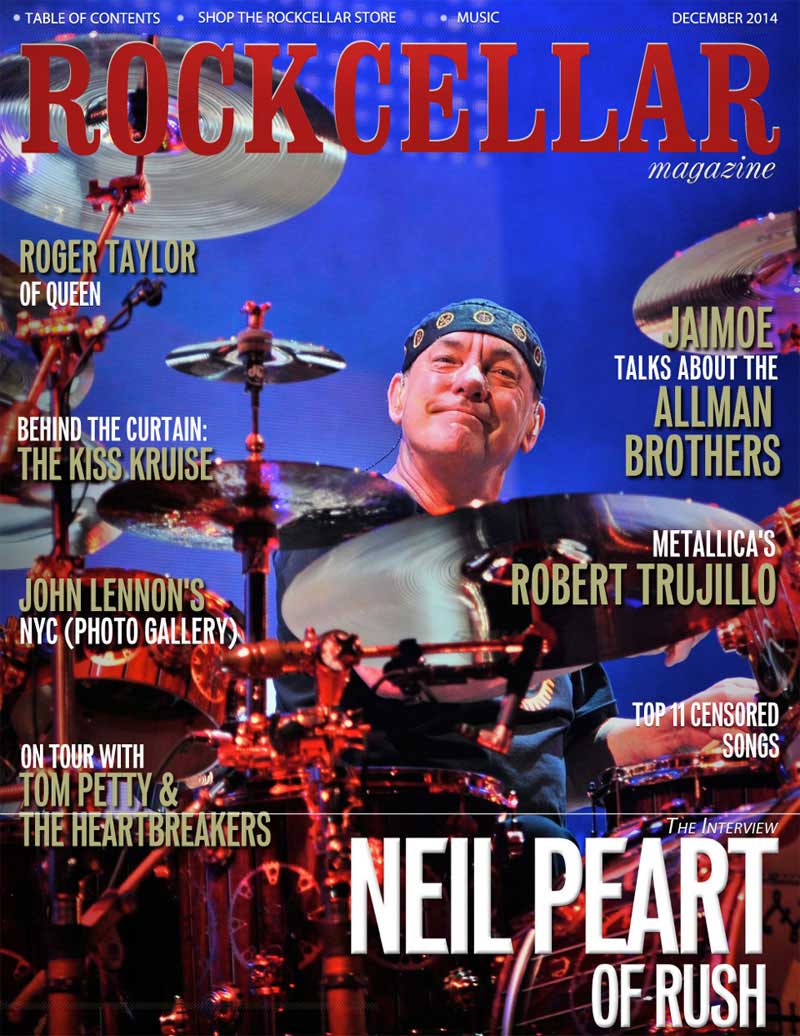

Neil Peart of Rush: The World's Audience

By Marshall Ward, Rock Cellar, December 2014

Neil Peart is widely regarded as one of the greatest - if not the greatest - drummers in rock history. But the stickman for genre-defining Canadian prog-rockers Rush does not carry himself like a rock star, nor does he define himself by the trappings of fame.

Away from the stage, he prefers a life of quiet contemplation, good conversation, and the creative outlet of writing.

He grants very few interviews, but made an exception for Rock Cellar Magazine to discuss the superficiality of stardom, the joys of anonymity, and the meditative joys of being an explorer, a writer, and being what he calls "the world's audience."

First off, thank you for granting us an interview. You don't give many.

Ah well, you're very welcome. Thank you so much in return.

In your new book Far and Near: On Days Like These, you write that "Magic exists, but it often requires some planning."

Yes, and the planning aspect is often underrated, at least if not dismissed, like inspiration is just supposed to happen to you. And I always loved a Picasso quote: "Inspiration exists, but it has to find us working." Now that's so obvious and yet so prosaic and unromantic, you know some people would say, 'oh no inspiration has to strike you like lighting,' and I say no often times you have to really dig, and the mining metaphor definitely applies. You have to dig for it and sometimes what I go through in words and trying to outline something, I'll try different points of view until finally I go, yes that's it.

Is that also the case with songwriting?

Oh yes, songwriting is a perfect microcosm for this because it's maybe 200 words but I'll labor for, oh, three days typically, all day long for three days over that. And I'll go through a kind of an arc, where at first there's a hope that I might be able to find something, convey it, and share it. And then I get caught up in the technicality of it and then I become discouraged about it and think, oh this is never going to work.

And I can remember times when I'd be on my way into the third day of struggling with a song and going 'ah I might as well give this up, I'm just wasting my time', and then bingo, I fiddle this around and this around, and do something and then I can see that it's going to work. Not that it's finished, the moment of triumph for me isn't when it's finished, it's when I see that it's going to work. And then of course that inspiration drives you with pleasure to go on and make it work, as it were.

Another songwriting insight just occurred to me, Tom Cochrane and I were talking about that one time, where we love to mention specific places, and I mentioned a song of his that has a line like "Can you remember the trip we took, In the Malibu to the west coast, We drove through a rainbow upon Rogers Pass." And Tom's response was, well I figured everybody has a Rogers Pass, and bingo, exactly.

And that's what you try to do is bring something alive that was important to you, and it should be universal. When you can take something from the particular to the universal, and let's face it that's a beautiful definition of what good songwriting often is, taking something that resonates deeply with you or even pains you deeply, and finding a way to make that universal so other people can find their pain or their joy in it.

That's an interesting thing I just thought of, yes, typically what you are trying to share is joy or pain, and if you can make yours ring with the listener or the reader then job done, I guess.

There's a chapter in your book titled "Where Words Fail, Music Speaks." Can you talk a bit about how difficult it can be to find the right words?

It's certainly a professional struggle in one way and interestingly it's a way I often entertain myself, say, on a long motorcycle ride or a hike or cross-country skiing even, by looking around me or thinking about something, or a feeling particularly, and saying how would I put this in words or how would I express this.

It's the perfect hobby I guess for a writer to have, looking around you and thinking in terms of, 'how would you convey this'? Because that's what writing as communication is about, conveying something to another person. And sharing it is one of the things I stress in my story, that I'm always wanting to share something that seems magical to me whether it's a landscape or an encounter with a person, or even sorrow basically.

Yes, in your new book you "share a little of the darkness as well as the light."

There are words and sometimes they have to be reduced to an essence that is so keen, and also when I think of people offering their sympathy to me, some of the most effective words ever were, "I don't know what to say but here's my heart". As simple as that.

And it's refining the language down. I've learned so many things, I learned like in a landscape how you convey that, you tell people what they need to know first which is usually maybe the weather, and maybe where you are. You describe what you're seeing and feeling about it from that vantage point. But it is always about how can I make the reader feel this experience the way that I do.

What motivates you to write?

The desire to share. And I love the tools of writing. I'll draw a drumming comparison there, drumming is about communication also and trying to move people, and the tools of it are the drums. And I have the same fascination for words as tools as I did since I was a child, from crossword puzzles to reading.

I'm an immensely absorbed reader. I just fall into other peoples' worlds, fictional or non-fictional very easily. So that makes me a good reader in that sense. The impulse to share, I think probably drives a lot of art. Not only because of the lonely voice crying out in the wilderness to be heard, but the desire to say "hey I love this, maybe you'll love this too".

And the simple way even I've defined our band's music, it sounds almost glib to say it, but it really is true, we make music we like and hope other people will like it too. And that's certainly my story writing ambition too, when something starts to get me excited then I want to convey that, and then that becomes being selective. And a trick I've learned lately is, if I find too many stories about a place, I know that can bog down a general reader where I tend to get very interested in a place after I've been there...I fall in love with it and then I learn all the history and want to share it.

But you can't possibly expect a reader to read all that. So I've learned now, I drop the germ of where a story is and I'll say "oh by the way this place I'm traveling through, there's a lot of great stories if you're interested in checking it out", and maybe give a couple examples and then other peoples' curiosity follow from there. And it's nice to know that it does I'll discover through the responses I get from my stories, usually from a circle of friends but also from strangers.

There's a great story about a stranger near the end of Far and Near...

Right, there's an account about how during my Roadshow book I was collecting national park passport stamps all over the place and making it kind of a quest between shows, to give me some excitement and adventure. So I was collecting all these passport stamps, and I got a letter from a guy in Georgia who was a motorcyclist and he couldn't go all over the country like I did, but he went to all of the state parks in Georgia.

He and his buddy made it a weekend quest that they would go out to all the state parks in Georgia and try to collect some kind of documentation from it. And he described they would go to the maintenance workers and ask them for a check-cancelling stamp or something to show that they had been to that state park, and that's the kind of inspiration - passing down and coming back to me - that does feel totally rewarding.

Some of the most endearing photos in Far and Near are of a Christmas tree in a living room, or an exterior shot of the quaint Swiss Inn Motel.

Well, yeah, and I always recount that one when I see a motel that I've stayed at and I see it's closed, or a gas station, or a little diner. And what strikes me is that it was someone's dream. Right? How many people dream of something immodest like that: 'I just want my own gas station. I just want my own restaurant. I just want to run a little hotel in a small town'.

That would be a great dream for a lot of people, after all, and then to see those wither away for one reason or another. It's like the sadness of being in a restaurant when you're the only person there and feeling bad for the people who own it.

I always do feel the human spirits of these places, however seemingly deserted, when I travel through the Mojave Desert for example. And the name desert doesn't describe the landscape or the weather, it means it's deserted by people.

But at the same time there are so many stories that have taken place nearly everywhere you travel around North America, and certainly across Canada, and around Europe, Africa, the stories that came alive to me there, and China.

The first adventure trip I ever took was a bicycle trip to China in the mid-'80s. And to be there in the midst of a society that was crumbling in a way that, I guess the way Eastern Europe did, and it hasn't fallen yet but at the time they were just coming out of the Maoist cultural revolution. And seeing the damage that had been done to the temples there and talking to people about what it was like to live through those times and seeing the fearful sorrow in them about that, and how guarded they spoke about it still 30 years later in that society.

And traveling through Africa too of course, the stories in the villages and the stories in the countries are endless and the wisdom is endless. And the oral history that I collected in Africa for example of little sayings that are so wise, and so much part of a different culture. Not a written culture but an oral culture, such that I would meet people who could recite hundreds of years of their village's history, verbatim. Or people who could speak six languages - not six dialects - but they would speak English-French in four different African languages because it's an oral tradition there, and their sense of time was inspiring and changed me forever.

But it's all about people's stories, and that's one thing that keeps coming back to me, wherever I travel is amazing things and people that have lived there, and what their lives were like. Even visiting Greek ruins, you know, I see the human side of it in all of those cases. What was it like to be a guy with a family living in a place like that?

Can you talk about your need for privacy as a writer?

Privacy became so important to me because I'm the observer, by temperament and by the kind of writing that I discovered I like to do. It depends on me being the observer, not being observed, and I am very much an audience and I've been lucky to have that privacy, and careful to protect that in terms of my identity and my prominence in the world.

I really do tend not to get recognized because I don't carry myself that way, I carry myself like someone who wants to listen to you, not someone who wants to show off. For myself certainly it's a private thing and it's an audience thing.

I like something the great DJ Jim Ladd, kind of a legendary Los Angeles old-time DJ in the truest sense said. He was talking about watching the documentary of us (Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage), and the three of us had dinner together and he said that I am Alex (Lifeson)'s perfect audience (laughs). And that stuck with me. I said I know I'm crying with laughter and choking to death at Alex because I am his audience.

And when I'm on stage I feel like the audience, honestly. I'm looking at people and reading their signs, looking at t-shirts or watching the way they behave, and I very much consider myself the observer even on stage in that context. But especially when I'm on my motorcycle or hiking and the world is coming to me in that sense.

And that's why traveling across the desert on a motorcycle is a very clear example of that, the world is coming at you. And you're observing it from an audience point of view. Even in a natural sense, I call myself the observer, the audience. I'm the world's audience.

Your co-author of the Clockwork Angels novel, Kevin J. Anderson told Rock Cellar Magazine how there's usually a crowd backstage cheering and whistling after a show when you and your band members are walking to the bus, and you'd say, "Why are they cheering? I'm just walking like everybody else? There's nothing special about the way I'm walking..."

Right (laughs), and those are the kind of things that really are alienating at first because you're doing the most ordinary thing in the world, right? You're walking home from work and people are making a fuss about it.

And that is totally unnatural, and this isn't a matter of complaint or anything, but on one of our live albums I think we said, "For all the friends we have already or any that we've lost, remember, we didn't change, everybody changed around us." And that's exactly what happens, and then adaptation is the only possible defense.

And my adaptation was to liberate myself. Even since the '80s I started carrying a bicycle on the bus and on days off I would travel around on my bicycle and on show days I'd ride around to the local art museums and the local parks, and be part of the world and talk to people. I've always said, on a bicycle you are always harmless and people will always talk to you. Especially in those days it was a less prevalent kind of transportation than it is now.

We would play in New York City or the Meadowlands Arena just outside New York City and I would ride up through Harlem and across the George Washington Bridge and never had the slightest bit of an unpleasant experience because it neutralizes you in a way on a bike. Or on a hike certainly, you make friends with everyone that you pass, when you're hiking in a national park. And motorcycling of course is anonymous and free, and those are two pretty great qualities actually that I can define for myself right now as a writer and as an observer.

To be anonymous and free makes me the kind of audience I need to be for the kind of stories I want to write and the kind of worlds I want to share with other people.

You've also been working with Kevin on a graphic novel project this year, right?

Yes, it's a graphic novel version of the Clockwork Angels story, and that's been just another tremendously rewarding thing to be a part of because it's a small group of people.

There were five of us working on it, a young artist from New Orleans, Nick Robles did the art, Kevin is the writer, he pretty much scripts the whole thing like a film director would do, and then I had my visions of what the different settings and characters should look like.

And we had two young editors from the comics company so the five of us were what I call the quorum, the smallest decision making body, and it's the size of a rock band. And I thought, yeah, everything should be decided by a rock band because it couldn't be democratic, it had to be by consensus. All of us had to agree that this was best for the story, for the book, for our visions of it and all that.

And it strikes me, no band could work as a democracy either because you would just have factions who would very soon hate each other. Like Canadian people, or American people, they become more and more polarized, that would be the circumstance.

How are decisions made in Rush?

Something I always say about a band of three, especially like us, is we can't be a democracy. You can't have two against one. It's never going to work it, has to be consensus. You have to keep working on something and then it goes back to something we talked about a little while earlier, you have to keep plugging away. We've had songs that the two of us like and the other one doesn't.

Well, we don't just stop there or throw it away or force the other one to accept it, we keep going until all of us like it and there's always a way to do that, to find that consensus.

And even in a book form I love working with editors. It is always a pleasurable experience for me because they are encouraging and you have the sense that all the little changes that you make together elevate the entire work so much. I always find that an absolutely inspiring and rewarding experience rather than grim, having to work with an editor wanting to change things.

Well, you could never survive in a band with that attitude of course, because everybody of course wants to change everything when you're in a band, especially if they are strong-willed artists of vision. But you want them to be that way.

And that reminds me, talking with solo artists in the past who have said to us they wish they could be in a band like ours, but inevitably they are often people who are too strong-willed that they can't collaborate with others or they've never found collaborators perhaps worthy of them, whatever. So they have to become solo artists as a result. But they would love to be in a band because it is totally the ideal situation, to encourage each other, inspire each other and make your own work better.

Have you always worked with an editor?

Yes, even on my initial stories, since I first started getting interested in prose writing actually. I even then would hire a freelance editor to help me learn and to go over my stuff and tell me what I could do better and what I was doing wrong, and so on. And I still do every single piece that I publish. Even on the internet I'm part of what they call the "slow blogger community", where I take just as much time with my stories there as if I was publishing them and work with an editor and work with a designer and carefully, carefully structure them and go over them to eliminate the errors.

And then the second stage of that was working with Jennifer Knoch at ECW Press and refining it even further and learning more. It's called critical enthusiasm, and it's the necessary quality they have to have because they can encourage you by saying, yes, I really like what you're doing and here's how I think you can do better. Well, no one can resist that (laughs).

I think when people work with other people they forget that simple courtesy, and it's the same way in our band, if somebody brings in an idea you don't just say, that sucks I hate it. Typically, someone brings an idea in and you say, ah okay, I see what you're going for, that could be great, how 'bout if...? And you offer something to make it better, not tear it down.

So for you, that's the essence of collaboration?

Yes, it has to be ego-free. And even the little collaboration on the graphic novel, I describe it was totally ego-free. All of us knew, and there was a reason for that though two, because we could trust that all of us had the same view in mind. Now, with a lot musicians, artists, probably writers too, you're getting conflicting opinions with different motivations, and they're saying, well this could be more commercial if you did this or that. Well that doesn't help the conversation, right? (laughs)

In writing, I'm not concerned about being commercial in the music or the prose writing, and I have a whole other aim in mind. And if I know the editor has that same aim, or in the studio that your producer has the same aim, or if somebody's trying to squeeze you into producing a single or a commercial piece of writing, then you have mixed motives and you can't trust them. So that's what works in the context of our band or what works for me in these other collaborative roles, working with Kevin for example.

Now we're at work on another series of stories from the Clockwork Angels universe because we didn't want to leave it, and there were so many incidental characters in the story that we wanted to know and tell their stories too. So even getting into the world of fiction like that with Kevin has been a rewarding collaboration that is always positive.

Did you grow up reading comic books?

I did. I just wrote a little afterward for the graphic novel actually saying when I was growing up in the '50s and '60s, if we were going on a family road trip I would be allowed to buy two new comic books, you know, from the drugstore rack. And what they meant to me in those days was, everything from the Disney ones to the superhero ones to Archie, Casper the Ghost, and most of all the, I think they're called Classics Illustrated, and they were like great works of literature put in comic books.

But that's how I got to know who Tom Sawyer was, and Huckleberry Finn, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. My first introduction to those was just that.

Do you enjoy revisiting both your first books and early Rush albums?

Well, with my first book, The Masked Rider, yes, I can still live with it. Musically, I'm more satisfied with more recent work and still enjoy contemplating it. I'm more forgiving now where I have emotional appreciation for the older works.

I remember at the time we made it, again our motives were always pure, so I can look at that now and I know we were trying our best. And at worst, I feel a smile rather than a twinge, because it's maybe an embarrassment of how naïve we were.

One way we describe it lately is we were young, foolish, brave, and fun. Which is a good combination. Those are the four qualities I recently described the way we were through the early years of our career (laughs).

How different are Canadians and Americans?

I've been living in the United States now for 14 years and traveled it extremely widely. Probably few people have traveled as many back roads as I have and I've come to love the place and the people, with all their faults. Are there differences between Canada and the United States? Of course there are, but America is what it is for a lot of reasons historically. There's nothing essentially different about the backgrounds of Canadians and Americans, but we have certainly developed our cultures in quite different ways. So yes there is a difference.

In the outro of your book, there's a quote by Mendelson Joe: "Every day is Thanksgiving."

Yes, and then I add, with a tinge of regret, "And every day is memorial day." I don't know if you've suffered losses, but those people we lose tend to be with you every day, so those two sayings can go together.

I can say, yes I've had my tragedies, and certainly regrets and sorrows but at the same time I love my life right now. That's the best I can do.

Another favorite quote of mine that's in the book is by Bob Dylan: "The highest point of art is to inspire." That is the most beautiful definition of the limitations of an artist, right, because so often much more is expected of you from people of a transformative nature. I also love another thing Bob Dylan said once when someone was grumbling about his success and all that, and his wealth, and how could he be a protest singer if he was wealthy?

And he said "for every dollar I've earned there's a pool of sweat on the floor". It's another one of those quotes that's like, yeah, so true.

I used that in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame thing too, the greatest gift is that, and I just mentioned it in context with the book. I close my book with that observation that my greatest satisfaction with the previous book was inspiring this guy to ride his motorcycle around Georgia. Maybe it's not a lot, but I think it is.