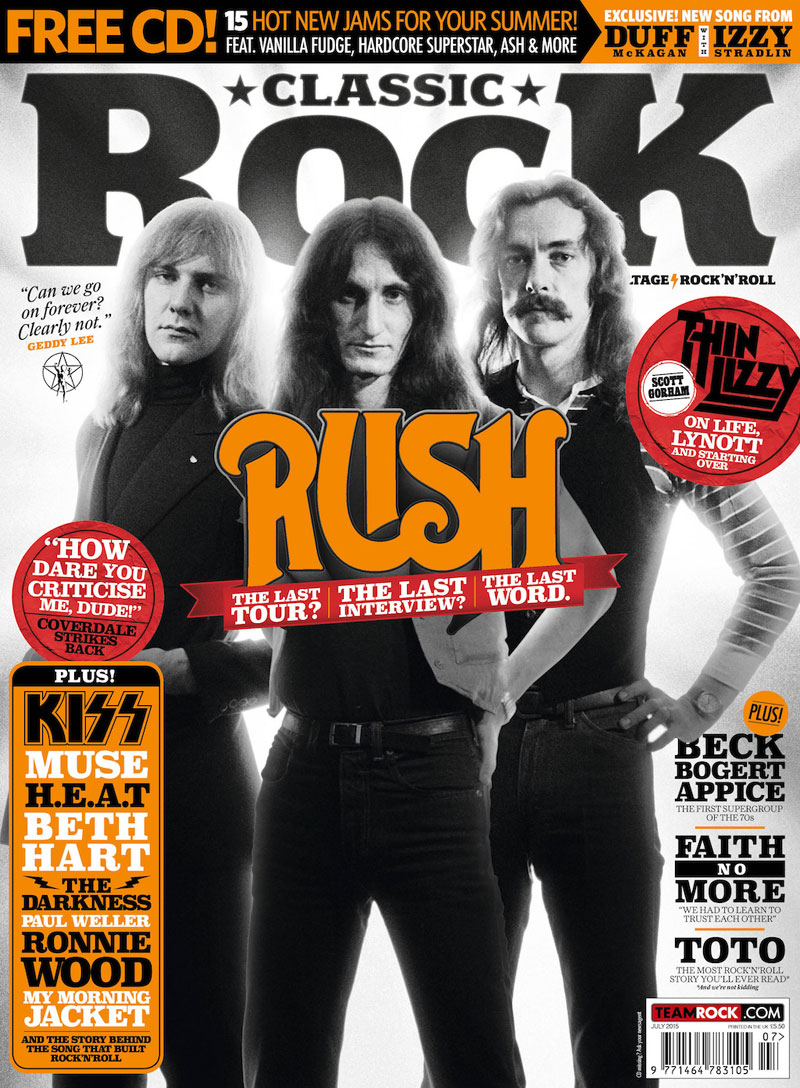

Everyone Loves Rush

After decades as the uncoolest band on the planet, everyone from Dave Grohl to Hollywood A-listers suddenly loves the Canadian prog-rock visionaries. So why are they thinking about retiring?

By Paul Elliott, Classic Rock #211, July 2015

It's in the last couple of years that he's noticed it happening: he's been a famous rock star for decades, but in these past two years he's found himself being recognised in public more frequently. Now it's a little easier, he says, to get a table in a fancy restaurant. Even so, Alex Lifeson is not entirely sure he likes this new level of fame: "It is a little uncomfortable for me."

As the guitarist in Rush, Lifeson is part of one of the most successful rock bands of all time. Since their formation in Toronto in 1968 they've sold more than 40 million albums. And yet, for much of the band's career, they have existed, as Lifeson puts it, "under the radar".

The three members of Rush - Lifeson, bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee and drummer/lyricist Neil Peart - have been playing together for 41 years now. Their brand of progressive hard rock and virtuoso musicianship - defined on breakthrough 1976 album 2112 and modernised on 1981 best-seller Moving Pictures - earned them a devoted following that has sustained them through the passing of punk rock and grunge and all that has followed. For many years, Rush have been known as The Biggest Cult Band In The World. Then the strangest thing happened: they got bigger. Rush were always a big band, but they are now bigger in a broader cultural context.

It started with the 2009 movie I Love You, Man, Lifeson says. In this "bromantic comedy" there's a scene in which its leading characters are seen rocking out at a Rush show and embarrassing a girlfriend with their word-perfect lip-synching and air drumming: so very Rush and their fans. Then in 2010 came the band's documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage, in which a cast of modern rock heroes such as Billy Corgan and Trent Reznor revealed themselves as Rush nerds.

And then, in 2013, came the induction of Rush into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame - at which their live performance was prefaced by the Foo Fighters playing the 2112 Overture in wigs and the kind of white satin robes that their heroes wore back in '76. And for Alex Lifeson (pictured below with Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl), that was the clincher. "The Hall Of Fame changed things," he says. "It's really given us a much higher profile."

The irony in all of this is that Rush have become more famous at the very point at which their career is in the first stages of winding down. The band's 2012 album Clockwork Angels was a huge success: No.1 in Canada, No.2 in the US, and widely acclaimed as a late-career masterpiece. This month, Rush head out on a 30-date US tour. But Peart has repeatedly stated that he is no longer willing to tour on a regular basis. He has a young daughter, and his priority is his family. He is also suffering from tendonitis. And he's not alone in feeling the wear and tear of age; Lifeson has arthritis. He says simply: "Let's face it, we're coming to the end of our career together."

On the eve of the US tour, it's Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee who speak to Classic Rock about the present, the past and the future of Rush. Neil Peart is unavailable for interview. He has rarely spoken publicly in the past 20 years, and the reason for this is well documented. In the late 90s, Peart's daughter Selena was killed in a road accident, and his first wife Jacqueline succumbed to cancer. In the aftermath, the band remained on hiatus for five years. Peart returned to Rush for the 2002 album Vapor Trails after he had remarried, but relinquished his role as the band's chief spokesman in order to protect his privacy.

Lifeson and Lee have a small window in which to talk. After four weeks of rehearsals in Los Angeles, where Peart now lives, Lifeson and Lee are at their homes in Toronto ahead of a week of full production rehearsals back in LA.

Lifeson speaks first, and for the most part he is in typically upbeat mood. He is a frank and funny interviewee. Speaking to Classic Rock in 2014, he revealed that he had used ecstasy during the 90s, and he is similarly candid when discussing the complex dynamic within Rush in 2015. He admits that in recent months he has considered leaving the band, but when he talks about this US tour he's buzzing. "The ticket sales went crazy right from the start," he says. "Some dates sold out in minutes, and it sent a message to us that something's going on."

Could this tour be the last for Rush?

We'll see. Right now the tour is what it is. Whether we add more dates, I think it all boils down to Neil, really. It's a very athletic endeavour for him to go on tour. He's sixty-two years old. Physically it's difficult. And it's the same for me.

Your arthritis - how bad is it?

I've had it for ten years, and this is the first time I'm really feeling it in my hands and my feet. That's the way it goes. But it's a lot harder for Neil. He's got tendonitis in his arm. To be honest, I don't know how he gets through playing the way he does, being in that sort of discomfort and pain. But he's a very stoic guy. He never complains.

But there's more to it than that. Neil has said many times that his first priority is his family, his young daughter.

I don't think that's something he even needs to talk about. I don't know if sometimes he says these things because he doesn't know how to come out and say it face-to-face to us that he doesn't want to do it any more, that he's tired of it, that he feels after forty years that's a pretty good run and that he shouldn't have to feel bad about not wanting to do it any more. He wants to spend more time at home and with his family. I get it. He's never been keen about touring. It's always a difficult thing for him.

Is Neil unhappy about doing this tour?

He was resistant to it until he started prepping and realised: hey, I can still play my drums pretty good! And then getting into rehearsals with us, there's that whole camaraderie that he really adores. So when he's back into the stream, he loves the swim.

Do you have similarly conflicting feelings?

The Clockwork Angels tour was pretty gruelling, as they're all becoming more gruelling as we're getting older. And then we had a year-and-a-half off. Having the time at home and disconnecting from being in a band, just being Al, hanging out with my grandkids, seeing my friends, all the things that people take for granted, it got me thinking: am I ready now to give it up? Can I be happy being away from it? And it really felt like I could be. Until we started to zero in on a tour. Once the machine got rolling I got swept up in it.

Where does Geddy stand on this?

Now, more than ever, Geddy wants to play. Whereas Neil probably would have quit years ago, if he didn't feel that he owed something to us.

What do you mean by that?

I think Neil knows that we're not ready for the end, and he doesn't want to ruin that for us. Keep in mind: we're like brothers. And we went through a terrible period with him in his life and supported him and he'll never forget that. I think he feels, as I would too, an obligation to us for having stood by him. So he's not willing to let that go. Maybe now he is. And I get it. It's not like, what a jerk, he doesn't want to do this any more? I get it.

All three of you seem very reluctant to have an official farewell tour. Why?

Partly because it's a cheesy thing to do, but also it puts you behind the eight ball if you do decide that you've made a mistake and you want to go back on the road. And we don't feel like this is really a farewell. I'd love to make another record. It's such a fun experience to make a record.

You feel confident there is another album in you?

Yeah, I think there is. I'm sure if we start coming up with some stuff, Neil would be right in there. He'd love that.

Going back to the very beginning, when you listen to the first Rush album what do you hear?

I hear so much promise, so much excitement. I remember those sessions vividly. I hear Led Zeppelin in it - who we adored. And I hear so much hope for the opportunity to do what we'd dreamt about doing for so many years.

When did you first feel like you'd made it?

We opened for the New York Dolls at the Victory Theater in Toronto in seventy-four. It was an old burlesque theatre, pretty run down and crappy, but to us it might as well have been Wembley.

Rush and the New York Dolls seems such a mismatch.

It was. That crowd was excited to see the New York Dolls; not so much a local heavy metal band. But it was exciting being around the Dolls. Watching them backstage it was all what you would expect. They were all drunk before they got on stage. They had girls back there. It was a whole rock'n'roll scene. We were typically Canadian and shy and stayed out of their way. I do recall, though, after that gig I was hitch-hiking home with a friend of mine, I had my guitar with me. This couple picked me up, and we were chatting, and they said they'd been to the Dolls show at the Victory and they said yeah, they were great, but the opening act, God, they sucked. They were chuckling, and the guy's girlfriend turned back and saw the guitar and saw me and her face just kind of froze. It was silent in the car, and I felt so crestfallen I said: "We'll get out at the next block, please." I got out of the car and I wanted to throw my guitar away. That was the first really bad review that we got [laughs].

Was Rush always a competitive band?

Maybe in the early days, when you were so full of piss and vinegar and so excited to play. You played with so many different bands on these two- or three-acts shows. Quite often it was competitive. You wanted to blow the other guy off the stage and be that much better. I remember we played with Heart once. This was very early, maybe 1975. It was at the Stanley Warner Theatre in Pittsburgh. There was so much talk about Heart and the Wilson sisters. We were really looking forward to meeting them. We were backstage, and Roger Fisher said to me: "We're gonna blow you guys off the stage tonight, you just watch." And I thought, wow, what a weird thing to say. But I think I played that much harder that night.

And Roger Fisher didn't win that battle?

I guess, in the long run, no.

Are there Rush albums that you look back at and are embarrassed by?

Often people ask me that about Caress Of Steel. But I listened to it not too long ago and I felt proud of that record. It sounds to me like a bunch of twenty-two-year-olds trying to make a big statement. And 'Caress Of Steel' is such a great title.

I thought so. Around 1980 I had 'Caress Of Steel' written on my school bag. People laughed at me.

People laughed at us, too. You were in good company.

Are there particular songs you wish you'd never recorded?

Tai Shan [from 1988's Hold Your Fire] was a little corny. We wanted to do something different, but maybe we had too much of a pseudo-Asian flavour to it. Maybe I should listen to it again. I don't think I've listened to it since we recorded it [laughs].

A pseudo-Asian flavour like the borderline racist intro to A Passage To Bangkok?

Well, A Passage To Bangkok had a bit more of a middle-Eastern, Kashmir bent to it. Tai Shan was specifically about an experience that Neil had in China, whereas Bangkok talks about an experience we had all over the place.

You mean smoking pot?

That certainly influenced those early records. Less so as the years went on, but it was never completely out of the picture. We always made sure the tour bus was well-stocked with potato chips and cakes and things [laughs].

It sounds as if you were smoking a lot up to and including Hemispheres.

Yes, right through to Hemispheres and a little bit beyond...maybe Clockwork Angels.

Really?

Oh, sure. But Geddy gave up all of that a long time ago. He's one of those really militant non-smokers. He leads a very clean lifestyle, although he does love his wine.

Unlike you, who got into ecstasy in the nineties. Did you tell Geddy and Neil they should try it?

I think Neil may have had one or two experiences with it, but I don't think he liked that particular feeling.

What about cocaine?

It's been so long now. There was a period in the late seventies and early eighties when we all sort of dabbled in that thing. But it's such an alienating drug. I remember every time I ever did it I hated it. I loved it for that moment, and then hated everything else about it. It wasn't good for conversation, friendship, anything.

And now you're just a smoker?

I'm a pretty regular smoker of a very small quantity, for therapeutic purposes. I find it helps with inflammation and pain. I have my medical card for my prescription here in Canada, where medical marijuana is legal. And if we get rid of the Conservative government and get the Liberals back in, they have a whole policy about the legalisation of marijuana that is realistic and makes sense.

Might the problem with legalising marijuana be that much of Canada would slow down to the pace of the first Black Sabbath album?

Ha ha. Yeah. But is that such a bad thing?

You've always been characterised as the joker in Rush. How would you describe Geddy and Neil?

They're both very funny guys, clever and smart. Geddy loves to learn about things, whether it's baseball or wine or vintage bass guitars. He loves to get inside a particular subject. And Neil is a strange cat. He's very bright, obviously, and thoughtful. But he's also very private and inward, very shy. You'd be surprised at how easily embarrassed he becomes in social scenes. He can be great at a dinner party, but in a larger group he'll be very, very, very uncomfortable, and he'll be in a corner, nursing his Scotch, waiting to get out of there.

Was Neil always so withdrawn, even before the events of the late nineties?

In the early years he probably did more interviews than Geddy and I did. In many ways he was the band's spokesman. Since that tragedy, he definitely did become much more private. He carries a lot of deep, deep scars from the things that have happened in his life. Most people who know what happened to him can't even process it. But I think in general our fans do respect his privacy and know where it's coming from. In this day and age, where nothing is private, it is a miracle that he has any privacy at all. A tragedy like that makes him more of a target.

In the late nineties, Neil said he was done with Rush. It was only in 2002 that you reunited and made the Vapor Trails album.

There's so much emotion in that record. That took a big chunk out of our lives - that was a year of, oh, so many difficult things. Every time I listen to that record it takes me back to when we were recording it and how Neil was doing, and how poorly he was playing when he first came in the studio, and how he rose from those ashes - we all did. We were all so tentative and hurting. That album, more than any other album, has left a mark on the three of us individually.

If the band had ended in the late nineties, what would you have done with your life?

It's so hard to speculate. I love art. Maybe I would have become a painter. Only last year I thought about taking a course at the Ontario College Of Art. It's been fantastic to play in this band my whole life, but there is so much more out there.

Had the band ever come close to breaking up before then?

Yes. In 1989 we'd done a long tour and were mixing the live record, A Show Of Hands. We were so deeply exhausted that it just wasn't fun any more. We wanted - all of us - to go our separate ways. It was nothing personal, just the pressure of work. Really, the stress and tension was tearing us apart. Fortunately we took a long break, and we came back renewed.

Being in this band for so long, what has it cost you on a personal level?

We were doing two hundred and fifty shows a year when my kids were young and when I should have been home with them. That's a sacrifice that we've all made. But now my kids are grown up and they're happy and content and proud of their dad. It's worked out okay.

Looking back at your career, what are you most proud of?

I'm going to be sixty-two this year, and I've been playing with these same two guys longer than just about any other band in the world. That's quite an accomplishment.

If you had to choose three albums to sum up the band's career, which ones would they be?

2112, Moving Pictures and Clockwork Angels. I think that would cap what we're about from beginning to end. Boy, that's two concept records.

Well, Kirk Hammett from Metallica did call you "the high priest of conceptual metal".

He was right! I knew he was a smart kid.

But, joking aside, when the end finally comes, how would you want Rush to be remembered?

Boy, how do you answer that without sounding kind of corny? I guess I want the legacy to be: they did it their way, and they were true to what they believed. We earned our independence from the music industry early on with 2112, and we've been free to do what we want. We were true to our art. I want to be remembered for that.

For Geddy Lee, being at home in Toronto for a few days between rehearsals is an opportunity to spend time with his family, and in particular his infant granddaughter. "Being grandparents is a new experience for my wife and I," he says. "It took us a month or so to get our heads around that fact. We were sort of in denial."

Currently, he divides his free time between Toronto and London, where he also has a home. When in Toronto, he and Lifeson are in frequent contact even when they're not working. Around once a week, Lee says, they get together for dinner, just the two of them. Lee, a connoisseur, always chooses the wine. In the past they used to play tennis together, but not so much since Lifeson developed arthritis.

It was in Toronto that Lee and Lifeson attended school together. Peart met them for the first time in 1974, when he auditioned for Rush as they sought to replace original drummer John Rutsey. In a sense, Peart has always been the odd man out. After joining Rush, he lived in Toronto for a few years but later moved out to the country. When he relocated to Los Angeles it had little impact on his relationship with Lee and Lifeson.

"Neil was never really accessible," Lee explains. "So the fact that he's in California now is not a huge thing to overcome. When we need to talk, we talk."

These days it's Lee who is driving Rush forward. He wants to tour more. If he gets his way, the band will return to the UK and mainland Europe in 2016. Whatever happens next, he says, will be dependent on how the other two guys are feeling after the US tour: "If everyone's really digging it, the way I think we will, then we might carry on."

Alex is struggling with arthritis, Neil with tendonitis. How are you holding up?

I'm fit as a fiddle. But for Alex the arthritis is not a small thing. Frankly, I'm a little surprised he talked to you about it. And really, if anything is going to mean that we can't tour any more like we used to, it's more than likely going to be the arthritis. Because that's something that will directly affect his ability to play. And if I was going out on stage and I could not play the way I want to play, or the way I have played in the past, there is no way I would want to do it; I would not want to go out there and be a shadow of my former self.

This is clearly something that worries you as much as it does him.

You know, it kind of hurts me to see him when he's having a bad day, physically. He's one of my oldest and dearest friends. And when he's been at rehearsal and he's not playing his best, it's not nice to see your friend suffer like that. This thing is in the back of his mind, and he's afraid of it.

Neil is more vocal about his reluctance to tour.

Well, Neil has a more complicated life than Alex and I do, let's face it. Our kids are grown up, it's much easier for us to tour. When my kids were the age that Neil's daughter is it was a much more difficult decision every time you walked out that door. What you also have to remember is what Neil has been through in the past. He's been to hell and back. And now he's got a second family that he's trying to do the right thing by. There's no one on earth that could blame him for that. It's a matter of him being able to juggle what he can do with the band, and what his family can deal with, and how he feels in his heart about all that. I completely understand that.

How do you deal with such a delicate issue?

It's an ongoing conversation; a difficult conversation, and one that we kept putting off before we got together for this tour. I think it's hard for Neil to bring up some of this stuff, because he knows that no matter what happens he doesn't want to feel like the guy who's pulling the plug. It's hard for him. And I accept that. But decisions have to be made. We have to get on with our lives. So that conversation was tough. But in the end we decided we would do a tour, and Neil was fine with that. Once he made that decision he was a hundred per cent there. There's one thing I want to make really clear: there is no bad guy in this scenario.

If Clockwork Angels turns out to be the last Rush album, could you live with that?

Oh yeah. I'm very proud of that record. It's certainly among our top three pieces of work.

How confident are you that you could make another?

Do I feel like we have the mojo to do more records? Absolutely. But I can't tell you that the other guys agree. I'm not a hundred per cent sure that Neil agrees, I'm pretty sure Alex agrees.

He does. You should ask him - I did.

Ha ha. Okay. What did he say?

He said he would love to make a new album. So there you go - I've helped you with that one.

Thanks, Paul!

It seems that everyone loves Rush now. Is that a strange feeling?

First of all, it's great. But yes, it is odd. The fact that more fans want to see us, and younger people are getting turned on to our music, that's a very cool thing. It's nice that people like us and feel okay about saying that out loud [laughs]. There's really no negative in this whole new acceptance of us.

Do you have any idea why this has happened?

It's hard to understand. Obviously longevity pays off. And I guess there's an amount of passion and authenticity that we bring to our brand of music that must also mean something in this day and age.

It's not just about the music. The documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage humanised the band.

That's true. The documentary is what Rush is: it's a story about three friends. And a lot of people liked that story. By making that movie, by allowing people in, it's shown a side of our personality that is appealing. The fact that we do get along so well, we do have a lot of fun and we love what we do, that has become kind of 'a thing', for lack of a better descriptor [laughs].

There are the caricatures of Rush: Alex as the joker, you the uber-nerd, Neil the professorial type.

There is certainly truth in all of that. The caricatures are a start.

And on a deep level?

I'd say that Alex is hot-blooded. If I put him in the context of Rush, he's the raw emotion in the band. He's the guy who's going to freak out first, the guy who's going to lose his temper. He's also very sweet and lovable. He's the guy in the band you want to hug most. He's so funny and so considerate, but he can also be very irrational.

And Neil?

Neil is surprisingly goofy. This is the thing most people don't realise about him. He's this big, unwieldy guy, and when he gets in his goofy mood, it's hilarious. The first day he pulled up for his audition, Alex and I thought he was the goofiest guy. We had no idea that lurking behind that goofiness was this professorial, serious man. We're all more than what we appear, obviously. Or less [laughs].

You stopped doing drugs a long time ago. Those two guys did not. Are you comfortable being around them when they're stoned?

If you hang around so long with people that love their weed, you get used to it. I'm just amazed at how good people are at functioning on that stuff.

You couldn't handle that shit?

That's why I stopped - because I became completely dysfunctional when I was high. I just couldn't stop talking. I couldn't stop pretending I was Woody Allen, or trying to take my pants off over my head. I kept trying to make people laugh, and it is easy and hard to make stoned people laugh. You'll say something and they'll laugh, and you'll say something else and the room gets really quiet and it's like, "Okay..."

Classic drug paranoia.

I was always okay when I was with the guys. What was hard for me was I'd go to my bunk on the bus and my brain would be going six hundred miles an hour. My problem is I can't stop over-thinking everything. It doesn't help me to have a stimulant like that. It aids my over-thinking. I prefer a glass of wine or two, that helps chill me out. That puts me in my happy place. I don't need to be high. I feel like I've been blessed with a natural sort of high-ness.

So when Alex told you about trying ecstasy you didn't feel like you were missing out?

Oh my God, I'm way beyond that. And I wouldn't want to be a witness to it. I don't want to be anywhere around that guy in that condition. The thought of it fills me with dread!

Are you embarrassed by any of the music that Rush have made?

Some of the early stuff makes me cringe a little. I hear a song and think: That was so Genesis-influenced. Like, what the fuck were we thinking? It's so derivative. And the long instrumental things that we were doing back in the seventies, some of it seems so pretentious.

Long, instrumental, pretentious songs - that's what I call 'proper Rush'.

Okay [laughs]. I can see that. I have friends, musician guys, who say to me all the time that after Hemispheres there was nothing else of interest to them. So when you make that statement it makes total sense to me. In their minds that was proper Rush. And you saw that kind of thing in our documentary. I loved the fact that Trent Reznor got more interested in us post-keyboards, yet [Rage Against The Machine bassist] Tim Commerford hated anything post-keyboards. That kind of says it all.

The pretentiousness in those early songs has a lot to do with the lyrics that Neil wrote. Perhaps most pretentious of all was Xanadu, its lyrics inspired by the Coleridge poem Kubla Khan.

'I have dined on honeydew' [laughs]. Try singing that! Try singing about Kubla Khan, for Christ's sake.

You pulled it off.

Oh yeah. I loved it! I was into it. But after a certain time, I guess you could say I became a little more objective about lyrics.

Were there lyrics of Neil's that you rejected outright?

Oh yeah, absolutely. Sometimes it just doesn't work, and I can't get behind it.

Did that cause problems between you and him?

In the early days it was harder. We were just becoming songwriting partners, and that was a rapport and a trust that took years to develop. But he's a remarkable songwriting partner, in the sense that he does not have the requisite ego that comes with the work.

In later years Neil has written some beautiful lyrics about the human condition, for songs such as Afterimage and The Pass. Is there a song that speaks to you more than any other on that deep level?

I like The Pass as well. It's one of my favourite lyrics. And I find The Garden, from Clockwork Angels, one of the most beautiful things he has written.

It's now forty-one years since the first Rush album was released. Back then, how big were you dreaming? Did you think you were going to be the new Led Zeppelin, or were you aiming a little lower - the next Budgie, perhaps?

Ha ha. Well, who dreams small? Nobody does that. Especially when you're young, you dream big. You wanna be the next big thing. You want to be the next Deep Purple. But really, you don't ever equate your meagre talent with your favourite bands. Especially with us being Canadians. We're far too modest for that leap of faith.

In all the years since then, have you ever thought about leaving the band?

No. Never. I can honestly say I have not one day ever thought about quitting.

You've dedicated your entire adult life to this band. Any regrets?

I wish I had not been so obsessed with the band when my son was young. I wish I had been more in the moment for him. So yeah, I do have regrets about the early part of his life. But my son and I are very close now. And when my daughter came around, fourteen years after my son was born, I made myself way more available to her. You live and learn, you know?

And if the band was to end soon - for all the reasons we've talked about - could you accept it with a sense of gratitude for what it has given you?

I'll be honest. I don't like the idea of it ending. But obviously the conversations of the last year have forced me to come to terms with mortality - mortality in the sense of the band. If there is a time when we become a non-functional creative unit, then it will be hard to move on to other things, but move on I will.

August 1, 2015 is the date on which Rush conclude their US tour, at the Forum in Los Angeles. Beyond that, the band's future remains undecided. During this tour the difficult conversations between the three band members will be continued. For now, only this much is certain: they have not yet reached the end of the road, but the end is in sight.

Geddy Lee says it is in his nature to be optimistic. Even so, he remains pragmatic. "Right now," he says, "I'm just trying to enjoy the ride. Can we go on forever? Clearly not. We don't know if this is the end. And if it is the end, it's going to happen in bits and pieces. If we can't go out and do a massive tour in the future because everyone can't agree on that, there's nothing to say we can't do another record or one-off shows here and there. That's the best way I can describe it."

And for Alex Lifeson, there are mixed emotions. After a lifetime spent on the road, Lifeson, like Neil Peart, wishes to devote more time to his family. But he is acutely aware that if the band is going to go out on a high, it has to happen soon.

"I want to know I can play as good as I always have, or at least close to that," he says. "I love it when people say: 'You've got to see these guys, they can really play.' I want Rush to always be that band. That's a legacy that I'd like to keep intact. That's what the essence of Rush is. It's these three guys that have always loved playing together. I know that we're coming close to the end, but I still have so much fun playing with those two guys. When time comes, it's going to be hard letting that go."

The bits of our interview with the Canadian prog legends that didn't make it into the magazine.

On the eve of a US tour that may be their last, Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson and bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee talk to Classic Rock in a wide-ranging interview covering their entire career. They discuss their greatest work - from their zinging, Zeppelin-influenced debut album through to epic masterpieces such as Xanadu and La Villa Strangiato and on to their 2012 concept album Clockwork Angels. They talk about the complexities in drummer Neil Peart's lyrics, the obsessive nature of their fans, and the good times and the bad times in their long history together. They also address the question that all Rush fans in the UK want answered: will they ever play here again? But first we take them back to 1974 and that first album, Rush.

When you think of the time when you made that record, what is the first thing that comes to mind?

Alex Lifeson: I remember how exciting it was to be in the studio - even thought we could barely afford it.

Geddy Lee: It was a great time for us, and there's some great raw stuff on that record. The first Rush album really stands up better in some ways than some of the later things.

That album was the only one the band made with drummer John Rutsey, who left Rush in 1974 and was replaced by Neil Peart. It's now seven years since John Rutsey died. How do you remember him?

Geddy: John was an odd gentleman. A difficult person, in the sense that he had a hard time dealing with himself. He was not a happy guy, and had demons that he wrestled with. And when you're that kind of person it's hard for you to deal with other people. There was a lot of conflict and secrecy in the band when John was in it. We couldn't really read him and he didn't really care to share that much with us. And when Alex and I started pushing the music in a new direction, he eventually said: "I can't get behind this." That was the end.

Alex: John left before the album was released in the United States. But he was part of this thing. He had the same dreams that we had.

In those early days, did you always believe that Rush would be successful?

Alex: I don't think we ever thought we would be big. The dreams we had then were of making more records and touring; playing in front of bigger audiences. We were playing high schools and bars. That was our world for six years. As a Canadian band your chances of getting a record deal were slim, and getting out of Canada even slimmer.

Geddy: We were never that kind of obnoxious band that said: "We're gonna be huge!" We just hoped we could be as good as bands we thought were good - Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple and Yes and Genesis. When we toured with Kiss in 1975 we couldn't believe we were playing in America and travelling around. It was all so new and exciting to us. And we honestly thought it was probably the last time this would ever happen to us, so we should enjoy it. I think I still have the keys to every hotel room from that tour. I kept them because I never thought I'd ever be in Lubbock, Texas again. And in fact I haven't been to Lubbock, Texas again.

For all the success that you've had since then, were there times when you felt that - outside of your core fan base - nobody gave a shit about Rush?

Geddy: Oh, there were lots of times in our career when we felt it was such an uphill struggle. Many years ago, before we did 2112 [in 1976], we thought we were going nowhere fast.

And later on?

Geddy: There were times when we didn't feel we were getting mass appeal, but it wasn't something we were looking for.

Alex: We've always been aware of the loyalty of our fan base. And it's shifted over the years, of course. In the eighties we lost some of the older fans from the seventies. And with all the stuff that's been happening in the past five or six years there's been another shift, with a whole new segment of younger fans plus all our older fans. There have been points where there's been less interest in general. But we continued to tour through those times and we've always done well touring.

The mid-nineties seemed to be a difficult time for Rush; the albums Counterparts and Test For Echo were widely ignored at a time when alternative rock had changed the musical landscape. Did you feel, deep down, that Rush had become irrelevant?

Alex: With every new era of music, whether it was punk or the whole Seattle scene in the nineties, it was supposed to have carried a nail for our coffin. But we've ploughed through those times. Yeah, there have been times when maybe in a broader sense we seemed irrelevant. But we've always managed to continue. And really, we never cared whether we were relevant or not.

Rush are a progressive rock band in the broadest sense; the music has constantly developed across the years.

Geddy: I think that's true. In a way, we've always been searching for a new us. That's been our curse and our blessing - we always think there's a better version of us to be done on the next record.

Alex: I don't think all our records are completely successful, from a creative standpoint. But we always tried with each record to do exactly what we wanted to do.

Geddy: And really, any criticism we've had was fair game for the time [laughs]. When you've been a band as long as we have, and been through the ups and downs we've been through, you take everything in its stride. We've made a lot of mistakes on record, but we've been able to learn from them and move forward. We've aged well because we've been able to apply the things we've learned. It's all part of evolution.

What are those mistakes you've made on record?

Geddy: I don't know if entire albums fall into that category, but certainly there are songs that I don't feel great about.

For example?

Geddy: Just recently I listened to the song Neurotica [from 1991's Roll The Bones) and I thought, what the fuck was that? It's just a strange tune. I feel we've had a very up-and-down career as songwriters, but one thing that's always held true is our honesty about what we're doing. Like it or not, this is what we are [laughs].

Certainly you're renowned as a group of virtuoso musicians. And if there is one Rush song, above all others, that captures you all playing at the top of your game, it has to be the classic La Villa Strangiato, the nine-minute instrumental tour de force from 1978's Hemispheres.

Alex: It absolutely is. It's epic. There are so many parts to that song, and everybody shines on it. My recollection is that it was only a few takes to record the song. In fact if you listen closely during the guitar solo you can hear the previous solo ghosting underneath. I remember us playing the whole song in one piece and then we dropped in for that solo.

There's another epic - Xanadu, from the previous album, A Farewell To Kings - that you also recorded in one take.

Alex: With Xanadu, we ran that down once to get the sound and levels, and then we hit 'record' and played the song and it was done. Pat Moran, the engineer on that record, was shocked. Seldom did a rock band do one take of a song that's eleven minutes long. He was blown away.

It was after those landmark albums of the late seventies that the modern Rush was born, with songs that were shorter and more direct. And from Neil Peart there was a new approach to lyrics, in which he ditched the fantasy and sci-fi themes of 2112, A Farewell To Kings and Hemispheres.

Alex: We just felt we were working to a formula that was a little stale. Hemispheres was really a difficult record to make. It was written in a key that was very difficult for Geddy to sing, in a really high register, the whole record. It was time to move on.

Geddy: For some of our fans, records like Hemispheres, that's their favourite Rush. And when we started changing and our songs got shorter and more tuneful we lost those fans.

The 1980 album Permanent Waves was really the bridge between the old Rush and the new Rush, the link between Hemispheres and the modern rock of 1981's Moving Pictures.

Geddy: Permanent Waves really is kind of a bridge album, and a hugely important record for us.

Alex: I don't know what it is about the chemistry between us, but I think without Hemispheres we wouldn't have gone to Permanent Waves the way we did. Permanent Waves was really a hybrid of Hemispheres and Moving Pictures. We still had some long tracks on there - Jacob's Ladder and Natural Science - but also shorter songs like The Spirit Of Radio and Free Will.

Which do you think is the unsung classic in the Rush catalogue? For some fans it's the 1984 album Grace Under Pressure.

Alex: Grace Under Pressure is a good choice. Signals is a bit like that too - overlooked because it came after Moving Pictures. Looking back, I think Grace Under Pressure suffered in production, but the songs are really strong and there's great diversity on that record. Counterparts is another one. There's a lot that I really like about that record. There's a feel about it, a tone and a mood.

Geddy: When we were doing Grace Under Pressure it was a pretty low time for us. We weren't sure of the kind of band we wanted to be. There was a lot of experimenting. And there was rejection from different producers that we'd hoped to work with - that was a bit of a reality sandwich we had to swallow [laughs]. We ended up pretty much producing that record on our own, and it was hard.

On the albums that followed Grace Under Pressure - Power Windows in in eighty-five and Hold Your Fire in eighty-seven - the band's sound became increasingly dominated by Geddy's use of synthesisers. How do you feel about those albums now?

Geddy: Those records were also experimental. Power Windows was a high note. That was a great record. Some of the work we did on Hold Your Fire was very positive, some of it less successful. So there were a lot of ups and downs in those years. But the cumulative body of work, the best from those years, stands up pretty well.

Alex, you've said in the past that you felt marginalised in thas period, your role as guitarist limited. You said you were frustrated. Were you also depressed?

Alex: Honestly, no. I've been fortunate that way. I've been down at times, yeah, because I've felt trapped or bored. But depressed? Not really. It's not in my nature.

Geddy: It was a difficult time for us. Alex was resistant, of course, because more and more keyboards were coming into the band.

Did that lead to arguments between you?

Geddy: I think it's more in our nature to quietly harbour resentments than to go on attack mode. But we had some pretty bold conversations, I'd say. All the cards were on the table.

Toto guitarist Steve Lukather says that his band used to fight over music. Did that happen with you?

Alex: I can't say we ever did. There was never a personal issue. If we had a disagreement over something, whether it was musical or otherwise, we always talked it out.

Is Rush is a genuine working democracy?

Alex: It always has been. And it wasn't just a majority that ruled, it had to be unanimous in any decision. So if two guys wanted to do something and one didn't, then you talked about it, you worked out the pros and cons, and at the end of it, if there was still that one that didn't want to do it, it didn't get done. It wasn't worth having the bitterness over some seemingly meaningless decision.

Is Neil equally open to discussion about the lyrics he writes?

Geddy: I am a fan of Neil's, and I love being a collaborator with him, because he is so objective and easy to work with. We'll be recording songs, and stumbling over a word or something, and if Neil is not in the studio we'll get him on the phone and discuss it. He'll even allow me to suggest lyrics - a word that might work well - and he'll accept it or he'll come up with a better one. He's really a pleasure to work with. With Neil there are no hissy fits, ever. And also, over the years he's become more and more sensitive about shaping the lyrics to make my job as a singer easier. He looks back at some of his lyrics from the past, the things he's given me to sing, and he doesn't know how I did it [laughs].

Alex: When it comes to lyrics, Geddy is very free with the scalpel. He does severe editing, because he wants to be able to know clearly what the idea of a song is. Ged's got a great sense of what the presentation of those lyrics needs to be for everyone to have an understanding of what's going on. Ged's got this way of paring it down to its essence. And it makes the delivery more convincing for him, and that's what he's all about. And Neil's really good about that.

Geddy: You focus on what works, not what doesn't work. And if it was ever something that meant a lot to him, we'd have to discuss it conceptually: why is it not working for me?

Have there been times when Neil has written a lyric that you don't understand?

Alex: His lyrics are not easy. A lot of times I have no idea what he's talking about [laughs].

A lot of people were baffled by the story Neil wrote for the Rush's 2012 concept album Clockwork Angels. Did you get it?

Alex: Oh, with Clockwork Angels I was probably more confused than ever.

Geddy: I understand it quite fine. I spent months working on those lyrics and discussing them with Neil. We went back and forth with some aspects of Clockwork Angels quite a lot, to make sure that it came off more universal and less overtly proggy.

Alex: Neil is so patient with that sort of thing. If I'd written a song and it was being dissected the way his lyrics are dissected, and then rewritten and rewritten, I don't think I could do it. Especially with ten or eleven songs on the record. I think I'd have strangled Ged. And then strangled myself.

If you were to pick one song to illustrate how great a lyricist Neil is, which would it be?

Geddy: I love Bravado, from the Roll The Bones album. That's a song in which very little was changed in the lyrics from its original inception to the final version.

Alex: I think The Pass is really beautiful. That was one of those songs that happened very quickly. Resist is another one. I love the lyrics in that song, they really speak.

As a Rush nerd of thirty-five years' standing, I'd say that this band, more than any other, brings out the geek in its fans.

Geddy: I think there's truth in that, for sure [laughs].

Do you understand why?

Alex: Maybe because we take it more seriously in one way. Maybe our music, and the lyrics, are geeky?

Maybe it's the detail in your work. There's so much of it to obsess over.

Geddy: The fans love detail. As we do. We put a lot of detail into our music and our album covers and the film and our live show. We try to have a lot of stuff to keep people amused and entertained.

Alex: There is certainly a lot of detail to obsess over [laughs]. It's not just shallow music to make you feel good, that's for sure! It's serious music. And I guess we've been doing it for so long, that is the label we've earned.

Rush are also, for many fans, a lifetime obsession - once you're in, there's no getting out again.

Geddy: Ha ha. Yeah, that's also very true.

Some fans - myself included - like to savour the moment whenever a clock ticks over to 21:12. The last time I did this, holding up my phone to show my wife as I declared: "It's Rush o'clock!", she rolled her eyes.

Alex: I think your wife and my wife would get along really well [laughs].

Have you ever done that?

Geddy: I haven't. But maybe if I'm in an airport at that time of the evening and I see a digital clock...

You allow yourself a little smile?

Geddy: Yes, I do.

It's this level of geekiness in the fans that was so well-portrayed in that famous scene from the film I Love You, Man, when two buddies are at a Rush show, watching you play the song Limelight, and singing every word to each other. It's all rather embarrassing, and we've all done it.

Geddy: Well, that movie definitely hit upon that thing of going to a show and letting go and enjoying the moment. And I think that's an important thing to remember when you love rock music: that there is a sort of freedom in allowing yourself that sense of abandon, and digging your band. From the outside looking in it can be embarrassing, for sure.

With such a loyal fan base, Rush are the biggest cult band in the world. Is that, for you, the perfect scenario?

Geddy: Pretty much, yeah. There's nothing wrong with that.

Alex: For us, having that cult status for so long was a real safety net. You could be sort of famous, really well-known to a small pocket of people, and carry on an existence that was perfectly normal. There is a degree of discomfort that comes with being famous, but it's part of the job. And, hey, there are worse problems.

Geddy: I think for many years people didn't know much about us, and we were never crazy about doing a lot of press. But as time has gone on we've grown more comfortable with ourselves, more comfortable in our role as a band and more comfortable around people, and I think that has contributed to our appeal. When people see this band, how we've stuck together and remained friends for all this time, I think that makes people feel good about the possibility of long-term relationships [laughs].

Alex: And despite the success and the fame that comes with it, I think you can balance it. With fame you can't just shut it off and be a dick. You have to be at least a little bit open and gracious. I think you have to give some time to people that support you, who care about what you're doing and are moved by it. It's a matter of courtesy. I was raised by my parents to be very courteous. It's in me, and I'd feel badly if I brushed somebody off or was rude to somebody.

You've talked about this band being in its final stages. When it's finally all over, will you stay active in music?

Geddy: Most definitely. It's in my nature to be productive. I like to be active. So music will always be something I hope to do in whatever context it is. Also, musicians and artists don't retire. You either work or you stop working. When people talk about retirement it infers punching the clock, and I don't like to look at my life like that.

Alex: The idea of retiring - sitting on a beach in Florida, that sense of retirement - is not what I would do. I would travel. And I would be as active as I could be. I get these offers to play on people's records, do some production, and I would pursue that even more. I love writing. I'm always writing music when I'm home. And I always want to play guitar as long as I can.

Clockwork Angels was such a big success. It was number one in Canada, number two in the US, and was widely acclaimed as one of the best albums Rush have ever made.

Alex: I felt like we'd really accomplished something with Clockwork Angels - a record that did really well at this late stage of our career.

Geddy: I wanted to tour that album forever. I had so much fun on that tour.

Are you already thinking about another album?

Alex: Geddy and I have talked about getting together on our next time off and just writing for the fun of it. Neil loves recording and always has.

Geddy: But to do another record, it has to have that one hundred per cent commitment from all of us. I don't think you can go into a Rush record, or any Rush project, half-assed. You've got to really want to do it.

So...

Geddy: The conversation about future albums has to wait until after this current tour. But there is no negativity about it.

You've said there will be no big tours for Rush in the future. Could you envisage making an album but not touring with it?

Geddy: I can see us making a record and playing live but not playing a lot of shows. I can see us doing a record but not doing a tour.

Alex: I could see us doing two or three weeks of dates. A few years back I saw David Gilmour, the On An Island tour. I think he did eighteen dates on that tour. He was out for a few weeks, and that was it. When I saw that show, oh my God, it was so amazing. He was playing so well. And what a fantastic presentation! And he probably put the same amount of work into doing those three weeks that we would put into doing ten months. And that's kind of cool, that you would commit that amount of energy and work to do just a few dates and that's it. I can see us doing something like that.

Tickets for your current US tour have sold very fast.

Alex: They have. I think maybe a lot of Rush fans are anticipating that this may be the last major tour that we do, and they want to get their last dose in [laughs].

Led Zeppelin were such a huge influence on Rush in your early days. Can you understand why Robert Plant refuses to do a Zeppelin reunion tour? It's a frustrating situation for Jimmy Page.

Geddy: I can see that. I understand how Jimmy Page feels. He still wants to do it, and Robert has moved on. But Robert is no less busy, he's just busy with fresh things, he needs new stimulus. And I have total respect for that.

Do you also feel, as a singer of a certain age, that Plant has the most to lose if Zeppelin re-formed?

Geddy: Yes. It's harder for the singer, in many ways. When the singer ages in front of the public, they can hear it. To be the singer in Led Zeppelin, it's a fucking tough job. It takes a lot of discipline and a lot of work. So I understand his reluctance to want to do that again, whereas he is very creatively fulfilled with all these various projects that he does. Good on him. I'm happy for him.

You've done a lot of rehearsals for this US tour. Do you really need to?

Alex: Oh yeah. I started in January, playing more regularly. Through March I was at my studio four or five days a week for three or four hours of solid playing. Neil and Ged did the same thing a month before rehearsals. We rehearse for the rehearsals!

Why?

Alex: We like to be so prepared for that first show that we feel like it's our twentieth show. It pays off. That first night, you feel confident. That's the way we've always done it.

So what is in the set-list for this tour?

Alex: We've dug deep. We've pulled out some songs that we haven't played in a very long time. We've pulled out some real fan favourites. And we're enjoying playing them. We've revisited every era except maybe the mid-eighties era, which we covered in a good portion of the set on the last tour. We've not included anything from Power Windows or Hold Your Fire, but there's something from just about every other record.

Can you be more specific?

Alex: We're bringing the Hemispheres Prelude and Jacob's Ladder and Cygnus X-1. It's fun and exciting to play these old songs. Jacob's Ladder sounds amazing! For years we've discounted it, although it was always a fans' favourite. We've got three sets - A, B, C - which we'll be rotating throughout the tour.

Geddy: It's funny, some of those old songs sound so strange to me now, but when you start playing them you get back into that head-space you were in when they were written and recorded.

You fall in love with those songs again?

Geddy: It's really all about your sense of perspective. A few years ago we brought back The Camera Eye [from Moving Pictures]. I never wanted to play that song. I never thought it was particularly worthy. And yet it was one the most requested Rush songs. I couldn't understand it. How could people be so wrong?

So what changed?

Geddy: I realised I underestimate the moment in time - the context of that moment. When we started playing The Camera Eye, I thought, okay, there are a lot of pretentious moments in this song. It hasn't aged well. But then I started re-learning the keyboard parts and putting together a slightly different version - instead of eleven minutes it clocks in at nine-and-a-half. And in the playing of it, yes, I fell in love with it again. And that's where it becomes very subjective, and not objective. I stopped being able to tell if it was a pretentious song, and I just enjoyed playing those chords and I remembered why the song got recorded in the first place - I liked the chord progression and the vocal melodies. You can go back to that time and appreciate what you were trying to do. This song - it was a point in your life, and fans want to relive that point in your life and you can have fun playing it. I dig the hell out of that song now.

What else is planned for the tour?

Alex: Ged and I have gone crazy on bringing out all of our old instruments and buying up vintage gear all over the place. His goal is to play a different bass for every song in the show.

And for Rush fans in the UK, the big question is very simple: will you coming back?

Geddy: I'm always coming back. I spend a lot of time in London. I have a place there. It's one of my favourite towns on earth.

You know what I mean - your fans in the UK want to see the band play live again.

Geddy: There's nothing on the cards right now. I would say that there are those of us that would prefer to do some dates in the UK and even some European dates, and there's an opportunity, once we get rolling, to see what we might want to add. But let's just say that at this point that Neil's made it clear that he's good with this US tour being the last group of dates.

Alex: You never know. These past couple of months have been pivotal. It's shown us, after a year and a half off, how much we really love doing what we're doing. I think that's really important in Neil's case. But when you've only got so much time to play with it's tough.

So you're letting us down gently?

Alex: Well, like I said, you never know what will happen. But I'll say one thing: Geddy feels it's important that we go back at this time to the UK, to acknowledge the support you've given us for all these years. And I agree with him.

KISS & US!

In the 70s, Rush embarked on an eye-opening tour with the gods of thunder

In 1975, Rush hit the road in the US for their first major US tour, as the opening act for Kiss. There was a marked contrast between the two bands: Kiss with their larger-than-life cartoon superhero image and 'rock-and-roll-all-nite' party-rock anthems; Rush with their intellectual prog-metal and serious muso chops. Also, Kiss were bullish New Yorkers, while the guys in Rush were relatively genteel Canadians.

"We were close with those guys on that tour," says Alex Lifeson. "It was their first tour, our first tour."

Yet there was a cultural divide between them that became evident as the tour went on.

"We were so green," recalls Geddy Lee. "Really, you can't imagine how green we were. Being on this rock'n'roll tour, it was like our own personal circus. Watching the guys from Kiss, it was all so funny to us."

Both Lee and Lifeson have fond memories the times spent hanging out with Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley. "Ace has the best laugh on planet earth," Lee says. "So we spent most of our time trying to entertain him. We'd all go to Ace's room and get high and get silly and it was fun. Ace wasn't bothered about anything other than having a good time and drinking too much. He was the most personable of all those guys."

But there was less of a connection between Rush and the two leading figures in Kiss - Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons. And it was the latter's obsession with sex - specifically, banging as many groupies as possible - which Lee and Lifeson found difficult to relate to.

Lifeson also says that in the years that followed, the camaraderie of that first tour together was lost. "With Paul and Gene there was always a distance," he says, "and that distance grew very quickly as they became more popular. There were times when we tried to reconnect with them, and they really weren't interested and had moved on. But that was a very long time ago."

Thin Lizzy & Us!

Rush on touring with Phil Lynott and co.

Out of all the bands that Rush gigged with in the 70s, they had the most fun with Thin Lizzy and UFO. At least that's how they remember it. As Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee admit, it's hard to remember everything that happened out on the road, when most nights ended in a big piss-up.

Lifeson describes UFO as the hardest-drinking band he has ever known. "Their drinking was a lot more chronic than anything we were doing," he says. "We would never drink before a show, and they were already plastered by soundcheck. That's just the way they operated."

When Rush first toured with Thin Lizzy, in 1976, both bands were just breaking big: Rush with the 2112 album, Lizzy with Jailbreak. They bonded over a whisky-drinking contest instigated by Lizzy's Scottish guitarist Brian Robertson - a challenge that 'Robbo' lost, along with the contents of his stomach.

"Brian was such a nut," Lifeson says. "But we connected on a deep level. It wasn't just about drinking and partying and being crazy. There were a lot of discussions about literature and lyrics and music. Brian had the biggest heart. We loved to play and we loved to laugh. We were like brothers, Brian and I."

As for Thin Lizzy's leader, Phil Lynott, it was a rather different story. Geddy Lee remembers Lynott as "an isolated, solitary dude". Lifeson adds: "Phil was a very sensitive soul, very bright, but there was a mysterious side to him." It was in 1986, 10 years after Thin Lizzy and Rush toured together, that Lynott died from multiple organ failure caused by heroin addiction.

"It was sad to see Phil go," Lee says. "To be honest, I had no idea that he was into what he was into. Maybe I'm naïve. I've had people that worked for me that had bad problems over the years, and I always felt like I was the last guy to know. But I find that with so many of those tragic figures. There's not enough people that are aware of how bad off they really are. Otherwise there would be an intervention. And those people that are into drugs so heavily are very good at fooling everyone."