Magnetic Memories: Four Decades in the Studio with Rush

40 Years In The Studio With Rush In this self-penned memoir, Neil Peart reminisces about the sessions he played, and all the things he learned along the way

By Neil Peart, DRUM!, December 2015, transcribed by John Patuto

My first experience in a recording studio was around the age of seventeen, when I had been playing for four or five years. Those seem the most important details - age and experience. For the record (ha!), it was early 1970, and the band was J.R. Flood, from my hometown of St. Catharines, Ontario. We were thrilled to be invited by a record company - actually two companies, in that one year - to make a demo of our original material, in professional-grade recording studios in the "big city," Toronto.

We figured we had pretty much made it.

J.R. Flood was a serious band, my first "full-time pro" outfit, with Paul Dickinson on guitar, Wally Tomczuk on bass, Bob Morrison on Hammond, and Gary Luciani singing. They were a good bunch of guys, disciplined and dedicated - and funny. (I've been lucky that way.) We practiced hard every weekday in the Dickinson family basement. (Paul's mother has surely been sainted.) Weekends we played at high schools and small halls around Southern Ontario. What had been called "dances" in the early '60s were firmly "concerts" by 1970, when pretty well everyone in the audience sat down on the gym floor or stood around the walls to listen and watch. That was a nice level of attention for a young musician to feel.

Best of all, in those times there were gigs - audiences - available for a night or two every weekend. Plus the musical climate was open enough that our originals were welcomed along with the cover material. (The drinking age in Ontario was still 21, soon to be lowered to 18, which would change everything for local bands - not necessarily for the better, I'm afraid. With alcohol involved, fewer people tended to "listen and watch.")

J.R. Flood played covers of bands we liked (a few by Santana and Blood, Sweat & Tears, Jethro Tull's "Teacher," Deep Purple's "April," that I recall offhand), and had a small repertoire of original songs (among them my first two attempts at lyrics, "Gypsy" and "Retribution").

However, if the local live-music scene was healthy in the late '60s, the music business was not so robust, at least in the Great White North. The paths to success were an alternate-universe version of what young musicians everywhere face today - the conditions were unfavorable, and the odds were slim. Canadian record companies were mere satellites of American labels, or tiny, local independents. They had little power in either case, and were certainly not interested in a band with no obvious singles - the gold standard of the day. (Again, not so different now; it's still all about one song at a time - only the media have changed, not the mechanics.) So, they "politely declined." Still, it is gratifying that we were at least given a shot.

It was a big deal to us, all right, and an unforgettable experience to be in a recording studio for the first time. For one thing (it only occurs to me now), we had never heard ourselves play! Impossible to imagine today, but there were no inexpensive portable recording devices in those days, let alone video cameras (so far as we know, only a single, silent Super 8 clip of J.R. Flood, shot by my father, survives), and I'm pretty sure it's true that we had never actually heard a playback of ourselves in any form.

However, perhaps the reward for that lack was that we had learned to hear each other, listen to each other, deeply, in real time. Musically, the five of us interacted very much as an organic union greater than our individual parts. That was an education acquired in one irreplaceable way - in live performance - and I would still maintain there is no better school. At least, I would stress, if you are working with like-minded musicians as good as or a little better than you, as I was lucky enough to do in J.R. Flood.

All of our songs were long, averaging five or six minutes, with a couple around ten minutes. One of those epics was charmingly titled, "You Don't Have To Be A Polar Bear (To Live In Canada)." The arrangements were intricate, and included long instrumental passages with solos, punctuated by tight ensemble sections, and occasional verses and choruses.

That approach would work pretty well for Rush a decade or so later, but ... not yet.

In recent years I have been able to locate, revive, and review those old J.R. Flood mono tapes, and they tell many stories.

As mentioned, we were very disciplined and well rehearsed, and we nailed decent versions of our songs in one or two takes. The engineer that day was a bit of a comedian, as can be heard over the talkback between songs. If a technical problem ended a take, he would come on the mike and say something like, "'Giant Killer' take 11," when it was the second take. Hilarious stuff like that.

Similarly, right from the beginning he seems to have taken a superior attitude with these rubes from the boonies in a studio for the first time. At one point I hear my voice between takes trying to explain that I can't hear anybody else in my headphones - of course I don't know what needs to be done about it, and he doesn't help. He just makes some snickery remark like, "Maybe you shouldn't play so loud!"

So I guess this is where we get to the "advice" department, for those without recording experience. The more things change, the more they stay the same. I doubt if a single musician in these times has not been hearing him - or herself recorded since ... before they were born, right? So I'll try to be more "conceptual" than specific.

For example, don't presume that anybody is going to help you - either an unsympathetic engineer, or in a home-studio situation, because nobody in the room knows any better than you do how to record drums.

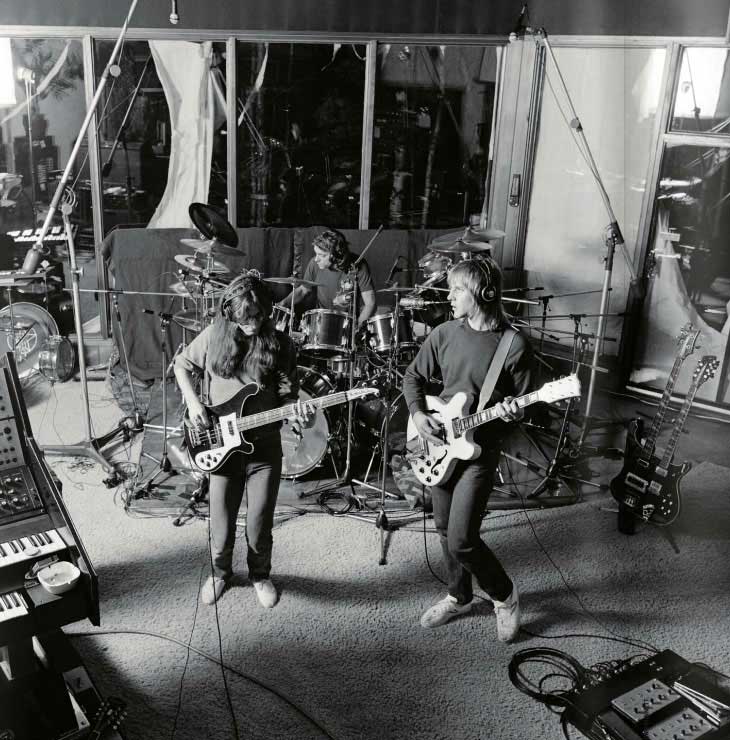

Another "teachable aspect" of my first experience is that J.R. Flood simply set up our gear in a big room, pretty much in our usual stage-and-rehearsal order. We were separated just enough to keep the instruments and amplifiers isolated, but we could see each other. (We often relied on visual cues for solo endings and such, just as Alex, Geddy, and I sometimes did onstage.) The engineer put up a complement of microphones in standard configurations, tested them, and we started playing. Even vocals were recorded live, in an isolation booth, and because it was a demo, there was no consideration given to overdubs, double tracking, repairs, or even mixing.

It was what it was. Not bad for its time.

I listen to myself at that age, all energy and variable control, and think, "Somebody give that kid a valium."

Or, of course, a click-track.

Here's how I described the experience in my book Traveling Music (ECW 2003).

J.R. Flood had a fairly slick and ambitious manager, Brian O'Mara, who managed to arrange "demo sessions" for us with a couple of Canadian record companies in 1970. It was certainly exciting to be in a real recording studio (first at Toronto Sound Studios - coincidentally, where I would later work with Rush on our first three albums together - the other at RCA, later called McClear Place, where so many of our later albums would be recorded and mixed), but nothing came of that - the record companies "didn't hear a single."

Recently I dug out those ancient reel-to-reel mono tapes and had them "resurrected" by an archival specialist. How funny to hear myself at 18, with more ideas than skill, more energy than control, and more influences than originality - a raw blend of Keith Moon, Mitch Mitchell, Michael Giles, and Toronto drummers Dave Cairns from Leigh Ashford and Danny Taylor from Nucleus.

Striking Out

Following the disappointment of that rejection, there didn't seem to be any future for us in that small pond. There's a line in the Rush song "Caravan" that sums up my attitude then: "In a world where I feel so small, I can't stop thinking big."

I urged my bandmates to be bold. "Let's move to Toronto, or New York - hell, even London! Come on - we could do it!" But no one shared my restless ambition. So, I had to "think big" on my own, and in the summer of 1971, my dad and I crated up my drums and records, and I moved to London, England. I considered London to be the "rock capital" at that time, so it seemed like the place to be - to seek my fame and fortune, of course. Those dreams weren't immediately realized - and not in London, but back home in Canada - but the experience was a pivotal character-building era in my life. My first time traveling alone, of traveling anywhere more than a few hundred miles from my childhood home, and first time living on my own and supporting myself. Or not. I became acquainted with poverty and disillusion, did the rounds of "blind auditions" (see Traveling Music for more tales), but was able to play with a few bands, have a few more recording-studio experiences, and learn a great deal - about music, life, and myself.

I had the opportunity to do a couple of sessions as a "hired gun," for example, and found the experience wasn't for me. I wanted to be in a band that recorded songs to play live (the underlying trajectory of Rush, I would say). Such decisions are always going to be individual - for some the point of honor is to make a living playing music, period, and I understand and respect that. However, when I tried playing music I didn't care for, just for the money, I found that wasn't for me, either. I felt I would rather make my living some other way, and keep playing the music I liked.

Back home in Southern Ontario in early '73, I went to work at Dad's farm equipment dealership, and played part-time in bands. By the summer of '74, I had put together my own band with guitarist Brian Collins, and we rehearsed weeknights after work. We started playing local bars (making for late nights and early mornings for me) under a name Brian brought from his previous band, Hush. One day that July, as I stood behind the parts counter, a man drove up in a white Corvette - co-manager of a band from Toronto called Rush.

The rest is hysteria.

Recording Rush

We began touring in August 1974, and went into the studio that winter to record our first album together, Fly By Night. With co-producer Terry Brown, we had ten days to write the songs (bringing a few embryonic ideas worked out on the road), and record and mix them. So that was crazy.

Six months later we came off the road to make another record, Caress Of Steel (I think we had three weeks that time) and six months after that we came off the road again to record what would become our breakthrough record, 2112, in the winter of 1976. By then we had a whole month to write, record, and mix - but it was still crazy.

A live album, All The World's A Stage, gave us a breather before our next studio album, A Farewell To Kings, in 1977. Flush with a little success now, we traveled to Rockfield Studios in Wales for the recording, and Advision in London for the mixing, and that was exciting. (In subsequent years we worked in studios around England and different parts of London, as well as even more exotic locales like Air Studios on the Caribbean island of Montserrat, and Guillaume Tell in Paris, France.) Starting with A Farewell To Kings, each of us branched out into new areas of instrumentation, including keyboards, bass pedals, and, for me, every kind of percussion instrument front temple blocks to orchestra bells. We also experimented widely with different approaches to songwriting and arranging, as well as recording techniques - even recording outdoors, or inside echo chambers.

Then it was back on the road, headlining now, so playing longer shows, and to audiences with "greater expectations." In the summer of 1978 we returned to Rockfield, weary from touring, and with only a few days to work on new songs - and an ambitious piece of work before us, Hemispheres. Looking back, we all acknowledge that it was the record that "nearly killed us." Overwork had finally caught up with us all, and now combined with over ambition. By the time we "abandoned" that album (I always liked the saying, "No work of art is ever finished, it is only abandoned"), we were left mentally and physically spent. Again, crazy.

Our next album, Permanent Waves, was recorded back home in Canada, at Le Studio in Quebec, in the fall of 1979. Before driving there for the first of many unforgettable visits over the next 14 years or so, we spent a few weeks at a country place in Ontario, just to work on the songwriting. That became our pattern for a long time. It was much less crazy, and much more fun.

Studio Secrets

Whatever casual recording goes on during the arrangement and demo stages, I know I can always rise to a higher level when we're recording for real. It is the same on the day of a concert, I wake up mentally focused on that goal, determined to play the best I can, every time.

Some lessons learned slowly can be recounted quickly. Sound-wise, I grew to prefer my drums to have both batter and resonant heads, at first with small open-ended concert toms, then later putting bottoms on those as well.

I like a little damping on the bass drum's batter head, but none on the other drums. Engineers used to balk at that, but as I gradually learned to tune the drums well, so they didn't produce any unwelcome overtones, that "openness" became acceptable to the audio professionals, both in the studio and live. Same with having a front head on the bass drum - more difficult to record, but much nicer to play, with bounce from the batter head, and real dynamics.

These elements helped to make my own sound more "characterful," and many drummers agree that their "signature" easily trumps any consideration of particular drums or even heads. I have played on thrown-together rental kits and still come out sounding entirely "like me" - for better or worse.

Being somewhat of a purist, I also resisted editing at first. I wanted to deliver a performance in a single take that was "everything it ought to be." That principle became a big influence on my approach to recording - I would compose and rehearse my parts for hours and days, to the point where I could do that.

Then, gradually reversing direction, I began to embrace editing. One early lesson was in 1978, recording our Hemispheres album. The last song was a crazy eight-minute instrumental, "La Villa Strangiato," and we played it over and over - for about four days, I recall. The three of us were in the studio together grinding it out, over and over, sometimes until daylight, only to start again later that day, with aching, swollen hands. It was soul-destroying. Finally, Terry Brown tried editing together three takes into one, it sounded great, and I had to cry, "Uncle."

From then on I continued to try to avoid the need for editing - with careful preparation and recording-day determination - but did not resist it if it seemed necessary, desirable, or just time-efficient.

These days editing is no longer a surgical operation with razorblade and tape, but a matter of simple digital punch-ins. Thus it has become a valuable tool to me - especially as I pursue greater improvisation in my recorded drum parts. Typically I will try to get a good solid take, then keep going - attempting more random, "dangerous" experiments that sometimes produce a fill or a passage that is unique and exciting, then add it to the "solid" take.

That final master drum part can be learned and reproduced later - as I did for the tracks on our most recent Clockwork Angels album, for example, when it came time to play them live. For me, a performance like that combines the best of composed and improvised parts.

To Click

I first used a click-track in the studio on our Permanent Waves album, in 1979. Right away, the click became my "friend," a guide that kept me nailed to the tempo, and gave me more freedom, in a way - one less thing to think about. Over time I learned to work with the click - pushing and pulling against it deliberately, to make certain passages more urgent, or more relaxed.

I used the usual eponymous "click" sound for many years, then switched to a tambourine sample - softer and somehow "looser."

In 1985, preparing for the Power Windows album, we rehearsed the songs together, but recording technology at that time was becoming both sophisticated and "artful." Co-producer Peter Collins and engineer Jimbo Barton urged us to try recording our parts separately. (We have always liked to have a co-producer, to give us an objective ear and as an "arbitrator," but still carefully protect our own role in that department by calling it "co" producer.) The reasoning was not only for greater control sonically, but also for greater focus on each performance, so it seemed worth trying.

The drums came first (as they should!), and I went out alone and played to a "guide track" of guitar, bass, and vocals. It really wasn't any different as a "musical experience" - I was still playing to Alex and Geddy, and to the song. The guys stayed in the control room, as part of the production team and "panel of judges." Under such microscopic scrutiny, pleasing everyone could be challenging, and even trying to a weary drummer's patience. However, I could not deny that the drum parts were elevated by that process - they continued to get better, not just different. (A crucial distinction.) For my own "part," so to speak, I felt better being able to work at a song for as long as I felt it needed, without feeling I was making anybody else work too hard.

By that time we had been playing together for more than ten years, so whether or not it was in "real time," we always played to each other. One big improvement in this method was that when Geddy rerecorded his bass part to my master drum track, he could play to every detail and nuance, making our rhythm-section performance tighter and more sympathetic than real-time could ever allow. (I often ask for a copy of that bass-and-drum basic track - just because.)

On the 2007 sessions for Snakes And Arrows, with Nick "Booujzhe" Raskulinecz, he urged us to try a few songs with all of us in the room together. We obliged, and he was soon convinced that it didn't change anything, and returned to our method.

For the recording of Clockwork Angels, in 2011, again with Nick, I pushed that method in a new direction. Determined to capture performances that were more spontaneous, I deliberately avoided preparing. In the studio, I would play along with a song a few times, get a feel for the sort of patterns and "decorations" that might work, then call Nick into the room and we started recording. I didn't even wait to learn the arrangement - just followed the baton wielded by Nick in front of me, conducting me into the changes, directing me toward different areas of the kit for the next section. Between takes, we would consult on what seemed to work, and what other ideas might work.

That was different, all right - but once the basic arrangement was worked out, and magic (or lucky) moments were "comped" into the master, I was delighted with the results. As I wrote in a story about preparing for that Clockwork Angels tour, I was pleased to note that, "The way I play now is the way I always wanted to play."

That is a fitting reward for almost 50 years of effort!

Or Not To Click

Back in 1979, along with introducing the click track, we also started using digital sequencers (like in the chorus of "The Spirit Of Radio") both in the studio and live, and on subsequent albums they would figure ever more. At first I would just have those sequences up loud in my floor monitor (the root of my hearing damage, I am convinced), then I tried headphones - especially for the sixteenth-note sequence in "Vital Signs," from Moving Pictures.

The eventual development of in-ear monitors solved the audibility problem, and that part of the job became much easier. Until the Clockwork Angels tour I had never used a click track live, except once years ago to stay in sync with a rear-screen film. For this tour it was helpful because we had eight string players in the Clockwork Angels String Ensemble, and they sometimes needed it when I wasn't playing. Even in certain passages when I was playing, it helped us all to stay together.

I was also required to stay in tempo with some long, legato sequences of keyboard or vocal effects, and the tambo-click helped with that, too. Even so, I am glad to say that the click appears in only a tiny percentage of the show, and only when absolutely necessary - or at least, "absolutely helpful."

On most songs, I prefer to hold it together myself, and let the band be a living, breathing organism that can push and pull naturally. These days many bands perform to a preprogrammed basic track, often a computerized software program. We always resisted that rigidity.

Speaking of rigidity, one cautionary note - after some years of working with clicks and sequencers to that degree of exactitude, I felt my playing was getting stiff. If that was the price of precision, I didn't like it - but what to do? In the mid-'90s I studied with the late Freddie Gruber, who emphasized movement over technique - or at least movement in the service of technique - and he helped greatly in loosening me up. A little over ten years later, in the late 2000s, I studied with Peter Erskine, and he also guided me along the road to more relaxed tempo control and improvisational ability. I owe much to them, and to my first teacher, Don George - all of them contributing to my development along the way.

Parting Thoughts

Finally, I can only conclude with encouragement. As I acknowledged earlier, times are tough for musicians starting out - but they clearly were for me in Southern Ontario in the 1970s, too. Miracles do happen.

Maybe you will be one.

In any case, whether or not your music supports you, it can still nurture you. It is not given to every aspiring musician to make a living at it, never mind fame and fortune, but it can still be a rewarding lifetime pursuit. I know several "nonprofessional" drummers who find joy in playing the instrument, sometimes with friends, and gradually getting better at it. (Because you do. When people ask me about my favorite recorded performance, I am taken aback - if I didn't think my most recent work was an improvement over the past, I hope I would give up.)

Other than "practice, practice, practice," the only unqualified advice I can give to beginning drummers is to play live, in front of people, as often as you can. Nothing teaches you more about where the nexus lies between what makes you excited, as a player, and what excites an audience. If the ideal is to play music you like, and have other people like it too, then the definition of luck fits perfectly: where preparation meets opportunity.

You really cannot play too much, on your own, with a band, and onstage. As Picasso said, "Inspiration exists, but it has to find us working."

The more you are practicing your chosen art, the more likely you are to stumble upon inspiration in that work. (It's probably safe to say that more inspiration is stumbled upon than delivered from on high.)

Years ago I read about a tabla player who practiced every day, but he said that only about every ten days did he feel he "got somewhere." Beginning a long period of daily practice under Freddie Gruber's teaching in the mid-'90s, I took that to heart, and found it to be true. The important thing is to keep striking that flint and steel, and eventually you will produce a spark.

One related bit of wisdom I have acquired, in music and in life:

"Magic happens - but it often requires some planning."

Determination, too.

Excerpted from Pete Vassilopoulas' forthcoming book Recording Drummers.