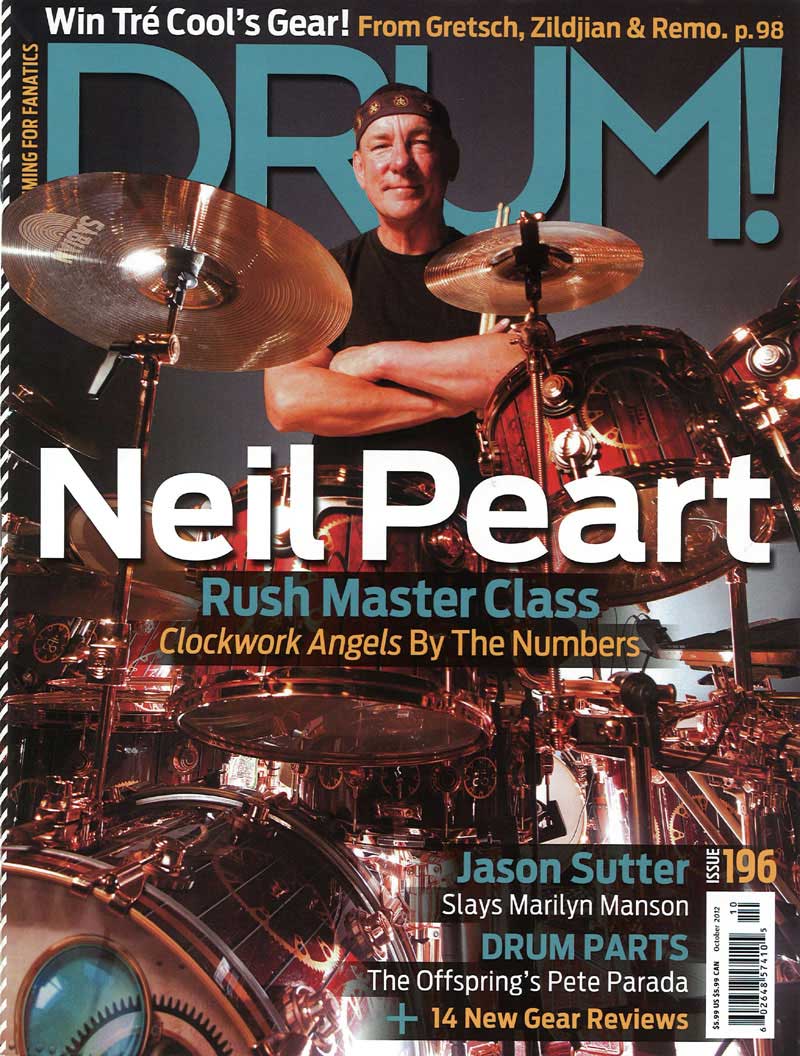

Neil Peart: Master Class

By David E. Libman, DRUM!, October 2012, transcribed by John Patuto

We sit down with the Canadian prog giant for an in-depth discussion of his approach on Rush's latest album, Clockwork Angels, to determine what it takes to play like Peart - with or without the 360 degree drum set.

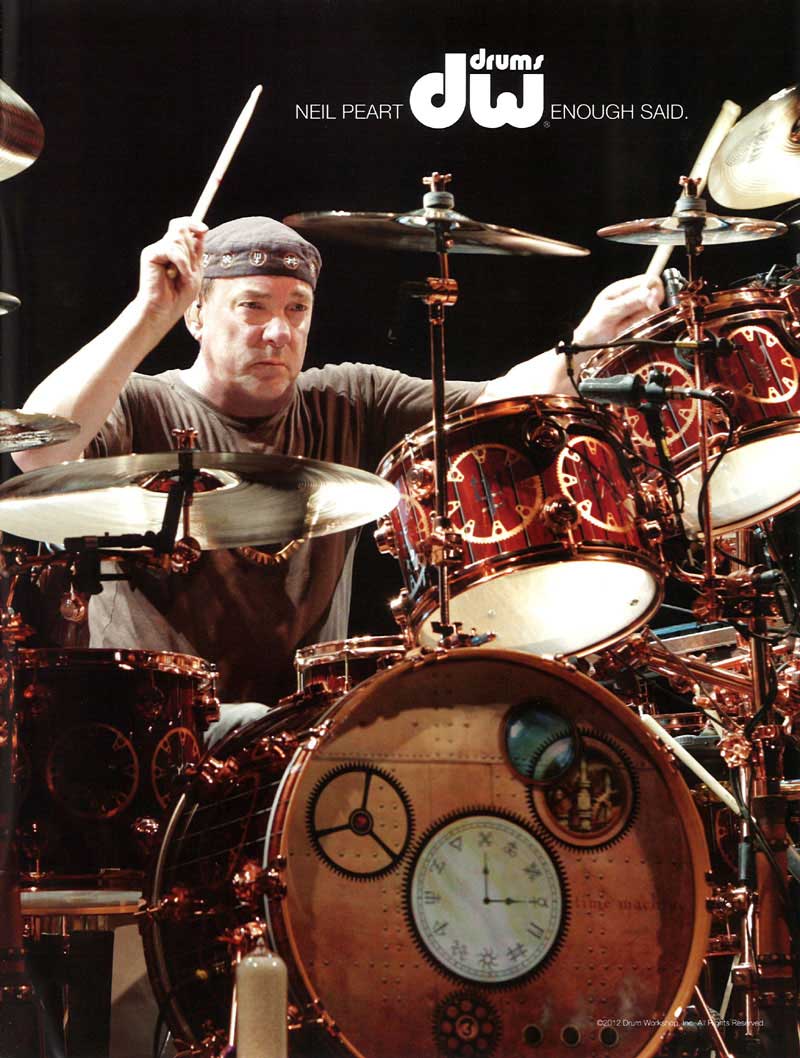

Lots of people play drums; fewer make a living doing it; even fewer get famous; and a very select few achieve the sort of legendary status where the general public knows their name. Neil Peart is one of the select few who sits atop this drumming pyramid. He has occupied the drum throne for Canadian progressive rock trio Rush for 38 years. Always the intellectual, Peart acknowledges, "I'm approaching my sexagenarian years," which is not nearly as perverted as it sounds. It merely means he's entering his sixties. This makes Peart just slightly older than his two bandmates: Geddy Lee (bass/keyboard/vocals) and Alex Lifeson (guitars/keyboards).

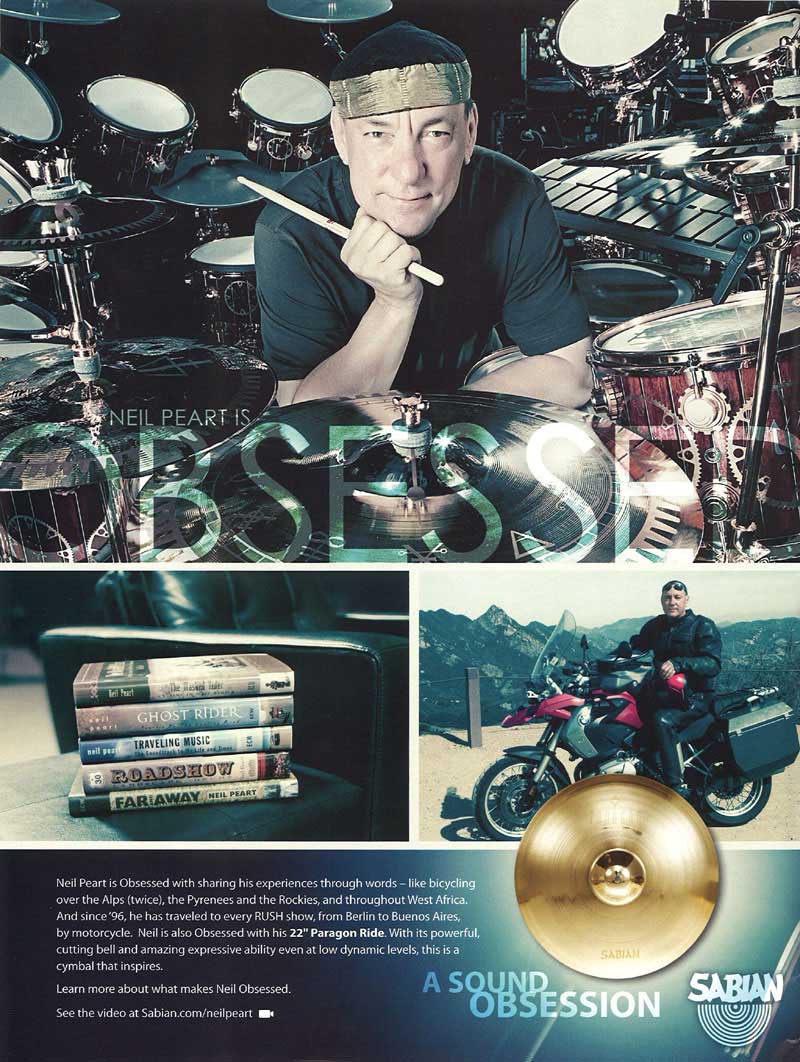

Given their collective age and status, Rush could rest on their laurels and do what many older rock legends do: periodically show up for an award show, play a tune, and then go home. But Rush has never done what most bands do. In 2010 and 2011, Rush did something very few aging rock bands do: They recorded a full-length studio album. (Rush's last studio album was 2007's Snakes & Arrows.) The latest offering, Clockwork Angels, is an ambitious concept album filled with 12 original songs that show Rush's three members performing at least as good, if not better, than ever. If that weren't enough, Peart (who doubles as Rush's lyricist and is an author of several books) co-wrote a Clockwork Angels novel with science fiction author Kevin J. Anderson. The novel is based on Peart's story and lyrics.

Rush will support the Clockwork Angels album with a U.S. tour that begins in September 2012, followed by a 2013 European tour. In July 2012, we caught up with Peart at DW's Drum Channel studios in Oxnard, California, as he rehearsed in preparation for the upcoming tour. Peart graciously offered us a rare opportunity to have a master class with the master himself.

REHEARSING TO REHEARSE

Although Peart has played drums for nearly 47 years, "practicing" drums remains one his favorite things "because it's so free of responsibilities and consequence." To prepare for a Rush tour, Peart begins rehearsing by himself for several weeks before he ever rehearses with his bandmates. "Geddy always jokes that I'm the only musician he knows that rehearses to rehearse ... But I do love that, the feeling of it even without an audience. It's just between me and those drums."

PEART'S WARMUP REGIMEN

Peart has no particular warmup routine before playing the drums on any given day. His warmup is more of a long-term process where "yesterday was the warm-up for today." According to Peart, "About four months before I start rehearsing my drum parts, I start working on the physical side of things," with heavy workouts three times a week that include "cardio, stretches, and yoga." While yoga helps keep Peart's muscles "supple" to protect him from injury, his workout regimen also includes weight training and long-distance swimming.

Because of Peart's "physical devotion" to himself as an "athlete," he has managed to avoid injury. "The essence of good fitness is building up strength around all your potential vulnerabilities ... I've always worked on shoulder work, for example, and I think that protects from shoulder injury because all the surrounding muscles are that much stronger, and the joints. I don't have elbow trouble or [trouble in] the surrounding areas because I take care to exercise the areas around them and build up that general level of stamina and fitness." To achieve these goals, Peart focuses on maximizing "reps and not weight." Still, he admits, "nothing prepares you for drumming but drumming. The impact. I do play so hard because I like the sound and feel of that, and that's part of what I have evolved into as a player."

MASTER PLAYER = MASTER STUDENT

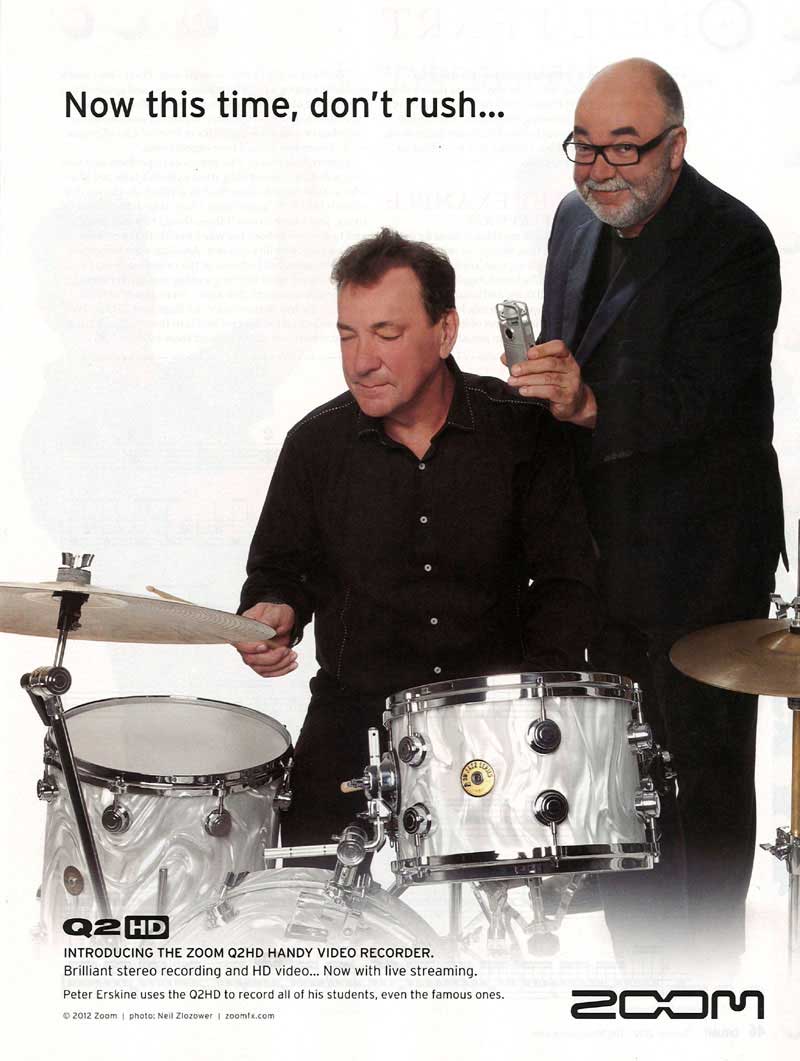

Despite his legendary status and phenomenal playing abilities, Peart has remained humble enough to "surrender" to a few great teachers over the years. In the '90s, for example, Peart felt his playing had become a bit stiff. He loosened up through studies with the late Freddie Gruber, who passed away in 2011. Of Gruber, Peart says, "I'm still being so much nurtured by the directions that he pointed me." Peart is not alone in this regard. Gruber's students comprise a who's who of drummers, including Dave Weckl, Steve Smith, Adam Nussbaum, and Peter Erskine - the esteemed jazz drummer with whom Peart studied in 2008. Peart chose Erskine based on recommendations from bassist Jeff Berlin, Don Lombardi (founder of DW Drums), "and the community of drummers around here that I love so much.

"We thought Peter would be good, and Peter had studied with Freddie, so he knew where I was coming from. I went to Peter mainly to upgrade. I said to him the first day, 'You know, as far as I'm concerned you're a surgeon, I'm a butcher.'

"He said, 'You're not a butcher.'

"I said, 'Yeah, I'm a good butcher, but I'd like to get more surgery into it.'"

With Erskine, Peart had clear goals. "Groove playing is absolutely what I wanted to go toward - smoothness, improvisation." Erskine had Peart practice simple quarter-notes and other exercises with a programmed metronome that would click for two bars and then go silent for two bars. "Every day, I'd pick a very slow tempo and a fast one." For Peart, playing a slow tempo for two bars "is a long time ... I was just going on faith that it was worth doing, and it was kind of enjoyable, too. I always say that for six months I played nothing but hi-hat, but it never got boring because I wasn't just doing time exercises. I was playing ... I would be doing all kinds of syncopations on hi-hat and exploring all rhythmic things, at the same time making them fall into perfect time." The fruition of Peart's studies with Gruber and then Erskine can be heard throughout Clockwork Angels. Peart considers the album the "culmination of what I always wished I could play like, and sound like and feel like."

RECORDING CLOCKWORK ANGELS

Rush recorded the album in Nashville and Toronto in 2010 and 2011 with producer Nick Raskulinecz (Foo Fighters, Evanescence, Marilyn Manson, Deftones, Velvet Revolver) - who also produced Snakes & Arrows. For Clockwork Angels, Peart recorded to guide tracks consisting of guitar, bass, and vocals. "When we first worked with Nick Raskulinecz on Snakes & Arrows, he was determined that we should be in the studio [all] playing together." Not so this time around.

"What the three of us have always known is it doesn't make any difference. We play to each other no matter what. So in the case of the sessions in Toronto, for example, Geddy and I were still writing when I started recording drum parts. So it was just Nick and me in the studio, and I'm playing along with the guide track."

Peart describes himself as an historically "compositional" player who "always orchestrated every detail of every drum part and played it over and over again until I learned it all intuitively without having to count." However, Clockwork Angels represents an evolution for Peart. This time, he employed a more improvisational approach.

"The determination to become more improvisational, to become more groove-orientated - the dirty-greasy groove I call it - it's a combination I wanted to have." Thus, for this latest recording, Peart says he would "play a song a few times myself and see what would work and then I'd call Nick in and we'd start recording." Of Raskulinecz, Peart says, "He's so enthusiastic that we had a ball, you know, just working. Nick's full of suggestions and crazy ideas - some of which I would never dream of putting into a song."

"CARAVAN"

EXAMINING PEART'S APPROACH TO ODD TIME SIGNATURES

Rush has always had an affinity for odd time signatures and syncopated groupings - both elements that remain prominent in the first song on their new album, "Caravan." While Geddy Lee sings, "The Caravan thunders onward," the song propels forward with bars of four, six, six, four, six, four, four, four, and five - many of which are punctuated by syncopated hits.

This is no simple chorus. When Peart hears it played back to him, he chuckles. "That's what my bandmates give me to work with." He elaborates, "They drop beats or add beats any place that they think a phrase is too long. A lot of it goes by the vocal phrasing, and that's what they're thinking." Nevertheless, even with a song like this, Peart doesn't count out bars. He learns these complex passages as musical phrases. "I do really stitch phrases together," which is why "sometimes it takes me a long time to learn the song, because I don't like to fragment it. I like to learn it as a phrase of music ... I keep note in my head of single, double - you know, the anomalies of the pattern." That this process takes a bit longer is sometimes quite amusing to Peart's bandmates. "They laugh at me when I'm working on learning it - shaking my fists at them. Ha ha ha. What's giving me fits is what they made."

"CLOCKWORK ANGELS"

HEMIOLA EFFECT

The album's third song and title track repeatedly shifts between bars of four subdivided by triplets, which Peart refers to as "a rolling four." Then, in what can best be described as a hemiola effect (i.e., three-over-two), the subdivisions of the triplets become the eighth-note pulse for bars of six. That is, a bar of four has the same duration as a bar of six. Peart navigates these rhythmic shifts from four to six while maintaining a powerful groove throughout. How did he come up with the idea to shift from four to six? Peart's reply, "I think the music demands that response."

In particular, "Clockwork Angels" is a song Alex Lifeson brought in as a demo with much of the sections already in place. As soon as Peart heard it, he knew, "I want to play to that, because it's something we had rarely done." Still, even with Peart's exceptional ability to play complicated parts, the time shifts in "Clockwork Angels" proved challenging. For this reason, in one transition from four to six, Peart can be heard clicking his sticks on beats 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Peart initially expected the stick clicks would be edited out of the final recording, but they remain because they sound good. Still, even with the song's rhythmic shifts, Peart's approach is more about phrasing and "inflection" than counting subdivisions. "I'm thinking lilt, honestly - I'm not conscious of the six and four difference."

THE DIRTY GREASY GROOVE

Rush's latest album is more than just a bunch of odd time signatures and groupings. There's plenty of the 4/4 "dirty-greasy groove" that Peart has worked so hard to develop. Two such examples can be found in the album's fifth and sixth tracks: "Carnies" and "Halo Effect." Both tracks feature Peart playing heavy rock grooves with a snare backbeat on 2 and 4 supported by syncopated bass drum patterns. We couldn't resist the cliché bass drum technique question: Heel up or heel down? Peart's response, "It's all heel up and a lot of force on the bass drum."

Yet another grooving 4/4 beat can be found on the album's 11th track, "Wish Them Well." The song begins with Peart playing the snare on all four beats.

As it turns out, Peart initially came up with this pattern without realizing its remarkable similarity to the groove on Sly And The Family Stone's "Dance To The Music." His bandmates pointed this similarity out to him, and it became a bit of a running joke. Peart admits, "All my earliest bands were R&B, and we played all that kind of stuff. So I expect that it's a direct influence."

"Wish Them Well" quickly shifts away from Peart's Motown-influenced groove and incorporates many different patterns throughout, making this song the "hardest" on the album. "There's nothing particularly hard about it technically," according to Peart, but getting all the feels, dynamics, and rhythmic shifts just right was "very difficult."

"SEVEN CITIES OF GOLD"

A NEW TAKE ON A CLASSIC RIFF

The album's seventh track finds Peart playing with what can best be described as an eighth-note feel with a hint of triplet to it. Although the song is quite modern, Peart's phrasing evokes the feel of some old big band drummers. According to Peart, "We weren't going to play [the song] live, but we started getting so much feedback from friends and fans that we realized it's going to be more popular than we expected."

At about five minutes in, "Seven Cities Of Gold" includes a fill that, when isolated, sounds reminiscent of a Gene Krupa or early Buddy Rich fill. (A devoted Buddy Rich fan, Peart produced and played on two Burning For Buddy tribute albums.) When we pointed out to Peart that his fill sounds similar to something one of his idols may have played, he seemed surprised, yet pleased. "It's where the beats lie, yeah. I get what you're saying exactly, and its very interesting because it's deceptively complicated."

Aside from its unique feel, this particular fill includes a "new trick" Peart has been working on - essentially, a modified version of the classic snare, tom, floor tom, bass drum lick. Peart varies this drumming staple by playing a crash cymbal with the bass drum. "I thought, 'What would happen if I did a triplet down to the bass drum and got a crash cymbal at the same time, or a splash?' The left hand is hitting the crash cymbal with the right foot on the bass drum. So that was a new technique. That's why I used it a few times in the album." Peart jokes, "I try never to repeat myself unless it's something I consider mine or it's new."

"HEADLONG FLIGHT"

IMPROVISATIONAL SOLOING

About 20 seconds into "Headlong Flight," Peart drives the band with a few drum corps-style snare drum riffs. "I have to go back to traditional grip for that because I learned all the rudiments that way."

At about 4:34, "Headlong Flight" culminates with Peart soloing through a swift flurry of sixteenth-notes - this time played with matched grip - that start with just snare but eventually incorporate the toms. Peart improvised this solo during the recording process. The band ultimately changed the arrangement to accommodate the drum solo.

"THE GARDEN"

THE DUAL ROLE OF DRUMMER AND LYRICIST

Clockwork Angels closes with a beautiful ballad called "The Garden." During the first half of the song, the drums remain silent while Geddy Lee sings Peart's rather contemplative lyrics including, for example, "The measure of a life is a measure of love and respect. So hard to earn, so easily burned." Does Peart calibrate his drum parts (in this case, by not playing at all) so that the listener will focus on his lyrics? Not quite. Peart's choice to not play drums on the first part of "The Garden" was all "about dynamics."

On a more general level, Peart follows the mantra that "a song is a vocal with instrumental accompaniment." Thus, Peart tries to "stay out of the way" when there's singing. Alternatively, Peart frames lyrics by "punching them up rhythmically. I love knowing the lyrics as a drummer because then I know where the vocal parts are going to be, and where syllables could be. I think I do a lot of that on this album. I think I always have."

TEACHING BY EXAMPLE

PRACTICING TO PERFORM

After graciously sitting down and speaking with us for over an hour, Peart did something that, despite his verbal eloquence, was perhaps more inspiring than anything he said: He played through the entire Clockwork Angels album from start to finish. Was this a thrill to see and hear? Absolutely. And not just because Peart played flawlessly, but because he performed the entire album with the sort of intensity and focus that one would expect to see at an actual Rush concert. "Perform" is the operative word here. Peart views much of Rush's catalog as "performance pieces" and spoke of the importance of a "performance mindset." Moreover, Peart concedes that even to this day, he can feel anxiousness or apprehension on show days. "It's in front of a lot of people with expectations, and I have expectations."

Clearly, this is a man who practices to perform and who feels a dedication and obligation to Rush's fans. All of us who as fans reap the benefit of that effort. As the master himself puts it, "The privilege I have is to do this for a living, and I have to do all those things to maximize that and to feel good about the way I handle that privilege - it's a responsibility in a way. And that's not only true of performance but in terms of the values we bring to everything we do in the songwriting and the arranging and the album covers. You know, every aspect of what we do - the live performance is a huge part of that. It's sustained us all these years and into these difficult times - that reputation that was built show by show."

Technical Tech: Lorne Wheaton

-Andrew Lentz

It's one thing to be a drum tech, quite another to be Neil Peart's drum tech. Lorne Wheaton has been with the Rush drummer for 14 years by his count and the job has only gotten tougher. Actually that's not quite true. "This kit is pretty much unchanged [from the Snakes & Arrows] one," Wheaton says. "It just has more bling on it."

But with 20 individual acoustic and electronic drums, 18 cymbals, a rotating riser, and a jungle of hardware to navigate on the steam punk-themed setup, the tech's attention can't waver for a second. "Neil is surrounded by the kit. It's not a case of where I can slip in there like I can with other drummers who play smaller kits," says Wheaton from the band's Toronto rehearsal space. "So when we break a snare head, he plays something else till we get to the end of the song, then he darts out of the kit, I jump in, switch the head, and then he jumps back on. That's the only way we can do it."

The ever-modest Wheaton credits Peart's technique for making head breakage less of an issue. "Ever since Neil studied with Freddie Gruber, he's learned to not play through a drum[head], where so many guys don't know any better," he says. "And he hits close to the hardest of any drummer I've ever worked with in 40 years."

Wheaton actually met Peart back in 1975 when the drummer first joined the band. Before that, he helped bassist/singer Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and original Rush drummer John Rutsey with their gear when they played Toronto coffeehouses on weekends. Later on, Wheaton was working with Max Webster, a huge Canadian rock act at the time. As Rush got bigger they jumped on tours with Max Webster, who also shared management with Rush, and, one thing led to another.

Though the Rush gig is full-time today, Wheaton freelances for other drummers when he can but he's had to let Keith Carlock and other plumb assignments go. In the '80s, he worked for a Journey-era Steve Smith, Alex Van Halen, and the touring drummers for Elton John and Robert Palmer. "I've done every job in rock and roll history, it's just that the drums stuck with me, and I got good at it, because I worked with some pretty amazing players," Wheaton says. "Steve Smith was the one that taught me how to tune correctly, and you know, just taking on things like that from certain drummers that I have worked with in the past really helped me and made me just stick with doing the drums."

Like any tech worth his lug ratchet, Lorne always knows what Peart needs before Peart does. They're both on the same in-ear systems and his station is back-left of the soundman. "We have very good eye contact," he adds. "And reading lips of course is one thing that you should learn how to do. Yelling [through the in-ears] gets a little old after awhile. So if a sample is too loud I'll get through to the monitor guy before Neil turns around to give me that look."