Mastery and Mystery

Neil Peart's Foreword to Rhythmic Composition: Featuring the Music of Porcupine Tree by Gavin Harrison

March 1, 2014, transcribed by Mark Rosenthal

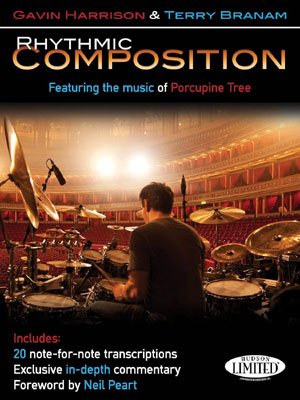

Rhythmic Composition: Featuring the Music of Porcupine Tree

By Gavin Harrison

Foreword written by Neil Peart

Published March 1, 2014 by Hudson Music, 128 pages, ISBN-10 1480365734

Calling Gavin Harrison "a great drummer" seems insufficient, even a case of "damning with faint praise." These days plenty of guys, and some girls, can demonstrate amazing technical prowess and speed on a drumset. Instead, I would call Gavin a great musician. His formidable technique and deeply analytical approach to drumset-playing are always focused on a simple purpose: serving the song.

His discography is dizzying in its variety, clearly representing a player who is able to be sympathetic in a great many disparate styles. He would never disrupt a vocalist's phrasing, or disturb a soloist's spotlight, yet he will always energize them - feed in currents of rhythmic electricity that elevate the whole, not just the drum part.

My introduction to Gavin's drumming was on a sampler CD made for me in the early 2000s by my dear friend Matt Scannell, from Vertical Horizon. From time to time Matt used to make me a playlist of music he had encountered that he thought was ... worth my attention. "You may not love it," he would stress, but he thought it seemed important to know about. I understood, and listened accordingly.

One of those CDs included a couple of tracks from Porcupine Tree's early masterpiece, In Absentia (2002), namely "Trains" and "The Sound of Muzak."

Well. Of course I know there is no way two songs can begin to hint at the breadth of Gavin's virtuosity, but I have to say - those two drum tracks offer a hell of a start!

The timekeeping in "Trains" gracefully smoothes over what could be a jagged combination of rhythms, while also planting strategic crash cymbals to help "orient" the listener. The fills toward the end are ingenious, not only musically, or even technically, but as pure listening excitement - taking the listener out to the edge of comprehension, seemingly the edge of control, across the time and straight through the middle of it. Yet they deliver us right back to the perfect "one" - feeling as though we have been on a carnival ride.

In contrast, the groove-making on "The Sound of Muzak" applies a more laid-back attitude - still intricate, meticulous, and intensely musical, but with a more relaxed feel. The listener is led "comfortably" through a complex rhythmic landscape with well-defined directional signals and milestones. The transitional fills are richly percussive and melodic - a combination of tuning and touch that is the hallmark of a deeply sensitive player.

Later, after hearing more of Porcupine Tree's music, and enjoying it - appreciating it - very much, I watched some of Gavin's instructional material. Hearing him expound on the way he worked, I was fairly astonished to learn that he had arrived at some of these "conclusions" by means that seemed entirely alien to me. Hearing the assemblage of his fiery fills and intricate accompaniments, I would think, "Yes - if I could play like that, that is how I would play."

But when I heard Gavin explain the thinking, the tools, the "machinery" that had led him to these expressions, I was kind of shocked. Onscreen, he would demonstrate some ridiculously complicated pattern, then say something like, "Now I will displace that rhythm by a sixteenth note."

"Ha ha," I would think, funny joke, right? But did he not proceed to play exactly that? (Near as I could tell, anyway - I never was good at maths.)

That observation alone was profound to me. The music Gavin created seemed entirely "relatable," even "organic" - constructed from a seemingly natural feel for rhythmic subdivisions, dynamics, controlled time feels (sometimes relaxed, other times aggressive), tension and release, techniques like triplet-feel fills slashing across straight-time passages - the "tools of the trade" for a master drummer. However, behind all that, the means Gavin had used to develop those ideas were completely foreign, completely opaque to me.

And isn't that wonderful?

Nothing wrong with "painting by numbers," that's for sure ("whatever gets you back to 'one"), but I have always worked more by trial-and-error, thinking of phrases in a more "conversational" way. Yet I believe I at least aim for the same style of expression and energetic punctuation that Gavin delivers with such seemingly effortless poise. As mountaineers would express it, there are "many routes to the summit."

But what's most important in the context of Gavin's drumming is that you don't need to be aware of any of that to have your pulse raised - to be inspired by his excellent example. You don't need to know the recipe to enjoy the meal, or know the formula to feel good from the medicine.

A poet in ancient Rome said, "If the art is concealed, it succeeds."

That principle not only reflects the previous analysis, but leads to another illumination - how subtly integrated Gavin's drum parts are with the orchestration.

Of course, Porcupine Tree is not the only "stage" on which Gavin has excelled. His studio work, as mentioned, is wide ranging and vast. The touring work, too - Level 42, for example, certainly a demanding rhythm section to join, following the sublime "pocket" and highly musical flourishes of Phil Gould (not to mention the phenomenal Gary Husband), interlocking with the powerful virtuosity of Mark King.

And more recently, to have been found worthy to play in an elite organization like King Crimson. What a heritage of drummers in that band! From the brilliant and groundbreaking Michael Giles, one of my own earliest and biggest influences, through lan Wallace, Bill Bruford, and Pat Mastellotto, and now Gavin will be working on new material with the latest lineup of that legendarily inventive ensemble.

So there will be more drumming excitement to look forward to from Gavin Harrison, and I for one will be listening with interest, and a little bemusement.

Maybe I should have paid more attention in math class?