Classic Rock Presents: RUSH Clockwork Angels

Classic Rock Special Edition, June 11, 2012, transcribed by John Patuto

CONTENTS

- Welcome

- Q&A: Neil Peart

- Track By Track: Geddy Lee Guides Us Through the New Album

- Working Them Angels: We Meet Producer Nick Raskulinecz

- Q&A: Geddy Lee

- Sealed With A Kiss: Gene Simmons on Touring with Rush

- Afterimage: Rush Remember Their Friend and Photographer Andrew MacNaughtan

- Q&A: Alex Lifeson

- Moving Pictures: We Meet the Team Behind Beyond The Lighted Stage

- Machine Heads: The Men of Rush Talk Instruments and Gear

- Starmaker: Hugh Syme on 30 Years as Rush's Art Director

- Archive: An In-depth Tour of Rush's Epic Back Catalogue

- Farewell by Geddy Lee

WELCOME

I know all about the concept of the fan pack, and for me there's no band more worthy of one than Rush. They inspire real fanaticism and you can definitely count me as a fan; I know all of their stuff!

When I was young I loved Neil Peart and worshipped him. I have a big moustache right now, actually. Maybe it's a subconscious tribute to Neil in his kimono days!

I watched the Exit Stage Lift video millions of times when I was first getting into playing the drums. In fact, I used to play La Villa Strangiato when I was about twelve; to be honest, my version wasn't that good. I hope I did a better job when I performed YYZ with Geddy and Alex onstage in Toronto in 2008. That was an awesome moment, though I know that without Neil it wasn't even fucking close! But if Rush hadn't existed, then I wouldn't have been the drummer I am today. I'd have had less licks to steal from Neil.

Soundgarden, Jane's Addiction and the Foo Fighters would not have sounded the same without Rush. And I know for a fact that Dave Grohl loves Alex's guitar playing. That Foo Fighters song Rope - I mean, come on! That's the hugest Rush influence right there!

I've been lucky enough to hang with the guys and it's magical because I used to idolise them so much, but even more special because they're such great people.

Enjoy your fan pack. I know I will!

TAYLOR HAWKINS

Q&A: NEIL PEART

By Philip Wilding

YOU MIGHT THINK HE NEVER CRACKS A SMILE, BUT RUSH'S DRUMMER IS MORE THANK HAPPY TO TALK ABOUT MODERN ALCHEMY, THINKING BIG AND WHY HE'S NEVER GOING TO WATCH BEYOND THE LIGHTED STAGE. BUT FIRST HE'D LIKE YOU TO TRY THE SOUP...

The hilly residential enclave of California's Topanga Canyon attracts a certain crowd best described as 'well-heeled bohemian'. It's been pulling in the great and the good for years: Neil Young used to live here, as did Marvin Gaye; Stephen Stills too. Taylor Hawkins lives somewhere over the hill. Nancy Wilson is a few miles down the road, and some of the guys from Tool have homes here too.

That said, The Inn Of The Seventh Ray is still something of an eye-opener. The restaurant's generous patio looks out over a small babbling brook, while the speakers overhead play an extraordinary mixture of pan pipes and soothing new age tunes; a particularly 'unique' interpretation of Greensleeves makes us look up sharply from our raw soup. Soup, the menu informs us, that's been 'created through the vibrations of each day'.

Neil Peart's impish grin tells you two things; that he loves this place, and that he's very much enjoying the bemused look on Classic Rock's face. He's just driven up here from his home after a morning workout at the gym and pool in preparation for Rush's next North American tour, which is still some months away. Like the boy scouts, Peart's always prepared. This is the man, after all, who plays drums for an hour to warm up before he goes on stage. As Geddy Lee says: "He drums to drum."

Peart pulls back a chair and peruses the menu. There's that grin again. "I thought we could do a yoga session instead of the interview."

This place is incredible...

Isn't this good? I'm so glad I thought of it, because you have to take a minute some times. You and I have to do this thing, but I was thinking, what's the best possible way we can do it? It's how I live when we're travelling on the road: if I have a day off, what's the best possible thing that I can do? Can I go to the Grand Canyon? Can I go to a national park? Can I go to the desert? And today was no different, given that I want to talk to you and you want to talk to me for various reasons, but if we have to do that, then why not make it something cool? I love it here.

Let's talk about the new album. It's so full of life, and you improvised a lot of your parts this time, which is a first.

There was so much improvisation, and that makes it all the edgier. As I wrote in my little essay about it for the band biography, I think the listener can feel that. It's like listening to The Who's Live At Leeds; you can feel the band on the edge between total control and total chaos. You only do that kind of performance once; the spontaneity makes it so fresh and thrilling.

A lot of it came from the new freedom you found improvising on this last tour, didn't it?

Yep. All of us in our various solo spots were pushing it and going out there, and it was phenomenal for each of us to share. All unknowing, I started that a few years ago when I studied with Peter Erskine (Weather Report, Steely Dan, Kate Bush); part of what he taught me was with the metronome and hi-hat only, and I came out of that with such a sense of time. I can listen to two things now, and go somewhere really far outside and still draw back and drop in, so there's so much more stuff that I can get away with.I do that on stage now. On that last tour, I found for the first time that if someone makes a mistake and gets out of time I can hear what's happening and what ought to be happening at the same time. I can step back and see what we need to do until we're tight again. I can figure it out and smooth over those train wrecks. In the forty-five years I've been playing, this is a whole new plateau.

Both Ged and Alex have commented on what Nick as a producer has brought to the band, but it sounds as if the work he's done with you has been especially important.

He goofs around, but the enthusiasm and the energy is fantastic. The first time we worked he'd ask me to play something, and would mimic it and sing the parts, and it would be so over the top, just extraordinary, I'd be ashamed to throw a fill like that in myself. But I'd be like, okay and then I'd pull it off and he'd be, 'That's great!' It's like the Caravan drum fill that I laid out, we went back into the booth to listen and Ged looked over his glasses at me and said, 'Oh, he wants to make you famous.'

This time, it was more immediate. He was in the room with me, not listening to playbacks - he was right there, so that every time we stopped, we'd be conversing over the parts. He was playing along with me, I didn't have to learn the arrangements. He's a generation younger than us too, and that's kind of an important touchstone. We did Snakes & Arrows with him and wanted him back, and he wanted to be back. He's the perfect catalyst, that's the word; he's more than a collaborator...

He brings out the best in you?

I don't know how people work without that sort of honest input that Nick gives us. I remember Stewart Copeland asked me one time about how we work and why we have a co-producer; he couldn't understand the dynamic. It was not the way The Police got things done, but talk about a band that was driven from the beginning by divisions - we've stayed so close, oh, they were so drawn apart and then they had to select a co-producer who was almost a moderator to placate things in the studio. Stewart's memoir, have you read it? It's called Strange Things Happen - it's really good, I highly recommend it. The stories he can tell...

I was telling him a story about the three of us, about a song we were working on, and he said, 'You guys talk to each other like that?' Reasonably, you know? And he came to see us at the Vegas MGM Grand and came in during the intermission and I said, 'You must have played here: and he said, 'Yeah, a couple of times.' And he said, There's a piece of someone's ear over there; I think I kicked Sting over there.' I understand what some bands can be like. I'm not judging. But how awful. It was funny to me, that just my describing a conversation that Alex, Geddy and I had about our future plans was of total disbelief to him. He couldn't believe that a band could be like that.

It's a very modern sounding record, but you're not afraid to give a nod to the past.

What was it that Oscar Wilde said? 'Self-plagiarism is style.' We certainly do a few tongue-in-cheek nods to Bastille Day on Headlong Flight, that's deliberate.

In the essay you've written for the album you say that these songs, "tell a story set in an alternate timeline, with alchemy, clockwork, and steampunkery." And it also addresses the Meaning of Life. You don't like making things easy for yourself, do you?

I know, I can't help it. The starting point was the steampunk idea. I was aware of it as a reader. My good friend Kevin Anderson - who has done the novelisation of this album - he's so prolific and so skilful, and he was one of the pioneers of the style, for sure. I love how it's a direct counterpoint to cyberpunk, it's like a different vision of the future.

So I was enthralled by that theme, and my character's journey through this world. I also had in mind Voltaire's Candide too, that was a germ of it. Plus, there was so much stuff I'd been reading about the circus stuff, the carnies, from Robertson Davies' novels, and I'd read a lot of history from the south western part of the US, geographically - the most interesting and the most beautiful, too - and that figured into the story of the explorer Coronado who kept going out into the desert to find the fabled cities of gold, but could never quite get there.

And The Wreckers was actually from Daphne Du Maurier, even though they were real. Some would just wait for a ship to wreck and plunder it, but others would set up lights to deliberately draw the ships in so they would wreck. That's been in my mind for thirty years, since I read that story - I guess it's an episode in Jamaica Inn. So all of that coalesced into the character and the history of the story, the whole concept.

Headlong Flight was partly inspired by the death last year of your friend and drum teacher, Freddie Gruber.

Freddie gave me the line in that song, 'I wish I could do it all again'. Because there he is: 84, he grew up in New York in the 40s, worked out through Chicago and Vegas in the 50s, LA in the 60s, and since then his path has crossed with everybody. And his response to it all was: 'I've had quite a ride, I wish I could do it all again.' I don't feel that way. Maybe I will when I'm older. Nevertheless, I respected it so much, and what a great thing for my character to reflect upon.

And anyone who's subject to depression or has suffered grief knows that even sunny days can look dark, right? So that little couplet occurred to me, 'Some days were dark, some nights were bright, I wish I could live it all again'. It worked perfectly for my character, but it's obviously a tribute to Freddie too. I love that I could make it personal as well as universal.

You said that The Anarchist was partly inspired by Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent.

In part. That's where that character comes from, there and Michael Ondaatje's In The Skin Of A Lion. He has a central character who's a committed terrorist/anarchist. Anarchy is an innocent utopian thing for him, an ideal.

But Wish Them Well is more personal, yes?

I have a very large circle of friends, really close friends, and once a year or so I lose one of those. And it's either a succession of unfriendly acts against me, or some betrayal, which is unforgiveable, you know? They're sad in a way, but you have to remove them from your life. I don't hate them, I won't bear a grudge, but you can't be a part of me anymore. So, that sentiment, Geddy really responded to it as well. It's a really humane way to be: 'I don't want to be around people like you, but I wish you well'.

How hard was it to get the whole idea of making a concept album started?

It's funny...It started with Geddy's suggestion that we make a compilation of all our instrumentals and write a new one to go with it, perhaps something more extended, and that was the trigger for me. Then I got thinking...I was all hyped on the steampunk aesthetic at the time, you know? What if we went long, and developed it? To paraphrase Caravan, I couldn't stop thinking big, really.

Was there a point where it all came together, or was it more a case that it evolved?

'Process' is probably the right word. I had three titles for chapters: Caravan, Carnival and Caravel. I was going to have them convey the journey, and they all evolved into a much more developed story.

It's a bold undertaking.

We know, it is bold. But we couldn't not do it, once it started to come together. It evolved so beautifully; a few songs came together and then we went out on tour. We couldn't help ourselves, we even used the stage set we'd built for Clockwork Angels.

You've created a whole other world for the album...How much more will that be developed in the novelisation of the record that Kevin Anderson's working on with you?

The one thing I've learnt from Kevin is that it can be as wild as possible in terms of imagining, but people have to do what people would do. It has to be logically consistent, and Kevin and I have been much more involved in the world building for the novel. Clockwork Angels the novel is very much the notes version, the lyrics are the footnotes.

You and Kevin go back years...

He sent me his novel, Resurrection, Inc., around the late 80s, and it sat around for years, with a big lurid skull sci-fi cover. But when I finally did read it, I was blown away, because it was a novel of ideas. I went to visit him up in Northern California and we got together pretty much every time I came through. From the beginning we talked about making a project together; he had a novel planned and he wanted us to do an album in tandem way back then, but that never worked out timing-wise and mood-wise and whatever. So, as soon as I saw this coming together, I thought, here's the perfect opportunity.

There's a narrative to the album - a young man's quest across a world of steampunk and alchemy. I'm paraphrasing, obviously, but it's almost deliberately vague in parts. Will the book fill in the gaps?

We did want to leave a bit of mystery to all of it. The book will come out in time for the tour, so people have a few months to dream up that world for themselves. I'm consulting with Kevin all the way along and he's constructing the novel to follow the pattern of the album. But we had to come up with so much else in terms of the world and the characters.

Whittling it all down sounds like a tough undertaking.

It was very difficult, because I wrote reams of lyrics as I had a big story to tell, and then Geddy chiselled it down. He'll have a song that he and Al have constructed and they make it fit, so adjectives go flying out of the window, imagery goes, so it becomes very concise in terms of action and portrayal, which I don't mind. But I worked so hard, syllable by syllable, to get maximum value...

It feels very distilled, very direct.

Exactly. Distil and compress. There's a lot under the skin, that's to the needs of the music, and we were determined not to be archaic. Some of the shipwreck adventures, the seafaring language that I'd come up with, was deemed not suitable for the streamlined model we were pursuing.

So it all adds to the immediacy of the album?

It's the spontaneity and the craft. I guess the songs started just as jams, and Ged was really responsible for that part of things, sifting and then stitching things together, and then the two of us bringing up the lyrics and hammering - that is the word I'm looking for - and then distilling them down into that fine essence. I wrote little prose interludes between songs to try and clarify the action, some interstitial tissue to join it all together a little bit, which ultimately the book will do, so that's fine. So I made them very minimal, just to give them some colour. I like to give people a hint, if they care. When I was a kid, I never listened to lyrics...

That's like hearing that Quentin Tarantino doesn't watch violent movies!

Ha! But it's perfectly legitimate not to listen to the lyrics - you just sense they're good, care has been taken here, you know. That's what I always think about drumming: people don't have to know about the technique of drumming or song-writing or arranging, but they can sense that care has been taken, that's the content we receive in certain quarters. 'Can't you see? We're trying hard here...'

You've introduced alchemy into the story: the 'u' in Rush on the cover is the alchemic sign for amalgamation, right?

That's right. I was just fascinated by the alchemic elements, because they're beautiful. I came across them in the Diane Ackerman's book, An Alchemy Of Mind, a beautiful book in every other way, and I happened to notice that design, and I got curious. What are they? Where are they from? It goes back to Egyptian times and was considered science. It's still practiced in a cultish sort of way; in fact, there was a symbol for silicone that said 'for modern alchemy only'. Now think about those words: boom! 'Modern alchemy' - what?!

And those alchemic elements are repeated on the album cover too.

It's enigmatic. It's one of those things, even in the artwork, we're never going to show the angels. They're going to remain imaginary. Even in the novel we never describe them too much, just to say that they are larger than life and clockwork and hydraulic. There are sounds in the mix, there are all these backward echoes: to me, that evokes the great wings, these figures of such majesty. And then I was thinking, too, of the circle of where you are in your life and what you're learning about and what you're preoccupied with, where you are on your journey.

Also, I love the alchemic idea of the quintessence, that it's the fifth essence, some kind of dark energy; it's so intriguing. And the philosopher's stone [believed by some to be able to turn base metal into gold and silver], the square inside a triangle inside a circle, it means squaring the circle. It's fascinating stuff. You don't have to believe any of it. Fairy tales and religion are fascinating if you don't believe them.

Talking of the journey, you turn 60 this year: how does that feel?

I feel proud as hell. I'm at the height of my powers in one sense, but also I can't help feeling the empathy for someone like Keith Moon; he never got to be 59. Dennis Wilson neither. John Bonham...These are cautionary tales in a sense, but they break my heart: they had children, they had loved ones, they never got there, they never got this.

This?

This. Our career. By good luck and design, we take the trouble; I'm already in training for the tour in September, I'm physically training now, and in June I'll start the first rehearsals, and then in July we'll rehearse as a band for close to two months, because there's so much new material to develop. So for a tour starting in September, I'm already working on it now.

Do you get glimpses of your younger self when you play the older material? You said as much the first time you went out did 2112 in its entirety.

When I'm relearning the material to tour and I'm playing along with those parts, I'm always in touch with that. We're about to be given the Governor General's Award and they've made a film of us for it, juxtaposing our band with a band of 17 year old aspiring progressive musicians. We've just filmed our part of it, and I was able to say that I very much keep in touch with my inner 17 year old and I'll check in with him about a decision sometimes: 'do you think that's cool?', or 'do you think that's alright?' I had a very strong sense of right and wrong at that age, and a lot of it was good: a sense of the purity of music, that I'll do a lot of things for money but not music. I accepted being semi-pro all those years because I could make a living other ways, but other musicians I knew back then would make that their guiding principle, so they'd play polkas and country. And I just said no...

There are a lot of people who would pay good money to watch you playa polka.

I could do it too. I'm always glad that when I listen to the early songs and the lyrics and all of that, yeah, maybe the craft is lacking, but the spirit was true. I might have had more energy than control then, and I was aspiring to what I have now - the kind of technique and control - but that's what I was trying to do, even back then. I've mastered what I was aiming for thirty years ago. I hear it in there, all this ambition, all this energy, but without the deeper understanding of time that we as a band have now. There are some dirty grooves on this record, stuff I wanted to do thirty years ago but I would approximate it; now I can deliver it, pull way back on the time and dig in deep, Booujzhe [producer Nick Raskulinecz] in front of me conducting, and it's delivered with the most sublime technique. That's what I love.

You can hear all those years of work in this album; the title track is as good as anything you've ever done.

It really is. I hope it's in the live show forever. That song, too, is the oldest piece of music. Alex gave us a little demo way back before we started writing, and right away I pointed at that one and said, 'We've never done anything with that kind of feel: As a drummer I wanted that, it was so good and I wanted so much to play it. It's so unusual for us, but it still has all the intricacies and techniques and the challenge and, obviously, the performance.

And so much melody too, it's a really pleasant surprise.

Listen to The Wreckers. When Ged and Al came out with that, they were really pleased that they'd written a Barenaked Ladies song! That was how they told it. It's so melodic and straightforward, but it's so great to shake it up like that. We weren't afraid to do that.

You were saying earlier that on the last tour the band didn't hit their stride until twenty shows in.

It's true, those first nineteen shows were interesting in their way: they were edgy, and we were all decently well rehearsed, so it's never going to be a disaster. Even though we always think it will.

Do you?

Oh yeah. All that can go wrong will go wrong, every night going on that stage. But it's like the old jazz thing: there are no mistakes, only new parts.

You played solo on The Late Show With David Letterman last summer, how was that?

I only found out a week before, that I had to cut the solo down. I just thought they wanted me to come on and play. It's like eight and a half minutes, that's not too long, you can get that between commercials. But that wasn't what they had in mind at all. So suddenly I'm frantically, manically editing, and we're on tour, just two days before we started on the next leg. So I flew from Los Angeles to New York to do it, and then on to Charlotte for the next show. They had to hire a truck with two drivers, because my kit had to go straight from that show to the next, so they needed these drivers going non-stop to get there in time. And when I said I'd do it, I said I wanted to use my kit with the rotating riser and my screens to light up like they do on stage.

It was complicated, but...

Did you enjoy it though?

Let's just say it was hard work. I had to think of all the ways I could compress the eight and a half minutes, or whatever it is, down to three minutes and something. So I had it in my head, an arrangement of my whole solo...It was too much! [Laughs]

At this stage of your career do you feel like you're in the second act, or has it been more of a continuum?

It's more of a continuum. I love the sense of moving forward that we've built as a band, and in my life personally. The recognition aspect has been grudging, but steadily given over, and receiving the highest honour in your own country is lovely. It's for being good citizens, that's the way I see it, being proud citizens, and citizens of which the country is proud. It's complicated syntax, but you know what I mean.

We know that we've conducted ourselves, as artists and musicians, flawlessly. Nobody's perfect, but when you have the chance to make a decision, you can make perfect decisions. It's a consensus: if the three of us all agree on something with pure motives, then there's nothing to ever feel ashamed of. We never had a disco period, you know?

So there are no regrets, in the truest sense. And also, I hope someone who likes us, our music, or admires us as people can feel that we would never let them down.

The last time we spoke, you still hadn't watched Beyond The Lighted Stage. Has that changed?

I probably won't ever watch it, no. I'm really not interested in it. I like reading my stories over, I listen to our music from time to time, but I never watch DVDs. I don't look at myself, I'm not that kind of narcissist, and also I know everything about it. My parents have seen it, and everybody's told me everything about it, and I'm glad they got that dinner with the three of us, that dinner was incredible...

The scene where you're all eating together - and the further footage of that meal that's on the DVD - showed your true identity, that the band have real heart.

I agree, I know. I'm glad people saw that because it's real - these three guys have been together all this time, but its warm and friendly as can be. Because we're close, we balance each other. No-one gets away with any of that shit, that's the difference.

When bands start to separate, then each wedge can do whatever it wants, and no one can say anything. If you're going to stay friends then you're going to say something if someone's out of line in anyway and we've kept egos in check all the way because of that. Once you're separated, you can get an elevated opinion of yourself, but you can't be friends and get away with doing that. It's impossible. If you're going to be close then you have to stay level.

You once said that your motorcycle is freedom. What did you mean?

It feeds my desires, in a very true sense. I love mystery. If I'm out walking in the woods and I see a path, then I want to know what's on that path, you know? Roads are just the largest extrapolation of that. If I'm out snowshoeing or cross country skiing and I see another possible route or animal tracks going somewhere, then I want to follow them and I want to know what's over that hill. I started skiing when we first worked in Quebec in 1979, doing Permanent Waves, and I got so entranced by it, and by winter. And because of that, I go every year as long as I can, sometimes as long as a month, and I ski or snowshoe every day.

And what great conditioning it is! But also I love the woods, I love the adventure of getting off the beaten path, the road less travelled, you know? The motorcycle is no clichéd 'easy rider' sort of thing, it's where can it take me...I look at that map, and every day there's somewhere new I can be. We've already got our itinerary for the fall, and I'm looking at the days off and I just think, look at the places I can go!

You got lost driving to a show in Chile, though.

We did! It was frightening. I was thinking, 'Oh, this is a bad idea'. But the upside of that is the people I meet every single day. The way I travel is so far out of the bubble - I have real conversations with people at gas stations, at rest stops, in cafes and diners, hotels. You name it, I have those and I love them. People think I'm unsociable and I'm not. If we meet as equals, I'm going to be very sociable.

You said the way you travel has made you love America more.

It has. I know it so well now, so many little towns. I met a woman out here in LA who's from a little town in Ohio, and she was talking about growing up on a farm sixty miles south of Cleveland. I said, 'Around Mount Eaton?' And it turned out her mother had gone to school there. The only reason I knew that was because it was the first of my bicycle rides back in 1984 or so, and we had a day off after Indianapolis.

I left the Holiday Inn near Richfield and rode fifty miles south on the little highway through Amish country to this town where I bought a sandwich at the general store and rode back again. It was the 4th July and I didn't know how to change a flat, so I was terrified the whole way there and all the way back, and that was my first hundred mile ride. And I'll never forget it. I retook that route again later, and as it's Amish country, it remains almost unchanged, thirty years on.

In Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road, you talked about the bike saving you.

The bike did save me, absolutely. I had nothing else to do; there was nothing else I could do. The telling episode was on the first day out. I'm in terrible weather, with logging trucks flashing me, and I'm miserable anyway and I'm lacking fortitude of any kind. And I thought, 'I've got to turn around, I don't want to do this.' And then the other voice went: 'Then what?' Because I had nothing else, and the stupid things people say to you at a time like that...'Oh, at least you have your music.' Fuck, what?! It's so maddening. I just wish people wouldn't say it, it's so stupid. You don't have anything. But it, the bike and the journey I took, absolutely did save me. But so did the booze and drugs! [Laughs]

You've just published Far And Away, a book of photos and stories from your bike trips.

That didn't start out as a book; it was online pieces. I got so into that: the combining of images and words, and the grafting of a real time travelogue memoir, a letter to a friend - it has the character of all that. So that volume collected the first four years of those, and since then I've published five or six more online. That's me, that's my prose writing, that's what I love to do.

Given the scope of something like Clockwork Angels, have you never thought of turning your hand to writing fiction?

It's not me. Honestly, I did try. But essentially what I want to do is look around and try to put it into words. That became what I want most, what I get the most satisfaction from. I still love to read over that stuff because it's like finding an old diary, the stuff that I was moved to record and then try to describe to others. That's a whole other set of rules and how you bring it alive, not just for your own memory, but how you try to portray this for other people. So that's plenty.

The band's long-term photographer and friend, Andrew MacNaughtan died here in LA during the mix of the album. You were very close to him...

We were very close to him, my wife Carrie and I, to him and his partner, Alex. It was a heart attack; he was 47. It was devastating, but more disbelief really, shock. It's still setting in. Anyone who's lost someone will know that you keep seeing them. I keep seeing him: 'Wait, there's Andrew...' It takes so long for the reality to set in and you stop seeing them. You don't believe it yet, and you're worried too, for me, for the survivors.

Here's a provocative statement for you: death is for the survivors, the bell tolls for thee. I guess I didn't come up with anything new there. So, my concern in all of this was to his family, and to Alex - especially Alex, as he's got no rights under Ontario law and they've been together eleven years. Do you know what that is in gay years?! It's like a hundred...But they were one of our favourite couples. We had so much fun with them, we did so much stuff together.

You've said that the lyrics to Camera Eye are an example of modern poetry. Does that mean they were the lyrical high ground for you?

To me, it's not one of the enduring classics. I think I did what I set out to do there and it's effective, but it's not as powerful as a song like Bravado or Animate, lyrically. There are ones I know that have said something really worthwhile, and maybe in a beautiful way, like Bravado - songs like that have helped me, which is a measure of their worth, I guess.

Helped how?

There have been several times when I've suffered from the hubris of having flown too high. The opening lines to Bravado read 'If we burn our wings flying too close to the sun', which is then resolved in the chorus, 'we'll pay the price, but we will not count the cost'. 'Put it behind you', basically; 'wish them well'. It was an early statement of that viewpoint. Several times those words have come back and soothed me.

As a band, you've never been afraid to evolve and try new things, but the change between Hemispheres and Permanent Waves is profound, like your full stop on the 70s era.

I know what you're saying; we did have several ground shifts like that. The whole 80s thing with Peter Collins and the massively intricate production, we loved all that. Then we kind of stripped down again; by Counterparts we'd gone back to bass, drums, guitar again and that was a direct reflection of the times; the early 90s. I remember the first time I heard Nirvana, and then Temple Of The Dog and Soundgarden and those bands. They influenced us the same way that punk influenced us: in a stylistic and artistic way. I loved the rise of those bands coming out of the northwest and the return of guitar driven rock. We were okay, we're a part of that. We've got guitars.

You say Rush is a continuum, but do you feel re-energised at this point in your careers?

I think so, perhaps. It has to be because we feel that way individually, which is why we are this way as a band. As team players, that's who we are, that's what this is, in the truest sense.

It's quite the team.

I think so.

TRACK BY TRACK: GEDDY LEE ON CLOCKWORK ANGELS

By Philip Wilding

SCORING SOUND TRACKS FOR MOVIES THAT DON'T EXIST, SWAPPING INSTRUMENTS WITH ALEX LIFESON AND WHAT IT MEANS, FOR RUSH TO HAVE A GOOD DAY AT WORK: GEDDY LEE TELLS US HOW THEIR EAGERLY AWAITED NEW ALBUM CAME TO BE.

CARAVAN

It was the first song we wrote from scratch, and we just wanted to get a different rhythmic vibe going. It's got that dynamic opening lyric too: it really sets the stage, and it's fun to write with a bit of a script, because you can have more fun with the sounds. We used to do that in the old days - make soundtracks to films that didn't exist - and that's kind of the attitude we took with Caravan. But musically we wanted it to be a little more raw and a little funkier, that's what we were after. It's white Canadian rock funk, not actually true funk, obviously.

BU2B

That came from an idea I had one night when I couldn't sleep. I've started to play with this notion of writing songs and then seeing if they stick with me. Writing melodies in my head, and then if they stay with you over a number of weeks - if they've got some sort of resonance - then when Alex and I get together, I try to get him to make what's in my head come to life. This song is an example of that process, and it just worked. It's a fun song, it's relentless and the new mix we've just done means it's taken on a different character now.

CLOCKWORK ANGELS

Alex brought me this crazy instrumental when we started writing, and we just added and added to it. I love it so much, and it's the one song I didn't know if people would 'get' the way we get it. I don't know why, maybe because it requires a bit of patience and it's a bit of a journey. But there's something about that melody and the way it came together that really works for me. It was a very difficult song to mix, I think it was the song I was worried about the most.

THE ANARCHIST

Alex and I had done a good jam, and I came up with this bass melody in the chorus. We both thought it was really infectious, so we just decided to build around that spirit. That was two years ago that we wrote it. It didn't really change much, that's a nice thing. Nick [Raskulinecz] made his comments about it way back then and we applied those ideas and then just left it. I thought it really lent itself to having strings added in those few sections - an almost Bollywood vibe.

CARNIES

It came from this jam that was done the same time as Headlong Flight, and I had forgotten all about it. I was in the studio and Alex hadn't come in for some reason, and when that happens I either jam on my own or look through the pile of unused stuff. And I found this opening riff, and I thought, 'This is a rhythm that we never play' - like, that slower vibe. But Alex had this melody line and I had this counter line weaving in and out of it and I had Neil's lyrics to work with by then, so it came together relatively quickly.

HALO EFFECT

That's a real change of pace. We wrote that at Revolution in Toronto. We needed something to give people a break, especially if you're talking about a concept of any kind. It just came from an idea Al and I had; the whole song was originally acoustic, and then we decided to darken every other stanza, treat it like a chorus even if the lyrics kept changing. But it worked out, I was really pleased. And Alex is such a nice acoustic player, it's great to get that into the sound. I love the way he does it, he's always sitting around playing the acoustic guitar.

SEVEN CITIES OF GOLD

We needed a keyboard part for this and we were in the mixing stage, and it's always fun to do an overdub when we're not supposed to. So I've got jetlag in LA, it's four in the morning; I called up and got the keyboard ready for later, came in and knocked it off and it worked. It's a huge addition to the song. It felt like it was an opportunity to get that live jam feel that we had on the last tour. This was written wanting to nail the feeling we had then.

THE WRECKERS

I saw this guitar of Al's that's tuned to Nashville settings, which is amazing: play any chord and it sounds like you know what you're doing. I started plunking on it, and I wrote the chorus and the verse, grabbed Al, and he started playing and writing the bass part. I'll be honest; it sounded a little like Barenaked Ladies! So we Rushified it. Al was going to play the bass - he said, 'I want you to play the guitar and I'll do the bass' - but I'm not such a great guitar player.

HEADLONG FLIGHT

From a jam that we did between the two legs of the Time Machine tour, written around wintertime 2011. Carnies and this song came from jams Alex and I did at my house. I'll be honest, it's a little bit manic. There's a whole section of Headlong where it's like us jamming Working Man on the Time Machine tour, going, 'How about we have a section where we just fucking go for it?!' It's one of the four solos on the album where Al's playing is brilliant; he really outdid himself.

WISH THEM WELL

I played it for Nick and he went, 'Not so much', so we put it away. Whenever Alex was away, I'd start hammering away at it. I said, 'I'm going to have one more pass at this motherfucker: I spent a couple of days on it, and the next thing you know, it was that song. I was so nervous playing it for the guys, because I'd failed twice with this fucker, and Al came in and loved it. So I felt like we'd saved the song and now it's one of my favourites on the record.

THE GARDEN

It was one of those few songs that come along where the lyrics just felt perfect. I loved the sentiment of the song, so I wanted the music to be heartfelt. It just flowed, and we had 'a good day at work', as we call it. We wrote The Garden in a very natural way, and when Nick heard it he didn't want to change a note. The only thing he suggested was leaving the drums out of the first part, which I think is great - it lets the song breathe, and then Rush show up. And I think the solo is one of Alex's best pieces of work.

WORKING THEM ANGELS: WE MEET PRODUCER NICK RASKULINECZ

By Philip Wilding

PRODUCER NICK RASKULINECZ ON AIR DRUMMING WITH DAVE GROHL AND GETTING RUSH TO PLAY FROM THE GUT

The Clockwork Angels story truly began in a room at the Beverly Hills Hotel over three years ago. The three members of Rush, sharing a sofa, looked on while producer Nick Raskulinecz - who had already worked with the band on 2007's acclaimed Snakes & Arrows album - paced the floor.

"I said, 'Hey, let's not make a record for radio, let's make a record for ourselves,'" says Raskulinecz, punching his open palm for emphasis.

Neil Peart calls Raskulinecz 'Booujzhe', after the producer suggested a series of near impossible fills that Neil might play. "He'll mime the drum parts with wild physical gestures," says Peart. "And sound effects: 'Bloppida-bloppida-batu-batu-whirrrrr-blop - booujzhe!' The 'booujzhe' being the downbeat, with crash cymbals and bass drum."

Booujzhe and Classic Rock are seated in a small anteroom in Henson Studios in Los Angeles, where Rush have been working on the final mix of their latest album, and you can see what Peart means. It's hard for the producer to contain his excitement at working with Rush, especially on the Clockwork Angels record. The walls and ceiling are covered with patterned red and yellow drapes, but it's Raskulinecz who's the real colour in the room.

"I said, 'Let's not think about traditional arrangements, let's not worry about how long the songs are; let's make a Rush album,'" says Raskulinecz, waving a finger for emphasis. "'I want you guys to be Rush in every sense of the word, and let's see what kind of record we get on the other side of the voyage: Three and a half years later, this is what we've got. There was never a conscious decision to make a concept album, or to have it be full of crazy fills and have the bass licks, you know...It just evolved. It's Rush, I didn't restrict them in anyway."

Things are busy for Raskulinecz here in Hollywood. He's travelled up from Nashville, where he lives with his wife and children, to finish the mix on Clockwork Angels in the afternoons. His mornings are spent recording tracks for the next Deftones album - he also produced their last album, 2010's Diamond Eyes. Not that he's complaining about his workload.

"I'm busy and I couldn't be happier about it," he asserts. "It's exactly where I've always wanted to be."

Raskulinecz first came west (from Knoxville, Tennessee) in 1995 with his band Hypertribe, who quickly became Monument after they discovered LA already had its own Hypertribe. Like a lot of young band's dreams, theirs died quietly somewhere along the Sunset Strip when their drummer unexpectedly bailed, leaving them with a lease on an apartment that Raskulinecz and the rest of the band couldn't afford. Then an old school friend from back home named Brian Bell, who was now playing in Weezer and recording the Pinkerton record across town in Sound City Studios, called and told him that the studio needed a runner.

"I went straight down there and met the studio manager and got hired on the spot," Raskulinecz says. "My first shift was 19 hours working through the night and that was it. I'd be getting coffee, cleaning toilets, total studio bitch. It was great, I loved it."

He learnt on the job, working his way up to producing his first album, More Than Conquerors, for a band called Dogwood in 1999. It went better than he dared dream; buoyed by his experience, he quit his job and struggled on as a freelance producer, bulking up his portfolio working with artists like Glenn Danzig and Duff McKagan. He was often broke, though, and close to calling it quits when he bumped into Dave Grohl, who he'd assisted at Sound City in 2001 [sic] when Foo Fighters recorded A320 for the soundtrack to 1998's Godzilla. Dave and his band were going to Virginia to make a record; did Nick want help them?

"I was like, 'Fucking yeah!'," Raskulinecz remembers. "Producing the One By One album changed my whole life. It took me up to a whole new level, where I'd been trying to be since I moved to LA. Dave, Taylor [Hawkins] and myself were driving down the 101 in Dave's Suburban, on our way to make One By One, and we'd just bought Vapor Trails, and One Little Victory was really big then, and the three of us were air drumming in the car and going, 'Yeah, they're back!' There was an energy and a fire on there that influenced us; the song Low on One By One is really influenced by that - just listen to it!"

Since then, he's produced everyone from Stone Sour to Alice In Chains to Evanescence. His career was already flying high when he read online that Rush were gearing up to record a new album.

"I'm a fan, I grew up listening to Rush; they're part of my musical palette, along with Kiss and Zeppelin and Queen, the Beatles," says Raskulinecz. "That was my music growing up. My then manager sent them some of my stuff and they invited me to meet them. I'll never forget it, I flew up there from LA, and pulled up at Geddy's house, knocked on the door and, boom!, there's Geddy Lee, and then there's Alex. We just talked and talked. I tried to play it cool, but it's Rush. I got excited as soon as I heard the music.

"My first impressions of the material that would feature on Snakes & Arrows? I thought that some of it was a little overblown - a little over-cooked, as Geddy would say - but I was still finding my space. These guys have a history, they know how to make records. I have a lot of respect for them as people, and as players, and their whole experience. I've learnt a lot from them. But to be completely honest, it was really easy for me to sit down with them and tell them exactly what I thought. And I think some of the things I thought might have been a bit shocking."

It was an approach he'd carry into the studio for Snakes, not least telling Neil Peart that he could work some more on his parts.

"I was a fan, but I'm also a producer, and I'm objective, and I've got very aggressive ideas about what I think things should be, and I'm not afraid to tell any of them to do it again," he says, getting to his feet for emphasis. "Case in point: walking into the drum room with Neil after he'd done a take, I turned the volume knob down in the room so no one could hear what I said to him. I got right in his face and went, 'Dude, let's talk about the verse for a second' And he's just sitting there looking at me stone-faced, you know.

"I remember the first time I did that, and turning around and walking back into the control room and inside, it's 'What the fuck just happened?' And Geddy's just sitting there smiling, and going, 'He's going to like you.' And that started my relationship with Neil. I think he was searching for something like that. I broke right through that wall. As a Rush fan, I know what I love about Rush and the things that I felt like had been missing from certain albums and where they were headed."

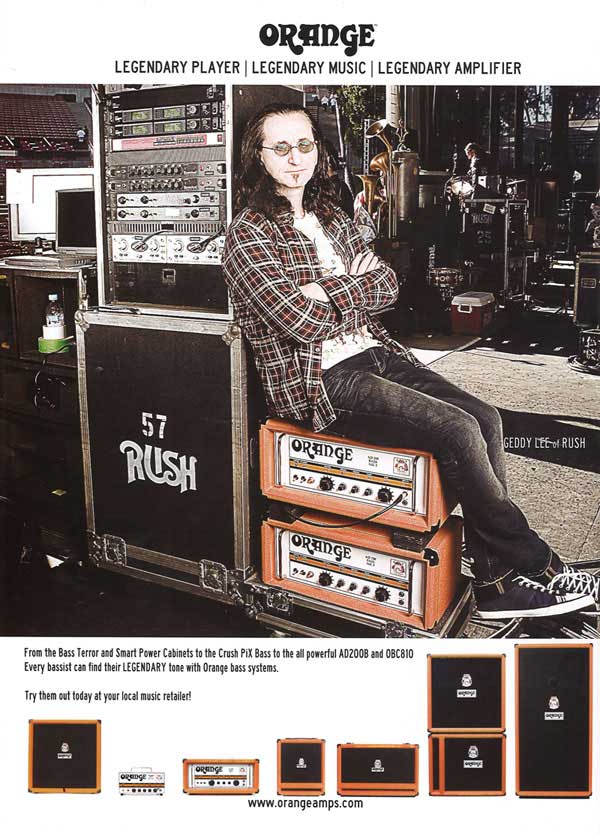

Raskulinecz even got them to bring their bass pedals back, much to the relief of many Rush fans - though he insists the band never once resisted the idea.

"The hardest part about the bass pedals was finding a set, because they didn't have them anymore," Raskulinecz says. "We called a company in Toronto and rented the bass pedals and had them shipped to the studio and Geddy's sitting there, we take the lid off and he's like, These are the ones we used on the Permanent Waves tour!' I was like, 'You sold these? Are you kidding me?!?"

The thing that Nick and Rush all agreed on from day one for Clockwork Angels was to get back to the basics that made up the band: bass, drums, guitars, vocals and bass pedals. Given, too, the band's desire to extend the jams and embrace the sense of freedom that had become a recurrent highlight (for both band and audience) on the Time Machine tour, Raskulinecz pushed the trio to just get in the studio and play.

"The biggest thing for me was for Rush just to be Rush, no restrictions. Listen to a song like Far Cry from the last album, the energy of it; that was a song I was involved in from the very beginning, and it was all about playing," he says; fingers waving around like two imaginary revolvers. "Play from the gut, don't obsess about it. I want to listen to Geddy Lee play the bass; he didn't write the bass solo at the end of Red Barchetta, he played it.

"That's the essence that I was trying to get at. I just hope that when the Rush fans listen to Clockwork Angels, it makes them feel like they were kids again, because that's what this record makes me feel like. I put it on and I'm young again, and I just hope other people feel the same way."

Q&A: GEDDY LEE

By Philip Wilding

FILM PRODUCER, BASEBALL COLLECTOR AND BLUE JAYS FAN, GEDDY LEE ON BEING SACKED BY HIS BAND, GETTING BACK TO BASICS AND WHY RUSH LIMBAUGH HAD TO BE STOPPED

Geddy Lee is seated at the main mixing desk in the Jim Henson Studios in Los Angeles where the band have come to finish Clockwork Angels. He leans back in his seat as producer Nick Raskulinecz stands next to him. Both are staring at the massive speakers attached to the wall, as if they can see the sounds emanating from them. As The Garden builds and falls in a wash of orchestral strings, Raskulinecz raises his hand dramatically, as the song hits some invisible point, and then stabs at a button on the desk. After the huge wall of sound that's been vibrating through the room, the silence is startling. "You see?" asks Raskulinecz. Lee nods. He does. apparently.

Twenty minutes later we're walking down the hallway through the studio's labyrinthine maze of corridors and ante-rooms. Along one wall stands a half dozen identical old tape machines, all seemingly in perfect working order. Out of a door to our left walks Alice In Chains' Jerry Cantrell. He shakes Lee warmly by the hand and, for some reason, pats Classic Rock genially on the back.

"Let's do this outside, it's a beautiful day", says Lee, heading to the sunlit courtyard. He points out Charlie Chaplin's footprints embedded in the concrete - Chaplin originally built the studios and shot both Gold Rush and The Great Dictator here. As we sit blinking in the light, a huge bust of Kermit the Frog bursting through the wall hangs silently over our heads.

Cheerfully, you refer to mixing albums as the 'death of hope'. Are you ready to give up yet?

We got a few segues left, and that's it. This last song, The Garden, was a tough mix because it's such a different song for us, with the textures and the orchestra. Originally we took it in a different direction and it just didn't have the same continuous feel - it started to feel like it was from a different record, so we took a step back and now I'm very happy with it. This side of the band I've always wanted to push more. The melodic side, the orchestration, the possibility of that. I guess you'd call it the softer side, I don't really see it as that - just more thoughtful, reflective maybe. So I'm really happy the way that turned out.

When word filtered down that you'd made a concept album, our first thought was, 'Is it going to be 2112 or Fountain Of Lamneth?'

Ha! Caress Of Steel part II! That's what we've been joking about all this time...We keep saying, it's Caress Of Steel all over again. Get ready for the 'Down The Tubes Tour' part two!

Alex said that it would take $1,100 to make another concept record; you said you'd want $10 million in 1970s money, what happened?

One of the great things about this band is that we really don't know what we're doing too far ahead; we just let it happen. Whatever's going to happen happens and sometimes it works well and sometimes it's a bit sideways and sometimes it's not so good. But I think that's part of the journey, right? Someone asked us in an interview, who is Rush? And the three of us just had no answer for him. It's such a stupid question in one sense, but it also makes you think about yourself in a kind of existential way, and I realised that we can't answer that question because we're constantly in search of that answer.

It's a strange thing to say, but this album really sounds like Rush...

No, I think that's true. I think this album really sounds like Rush, the essence of who we are. One of the things we agreed upon early was, 'Let's write a trio's album'. We thought we were doing that with Snakes & Arrows, but we didn't; we just made that record a little too dense. Going in to this, we wanted to have moments where it was just the three of us playing the way we play on stage. We had so many amazing jams last tour, like in Working Man, where we allowed ourselves to free form a bit. We enjoyed it so much that I said to the guys after the tour, 'Let's try to be that band sometimes on the next record'. It feels so essential and it's what we're about.

It sounds as though Nick Raskulinecz only encouraged that.

Yeah. We're a bit curmudgeonly, you get tied to your way of doing things, so it's hard to break out of that. But with a producer like Nick that has that kind of enthusiasm and confidence and also knowledge, it works. If any old person came in and started asking us to do some of the things he asks us, I don't think we could pull it off. But because we know where he's coming from and we know that he understands...For instance, he can sing you every note of every drum lick, you know. He's coming from the same place that we're coming from as musicians - he is a musician, he's got legitimate respect from us - so when he comes in the studio and asks us to try something else, we look at each other and go, 'I don't know about this'. We think for a second, and we respect the guy, so we do it.

Plus, Neil has been really open to rhythmic ideas from outside, a lot more open generally. Alex and I put together rough drum ideas when we're writing, and Alex is brilliant at creating rhythms, and so sometimes Neil will just use it, when it's right it's right. Same thing with his approach to Nick this year: rather than go through the whole process of writing the song and then having Nick come in and push him around, he let Nick push him around first.

It took you a while to get the album started, didn't it?

The record began reluctantly, that is true. We had done a long tour and we took a few months off and we were scheduled to start writing September 1, this past year. We'd finished the tour in July, and I went away for a month and came home, and it just felt like the summer had gone away and already we were getting back into work. So I wrote to the guys and said, 'I can't face it right now, I just can't. I just feel like we didn't have enough of a break. I know we wanted to come in straight away and be fresh and have our chops and all that, but I think my heart is just not in it yet: And Neil wrote back and said, 'So glad you said that first!' So we left it for a month, and then we got back in at the beginning of October. Alex and I started, and it was really hard to get going. But we had these jams that we'd done previously, to see if we could stay a step ahead of the game when we finally had to get something done.

I listened to one of the jams that we had, and it was ferocious. They were done when we were fresh from playing live and really in a good place. We just felt like we were communicating on stage, and that jam reflected that. So I said, give me a couple of days with this song, and we wrote this instrumental which we originally called Take That Lampshade Of Your Head. So within two or three days, Al and I were so excited, we were playing all kinds of effects and adding new parts, and all of a sudden we were back. We clicked in, and that song eventually turned into Headlong Flight. I prefer the original title though.

You're singing a lot more on this record, too.

It's just where we're at. The lyrics and the music we were writing lent themselves to melody. It was ironic, because in some of the songs where I was feeling a little bluesy, maybe, and wasn't sure that they were something I could make into a satisfying melody, the exact opposite happened, because it didn't have so many constraints: because it was a loose, bluesy feel. Like in Seven Cities, I could stretch out melodically, I could be a little more that guy, and it kind of put me in mind of the way I used to write when I was just starting. Everything Rush had kind of begun as a band listening to people like John Mayall; we liked American blues reinterpreted by British rock musicians. That was the thing that turned us on. And it kind of took us back there a little bit.

The songs started coming together over two years ago.

They did. We wrote Garden at the same time as BU2B and Caravan; Anarchists [sic] and Clockwork Angels, too, they were all two years ago. I'm the kind of person, when we write something, or even when we record, I don't listen to it everyday. Alex is the exact opposite: he's constantly listening to it and driving himself mental. So I didn't listen to those songs for something like a year and a half until we went back last September to start writing again. I hadn't heard them in two years almost, so when I put them on, I was shocked at how well they stood up.

You said that about going back to listen to Permanent Waves.

That doesn't always happen. You have all these reference points when you're working on something; the things that bug you and the things that are successful stay with you, so when you're listening to them constantly, you're reinforcing either one or the other. When you've forgotten about the song, forgotten about what surrounded it, it becomes a new thing again, so you can judge it a lot more clearly. Permanent Waves had shed all those things for me and it sounded great.

It feels like you've gone full circle on this album - back to writing together and jamming, extended pieces, more experimentation. Alex says it's because he's 58 and doesn't care what people think anymore.

He looks 58! I don't know why we took so long to get to that place, you have ways of writing and sometimes you ignore the obvious. And the obvious always comes back to what you are as a band, and we're players first, always. But somewhere along the way we missed that connection on how that playing informs the writing and that's a really big part of it. We changed our approach to song-writing and somehow forgot that's how we used to write in the old days that that's how we wrote Spirit Of Radio, that's how Tom Sawyer was written, all of us together in a room jamming. So without realising it, our playing was informing our writing right from the get go, and then we went away from that. We separated that from what I guess is essentially Rush.

You've always resisted repeating yourselves; you've been quite dogmatic about it at times...

The one thing that Nick has shown us is to not be afraid to respect our accomplishments of the past. And it's not that we borrow from our past, it's a different thing. It's like saying, 'That's a thing we know how to do really well'. We spent most of our lives running from anything we'd already done. Some would say it's not a forward move, it's a sideways move, but nonetheless we're trying to learn more, we're trying to get to a better place finally: to write that song that we feel is better, play those pieces that reflect a growth. You get lost along the way, but that's what we've tried to do.

The Time Machine tour obviously energised the three of you, even if you were worn out at the end of it.

It was just a great experience for me. I think it helps, too, to have children that are a little older and feel a little less guilt about being away from them. I think the time of our lives makes us more appreciative of the positive things that we have. I've heard sports guys say this quite often in their last few years, they get invited to an all star game or whatever, and when they were younger, they didn't really experience it with the same emotion that they do later, and I understand that completely. Now, whenever we hit the stage it's like an opportunity and I don't know how many more of those opportunities one has in one's life. So, I think we all feel kind of privileged and I know that Neil has come to a much happier place about touring and playing live. I think he's reconnected with that being an essential part of what a musician is. It was torture for him, and it's still very difficult, just given the kind of person he is, just in his private nature. He's come to terms with the fact that if you are a musician and you are still wanting to hone your craft, you have to play. It's just what you do and that's huge for him and, of course, it reinforces our feelings.

I think that attitude made every night on stage so much more enjoyable, and the way the show was structured was really quite fun, it was really hard. Especially as the tour winds on and you're running out of gas. But we had those moments - Camera Eye was one of those, and Working Man was one of those moments where you just...You could tell everyone was so into it, in that moment and loving the fact. When you start a tour, your chops are decent, but they're a little clumsy and we just got our playing to a point where I don't think we'd ever gotten to before, ever. I don't think we ever have played with as much confidence and fluidity as we did on that last tour, let's hope we can repeat it!

When we spoke to you in London after the O2 show, you talked about pushing boundaries live...What did you mean?

Parts of the show kept getting better for me, and I felt like we really were playing so well. It got looser and more free, and we were pushing the boundaries and trying to see if we could hit a breaking point almost, just pushing and pushing. It was a great experience, we're trying to make this next tour a little different, to give people a different experience, slightly.

But it'll still feature the Time Machine stage set, all the bells and steam whistles?

There'll be some tweaks. We've got lots of ideas. The steam punk thing is definitely part of it, we just jumped the gun. We got excited about it, which is good at our age.

After years of resisting it, you're finally talking about doing some festival shows.

I think we will do some festivals in the future, because I think it is an interesting way to get across to people who maybe wouldn't come to the oppressive idea of a Rush show...Three hours of us, some people don't want that! We played more outdoor festivals on the last tour in North America, and we proved to ourselves that we could do it and still maintain our vibe, our thing. It was just a nice experience, so we're learning not to be afraid of those. We were such control freaks for so many years: we didn't want to go anywhere we couldn't control the environment, put on our show. So we're learning that wherever we play, that's our show. And at the end of the day, it's about the playing, and the songs, and it'll be fine.

In the five years since Snakes & Arrows your public persona's changed again, not least because of the Lighted Stage movie. People like you guys...

There's been a huge shift in perception of us, but just because we're nice doesn't mean you should like our music. The film is very watchable, it's got a great pace to it, and it shows up in all these places where you're trapped, like airplanes or a boring Wednesday night on the movie channel, and people are watching it and they're finding the story interesting and they're corning away with a different impression of us. And I see it on the street, I see it wherever I travel...I'm far more recognisable than I've ever been. It is what is, there's good and bad; I can't accept the good and complain about the bad, that's my attitude. We get into restaurants a little easier.

Neil's never seen the movie, but have you watched it again since it was made?

When I came home from this first part of the mixing session after Andrew [MacNaughtan, the band's long standing photographer and friend] had passed, I couldn't sleep, and so I got up and was nursing a Macallans, flicking through the channels and I saw it was on. So, and I don't know why, but I just started watching it. I started seeing things in it that I hadn't noticed the first time, listening to things a little differently, because when I saw it the first time I really didn't want to, it was hard to watch. Watching yourself talk about your life, it's not for me. But I started watching it again and started thinking, my god, how strange to see your life up there on a television show in the middle of the night. And I thought about all the different people that can't sleep and are having the same experience I am, but they're watching about my life! It's just so bizarre.

But was it a good experience?

It was all good. It was interesting to hear everyone's take on us, the kind of things that the other musicians were saying and how important our music was to them. The stuff we say about ourselves, I hear that all the time. But hearing other people talk about you and seeing what you mean to them...

Hearing Billy Corgan talking about what the song Entre Nous meant to him was actually quite affecting.

Yeah. Billy blew my mind in that. The things that he was saying about his relationship with his mother, and what that song meant to him...And even Trent Reznor, it meant a lot to me to hear those guys talk about our work. Because you don't start doing this for any other reasons but your own, and, of course, forty years later, you never expected that you'd still be doing it...And then to hear other people describe your work in such a serious light, it just makes you feel like you've lived a life, and that's such a nice feeling. That and getting over the shock that a filmmaker made us interesting...

When you saw the first edit, you and Alex said you liked it, but asked if there could there be less of you in it.

We meant it! Not that they listened.

One revelation in the film is that your long-standing manager, Ray Danniels, fired you and the band went along with it.

He really did! That was pre-history really. We hadn't recorded yet and were still in our embryonic stage, and he came along. He had no real reputation yet as a manager or anything. He was just kind of an agent working in Toronto back then. So he started directing the band, and he just thought I wasn't suitable for whatever reasons he had. I don't know whether it was the way I looked, or my religious background - who the fuck knew? Anyway, he influenced them and they went along with it, Alex and John [Rutsey], and I was out. I was out! They kicked me out!

We were a four piece at that point. My friend Lindy Young - who is now my brother in law, my wife's brother - he was the piano player in the band, so this is way back, back when we were just playing little drop in centers, that era.

But they basically kicked me out, and I started a blues band, and I was doing gigs and was, frankly speaking, doing better than they were! And then I got a call from John and he said, 'Can we get together? Basically, can you come back? We're sorry.' They had to go through whatever they went through, so we tried it again, and that's really when the band started. Then we became this three piece, and then we were really going in the same direction.

Sam from Banger Films (the company who made Beyond The Lighted Stage) says that if you and Alex hadn't been such outcasts living in the Toronto suburbs, there probably wouldn't have been a Rush. Fair comment?

I think that's pretty true. I think it makes you want to escape your surroundings. I think most musicians and artists probably have that in common, where their art is a vehicle for escape from what they believe is a boring existence.

It was certainly that way for me, and I think that's why a lot of our fans identify with us, because a lot of them are from the suburbs and a lot of them had the same feelings, the same frustrations. And so, to a certain degree, we're one of those people who somehow managed to get away.

Subdivisions crystallises those thoughts into five minutes plus.

On the last tour, Michael Moore came to one of our shows, and we found out that he's a big Rush fan. He was saying that very thing to us about Subdivisions, and he quotes Subdivisions at the top of his last book. And I thought that was fascinating, because I have a lot of respect for him and I love what he does; he's smart, and a moral guy. So Neil says to him, 'Oh yeah, which line?' And he put the poor bugger right on the spot and Moore's going, 'Oh...I...', and he's sweating and trying to remember exactly which line he used. I just wanted to grab Neil and shake him. Put the guy on the spot or what?!

Your audience really spans generations now: you're talking to dads and their kids these days. That must be a thrill?

It really is amazing, I love it. There's dad and mom and the two kids, and why does that kid not have earplugs on? Why is that guy holding a baby up? Put the baby down! Leave the building with the baby immediately! There are about six people every night that I want to scold - what is wrong with you? This is cruel and inhuman treatment of children!

Talking of cruel and inhuman, you've recently told right-wing American firebrand Rush Limbaugh to stop using your music on his radio show.

I didn't know he was using our music. Apparently, he's been using Spirit Of Radio for quite a few years; we didn't know that. I wouldn't know where to find his radio show, he's such an offensive human being; I try not to bring that into my life. Anyway, this gentleman who worked for The Huffington Post wrote to us and made us aware of it.

We had a similar thing happen with Rand Paul, the Libertarian candidate - he's like a Tea Party guy, he's Ron Paul's son - earlier this year. We heard he was using our music on his campaign and actually quoting lyrics of ours, and we sent him a nice letter saying, 'Please don't do this'.

I don't want to be seen to be sponsoring these guys. A lot of situations you can't control how your music's used. You don't want to get caught up in it too much, but some people put you in a position where you have to separate yourself from it.

On a happier note, your baseball team, the Toronto Blue Jays, play Spirit Of Radio through the PA each time they score. Which isn't so often...

I like that. Sometimes the players choose their walk up music and this catcher, who I've since got to know, Gregg Zaun, he's now retired from the game, but the one experience I had, I came to the game and it was the first time in a while. I'd been on tour for most of the season, and they played Limelight as he came on deck circle, and then he hit a home run. So he walked round, and as he was coming back, he pointed at me as everyone applauded. That was kind of a sweet moment I won't forget.

Something else the film turned up was your room filled with baseball ephemera at home. You just picked up a signed Fidel Castro ball, didn't you?

I did, yeah. No one goes in that room apart from me. I started collecting baseball stuff about twenty-five years ago. I stopped for a while, because things were getting really outrageous. When I started collecting, it wasn't such a big deal to buy somebody's signature. But with the boom of the 90s it got crazy; all these new millionaires were looking for things to collect: wine went crazy, collectibles went nuts, so I kind of came out of that. But in the last few years I've got interested again, because the upside of having a boom market is stuff comes out of the woodwork. So I started noticing rarities that I'd always wanted and had no access to: game balls, different players that you never thought you'd see on a single signed baseball, the kind of thing that was inherited within a family and they now realised they could make a few thousand dollars from it. So it helps them, and then it goes into my glass case.

You've bought the film rights to a book about baseball; you're in the movie business now.

Yeah! It's called Baseballissimo, written by a guy called Dave Bidini. It's non-fiction, and we're kind of fictionalising it, we're taking a lot of liberties with it. I've known Dave for a long time; he's a musician who played in a band called The Rheostatics. Actually, he knew Neil long before he knew me. He went off to live in Italy in order to write the book, and he came back a year or so later and I was so thrilled to read what he'd come up with. I found it to be such a charming story, about something that most people don't realise: that there's such passionate baseball fans in Italy, and how Italy got introduced to the game through the GIs at the end of World War II.

People love books, it doesn't mean they have to option the movie rights...

I thought it would make a great film. I have this bugaboo about great Canadian books that get optioned and then made into shitty movies. So I just kept saying to him, 'Make sure someone doesn't fuck it up!' And in the meantime I had been talking to a friend of mine here in LA about turning books into films. I find it really interesting...It's difficult, more unsuccessful than it is successful. I kind of thought, 'What's involved, maybe this is something that I could do?' I had this conversation with Dave at one point and he was having some difficulty in getting someone interested, and so I started putting people together to talk about it. And Dave called me up one day and said, 'I want you involved in this project, you speak for this book way better than I can, why don't you help me get something going?' Long story short, I optioned the book and together we'll find a producer and I hope we'll do it properly.

Will we be seeing a Geddy Lee original soundtrack?

No. It does interest me, but not for something like this. I know Alex has done it numerous times. Plus, he's a great actor too, he has all those tools at his disposal...

His performances in your short films are nothing short of remarkable.

I always think of the most ridiculous get ups for him: 'Hey Al, how about you play a real fat guy?' He really takes to it. [Laughs]

They're brilliant fun, especially as everyone thinks you're so po-faced as a band.

Nobody takes the piss out of themselves to the extremes that we do. The first time I saw Jethro Tull was on the Thick As A Brick tour and their production was so much fun. What a lovely bonus to give an audience that's sitting there for three hours listening to this intense music! And our music is a little on the bombastic side, so I think it's nice to give some candy.

Which is going some, considering just how serious your fans can be.

They've made such a bond emotionally with the music that it's hard for some of them to take it lightly. Some fans were upset that we were on the The Colbert Report and that he interrupted us in the middle of Tom Sawyer. It was funny, and we were obviously in on it, but to them it was sacrilege. Lighten up a bit, would you? We're just having fun. That stuff's harder to come by than you might think sometimes.

SEALED WITH A KISS: GENE SIMMONS ON TOURING WITH RUSH

By Howard Johnson

KISS CO-FOUNDER GENE SIMMONS FONDLY RECALLS THE DAYS WHEN A FLEDGLING RUSH WOULD REGULARLY PLAY SUPPORT TO THE PANSTICK-SPORTING ROCKERS

Everybody knows that Kiss bassist Gene Simmons has a long tongue. And most people know that he was partial to using it on the 4,500 or so groupies who had the dubious pleasure of sleeping with the frontman in his codpiece-wearing, fire-breathing heyday. But on the rare occasions when he wasn't indulging in such shenanigans, Simmons always put his tongue to another good use - hyping his own band. With the finely-honed instincts of the born hustler, Simmons never missed an opportunity to tell the world that Kiss were louder, wilder, crazier than the rest of his 1970s rocking competition. So even now, when he agrees to talk about his admiration for a band with a four-letter name that isn't Kiss, it's worth sitting up and taking notice.

"We took Rush out as our opening act on either our first or second tour, I can't remember which," he explains. [The first dates the bands played together were September of 1974, two months before Kiss's second album, Hotter Than Hell, was released]. "We were in a weird situation where we had alreadly started headlining some 3,000 seaters even though we hadn't had a hit record, so some of the dates were pretty big. I'd heard Working Man somewhere or other, and to me Rush sounded like the Canadian Zeppelin."

Simmons breaks off to do a fair-to-middling impression of Geddy's Plant-influenced scream on Finding My Way.

"So they had the kind of leanings that struck a chord with me. Plus they played and sang really well. Our point of view from the very start was that the entire concert experience should be a reflection of the headlining band, so we always took great pride in offering support slots to bands we liked. We were about giving the people who came to the shows a real bang for their buck, so we never worried about money and buy-ons and all the rest of it. The attitude was that if the package was good, then the money would take care of itself. Our opening bands were a reflection of us. We never pulled the sound down on them. We always gave them full lights. It was a cut-throat business, but we never did those things. We gave first tours to AC/DC Judus Priest, Iron Maiden, Bon Jovi, Motley Crue, a whole bunch of acts...Rush was one of the first acts that we gave a break to - and time has judged that we made a good decision."

Neil Peart had already replaced John Rutsey on the Rush drum stool at this point, but hadn't yet shifted the three-piece towards a more progressive style. Yet even at that early juncture, the band seemed pretty, well, 'musicianly'. Didn't that worry Kiss, who for all their many attributes are not and never have been virtuosos?

"They weren't slack," concurs Simmons. "And that was a great thing. Look, if you're in the gym and the guy who's next to you can lift more than you can, then you want to compete with him and you want to be better than him, right? And anyway, you always have to be delusional when you get up on stage. It's what makes you a champion. I was never concerned about who we were putting ourselves up against. You could have had cellist Yo-Yo Ma on the bill, who's a way better musician than I'll ever be, and I would always have backed myself!