gas station or motel that are really lovely little exchanges, just human to human.

It's certainly true what Carlos was talking about, that dichotomy. Lift your finger and something's done for you. Then, when you get home, somebody else's finger is pointing at you, telling you what to do. I value that too, very highly. I love being at home, and I love doing the grocery shopping and the cooking and all that. But I've been able to keep touring fresh but also nourishing in the human sense. Every single day I feel a part of human life; I never feel as if I'm in a bubble. My life is so real on the road, much more so than it used to be, and it really helps me to keep my balance.

I think of Pink Floyd, and Roger Waters' famous essays on alienation in Wish You Were Here and The Wall, and I know what that feels like. I wrote to him years ago when I heard about the Wall performance in Berlin and just expressed the fact that it had been my autobiography as well. But you can't survive with those kinds of feelings. He had to change his feelings; I had to change my environment over the years. So between bicycling and motorcycling, it keeps me out of that bubble and keeps me engaged with real life. Gives me something to write about too. God, regular touring life - I'd have no stories! What an appalling thought. I never thought of that before, but that's one of the worst prices.

Caress Of Steel

You have a distinctive touch on the drums. On the DVD you explain your reasoning behind hitting as hard as you can. There's conviction behind every note, real clarity. Could some of that stem from working things out very precisely beforehand?

The conviction you describe was the confidence of: I really know this part now. I think of, just for example, "Tom Sawyer." I would've played that dozens and dozens of times and developed all those little figures to memory, such that they were played as a performance. There was an absolute knowledge of what I was doing and why, which would come through in that level of clarity and conviction.

You also said something in one of your previous MD interviews along the lines of how indecision can lead to mistakes. What you're talking about now is essentially a lack of indecision.

[laughs] Absolutely so, yeah. That's the way I worked thirty years ago, and it has evolved over time. I love the fact that now I can approach that kind of conviction even when I'm makin' it up. It's true that I've become more confident about improvisation. I don't think it's well understood that it's something you can learn. I didn't know that. Anatomy of a Drum Solo was the perfect turning point, because I announced in that DVD that I am a compositional drummer. And then almost immediately I started thinking about that and going, Wait a minute. Why limit myself? I want to be improvisational. So I really did set out to learn how.

It's very interesting how I've built the confidence that I used to get from rehearsal. Studying how improvising works, and especially how my mind works when it's improvising, has served to give me the confidence where I can be much more free. The two newest songs, "Caravan" and "BU2B," were recorded that way - much less prepared, and consequently much less orchestrated than in the past, but certainly with no less power and conviction. I trust myself more now - that's what it is! A lot of good experience where I've managed to do it night after night for eighty-one shows just on this tour gives me the confidence that I'll be able to do it.

So realizing that you're a compositional drummer made you want to become an improvising drummer. What if it's the opposite, if you're a drummer who isn't comfortable committing to specific parts but you'd like to learn to be more compositional?

Very interesting, and so likely to be true. I've talked to other drummers a little bit about that, about ones that can't play the same way twice, but there's more to be learned there. I've known guys like that, that just play great all the time. But you have to play so much safer then, generally.

There are a lot of reasons why I get away with being so active, especially how I got away with it in those days, and it was because of having carefully orchestrated drum parts that framed the necessary vocal parts of the song. I never got intrusive in that respect. And I know what the lyrics are and where the vocals are going to go. I don't know how many drummers I've talked to that had to record a song when the lyrics weren't written yet, and what a terrible handicap that is.

I love the fact that not only are the lyrics written, but because I wrote them I know them. [laughs] I know where I can punch up vocal rhythms and accents, for example. It's really lovely to be able to do that. I think a lot of drummers are forced to play simpler than they'd like to, just not to take a chance on being in the way. It's like a session musician thing-you're supposed to be invisible. But in a band you're supposed to express yourself.

As far as the repeatability factor, that's something I don't know enough to comment about, but I'm interested in it. I know there are drummers like that, and the fact that they might want to be more compositional doesn't surprise me.

You really do get away with being more active than most drummers, and it's certainly not an accident.

No. Absolutely by design, and that's something the three of us shared, again, from the outset: We really wanted to play, and we really wanted to play better. That kind of curiosity and willingness to experiment took us on some strange journeys, but it's served us well in the end and made us happy to this day.

We've done little things on our own. I love big band music and look forward to playing it, and I do things for my own amusement, maybe with hand percussion or melodic percussion. But for the most part - no, for the absolute maximum part - I'm completely fulfilled as a drummer by what I get to do in this band. And as a writer I love being the lyricist too.

You have some pretty special bandmates as well.

Yeah. I like them. Don't tell them. [laughs]

Replay

During the refinement period where you're learning a song and creating the drum part, you're playing along to a demo made by Geddy and Alex, I assume.

Right, yeah.

Do you record yourself playing everything from the more straightforward to the more experimental?

Ah! Good point. No, I don't record everything. I experiment with the kinds of ideas that might work - finding good rhythmic patterns for verses and choruses, and working on transitions and all those things. If a part needs to edge forward and be propulsive a little bit, you learn to give it that feel; if a chorus needs to lay back a bit and feel more relaxed, you learn to do that. At a certain point I want to hear it, and that's usually after I've played it for a few days. So that's when I'll record it.

To record everything is too much information. And honestly, what I'm doing early on doesn't need to be recorded. I think this is important too: If you like it, you'll remember it. I'm one for jotting down notes from time to time, but I really don't have to. I don't recall ever saying, "Gee, I wish I'd taped that." There's a certain self-editing process that goes on in the early stages of a song that's absolutely reliable. If I think of a little phrase, like the title of a song, and smile, I'm going to remember that. If I play a little phrase on the drums and smile, I'm going to remember that. That's a good barometer-the smile factor.

How has the process changed from the days when you were all together in the same room hammering out a song? I guess that's exactly the difference - that you're not all playing at once.

Yeah, so much better. It wouldn't necessarily work for a band at the beginning, and of course I'm glad we did all that. But it was very slow going. Trying to sort out and learn your part and trying to adapt to the others when they're doing the same thing was so inefficient. And I bet a lot of good things get lost, because if you're trying to play for the other guys too, you're not going to go out on a limb too far, because then you're sort of sabotaging them. Whereas when it's just me playing along with the demo, there are no consequences. And there's no responsibility. That's the other word. I often talk about consequences in terms of improvising, but there's a perfect example - there's no responsibility to hold the band together.

Even in a rehearsing context, as a drummer it is part of your job. You always want to give the other guys that foundation. Well, on your own you can try out many more ideas in a much shorter period of time and take more chances and have the opportunity to refine an idea that may seem a little bizarre if you just played it for the other guys.

And I have to say my parts are way more intricate and daring now than they ever were in those days, if I think back to the Permanent Waves/Moving Pictures era. I can hear that I was focused on foundations and supporting the band. Whereas later, with my drum part on a song like "Bravado," for example, where it gets increasingly active and then sinks down dynamically and is very carefully constructed as a sensitive part of the song, I wouldn't have had the luxury in those days of refining something to that degree. Or something like the second chorus of "Leave That Thing Alone," where instead of playing time I play a Nigerian drum ensemble. That wouldn't have worked in the old way of doing things.

Or the fill in "Caravan" that I talk about on the DVD, where our coproducer, Booujze [Nick Raskulinecz], kind of air-drummed that part to me and I had to figure out how to play it. The figure and the triplet feel of it need a flamacue kind of sticking that I had to spend quite some time on, figuring out how to do it and then how to do it well. Those are two things: First I had to figure out how to do it, and then I spent more time refining it to do it well.

And that can take a while. Maybe not for you, but ...

No, I don't mind saying it did. And that's why I never mind telling people, look, our complicated songs take me three days to learn. I don't just sit down and play like that. I think it's important for people to realize that, and I never try to come off like some kind of a superhero. Nor the self-deprecatory kind of, "Aw, it ain't nothin'..." Yeah, it's something - it took me years! But I don't mind saying that it did take me years.

Traveling Music

It could be simplistic to make too direct a connection between your travel experiences and specific drumming figures, but your roster of fills and rhythms is vast, and it's not stuff that can be acquired by just sitting with your drums in a room.

No, that takes years ... and wheels. Oh, that's good-years and wheels. [laughs] But yeah, of course I learned a lot from West African music, from a distance. Some things from recordings, like King Sunny Ade from Nigeria. But a lot of it was hearing drummers play in Togo or Cameroon or Ghana. Ghana is probably the nucleus of the drum for the whole planet, I might venture to say. Those kinds of experiences are unforgettable. Or China - the chanting in the temples.

Here's a beautiful cross-cultural rhythm: just 1, 2, 3, rest; 1,2,3, rest ... I've heard that rhythm riding my bicycle beside a church in Ghana, behind the choir singing. It'll be on a bell or a block: bum, bum, bum ... bum, bum, bum ... In Chinese temples, when they're chanting, I'll hear that exact same pattern, maybe on a metal disc this time, or on a temple block. And I ran into it in Western music somewhere, just by chance the other day, and I was thinking that of all the rhythms of the world, that might be the most prevalent. That simple little thing of three beats and a rest, because it's recognizably a repeating rhythm, but it's stripped down to its very essence. It's the [sings rhythmically] simp-lest syn-co-pa-tion, to leave one out. If you look at the book of syncopation, I bet that's page one.

Freewill

One last question about playing live. Each member of the band fires his own sequences here and there during the show, so I was wondering: Do you get tempos for each song in your in-ear monitors?

No way. I object to that. First, [in drum rehearsals] I play along with the recorded versions, so click tracks and sequencers are inherent. During band rehearsals I use a metronome with two lights that flash alternately. That gives me enough information at a glance to keep me and thus the whole band on track. But no, starting with the final production rehearsals I put aside that crutch and just do it live. Very satisfying.

In the old days, in one film we used a click track behind it, and I was always terrified that it wasn't going to work. So this obviates that. I'd rather take freedom and responsibility in that sense than have something to rely on, because I can't trust that. There's a very important little metaphor going on behind all this. Yeah, freedom and responsibility are much more preferable to me than reliance on a machine.

Neil's Setup

Drums: DW Collector's series in custom steampunk finish

A. 6 1/2 x 14 snare (straight VLT shell)

B. 3 1/2 x 13 snare (straight VLT shell)

C. 7 x 8 tom (VLT shell with 6-ply rings)

D. 7 x l0 tom (VLT shell with 6-ply rings)

E. 8 x 12 tom (VLT shell with 6-ply rings)

F. 9 x 13 tom (VLT shell with 3-ply rings)

G. 12 x 15 floor tom (VLT shell with 3-ply rings)

H. 16 x 16 floortom (X-Shell with 3-ply rings)

I. 16 x 18 suspended floor tom (X-Shell with 3-ply rings)

J. 16 x 23 bass drum (X-Shell with 3-ply rings)

K. 13 x 15 floor tom (X-Shell with 3-ply rings)

Not shown: 6 1/2 x 14 Edge snare

Heads: Remo Ambassador X snare batters and Remo/DW Coated/Clear 2-ply tom and bass drum batters.

Hardware: DW, including 9000 series copper-plated stands, 9000 series double bass pedals, and 5000 series hi-hat stand

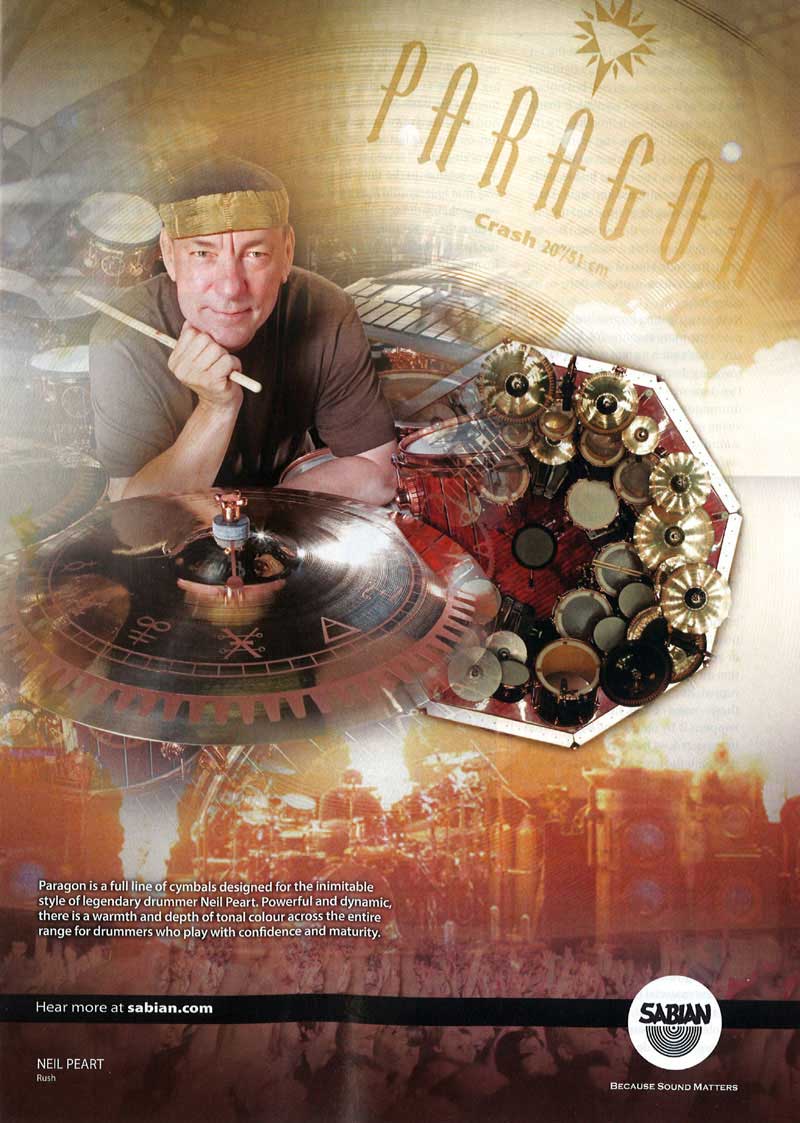

Cymbals: Sabian Paragon series (except auxiliary hi-hats) in brilliant finish with custom steampunk design

1. 10" splash

2. 20" Signature crash

3. 14" hi-hats

4. 16" crash

5. 22" ride

6. 14" Vault Artisan hi-hats (auxiliary) with 8" splash above

7. 18" crash

8. 20" Chinese with 20" Diamondback Chinese above

9. 19" Chinese

Electronics: Roland TD-20X percussion modules, V-Drums pads mounted in DW shells, V-Cymbals, V-Hi-Hat, and XV-5080 samplers; Kelly SHU internal bass drum mic; Alternate Mode MalletKAT Express and FatKAT trigger pedals; Dauz trigger pad; Glyph hard drives; Monster power conditioner; Behringer line mixer

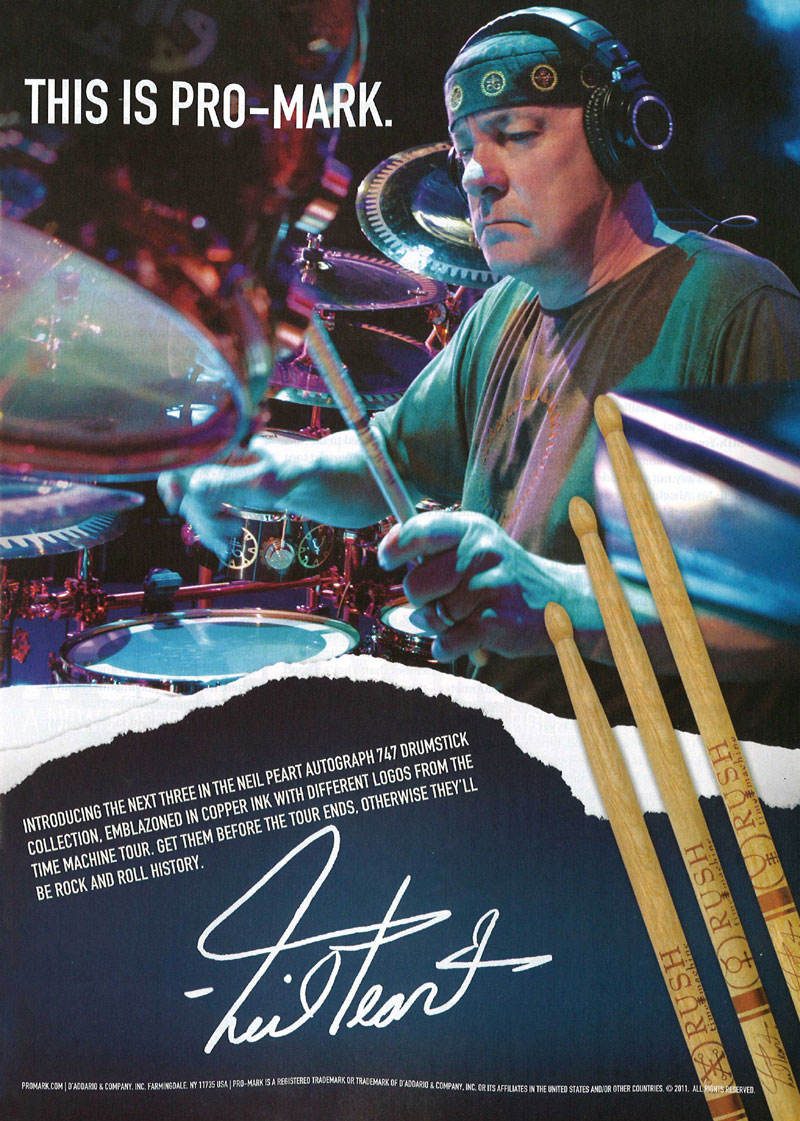

Sticks: Pro-Mark Neil Peart signature 747 model