Like Clockwork

By Andy Hughes, Bass Guitar, July 2012, transcribed by John Patuto

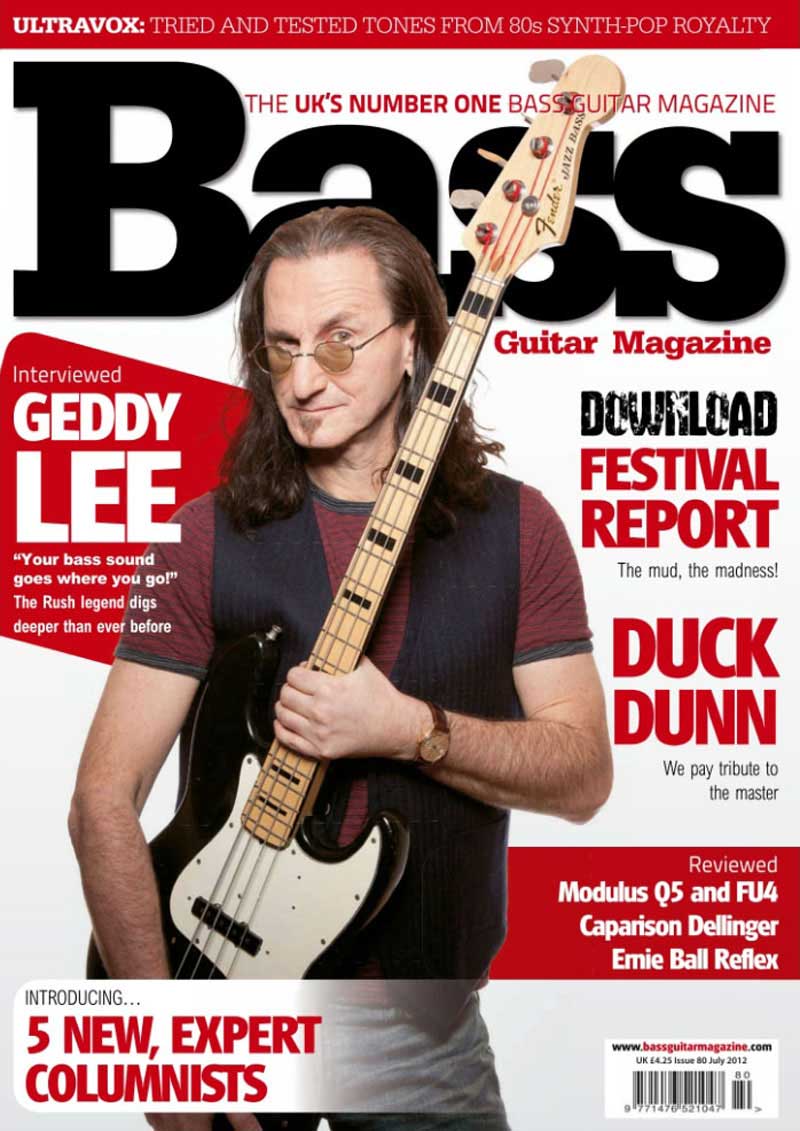

Geddy Lee: The man once called Gary (true!) talks tone, touring and tricky bass parts

Like everything to do with Rush, getting ready to take the band on the road takes time, planning, and lots of meetings. When we meet the Canadian trio's legendary frontman Geddy Lee, he is due for the next in a series of two-hour sit-downs with his keyboard tech to work out the finer points of conveying the band's newest output, and some old favourites, to the waiting masses around the world.

It's been five years since Rush released a full album, but that's not to say that they've been idle: a large chunk of that time has been spent touring and writing the new album. "We're always excited to go into the studio and it's something we always look forward to," says Geddy. "The writing process for a new record is probably the most rewarding aspect of what we do, aside from having a really good gig."

The secret of longevity in this business is the development of your band's style, Ai musical approach, and technical skill. For a bassist as technically gifted as Geddy, it's no surprise at all that he embraces the notion of development. "I always have an idea of a new place I want to reach, either sonically, technically, or both, trying to improve on where I was last time," he tells us. "It's a funny thing, but when you've been around as long as us, you sometimes end up in a place that you forgot you were in 20 years ago! I listen back to the last couple of albums and think that I maybe want to move on soundwise, maybe get a little more aggressive in this area or that, and then I listen to what I'm doing and think, hmm, that was the way I was playing around 1981. In a long career, you sometimes forget your own past, and maybe that's a blessing.

"What I'm doing at the start of a new record is to fine-tune this thing called my sound. I want to have it big and bold, but at the same time, I don't want to dominate the whole track. What helped us this time was that we made a conscious decision to limit the number of overdubs we were going to put on the album, to retain a bit more clarity. With [Rush's 2007 album] Snakes And Arrows, although we love the record and we love the songs on it, we felt that we overdid the overdubs and made the record a little dense. The sound that I have is the result of the experiments that we try out on the road. I experiment with my sound in what amounts to a live experiment room, namely the venues in which we play. We tour a whole bunch of different venues that are all fraught with their own audio issues. I aim for an on-stage sound that makes me feel like I'm filling the bottom end of the room, and yet I'm looking for the definition that sometimes it's hard to push through in an echo-y arena. So I take that sound that I've developed live, apply it to our writing, and see what suits the particular style of what we're writing. It's usually a matter of fine-tuning, which goes on in the earlier parts of the tour. It's not broad strokes; it's really a tweak here and there."

This represents a technical challenge, Geddy adds: "I run so many lines out to my front-of-house sound mixer, Brad, that he has a lot of options. I have four lines going out, and Brad will mix and match to get an interesting sound each night. I know that both he and my monitor guy take my DI sound and they put their own modelling on it. They can even take my sound, ignore it, and re-model their own sound and then feed that back to me, which puts an interesting spin on things."

But does that mean that in addition to manning the bass, adding in live and programmed keyboard sequences, and singing lead vocals, Geddy also has to have an ear on a particularly tasty sound mix, and memorise it for the next show? Fortunately not. Step forward Geddy's right-hand man, bass tech John McIntosh. "John remembers everything!" confirms Geddy with a wide grin. "He keeps track of all the settings that we use, so he has all that information. He can find the settings for a particular piece that I liked and remembered, and he'll be able to set it up again for me. John's a great guy; he's totally inside the instrument. This year we did some experiments with pickups. We have a technician who winds pickups for us, so John set up four very similar basses with four different sets of pickups, but with the amps and speakers set the same way. That way we could analyse just the effect of each set of pickups on the sound. It was really interesting."

Although Rush have spent decades pioneering new ways of making cutting-edge rock music, Geddy is not always keen to abandon his tried and trusted bass sounds in favour of new and untested possibilities. He explains, "As a player, when I find a sound I like, I tend to stick with it, and just leave it. I don't want to mess with it, once I've got to a place I like - but John is really good, he's always throwing different options at me, which is stimulating. It's good for me. During our downtime, John got the sound of these different pickups, made me a CD of each of them and sent it to me. I wasn't too interested in thinking about my bass sound when I was on holiday, but as soon as I got back to work, I was keen to hear what he had done, and it worked out well, because although my main bass remains largely unchanged, what we did was use some of the different basses on three or four tracks of the album, just to utilise different pickup sounds."

In keeping with this conservative approach to his sound, Geddy is equally reluctant to work with new bass guitar designs. As with all top-line musicians, Geddy is constantly offered new and exciting basses to try, but he remains faithful to his Fender Jazz. "I've always loved the way it sounds, and the way it feels," he says. "It's exactly the right bass for me. The manufacturers know that I'm a Fender man, but they still send basses to me, and some of them are beautiful instruments and I like them, so I do try and find a way to use them - but the sound I want on record is still that Fender Jazz sound."

He adds: "It's funny because when I started out, my identifiable sound was the Rickenbacker, and I played that for many years. I think it was on the Moving Pictures album [1981] that I started adding in the Fender. I used it on 'Tom Sawyer' and a couple of other songs, and most people just assumed it was the Ricky. Then I went away from it for a while and started experimenting with all kinds of different basses, like Steinbergers and Wals, which were all good instruments in their own right, and suited where my head was at sonically at that time. Then around the time of recording the Counterparts album [19931 I decided that I wanted a ballsier, deeper sound, a more rock sound, and that's when I returned to my 1972 Fender. I haven't really looked back from there. It's become a part of me."

The phrase 'If it ain't broke, don't fix it' comes to mind, we tell him. "I think you're right, although around that time I started trying out the Steinberger because it was drastically different to the Rickenbacker. The Rickenbacker was a very heavy, unwieldy bass to play live. I was playing a lot of keyboards on stage then, and I was going back and forth sometimes three or four times in one song, keys to bass and bass to keys. So I thought I'd try the Steinberger because it has no headstock, and it's a shrimpy little thing, a lot lighter. I figured that if I could get the sound I wanted out of it, it would be a lot easier standing surrounded by all this technology with far less risk of knocking a mic stand over or hitting something as I moved around. So I tried it, but ultimately the sound was not satisfying to me.

"I then started working with Peter Collins in Britain, and he owned a Wal bass, and the only other person I knew of at that time who played a Wal was Percy Jones of Brand X and I'm a big fan of his playing. I started using it, and the Wal had quite a sharp sound, it cut through things quite nicely and brought a funkier sound to my playing. This was the time when I was experimenting quite a lot. I was making the transition from a grinder, a fast-licks kinds guy, to someone with a more funky edge and a rhythmic approach. I had a relationship OS. with Wal and they made some fantastic instruments for me, and that ran for a couple of albums and a couple of tours, and that's when I made the move back to Fender. It was when we decided to get back to being a three-piece rock band again. I have quite a few Jazz basses in different styles, and I rotate four or five of those with different tones in each. I still have my old Rickys and I pull them out now and again for fun."

One song, 'The Anarchist', from Rush's new album Clockwork Angels, demonstrates that whatever else Geddy does when writing his bass parts, taking the easy option is simply not up for consideration. Part of his ethos is making each song sound as exciting as he can make it. "I go for that excitement without necessarily thinking too much about how I will deal with it in terms of reproducing it on stage," he says. "When it comes to rehearsals for the tour, I'm going to have my hands full learning that bass part, and also the vocals that go with it. I always want the best bass lines I can get for any song. Any one of us may write a simpler part initially, and then I'll want to make it more aggressive, or more interesting, or Nick [Raskulinecz, co-producer] will come to me and say, 'That's a great bass part, but it doesn't really add another dimension to the sound of the song'."

As for effects, Geddy is happy to leave them in the hands of his faithful tech. "John is a major gear-head," he tells us. "He's always on the look-out for the newest things. In the chorus of 'The Anarchist', there is some double-tracked bass in different octaves, so when we go out on the road, I'm going to need an octave-divider. He'll go out, and boom, there will be five octave-dividers for me to try out. If I want to put some phase on, he'll find the right phaser for me. John really understands all these devices, and he knows how to get the best for my sound. He's improved my sound so much with that attention to detail that he brings. I'm far more interested in getting a good solid basic bass sound, and then concentrating on the playing and the notes. I look for the sound I want, and I don't want to get distracted by all the gear that goes into making it. Besides, I work with a guitarist, and all guitarists are relentless gear-heads, and they're all about experimenting. It's where the old joke comes from - you tell a guitar player that the sound he has is great, and he'll say, 'Good, I'll change it!"

Every bass player eventually finds one particular piece of equipment that lights up his or her life, the 'old faithful' that is an integral part of their individuality as a musician. You're probably keen to know what piece of kit occupies that space in Geddy Lee's rack? "I'd say the Parker Speaker Simulator is a quintessential part of my sound," he advises, with no pause for thought. "I discovered the Parker a few years ago when Alex [Lifeson, guitar] started using one with his guitars. I added one into my rack, and it's enabled me to move away from the big loudspeaker sound. It has a very interesting tone, and it's now an integral part of the sound I get with my Fender basses.

"I use a lot of interesting devices. I use a Sansamp for distortion and bottom end, and I use Orange amplifiers that I set really full on to give me the sound of speakers dying when I need it. But both of those are replaceable as pieces of equipment: there are other makes and models out there that would do the job well enough for me. The Parker has an indefinable aspect about it, though, and that is the one essential ingredient in the sound I create. Ultimately, your sound as a bass player comes from you; it comes from your bass and your strings and your fingers. You can put it through all kinds of different gadgets and sound enhancers and different effects, but at the end, it still sounds like you. Your sound goes where you go."

Any learning bassist, and even a fair few who have reached the status of professional player, would still love to catch a few words of advice from someone of Geddy's musical pedigree - so here they are.

"I think, aside from the standard, boring, but essential dictum of practise, practise, and then practise, my advice would be to keep an attitude of being open to other players. Listen to as many players as you can that you admire, and find out what it is they do that you like, and try to bring that into your own toolkit. I learned by ear; I didn't go to music school, so I learned by admiring other players. So when I listened to Jack Bruce, I became obsessed with the sound he got on [Cream's 1966 single] 'Spoonful', and the way he moved his hands up and down the fingerboard with such a fluid style.

I was fascinated with Chris Squire, and the way he wrote those melodic bass parts for the Yes tracks, behind, alongside, or sometimes stepping out in front of Steve Howe's guitar work. I think it's important to have heroes, the guys that play how you would love to play, so pay attention to that individual ingredient that you like, and work on weaving it into your sound. It's not that you want to sound like those players, but you want to be able to do what they do, in your own way. I have always found that the more influences you have, the less easy it is for anyone to hear or work out what those influences are, because you work them into your own style of playing."

He continues, "The dangerous thing about getting to a good level as a bass player is that you might plateau, and become satisfied with the level you have reached, and stay there. I think you always need to have an approach of over-reaching in your playing, and always look to do something more complex and more dynamic, and always be looking to develop the way your bass sounds. and the technical aspects of getting that sound and making it your own. Take a step and risk failure, but take the step. It's OK to enjoy that step for a while, because that gives you confidence, and a confident player is a good player. So if, for example, you decide to bring a funky slap style to your playing, and you get it, it's fine to stay there for a while and enjoy it, and refine it. Once you've really mastered it and refined it away from the gimmick of the original sound you got, you don't have to go rushing on to the next thing. But just don't get too comfortable so that you stay there and never advance from that level."

At the time of our conversation, Geddy is about to start rehearsals for the band's world tour, which will be in progress by the time you read this. It's a complex business, given Rush's willful enjoyment of complex arrangements and lengthy songs. He explains: "I rehearse the playing first. I try to play a song so many times that I can allow myself not to concentrate on it every second of the time, and then I can start to bring the vocal parts into play as well. There has to be a degree of auto-pilot to be a singing bassist, so you can play without thought and put your effort into the vocal projection. You need to concentrate on the vocal when you sing, but in between the lines, or the instrumental breaks, you can think about your bass playing, and bounce back and forth between the two. Getting to a comfortable level with a new song depends on how complex the song structure is, and I don't mean how complex the bass or the vocals are individually, it's about the line between the two."

He adds: Some songs sound relatively simple from the vocal sound, but the bass part is so out of sync with the vocal structure that it becomes a nightmare to get the two running together, and that is hard to learn. To me, the playing and singing of a vocal and bass line that are utterly unsympathetic to each other is the hardest part of what I do. That can take weeks of intense work for some songs. The worst thing you can do is not serve the song properly on stage like you did in the studio. That applies especially with our audiences, because we know that a lot of them will know the songs note for note, and they'll know if I am not doing the proper lines, and they'll be silently accusing me with their eyes, saying 'Shame on you! You cheated us!' Ha ha! It's a good discipline for all of us... we know that they know."

Geddy concludes: "Every minute of the show needs total concentration throughout the time we are on stage. I have to say, it takes its toll: after 60 dates, we're ready to stop and rest. Going out night after night with the intention of getting it perfect every time can really start to fray your nerves, but that doesn't mean that we don't love doing it - the feeling after a great gig is one of the best things in the world. We never ever get tired of that, which is why we work so hard to make the next show the best ever."