Gearing Up For The Road

Neil peart writes about his preparations for Rush's Clockwork Angels tour, launching in September, 2012

By Neil Peart, DW Edge, Issue #10 (2012-2013)

During the mixing of our Clockwork Angels album in January, 2012, Alex and Geddy and I started making plans for the upcoming tour. The first show would not be until September, but after thirty-eight years as a touring band our musical and visual presentations have grown ever more elaborate. The staging, lighting, and effects are enhanced by rear-screen films that lend much drama and comedy, and these ambitious productions take time to prepare.

Similarly, our live show is always highly demanding physically, as we, and our audiences, naturally tend to prefer our most energetic and hard-hitting songs for the concert stage. As the one who has to do that hard hitting, my physical state also requires some preparation. The ideal timing for me is when tour rehearsals follow a winter season of cross-country skiing and snowshoeing, or a summer of swimming and rowing. Those are natural and enjoyable ways to build one's stamina.

However, the seasons did not so converge this time. I knew I would be facing the most physically demanding Rush tour ever, and I would be turning sixty as the tour got underway. So in February, while we were still mixing, I began visiting my local Y three times a week, and continued that fairly religiously for the next four months.

A twenty-minute bicycle ride across town, with my workout gear stuffed into a backpack, is a decent warm-up. Changing at the lockers, I trade the helmet for a bandana, to keep the sweat out of my eyes (the same purpose as the hats I wear while drumming). My first ritual is a thirty-minute session on the cross-training machine, where I ease into something like the rhythm of cross-country skiing (though without the pretty setting). Keeping a fast, steady pace against a fairly high resistance, I raise my heart-rate to near my recommended maximum, and keep it there.

A row of those machines, along with treadmills and other types of ellipticals, overlooks the pool, and I often seem to be there when a geriatric water aerobics class is underway. It is not exciting to watch. I just keep pumping, and think my thoughts. Some people like listening to music while they exercise, but that has never worked for me. It's the same with motorcycling and skiing - some like music along for the ride, but I feel that those activities, like music appreciation, are "exclusive" states of mind, wanting no distractions. The only activity I combine with music is driving, because long trips by car are clearly made for listening to music. For me, exercise is an act of will, and not conducive to listening, reading, or creative thinking. So the time passes slowly. On the cross-trainer, I watch the red LEDs displaying time, distance, heart rate, calories burned, and level of resistance, and rarely go as long as a minute without checking the clock's achingly slow progress. I count down each fraction of a minute, and each fraction of the thirty minutes. "That's one fifth...that's one third..."

One time I got into trying to see how many sevens I could post on the screens (I think I got up to six). Suffice to say, it's painfully tedious. It takes a huge effort of will to get me there, and to push me through my routine. But it works.

One morning I was grumbling about going to the Y and my wife, Carrie, said, "But you love the Y!"

I could only stare at her in disbelief. How can a guy be so misunderstood? I make myself go there, and feel good for having done it - physically and "morally" - but I do not love it. Quite the contrary. I told Carrie, "If there were a pill I could take that made me feel the way I do after exercising, I would take that pill instead."

After thirty minutes I am well pumped and sweated, and I go to the mats for a program of yoga and calisthenics. Back in 2000, when I first moved to Los Angeles, I combined my Y workouts with yoga classes several times a week, and I believe the effect was enduring, keeping me balanced and flexible and preventing injury.

Since then I have incorporated the most useful poses and transitions into my own workouts. Standing on the mat, I do a series of neck and shoulder rolls, then work through the standing poses of the Sun Salutations, holding each pose for a count of twenty Mississippis. I especially like one of the Warrior poses, standing on one foot (gaze fixed on a distant point) with the other leg held back by its matching hand and stretching everything in that direction. Triangle is nice too. Lunges not so much - but, they feel...worthwhile. Then Downward Dog into Plank, and Upward Dog, each for that count of twenty Old Man Rivers, three times around - a flow of motion and pose called a vinyasa. (Lately I avoid pushups, as I do heavy weights, because they expose weaknesses - like a long-ago fall while skiing that remains vulnerable to over-exertion of my left shoulder). Then a few sitting stretches, all adding up to about twenty minutes.

Next, bent-knee situps on the board, inclined upward. I think twenty-five or so is good (because I've had enough by then).

My brother, Danny, is a personal trainer by profession, and over the years I have often consulted him about my workouts. With the weight machines, Danny counseled me to alternate muscle groups, so I'll do leg presses, bicep curls and tricep presses, leg curls, chest presses, leg lifts, and high-lat pulldowns. I do twenty reps of each, and for me, the appropriate weights have gravitated to 50, 70, and 90 pounds, depending on the muscle group. In the free-weight room, I do twenty chest flys with 15-pound dumbbells on an inclined bench.

Then comes a cooling reward of sorts - a long swim. If it were summer at the lake, and swimming and rowing my only workouts, I would row around the lake - about three miles - then swim up the shore to the next dock and back for a mile. But in the gym, after all that other sweaty exertion, a quarter-mile swim - fourteen laps of front crawl, two of breast stroke - is ample, and relatively pleasant.

It is unlucky that my bicycle ride home is all uphill - albeit gentle. I had the same situation when I lived in Toronto, and wished it were reversed. But at least the grocery store is on the way home, because another important aspect of fitness is diet, of course. Being the meal-planner, grocery shopper, and cook in our house (Chef Bubba is a working homemaker), our meals always offer a healthy assortment of nutrients. Lots of fish and chicken, steamed vegetables in multiple colors, and a comforting carbohydrate. I also believe in a daily multivitamin as a supplement (and single malt whisky, when the day's work is done).

From February until June I maintained that regimen, then on June 25th I started my drum rehearsals at the Drum Channel studio with my tech, Lorne "Gump" Wheaton. Geddy once joked that I was the only musician he knew who "rehearsed to rehearse," but I like to be prepared - and as we'll see, I need the workout. Gump and I would have three-and-a-half weeks to work on the songs, smooth out any technological problems, and dream up some new solo ideas. This is my favorite part of the touring process because I begin the day at home with my family, then have a challenging and satisfying hard day's work, and end up at home cooking the family dinner and sleeping in my own bed. And it includes one of the world's best commutes, fifty miles up the Pacific Coast Highway and back every day. You really cannot beat that.

During those months between, Alex, Geddy, and I exchanged many emails on the subject of the setlist - what new songs we would play, and which old ones we wanted to either keep or resurrect. Gump made me playlists of the proposed sets, pulling together the recorded versions of the songs for me to play along with. For the first few days we had the band's longtime programmer, Jim Burgess, on hand to set up the sampling arrays for the new and old songs, and to provide me with some new soundscapes for my solo.

Our friendly neighborhood Roland man, Drew, dropped off a set of the new V-Drums, the TD-30, for me to try. They were set up beside my main kit, and I gradually worked my way through the presets, looking for useful sounds or setups, and admiring the new level of dynamic sensitivity Roland has achieved with them.

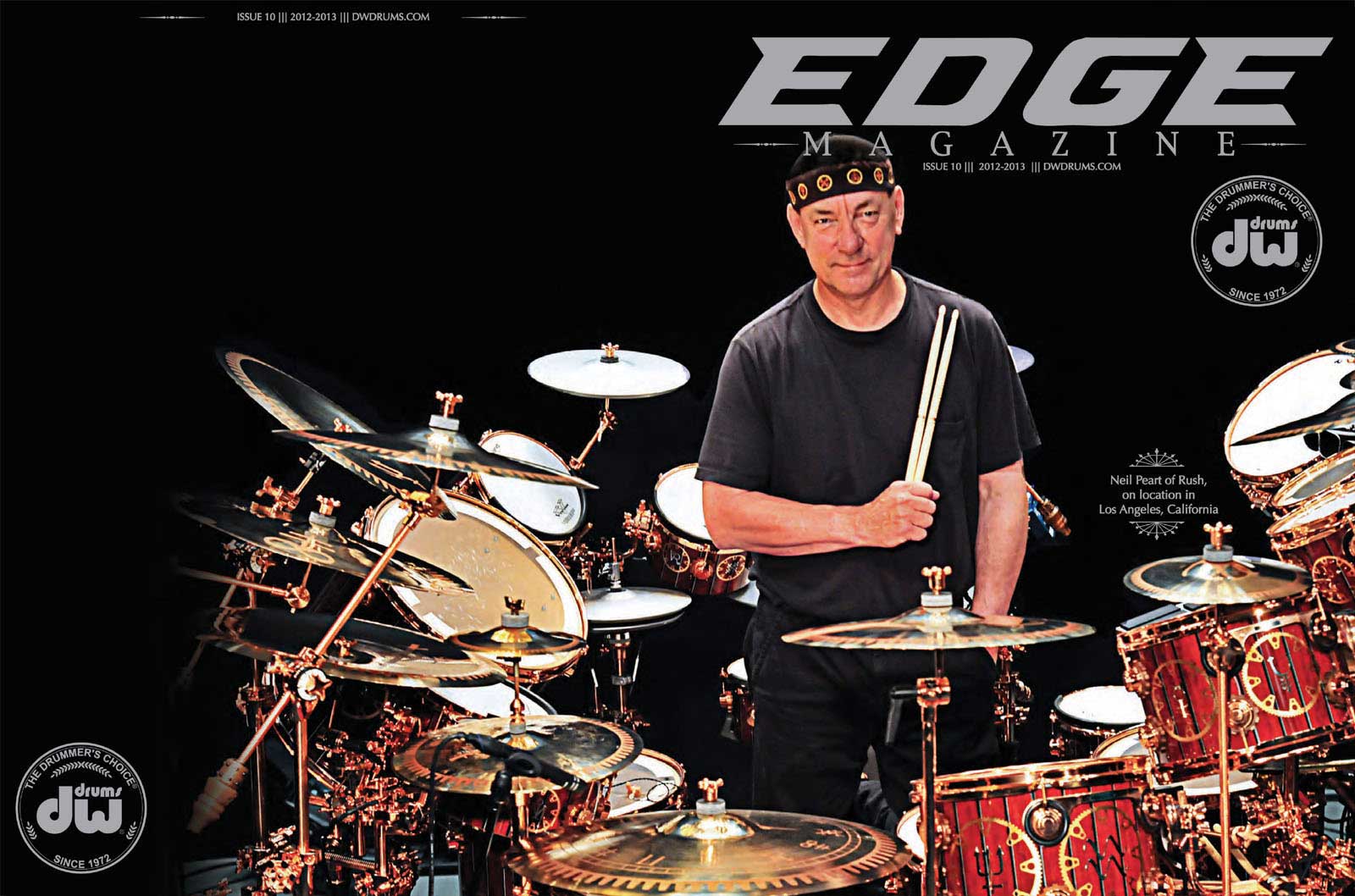

The main kit would be the same one I used for the Time Machine tour - the custom DW drums and Sabian cymbals - because, like that tour, the visual design was already built upon the Clockwork Angels steampunk theme. The album had been recorded with those drums (except the first two songs, recorded earlier on the Snakes and Arrows kit). Gump had spent a few days tearing it down and "restoring" it, and it looked and sounded as amazing as ever.

After such a long period of conditioning, I came in physically strong, but the only real training for drumming is drumming. See, it's all that hitting. Irresistible force strikes immovable object and that...a few thousand times.

In professional athletics this approach is called sport-specific training. Cyclists have to cycle and runners have to run. However, it remains true that all of the advance fitness work I did gave me the foundation to build on.

But during that first week of hard drumming, each night I went home aching all over, and woke up feeling even worse. But, as I always say, it's okay if I hurt everywhere, and not in one specific place. Not my back, or shoulder, or knee, but "from my nose to my toes."

Still, it's pain.

But it's necessary. The thing is, I like to hit the drums hard - for the primitive physical satisfaction of it, but mostly for the sound. For example, my backbeat on the snare is almost always full-force across the head and the rim, and I like to hit the toms hard for both definition and a slight detuning effect under hard impact that gives a "throatier" tone.

By the second week, the fatiguing nature of that trauma began to subside a little (though it never stops, really, for the remainder of the tour). I enjoyed relearning some songs from the mid-'80s we hadn't played for many years, like "Grand Designs," "Territories," "Middletown Dreams," and "Manhattan Project" and I could tell they were going to sound better than the records (because we play better now than we did back then). But it soon became clear to me that the proposed sets were way too long. Typically, we like to play a one-hour first set, take a twenty-minute intermission (before which Geddy always makes an announcement along the lines of, "We have to take a break - 'cause we're about a hundred"), then play another hour and thirty or forty minutes.

Gump and I could tell the two setlists I was playing to would add up to much more than that, and we would need to drop at least four songs. However, there were no obvious candidates, and when I mentioned this reality to Alex and Geddy, the three of us couldn't agree on dropping any. So I suggested something different for us: putting together two shows, Show A and Show B, that would alternate four different songs each night. In the past we had always preferred a fixed format for the setlist, and when confronted with only one or two songs in excess, we would either knuckle down and play them, or drop them for time constraints. This time, somehow the idea seemed more attractive to us when it was bigger (as it should).

It did mean having to learn that many more songs, and work them out musically, technically, and production-wise, but it seemed worthwhile - even just because it was different.

I faced a similar dilemma with my solo. In the recent past I had always performed a long solo, around nine minutes, somewhere in the middle of the second set. But...during the mixing of Clockwork Angels, our co-producer, Nick Raskulinecz, an irrepressible "enabler," insisted that I had to do my solo out of the drum break in "Headlong Flight." It happened that that song would appear around the middle of the second set, but - íJesu Christo! - "Headlong Flight" is a fast-paced seven-minute song, in the middle of a fast-paced hour-long performance of the Clockwork Angels songs, with another thirty or forty minutes still to go. Plus, coming out of that drum break I will still need to drive through a long guitar solo, another verse, bridge, and a double chorus, all at a fast tempo.

To say the least, it was daunting.

But...once again I applied some "polyrhythmic thinking."

What if I did two shorter solos, one in each set?

Ooh, yes - that had possibilities.

I described the idea in an email to my estimable teacher, Peter Erskine, as well as reporting on an important observation I began to have in the latter days of these rehearsals:

This time my former marathon-length solo will be divided into two - in the first set, an old-school, all-acoustic venture with classic rudiments and solo stylings, then in the second set, a more textural, electronic, and melodic outing.

And...both of them will start out completely improvised (I say "start out" because inevitably you fall into themes and patterns you like, but that's okay-and within the "spirit" of exploration).

So that's huge.

Also, I had the realization in the past week or so, as the playing started to come together, that these days, "I am playing the way I always wanted to play."

Meaning that for all these 47 years I have been working toward this combination of technique, power, and feel - "chops and groove." That's a nice feeling.

Shame it took so long! But...

Of course it's not really a "shame" - that's just how long it took. As another estimable teacher, Freddie Gruber, used to say before his passing in 2011, "It is what it is." I always insisted to both Freddie and Peter that I was a slow learner, but a good student, because I would practice and keep trying - even if it took forty-seven years.

During these rehearsals, I found that when I played along with the old songs we hadn't performed for a long time, like when I went into the upbeat ride patterns of "Grand Designs," it felt the way I wanted that part to feel back in 1985, but had only "approximated" it. Or when I played the half-time sections of a new song like "The Anarchist," I could physically see myself leaning back and away, playing at full force yet comfortably sinking into the groove of it - just "naturally."

When I'm rehearsing on my own that way, I know I'm starting to get somewhere when I have to start changing my sweaty clothes two or three times a day. In those three-and-a-half weeks, I also dropped at least ten pounds. (Obvious business opportunity: "Do you want to lose weight and tone your entire body - from your nose to your toes? Sign up now for the fabulous new, Bubba Drum Workout!" It would be a counterpoint to another weight loss program that claims to stop insanity, only this one would be called, with reference to the upcoming tour, "Start the insanity!")

Putting together a show like this one will be is a grand adventure, no question. I will never be jaded about that. But like some Victorian explorer planning an expedition to Africa or Antarctica, the undertaking requires a great deal of advance thinking and preparation, a lot of people in our support crew (some navigating without maps), and a goodly amount of adaptability. No doubt there will be suffering, too.

Right off the bat I will be away from home for more than two months straight, with band and production rehearsals in Toronto, and the first leg of the tour. The family will visit from time to time, but still - that is a long exile from one's everyday life. Nearly forty years of such a nomadic existence has adapted me to being separated from my loved ones, and taught me not to dwell on the sad fact of it, but those at home do not share that "partitioning." Carrie now becomes a single parent for the next five months. Three-year-old Olivia has had most of a year with Daddy being around, and now she finds his absence unsettling - and upsetting. As I have remarked before, I can endure missing Olivia, but I can't stand her missing me.

For myself, there will be nights I won't want to "face the music" - won't feel able to go out there and drive myself that hard. When I'll be sore and tired, maybe ill, and always homesick.

But those are not complaints - just part of the price we pay for the privilege of doing what we always wanted to do.

A joke my father loved when I was a boy has always stayed with me - the one about the man banging his head against a brick wall, and when he is asked why, he replies, "Because it feels so good when I stop."

Touring can be like that. Or like old Sisyphus, who was sentenced to an eternity of pushing a boulder to the top of a hill, only to have it roll down to the bottom again.

But there are those nights when everything goes just right - when the three of us lock into a musical symbiosis that transcends our earthbound humanity and sweeps the audience into a momentary spell. That is the timeless magic of live performance.

And there are the days off, when my motorcycle will carry me down remote back roads through natural splendor, shades of history, encounters with friendly strangers, and every sort of weather. These other kinds of grand adventure keep me stimulated and inspired through the passing shows, and the passing years.

But the biggest reward of all is being able to make a simple statement that has taken me forty-seven years to earn:

"The way I play now is the way I have always wanted to play."

Gearing Up Neil Peart for the Road

By Juels Thomas

If you're really paying attention at a Rush show, you might actually catch a glimpse of the covert technician on stage, just to Neil's left, behind a rack of electronics and blinking lights. Lorne Wheaton has been Neil Peart's invaluable gear guy, respected confidant, and trusted friend for far too many years to count. I sat down with Mr. Wheaton while he was at the DW factory to discuss just what it takes to prepare for a touring machine of this magnitude.

Juels Thomas: What was your first Tech gig?

Lorne Wheaton: Technically, it goes back to when I would help with bands in high school. One of those bands happened to be Rush, with the original drummer, John Rutsey. I would volunteer to help them at school dances or coffee houses. It was part of the high school deal on the weekends to try and keep kids off the street. So I used to volunteer because I really liked music. But my first real gig, like actually getting a paycheck, was probably with a band called, Goddo. It was a three-piece band, just about to break out and start playing clubs. I was part of that three-man crew, basically getting $100 a week. I would say my first real tour of any real size was with the band, Max Webster. We were supporting Rush because they had the same management company, and by this point Neil had joined the band (Rush). That's when I started really gettIng serious about it.

What's the biggest lesson you've learned?

To be a team-player, really. You know, you don't survive long if you go out there and you're just seeing in tunnelvision. The whole idea is to get the gig up and running and happening on time. And if you have to kick in with the lighting company or whatever, you pitch in. I remember doing that in the old days when I was with Journey and we would show up at some venues very late, for whatever reason. I can't remember why, but it was basically everybody in there putting the lighting rig together so we could get everything up on time. You're there to make the show happen. Whether you're the drum tech, Production Manager, lighting guy, or audio boy, everybody has to be there to get the job done.

So, it sounds like it was mostly on-the-job training for you. Did you ever take any music business or production classes to prepare you for this life?

Nope, it was all on-the-job training. I was lucky enough to work with and around people who are some of the best in the world. Still to this day! And I basically became the drum tech that I am just by learning, going along, being open for suggestions and paying attention.

What's the most important thing for a drum tech to master?

You know, first and foremost, you treat the drum kit like it's your own. I was lucky enough to work with Steve Smith in '83. He actually taught me how to tune drums correctly. Before that, I was just tweaking them and not really having any idea what I was doing. Aside from, you know, just thinking I knew what I was doing. He actually took time to teach me stuff. Often, you'll run across drummers and drum techs who can't tune properly. So, I think that's the most important thing: have a good ear and learn how to tune a drum correctly.

Do you play drums or any other instruments?

I wouldn't consider myself a drummer. I can play the drums, but compared to some of the guys I've worked with over the years, I don't come close. So you sit back and you enjoy the talent that you're working with. I don't really have a whole lot of interest in being a drummer. Yeah, guitar techs usually are guItar players. Keyboard techs are usually keyboard players. You don't necessarily have to be a drummer to be a drum tech, but obviously it helps. Sometimes you'll get on tours where the audio boys would like to have somebody playing the instruments in a band-fashion, especially if the actual artists don't like to do soundchecks. I can play enough to be that guy, but Rush are there for the soundcheck and they do it every day.

Do you make yourself an actual checklist of what you need to bring and do before the tour?

Yes. Obviously, you have to stock up on things like sticks. And my man, Garrison (at DW), is so helpful with us that even if I gap on something and have to call up for a last-second request, he's so all over it! I feel privileged to be able to deal with people like that. At the same time, I try to make sure my memory still works. I'll look at how many dates, because that's how you base what you need for backup stuff. Even though Neil's not hard on the drum set. As hard as he plays, he doesn't break a lot of stuff. So that's saying a lot for the manufacturers, as well. Since he worked with Freddy Gruber with drum lessons, it's amazing how much differently he approaches the drumset and his playing ability. The heads last a hell of a lot longer with him hitting them as hard as they possibly can be hit versus somebody else, or even versus himself before he had these Freddy Gruber instructions. It really does save drumheads and I don't change them half as much as I used to.

Are there any tools in your rig that you can't live without?

Probably my screw gun. I use it for tension rods. That cuts the job to a quarter of the time. Also, a ratchet driver because there are a few moving pieces on the kit that I have to make sure are nice and tight.

It's obvious that Neil trusts your expertise implicitly. How much input do you have when designing a new kit?

I'm probably his worst critic [laughs]. I've been with him long enough to be able to throw in my two cents, but we don't change a lot of things. He likes to keep everything pretty much the same, even when we're building new drum sets. We have to build boards that all the hardware screws into and I just template one board to the other. We throw all the hardware into exactly the same place. He doesn't like to complicate it too much.

What's the most challenging part of this upcoming tour for you?

Challenging? It's always a challenge because you're dealing with technology, and you're dealing with things that can blow up. Just spinning the drum riser, something bad can happen because we have all of the cabling underneath it. So, you know, you just deal with everything as it comes to you. We've never been stumped by any challenges. We've always been able to get through somehow. It's a little bit more difficult replacing snare drums or whatever on this drum set because you can't really get in there like you can on a four-piece kit. Neil, and only Neil, fits in there. So he basically has to jump off and I get up there, obviously, at the end of a song. We've pretty much mastered it. Neil is so good with something like that. If something breaks, he keeps his head; he doesn't freak out and he knows it's going to be taken care of.

Lastly, how did you get your nickname?

Well, it was back in the late '70s, I guess it would be, when I was with Max Webster and we were doing a lot of touring (with Rush). Geddy was the one who came up with it. There was a goaltender for the Montreal Canadiens named, Lorne "Gump" Worsley. And since my name is Lorne, Geddy just started calling me, "Hey, Gump!" It has nothing to do with Forrest Gump (the movie). And it's probably gonna stick forever too, but I don't mind it. There are worse nicknames to have than Gump.

Actually, when you consider all the saves Lorne makes on the job, being named after a goaltender is pretty fitting. And that's obviously why Neil relies on "Gump" to hold down the defense every night.