Neil Peart Reflects On 50 Years Of Hitting Things With Sticks

By Neil Peart, Drumhead, December 2015, transcribed by John Patuto

Not being one for celebrating personal "occasions," I am always content to mark milestones like birthdays quietly, privately. Not that I deny them - each September I am proud and grateful to have survived another year, and lately, at age sixty-three, to be in my seventh decade. I just don't like to make a big deal about it, or have others make a fuss.

For that reason, it was a few days later when I realized where I had spent my fiftieth anniversary of playing the drums - at a concert at the Hollywood Bowl. Having played there a few times with Rush over the years, it was fitting in that way - but this time I was with my wife Carrie and six-year-old daughter Olivia to see the Psychedelic Furs and B-52s.

I loved the Furs in the '80s, and Richard Butler's solo album in the 'noughties was a favorite for about two years. They and their songs still sound really great. The B-52s are nothing if not fun, of course, and all through her childhood Olivia had been dancing wildly to "Love Shack." To watch her dancing (wildly) in the aisle at the Hollywood Bowl with her mother was as they say, "priceless."

Lately Olivia has been introducing me to new friends at school as "my dad - he's a retired drummer." True to say - funny to hear. At the Bowl, two fine drummers appealed to dad's professional (retired) appreciation: Paul Garisto nailing the perfect balance of aggressive and artful rhythmic drive for the Furs, and Sterling Campbell laying down a powerful, solid groove for the B-52s - wonderfully abetted by Tracy Wormworth's muscular and immaculate bass playing.

Then there was the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and the fireworks finale to crown an unforgettable family evening. The occasion felt "well celebrated."

That night of September 12, 2015, was also my sixty-third birthday, which was no coincidence. Because it was for my thirteenth that my parents gave me drum lessons. No drums, you understand, just a pair of sticks and a practice pad. Every Saturday morning I would catch the bus to downtown St. Catharines (Ontario) for a lesson with Don George at the Peninsula Conservatory of Music on St. Paul Street.

Even there I wasn't playing drums, because other instruments were being taught in neighboring rooms. As arrangement of metal-rimmed pads mimicked the layout of a four-piece set, with a bass-drum pedal, hi-hat and a ride cymbal with a "sock" around it. I learned my rudiments, elemental sight-reading and basic drum-set patterns in a combination of thuds and clicks. I can still hear that sound. (One time Don asked me to improvise around the set a little, and after I did he nodded and said, "Nice. Some of that might not have sounded great on real drums, but the spirit was good.")

Don gave me my first and most important encouragement, mentioning my friend Kit Jarvis, too. "Of all my students, you and Kit are the only ones who can be drummers if you want to." That meant a lot.

As for not playing real drums that first year, fortunately I always had a good imagination! I would array magazines across my bed in a layout of Gene Krupa's drums, or later Keith Moon's, and beat the covers off them. I sat on a stool in front of a mirror and waved my sticks around - like a maniac I dreamed of becoming.

Mom and dad said if I stuck to the lessons and practiced for a year, they would think about buying me drums. Sure enough, the next year they got me a three-piece set of Stewarts ($150) in red sparkle, bass drum, snare drum, one tom and one small (clanky) cymbal.

That first day my shiny red jewels were set up in the living room, and over and over I proudly played my two songs, "Wipeout" and "Land of a Thousand Dances" (a local band played a cover of that with a cool drum part). Then I moved them piece by piece upstairs to my room, and every afternoon after school played along with the pink spackle AM radio on the steam radiator besides me. Whatever song came on the Top 40 station, I tried to play along.

Next, mom and dad got me a hi-hat, then a floor tom, and I saved up paper-route and lawn-mowing money for a pair of Ajax cymbals. And I still played along with the radio to the hits of 1965 and '66. (Perfect time to quote a contemporary drummer who remarked of that time, "My six favorite drummers were all Hal Blaine!")

So that's where I started, fifty years ago, and what a run it has been.

Forty-one years with one band - three young guys who grew up together in music and in life, going through everything music and life can throw at you. All the while, we were doing what we wanted, the way we wanted to do it.

That's the quality I'm most proud of, really - just that we can stand as an example, in the face of what often seems like a factory of corporate entertainment. If nothing else, we showed that it is possible to make a career of music without giving away - or selling - your soul. You just have to be determined. And of course, lucky.

I can't quite give the "wouldn't change a thing" statement you sometimes hear, as there are elements in both music and life that I wish had gone better. A line in our song "Headlong Flight" was inspired by my late drum teacher, Freddie Gruber, "I wish that I could live it all again." Toward the end of Freddie's long and eventful life, he meant it literally, wanting every experience and sensation again, just as it was. Some people rightly see another interpretation in the way I used the line - a wish that one could do it all again better. But never mind, regrets are ultimately ... not helpful.

The third teacher in my Holy Trinity, Peter Erskine, modeled a way of looking back on your younger self with a buddha-like ... amused tolerance. He talked about the unthinking way he used to set up his drums, or how limited his playing has been in some technique, with a knowing, comfortable smile. If he was foolish and lame then, he was better now, and that's what mattered.

It was Peter who helped me conquer - or at least attack - what was for me the Final Frontier: improvisation. Having developed a certain amount of compositional tools and habits over forty years of playing, I was determined to become freer and more spontaneous. Peter helped me toward that goal with guidance in developing deeper time-sense and greater musicality. (With credit to Nick "Booujzhe" Raskulinecz, too, who encouraged and enabled my improvising in the studio.)

Now after fifty years of devotion to hitting things with sticks, I feel proud, grateful and satisfied. The reality is that my style of drumming is largely an athletic undertaking, and it does not pain me to realize that, like all athletes, there comes a time to ... take yourself out of the game. I would much rather set it aside than face the predicament described in our song "Losing It." (From 1982 it was performed live for the first time on our fortieth anniversary tour, R40, in 2015). In the song's two verses, an aging dancer and a writer face their diminishing, twilight talents with pain and despair, ("Sadder still to watch it die, that never to have known it.")

You have to know when you're at the top of your particular mountain, I guess. Maybe not the summit, but as high as you can go. I think of a Buddy Rich quote I used in a book, Roadshow, about our R30 tour, ten long years ago: "Late in his life, Buddy Rich was asked if he considered himself the world's greatest drummer, and he gave an inspiring reply: 'Let's put it this way: I have that ambition. You don't really attain greatness. You attain a certain amount of goodness, and if you're really serious about your goodness, you'll keep trying to be great. I have never reached a point in my career where I was totally satisfied with anything I've ever done, but I keep trying.'"

I recently picked up another great quote, this one from Artie Shaw. As many readers will know, he was a celebrated big-band leader and clarinetist (he called Benny Goodman "the competition") who famously gave up playing at age forty-four. This summation of his career really resonates with me now. "Had to be better, better, better. It always could be better...When I quit, it was because I couldn't do any better."

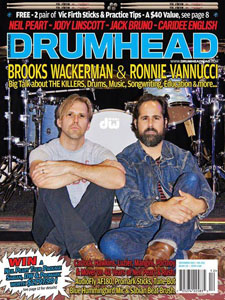

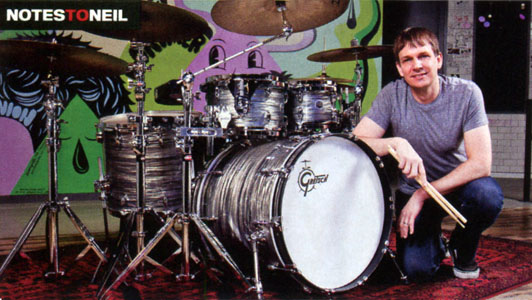

Notes to Neil

Neil and Rush changed my life. I became a huge fan while in grade school. At that time, I got so hooked that I really couldn't listen to much else! They were the "IT" band to me for many years and I credit Neil for giving me so much musical insight that helped me develop my craft and ears.

Neil and Rush changed my life. I became a huge fan while in grade school. At that time, I got so hooked that I really couldn't listen to much else! They were the "IT" band to me for many years and I credit Neil for giving me so much musical insight that helped me develop my craft and ears.

Neil's drum parts are always an amazing composition within themselves. They are a huge part of the song and arrangement. That's why you see all the air drummers at the shows! The way he would structure his parts always made a huge impact on me. And the odd time signatures. I learned my first odd-time grooves playing along to Rush records.

I have had the pleasure of working with Neil's drum tech, Lorne "Gump" Wheaton on a few Steely Dan tours when Neil didn't need him. Through that connection, I was fortunate to meet Neil as he came to a Steely Dan show in L.A. back in 2003. He couldn't have been more gracious to me and it was an honor that I will always remember.

Neil, congratulations to you and to one of my all time favorite bands on the planet for 40 years of incredible music! - Keith Carlock

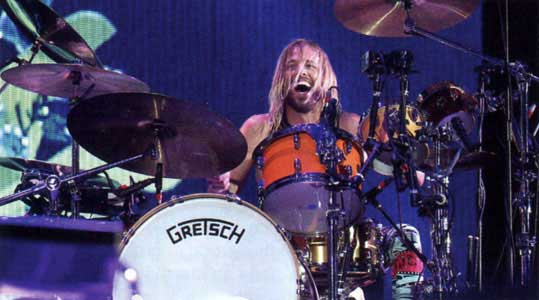

Neil means so much, it's hard to quantify it. He's probably sick of me talking about how important he is to me. A lot of the difficult, tricky, prog-influenced things come from him. Neil Peart taught me how to sound better than I was. I love him. God bless him. His hands are like no others. Nobody can go from a 6-inch tom all the way down to a 20-inch Gong Bass and have the consistency and flow that he has...nobody!

Neil means so much, it's hard to quantify it. He's probably sick of me talking about how important he is to me. A lot of the difficult, tricky, prog-influenced things come from him. Neil Peart taught me how to sound better than I was. I love him. God bless him. His hands are like no others. Nobody can go from a 6-inch tom all the way down to a 20-inch Gong Bass and have the consistency and flow that he has...nobody!

There is a fill on Exit...Stage Left going into the last verse of "Xanadu," (9:50) it happens so fast! His playing is like water at times. There are no rough edges unless he wants them in order to make a statement. It's the way that he plays things like that, with no tension, and at the same time has the musical intelligence to understand where to place it...that's such a high level of mastering any instrument. The first time I saw Neil play was at the Pacific Amphitheater in Orange County. I was in junior high and had only been playing a little while, and that was probably the single most drum-educating moment of my life. I wasn't that close to the stage at the show but seeing him live and hearing the band...it cemented the idea that this was what I wanted to do with my life. I wanted to play music that was complex, but also had a pop sense to it. Neil and Rush can do that. They can make a hook out of a very complex figure, and that is one of the hardest things to do. I don't think you can make that happen, it's just within you or it isn't. Obviously it is part of Neil Peart. He understands what about pop music is good. Listen to "Spirit of Radio," that's a great pop song and his playing is ridiculous on it. I know a lot of people won't even touch that song because of how hard it is to play correctly. Neil is a normal guy except that he has this incredible talent. Whenever we've hung out, I don't bring up drums. I let him bring it up if he wants to talk drums... and then I listen.

I owe him so much. When Dave and I inducted Rush into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, it was an honor to be a part of giving something back. First of all, we don't think that we're anywhere close to that caliber of musicianship, and secondly, there are a million guys that could have done a more accurate Neil Peart impression than I did. I'm sure that there were some people watching and saying, "Really Taylor?" But I love him and I was so happy to be there and show him respect. He is edgy and rock 'n' roll and I tried to honor that spirit. - Taylor Hawkins

Growing up on 118 acres outside of Pittsburgh, you're kind of sheltered on what music you're exposed to, besides the radio and what bands your friends tell you they like. When I was very young, my uncle made me mix tapes of Kiss, Ozzy, AC/DC, Zeppelin, Rush, etc. I would try to play drums to all these songs and specifically remember going from "Back In Black" to "Limelight," wondering why it was so much harder to play, and figuring it out! I went out and bought Moving Pictures right away and became hooked on Pearl's incredible playing ever since. His drumming is always so clean, creative, very powerful and well executed. Then I found out he also wrote the lyrics... What??!! What a rare and incredibly gifted talent to have alongside his insanely great drumming!

Growing up on 118 acres outside of Pittsburgh, you're kind of sheltered on what music you're exposed to, besides the radio and what bands your friends tell you they like. When I was very young, my uncle made me mix tapes of Kiss, Ozzy, AC/DC, Zeppelin, Rush, etc. I would try to play drums to all these songs and specifically remember going from "Back In Black" to "Limelight," wondering why it was so much harder to play, and figuring it out! I went out and bought Moving Pictures right away and became hooked on Pearl's incredible playing ever since. His drumming is always so clean, creative, very powerful and well executed. Then I found out he also wrote the lyrics... What??!! What a rare and incredibly gifted talent to have alongside his insanely great drumming!

Through the decades, his playing continued to inspire me. I've always looked forward to a new Rush CD and saw them live whenever I could. Recently, I took my fiance to see them for her first time. She couldn't believe how may people were air drumming to Neil throughout the whole three-hour set! The last two Rush albums are two of my faves, and ironically, we're now in the studio with Nick Raskulinecz, who produced Snakes & Arrows and Clockwork Angels. He's also produced Deftones, Alice In Chains and Foo Fighters. Of course, I was asking Nick a ton of Rush questions and what it was like to work with Neil. I'm still a huge fan of finding out the writing process of my favorite bands; how they added this, took away that. I love knowing why certain tunes get cut from records, how they're tracked, etc.

While I'm geeking out on one of my Top 10 drummers ever, I also love his line of Sabian Paragons. I use his 19" China and 20" crashes live, and on the new Korn record, I just used his 22" crash & 10" splash. They sound awesome and fit our band's sound well.

I'd just like to say a HUGE congrats on Neil's 40th anniversary of touring and 50th of playing drums! Thanks for the many years of inspiration, not only for your musicality and for what you've done for the drumming community, but also for the longevity of your career and commitment to your band. When I started playing, I knew at a very young age that I'd be a "lifer" in the music biz no matter what; rich, poor, famous, unknown. I didn't care. It's a huge oath and commitment to take and you have to sacrifice a lot. So, seeing Neil go this long and to stay this successful all of these decades; it's beyond inspiring!

Cheers to you Neil Peart, your playing will continue to inspire and will live forever through your CDs & DVDs! - Ray Luzier

Neil Peart made a dent in the drum community like whatever made the meteor crater in Arizona.

Neil Peart made a dent in the drum community like whatever made the meteor crater in Arizona.

The fact that he is doing a 40th Rush tour is a testament to the kind of dedication and intense physical and mental commitment to his craft and his life that he has. This is especially true when his every note is excitingly anticipated, fully absorbed and scrutinized on a nightly basis.

I hope he sets up the Caress Of Steel kit in a room in a year or two, then one night has a sip of wine, and goes for "Didacts And Narpets" smiling from ear to ear with nobody else there, and loves every minute of it. I owe a "thank you" to him for doing something good with the gifts he was given and giving me many fun drum moments after school trying to mimic his challenging and sensible drum parts.

Neil's impression on my drumming is like the Barringer crater. - Mike Mangini

It's hard to sum up the impact that Neil had on me as a young drummer in the early '80s. Before I heard Neil, my drum heroes were Keith Moon, John Bonham and Peter Criss, but once I heard Rush and Neil, my mind opened up to a whole new world of progressive music and I became completely obsessed!

It's hard to sum up the impact that Neil had on me as a young drummer in the early '80s. Before I heard Neil, my drum heroes were Keith Moon, John Bonham and Peter Criss, but once I heard Rush and Neil, my mind opened up to a whole new world of progressive music and I became completely obsessed!

His drumming was my introduction to odd-time signatures and I cut my teeth on learning how to feel and understand odd-time grooves with songs like "La Villa Strangiato," "Jacob's Ladder" and "Natural Science."

He also was my gateway into the world of gigantic drum kits. I would sit and stare at photos of his massive kits in all of the drum magazines the way most normal teenagers would be looking at I Playboy centerfolds! (In 2005, Tama would make me a replica of his classic early 80's kit for my own tribute to Neil & Rush)

All these years later, I am honored to have gotten to know Neil pretty well; he is one of the most generous and humble people in the business, always extending himself to me and my family whenever Rush comes through town.

Neil is also an incredible writer and his books show his tremendous ability to live and appreciate life, which is just as inspiring as his drumming. - Mike Portnoy

I didn't really take to drums until my thirteenth year, but once I did, I quickly made up for lost time by practicing and playing for hours and hours each day. Practicing, for me, was mostly playing with headphones on to all of my favorite bands, which of course, included my favorite drummers. I was heavily into progressive rock, listening to Genesis, ELP, Yes, Gentle Giant, Crimson and Tull, which soon led to Zappa, Mahavishnu, [Jeff] Beck and Tony Williams, to name a few. Needless to say, I didn't play in many local bands or jam much with musicians in the neighborhood, since no one could, would or had any interest in trying to play songs in 9, 11 or 13, when it was so much easier to learn something from AC/DC or Aerosmith and impress the girls just the same.

I didn't really take to drums until my thirteenth year, but once I did, I quickly made up for lost time by practicing and playing for hours and hours each day. Practicing, for me, was mostly playing with headphones on to all of my favorite bands, which of course, included my favorite drummers. I was heavily into progressive rock, listening to Genesis, ELP, Yes, Gentle Giant, Crimson and Tull, which soon led to Zappa, Mahavishnu, [Jeff] Beck and Tony Williams, to name a few. Needless to say, I didn't play in many local bands or jam much with musicians in the neighborhood, since no one could, would or had any interest in trying to play songs in 9, 11 or 13, when it was so much easier to learn something from AC/DC or Aerosmith and impress the girls just the same.

Enter Neil and Rush. It was 1977, I had just started ninth grade (my first year of Prep School) and before long, ended up playing drums in a rock band full of seniors. AC/DC, Aerosmith, Black Sabbath, Grand Funk, Bob Seger and the likes were the repertoire until I chimed in with, "How about we learn something a little more challenging." Well, seeing that we had no keyboard player, the offer came up to learn a Rush song, to which I replied, "Who?" No, not The Who, but, "Who's Rush?" The next day I was handed a copy of the newly-released A Farewell To Kings, and that was it for me.

It wasn't long before we were playing "Xanadu," "A Farewell To Kings" and "Closer To The Heart" note for note, since I had the concert toms, temple blocks, cowbells, wind chimes, bell tree, tympani and a glockenspiel, thanks to Carl Palmer. (No, he didn't give them to me!)

Well, the icing on the cake came soon after, when Rush played Boston and I got to witness Neil in the flesh. I caught each hit, all his movements and even his facial expressions, while studying every inch of his kit?yes, the 'Virbra-fibed' Slingerlands, Evans Glass and Hydraulic heads, Ludwig Silver Dots, Remo Black Dots and Promark sticks with the gripping area sanded down, ha ha ha. And that was before any, not every, audience member air-drummed every Neil drum fill. Is there any other drummer in history that commands that at every performance?

Anyway, that was my introduction to Neil and to Rush, whose music I've enjoyed throughout many years. Neil's parts and ideas are always interesting and creative, making them and his drumming fun, which first and foremost, is what drumming is and should always be; fun.

Thank you Mr. Peart (pronounced Pear - T), for the many years of drums, music and stories. But most of all, thanks for the fun. - Mover