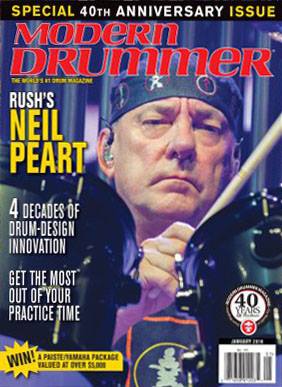

An Interview with Neil Peart

For his (record) ninth MD cover-story interview, Rush's drummer holds a typically fluid and intense discussion of soloing and set lists, the very real differences between his drumming past and present, and the much-speculated topic of his band's future.

By Ilya Stemkovsky, Modern Drummer, 40th Anniversary Issue, January 2016

Say it ain't so!

When Rush announced that its 2015 R40 run would likely be the "last major tour of this magnitude," fans mused about the whys and hows as they snatched up tickets to see their heroes for perhaps the last time.

To celebrate forty years and counting, guitarist Alex Lifeson, bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, and drummer Neil Peart conceived an elaborate reverse-chronology theatrical experience, where over the course of two sets the group would explore its deep catalog, beginning with its most recent material and working backward. Peart would even use two separate setups-his modern, fully realized kit for the first set, and a replica of his legendary late-1970s kit for the epic progressive pieces occupying the second set.

Years after being universally recognized as the world's preeminent progressive rock band, Rush's profile has only continued to rise, with recent documentaries, feature-film cameos, a first Rolling Stone magazine cover, and-finally-induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Through it all, Peart has continued to progress as a player, even though he's got nothing to prove. Now in his sixties, Neil is still devoted to his craft, still hungry, still practicing, still learning, and still expanding his creative boundaries through continued lessons.

"The audience doesn't need to know all the technical stuff," Peart says. "They just need to know that I went through the trouble. Care has been taken. And that's the nature of our band and the nature of each of us individually. So our audience can trust that aspect of it."

Modern Drummer meets Peart backstage in his dressing room at the New Jersey stop of the R40 tour. The drummer greets us and apologizes for being sock-less. He lies on the couch and points to his feet, which look like Father Time-affected, wear-and-tear evidence of half a century of bringing the power night after night.

Sustained Impact

Neil: [After discussing his injuries] At this point in the tour, you have no reserves. So a thing like this attacks, and it wears down your resistance in every other way too. And there's no getting better. I got tendinitis in one elbow on the '96/'97 Test for Echo tour, and then I didn't have it again for fifteen years-and it was the other elbow. For the rest of the tour I have to wear a brace to play, and I wear a brace at night. People say, "Oh, you just need to rest it." Ok, I'll do that. We'll just send these ten thousand people home tonight while I have a rest.

MD: You're certainly not back there playing "Peaceful Easy Feeling."

Neil: [laughs] As you can see, I often refer to what I do as athletic. It's not low impact. And through the teachings of Freddie Gruber, and through my own physical regimen and yoga, I've been able to sustain my peak for a long time and continue to get better and continue to study.

It's a revelation for me that at age sixty-two I can still be getting better and feel it and know it deep down. And move into a new area. Freddie had a transformational effect on my playing. When I worked with him in the mid-'90s, he said, "You're a compositional player." And it's true. My drum parts all through the '70s and '80s were very carefully refined, partly by the nature of the way we worked in those days. We were all in the studio together, learning the song, playing it again and again, and one time I'd put in a little figure or accent and think, This would go with that, and, piece by piece, the architecture, the composition, would come together.

But when Freddie pointed that out to me, I thought, That's nice, but I want to be an improvisational player. So I set out a bit on my own to work more in that direction and to use motifs in my solo and ostinatos that would allow me to expand more. I still have a framework, because I always felt a responsibility to present a composition.

Neil: I loved the way Steve Gadd played "Love for Sale" on the Buddy Rich tribute album that we made [Burning for Buddy], and Dave Weckl playing it live. So I made that my summit. I wanted to aspire to that performance.

Don Lombardi from Drum Workshop and I agreed that Peter Erskine would be the right teacher to take me in a better direction for big band drumming. And he lives ten minutes from me. So I started going to his house for lessons, and he started me on a course of practicing with the Quiet Count feature in Roland's V-Drums brain, which is a metronome that gives you two bars of click, then two bars of silence, and [so on].

So my assignment was to set that to a slow tempo and then a fast tempo and play to it, just hi-hat. And then he gave me some play-along stuff to enhance the feel and understand the swing drumming, people like Sonny Payne with Count Basie. So every single day I sat at the hi-hat and set a very slow tempo. At first?impossible. And I didn't want to keep time [with the rest of the kit].

Practice doesn't have to be tedious. So I never got bored with the hi-hat, for months. I was riffing on it, learning things inside the time strictures and gradually learning to hear what wasn't there: the click. So when those two bars went away, I could still feel them.

Eventually I surprised myself by coming back in on time. The fast ones are a little easier. I've heard from other prominent drummers that when they first tried to do it, it was like, There's something wrong with this thing. [laughs] What it gave me, unexpectedly, was the confidence of time that freed me to be improvisational. Because I could feel that pulse, organically.

Freddie was about motion. He'd say that when you hit the cymbal, it was that, but he also liked these gestures. And Peter had studied with Freddie too. Peter asked me to play quarter notes on a ride, and I was putting in this little curl. He asked what that was, and I told him it was timekeeping. He said, "No," and pointed at my chest and told me the time is there. He wanted me to play those quarter notes with laser accuracy and linear motion. And he had transcended Freddie's teaching, as I learned to. That feeling, that curl that Freddie had put into timekeeping, I intuited it. And I worked on it for months and went back to Peter to play those quarter notes. Like any student, I was nervous about the teacher. And at the end he said, "Perfect," and I was so happy.

MD: Did you feel your internal clock change?

Neil: Rush was on a hiatus and I had a year and a half where I could practice. Later, when the three of us got together, I started putting down drum tracks for the demos. Geddy and Alex said, "Well, it still sounds like you. It doesn't sound any different." And I was kind of disappointed. But when they went to play with it, it was completely different. The clock had just changed, altered that much. And that remains to this day. If we revive one of the older songs from prior to that time, I play it as I would play it now.

One song we revived, "Presto," we play so much better now, and Geddy said, "We have a different clock now." So they got it. There was something fundamental and seemingly intangible, because they couldn't hear it. It was more of the freedom now.

On the last two Rush albums, I haven't composed the drum parts-I've performed them. We worked with producer Nick Raskulinecz on the last two records, and I would play through the song a few times, see what would work, and then he'd come in and we'd start recording. And he would conduct me, because our arrangements can be obtuse, and it used to take a long time for me to learn them.

I used to say it took me three days to learn one of our songs and put together a drum part. I don't like to count. I don't like to write notes. I want to play this thing like music. On this tour we're playing a lot of our older stuff from the 1970s with bizarre times. Why did we do this stuff? Because we were kids. We were learning how to do it. Because we could. I play that stuff completely differently now, with a much better lilt and feel and natural flow.

MD: In your last MD interview, in 2011, you said that studies with Gruber and Erskine helped you retain accuracy but feel good inside. Has anything changed? Is that even better now?

Neil: I'm still evolving in the ways that they have guided me. Sometimes I'll do an interview with non-musicians and they'll ask why I practice so much and take lessons. Well, I have the privilege of being a professional musician. It's my responsibility to devote myself to being all that I can be to the people that have given me that opportunity.

MD: Not everyone thinks that way.

Neil: I know, but they should. [laughs] I live by example. As a drummer, set a good example and don't work the audience. And when other drummers tell me I've inspired them to play drums, I tell them to apologize to their parents. [laughs] Like for this tour, I started preparation three months earlier. I'd play along with tracks all day and work on solo ideas, five days a week. So by the time we get to band rehearsals, I'm ready.

MD: How did the reverse chronological order of the set list come about?

Neil: Alex and I were excited to find the deep tracks, the songs we never play live. And we wanted to do a theatrical presentation where the show devolves back in time. So then we started thinking of how the songs should be chosen, and you've got two responsibilities-set one and set two, like two sides of an LP. So they'd have to start and end somewhere, and carry the audience dynamically.

Years ago we were talking about a certain order of songs, and Alex said we couldn't do that because they were all in the same key-something no one would think about. And I'm conscious of that tempo-wise. And for Geddy as a vocalist, he might not want to sing certain songs in a row.

A Tale of Two Kits

MD: Let's talk about your drumsets on this tour.

Neil: The kit in the first set evolved as an instrument of perfect comfort. I can play it with my eyes closed. The musicality through the cymbals and the toms. Everything is carefully chosen and put where it should be. I tell people: Don't look at those forty-seven drums. It's a four-drum setup. Look at the middle-everything spins off from there.

In the '70s, things evolved from the '60s. Ginger Baker [Cream, Blind Faith] had his ride off to the side with a crash on top of it, so he could have three or four toms across the front. That's around the era when I started playing, so I gravitated that way. When I first switched to the double pedal in the early '90s and DW really refined the first proper double-pedal setup, I went to it willingly right away-just ergonomically to free up the space. But I couldn't believe the sonic aspect. At the time, I half-noticed that the toms sounded cleaner and everything sounded more discrete.

This second kit was modeled after my 1978 black chrome Slingerland set. I had the notion that wouldn't it be great if, instead of having the rotating set I've had for years that kind of contrasts the acoustic and electronic drums, I went to a whole second drumset. I went to Drum Workshop and said I wanted that exact setup.

I always say this about old cars and motorcycles, and old drums: I love them, but new ones are better. There's no argument. And both sets are made from one tree in Romania that fell in the river, got buried in silt, and lay there for 1,500 years. In 2014, John Good from Drum Workshop bought that tree and made a few prototype shells that I tried. Of course the wood gets super-dense over that time, with pressure. And the resonance and timbre of the note were superior to even the best shells DW makes, which have evolved over my twenty years with them. And playing two bass drums and open concert toms again was fun.

MD: Was it tough at first to play that old setup again?

Neil: It was tough. The ergonomics of it all. I used to make everything so close and under me. But it was counterintuitive thinking. I used to think the closer it is, the more power I can get on it, but that's not true. You have to get it the right distance. Close or near doesn't matter. And the way the set list works out, I had to solo on that set. I'd much rather solo on my modern set in every sense, musically and physically.

But there are cool things as well. I used to have timbales on my left side, so I got those again and they're fun. That's part of the solo. But it grew organically and naturally by what excited me to play. And I never practiced this solo the way that I used to. I used to really compose the solo, and this one never went that way. And there are things in my solo that have been there since I was sixteen, that always thrilled me and still do.

MD: The snare stuff.

Neil: Yes, I can vamp on a snare drum all day long. And the four-on-the-floor. It feels exciting to me. And in the solo it's all spontaneous. There are places I like to get to, like the waltz, because I love that. And I'll go up on the concert toms over the waltz, because I like how that works. And I want to get the cowbells in because they're funny. And there's a little Brazilian ostinato I love, though it's not in there every night.

MD: I'd figure you'd have the fearlessness to improvise a solo like that back in the day, but you're doing that now, later in the game.

Neil: I didn't have that fearlessness. And it was a responsibility thing. I wanted to make sure the performance was consistent. And I don't want to use tricks, but tools. There's a very important distinction. The quarter-note bass drum can be a terrible cliché. But if you use it at the right time in a complicated arrangement or something, there's nothing more powerful. I don't ever abuse it.

To me, my solo has become a soundtrack to an imaginary movie. When I want to build up the excitement, it has to be organic. When I build up that rudimental snare part and I bring the bass drum in, as soon as I start stomping on the hi-hat, it starts glancing, it's more exciting, and it's more exciting to play.

And for years I had 13? hi-hats, clamped down tight. Peter Erskine said he used to be like me-he had his hi-hats super-tight and super-controlled. He said to just try to let them slosh for a while and see what happens. I did, and sure enough I learned that when they're moving like that, your velocity has to be exactly right and it helps your time sense. I got used to it, and it has this whole other benefit. Like in "Roll the Bones," the part with the sloshy hi-hat. I play that so much better now, and the feel in my bass drum foot is so much better for the quick hits. As is the time control, because I have to play to that moving hi-hat. Rhythmically, the velocity of my stick affects when it's coming back and the interval in between. And it's funkier. It's not just a sloshy hi-hat-it's part of the time.

MD: It's a shame you can't have all this fun on the kit you'd rather be playing.

Neil: Old things are nice, but new things are better. And I just know so much more through all the learning and evolution. The newer kit is just such a comfortable instrument, while the second one is ad-hoc. It came together bit by bit. Playing it now, I have to sit at it differently. My posture. And think about it and look where I'm going. The first time I tried to hit crash cymbals without looking, I was bleeding. And very many times I would finish something and go to where the ride cymbal should be and there's a tom there. So the map is different.

But I was able to compensate. It's not a compromise, it's a limitation, and one that I decided on for all good reasons. And I noticed quite a few of the songs had chimes. I have that as a sample on my malletKAT, but I thought, You know what: Real chimes-it's suitable for the theater. Century Mallet in Chicago made these beautiful-sounding black-nickel chimes.

The one factor that connects all this is the second bass drum. All the toms sound muddy on that side. And I'm told by the sound guys out front that a good thing is the main bass drum resonates in the other one, and it gives it a certain sonic quality out front that's all right. But it's the little subtle things like that that are a challenge.

Making Trades

MD: You've been celebrating the fortieth anniversary of the band on this tour. How do you choose what to play?

Neil: We don't have any songs that we hate, and there's none that we get sick of. They all have their charm to us, because they were all written from the heart, so there's none we feel reluctant to play. We came up with alternate sets, so it allowed us to not have to drop things but just play them every three or four shows. And that served us well on the last tour, and it was the first time we dared to try that. We usually hesitate to take on more work than we need. [laughs] And that's true even on the records. We've never written and recorded a song that we didn't put out. Why go through all that trouble?

Our benchmarks are really organic ones. I always think if I have a good idea, I'll remember it. If we play something that we like, we'll remember it. So there were songs that never got played, for one reason or another. We also wanted to fix on what we thought were high points along the way dynamically. But all the ones in the first set are killers to play, physically.

MD: They look demanding on you, right away.

Neil: On an album, you'll typically have a couple of slower, easier, gentler songs. But live, we don't. So it's an hour sprint for me. Full power from me.

MD: So if you never played "Limelight" again, that'd be okay?

Neil: Yeah, we've done it. We still like it. And there were lots of songs like that. We said, "Let's do this instead." We had to make those kinds of trade-offs.

MD: With your new feel and clock and maturity, do you ever think about how you might do something differently from

these iconic parts and fills that you wrote long ago?

Neil: I do play those songs very differently. I've evolved into a different, more improvisational player. The clock on "Tom Sawyer" or "The Spirit of Radio" now?they're very different from what they were. I'm happy to play the composed parts the same every night. "Tom Sawyer" remains that way. If I can play that right every night? Fine. I don't change very much, and I don't feel like I want to. "The Spirit of Radio" is another great example. Since 1979, I don't think I've changed anything except the feel.

For songs in those days, we were just starting to do a very formative technical thing, which was to put sequencers in the middle of a song. For that song, I'd have to play the intro and the first verse, which already have two different tempos, and then get to the chorus, with that sequence [sings the synth part], which was going to be the same every night. But I learned from that, to get set up and to get there and to flow through it and out of that. At the end, this piano sequence comes in, and typically toward the end of a song you might be speeding up-that's human nature. But I had to learn to train myself to know that thing is going to be coming in, and I want that to feel great. That should be the lift; that can't be the drag. So my time feel on those songs is that subtle difference that doesn't sound different but absolutely feels different to play, and better to play.

The Nature and Nurture of Change

MD: Back in the day you were part of a movement of idiosyncratic drummers who had a "sound." Stewart Copeland, Billy Cobham-if those names were on a record, it was going to sound a certain way. Guys who imposed brilliantly on the music, like Jack DeJohnette.

Neil: One of the masters. I've said of Jack that he's the one who best bridges classic drumming and modern drumming.

MD: Beautiful player, but he's not going to appear on a Katy Perry pop session.

Neil: [laughs] Let's hope not.

MD: And country records all sound quantized. Is it a healthy time for drummers? Where's the individuality? Where is the instrument going?

Neil: It's difficult. We were rehearsing in Toronto and I was driving back and forth and made it a point to listen to Top 40 radio. And it was fine. I love the R&B/hip-hop combo-it's very healthy for what it is. And I've always loved pop music if it's honest. Don't pretend you're a rocker in a leather jacket if you're a pop star. What is pop short for? Popular. It's not the same thing as being in a rock band, where I think a certain amount of integrity is inherent with the definition.

Over the two weeks, I didn't mind the music, but I did not hear one drummer or one drum. But all of these acts have real drummers live, because the difference on stage-the theater of a live drummer-is enormous. The hope for the future is as performing drummers. It's hard to encourage young musicians now, because my rote advice is so useless, because I say, "What you have to do is play live." When I was a kid, we used to get gigs at the high school or the roller rink on the weekends, and during the week I could get paid $20 to jam at the coffeehouse with other musicians. There were a lot of opportunities to play live if you were willing to ride in a van and pay your dues that way. There's no better way to learn.

For this band, when we got together in 1974, when we went out opening a tour, if the headliner took a day off we would go back to Akron, Ohio, and play the club. We would play anywhere and do anything. It was a slow build, and we worked so hard as an opening act. We were all supply and no demand. So later, when the demand grew, we eventually had to learn to say no. To not play ten shows in a row. Those were lessons along the way.

But we had the opportunity to play, and together. First, to build that unity, and then, over making subsequent albums, to learn how to write and arrange songs, and to learn to play and have a thing like "La Villa Strangiato (An Exercise in Self-Indulgence)." We knew what we were doing. Yeah, we were playing all this stuff because we could, but that's what we were supposed to do.

MD: Your music demanded the audience to invest in it.

Neil: We built our enduring reputation by live performance. Our albums would sell up and down, but people would still come to the show: "I didn't like that album so much, but I know that they'll play the rest of them, and the show will be good and they'll give it all they have." There was a trust factor there. So that's the hope for the generation of the future-the passion for the instrument. That people would want to play, whatever it takes.

And now people are finding avenues to communicate their music other than coming up through clubs. Not to publicize it or to brand it or sell it, but just to get people to hear it. If a band can get heard and seen on YouTube, then they can get gigs and start playing live. It's different, all right, but I still see people making it.

The Write Way

MD: You've said that sometimes you'll change lyrics so that Geddy can sing them more easily. Do you ever collaborate on the rhythmic delivery of the vocals?

Neil: Yeah, we often discuss phrasing. Plus it's kind of in-built. I have an advantage there, in that words are always rhythm to me. A line comes into my head and it has a rhythm, automatically, because I hear it as a drummer and pattern my phrasing that way. But sometimes I'll take liberties so that one should be longer and the next one should be back-phrased. And I might explain that to Geddy, or when he's doing his vocals I'll be around and if I hear him having trouble, I can rewrite something.

MD: And he's open to your suggestions?

Neil: Oh, mostly asking for help. [laughs] "I'm having trouble with this line" or "I need two more lines like this." Great-I can do that.

A lesson I learned is not to try to write one whole song and give it to the guys, like, "Here's my precious masterpiece." I just write a whole bunch of stuff and give it to them. They'll sit and jam and record it all, and Geddy will sift through it and make an arrangement out of it. And when he likes lines, I'm inspired. Just the fact that it's been accepted and found worthy to be a song. If anything gets rejected or left out, it's not a negative.

"Caravan" from Clockwork Angels is a good example. We had the "I can't stop thinking big" line. Geddy made it into the chorus and asked if he could have one more line to wrap it up. And somehow it came out to be "In a world where I feel so small, I can't stop thinking big." I don't know where that came from. It was just spontaneous.

It was a puzzle to solve. I'm really good at crosswords, and that helps a lot with that kind of thing. I have this many syllables. A song, even in our case, without much repetition, is only a couple hundred words. So you have to become super-economical with them and choose the word that conveys the meaning the best and that sounds the best being sung, and that bears repeating. I didn't write "I can't stop thinking big" to be repeated. It was just a line. That's one example where the problem solving can suddenly be inspiring. I don't know where that came from, but thank you. [laughs]

MD: What's more gratifying, seeing fans singing your lyrics or seeing them air drumming?

Neil: Singing. One of the keys to our longevity is that I know in many bands there's a great envy of the singer for getting all the attention. It causes a lot of ruptures and conflicts and all this pure ego. But all these people singing along with Geddy, they're singing my words. How can I feel bad about that? So that's very gratifying.

And the air drumming is the same thing. It's a level of engagement, just sheer exuberance. That's the energy you feel. It's truly spontaneous and it's a feedback loop. We energize them and they energize us. It's a palpable, sincere thing, and it's not just about [the musicians] putting on a show, but [the audience] being in the show. And I always say, I am the audience. I'm not a performer by nature. The choice of drums drove me into being a performer. I'm really a one-on-one talker. When I'm on stage, I watch people a lot. And the world too-on my motorcycle rides on my days off, it's the show coming at me. I'm the audience for it, and I try to absorb it as deeply as I can and hopefully share it with others later.

And that's the big appeal with prose writing, the urge to share. And this just occurred to me, but I bet the excitement I get in playing particular songs of ours [comes from the fact that] it communicates, "This is real." The energy that I'm giving this, the fact that this excited me when I recorded it and that became the drum part I wanted for that song-that meant something, and it still means something.

MD: Induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the cover of Rolling Stone?what's going on here?

Neil: [laughs] Persistence! Just keep going. You can eventually earn people's respect. It's easy to be dismissed in the beginning. And I've done that myself as a reader. Just dismissed certain writers. And then they earn my respect over time. That's persistence.

MD: What's in the future? If Rush isn't touring, will you still record? Write prose? Be a dad?

Neil: You just answered it. There's no strict answer, but those possibilities are all there.

"El Darko" Kit

Drums: DW shells made from Romanian bog oak with black chrome finish

A. 6.5x14 VLT snare

B. 6" concert tom

C. 8" concert tom

D. 10" concert tom

E. 12" concert tom

F. 8x12 rack tom

G. 9x13 rack tom

H. 12x15 rack tom

I. 16x18 floor tom

J. 5x20 gong drum

K. 16x23 bass drums with

Kelly Shu miking system

L. LP 13" brass timbale

M. LP 14" brass timbale

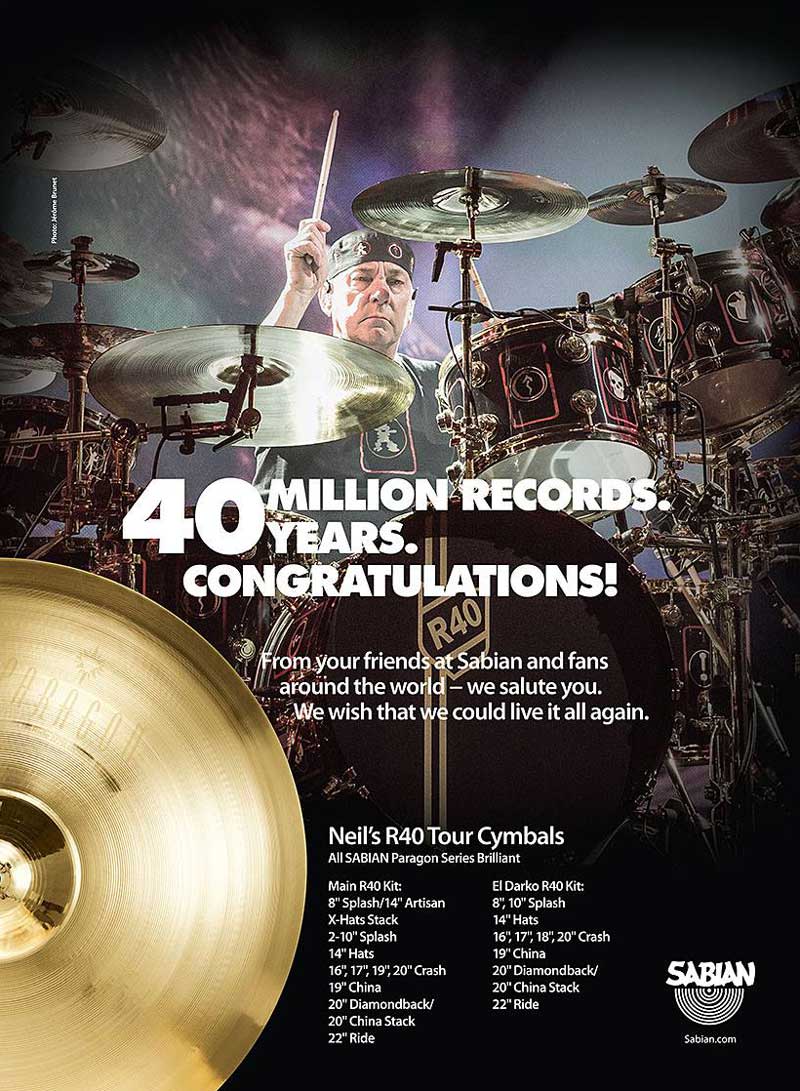

Cymbals: Sabian Paragon with brilliant finish

1. 20" crash

2. 17" crash

3. 14" hi-hats

4. 10" splash

5. 16" crash

6. 8" splash

7. 18" crash

8. 22" ride

9. 20" Diamondback

10. 20" China

11. 19" China

Percussion

aa. Gon Bops Cowbell Tree

bb. Century Mallet

orchestra chimes

cc. malletKAT Express

Hardware: DW 9000 series bass drum pedals and stands and 5000 series hi-hat; all stands with black nickel finish

Sticks, Heads, Extras: Peart plays Promark 747 NP "R40" signature model sticks. His heads are "an ever-changing variety of DW and Remos," while his accessories include UrbannBoard NP Signature Drum Shoes and Whirlwind braided cable. Neil's drum tech is Lorne "Gump" Wheaton.

"R40" Kit

Drums: DW shells made from Romanian bog oak in Dyed Black Pear finish

A. 6.5x14 NP Icon snare

B. 13x15 floor tom

C. 3x13 piccolo snare

D. 7x8 rack tom

E. 7x10 rack tom

F. 8x12 rack tom

G. 9x13 rack tom

H. 12x15 floor tom

I. 16x16 floor tom

J. 18x18 suspended floor tom

K. 16x23 bass drum with Kelly Shu miking system

Note: Each of the drums' logos, as well as the red oblong frames around them (which deliberately evoke Keith Moon's "Pictures of Lily" kit), are made of inlaid hardwoods.

Cymbals: Sabian Paragon with brilliant finish

1. 10" splash

2. 20" crash

3. 14" hi-hats

4. 17" crash

5. 10" splash

6. 16" crash

7. 22" ride

8. 8" splash

9. 14" Artisan hi-hats

10. 19" crash

11. 20" China

12. 20" Diamondback

13. 19" China

Electronics:

aa. Roland TD-30 trigger pads mounted in DW shells

bb. custom-built Dauz trigger pad (the "target" head is a Who reference).

All trigger samples processed with Ableton Live.

Hardware: DW 9002 series double bass drum pedal and 5000 series hi-hat; all stands with gold-plated finish