Neil Peart: "Suddenly You Were Gone" - "Hail The Professor" - "Making Memories" - "Force Ten" - The Enigma of Neil Peart"

By Philip Wilding, Chris McGarel, Tim Ponting, Gary Mackenzie, and Martin Kielty; additional research: Malcolm Dome, PROG, February 2020, transcribed by John Patuto

Editor's Letter

It's not the ideal way to start your first issue of the year, but alas, we say goodbye to one of the greatest - if not THE greatest - drummer the prog world has ever seen: Neil Peart. Sadly, Neil succumbed to glioblastoma on January 7, and although he retired from Rush, the band he was solely linked with during his life, in 2015, I'm sure I was among many fans who hoped that one day we might see the great man and his two long-standing bandmates and friends back onstage together in some way. Now, of course, that will never be.

Like many of you, I was stunned by the news. I don't mind admitting that on Saturday morning I put on my old vinyl copy of Fly By Night, Neil's introduction to the world in Rush, and welled up. I was fortunate enough to see Rush play live many times, and thanks to my involvement with music magazines over the past 30 years, have some small interaction with the band on the odd occasion. They remain one of the most unique and dignified of acts, a fact that comes across in the way they've continued to go about their business for more than 40 years.

Nothing magnifies that point better than the fact that no news broke of Neil's passing for at least three days - quite astonishing in this digital age of rolling news, but wholly in keeping with this private man who largely shunned the limelight, despite being a member of one of the music world's most successful acts. "He lived his life his way, never afraid to be himself, encouraging others to be themselves too," is how one-time Boston DJ Donna Halper, who helped break Rush in the US in the mid-70s, described Peart. A better summation you're unlikely to find.

So this issue we pay tribute to the late, great Neil Peart. We've called upon our writers who best understood Neil, his music and his lyrics, to honour this greatest of musicians and men. I hope you feel we've done him proud.

To Neil Peart. R.I.P.

Neil Peart Passes Away At 67

Prog bids a sad farewell to one of drumming's kings.

Rush drummer Neil Peart died on January 7, aged 67, after an unannounced three-year battle with brain cancer.

He'd brought the Canadian trio's career to an end in 2015 when he retired, citing damage caused by years of his "athletic" approach to playing, and his desire to spend time with his family. Reports suggest he was diagnosed with gliobastoma in mid-2016.

Rush bowed out after a career-spanning 35-date tour. "Honestly, people don't realise the sacrifice you make as a touring musician," Peart told sister mag Classic Rock in 2017. "Being away when children are growing up and when your partner needs you around, it's wrenching. Your family and friends, their lives continue and you're not part of them."

Their last studio album, Clockwork Angels, was their 19th and released in 2012. Peart had appeared on all but Rush's 1974 selftitled debut LP, and helped the band notch up 24 gold records and 14 platinum.

Peart authored seven non-fiction travelogue books, notably 2002's Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road, where he documented his motorcycle trip as he tried to get over the death of his first wife and daughter. He also co-wrote two books based on the theme of Clockwork Angels. He appeared in five drumming DVDs and produced several tributes to his hero, Buddy Rich.

Announcing his death, bandmates Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee described Peart as their "soul brother" and asked for memorial donations to cancer charities.

Suddenly You Were Gone

By Philip Wilding

Nobody knew Rush quite like Prog writer Philip Wilding. In the wake of drummer Neil Peart's sad death from brain cancer he shares his memories about what made the man so very special.

There are no other vehicles out on this highway, the light fading from the sky as a motorbike pulls into view, a lone rider casting a long shadow, there briefly in focus and then gone, heading to the horizon, going nowhere and headed anywhere. "He'd gone," Geddy Lee told me years later, years after Neil Peart had lost his 19-year old daughter Selena in a single-car accident as she drove to her university in Toronto. That had been in the August of 1997; five months later his common law wife of 23 years, Jackie Taylor, was diagnosed with terminal cancer. After her death, Neil told Rush to consider him retired and took to the road.

"We didn't know where Neil was," said Geddy. "He was just out there somewhere and then very occasionally we'd get these coded postcards that we knew were from him, and that he was alright."

Neil finally came back to the band to make Vapor Trails and tour again in an era of Rush that Lee calls his very favourite. Perhaps even more remarkably, the man who practised his drums for hours every single day of the year apart from Christmas Day, hadn't even touched his kit in all the time he'd been away. As the band were putting themselves back together, guitarist Alex Lifeson would stay late after Geddy had left for the day. "And me and Neil would just jam together, get his chops back up, stay late and play."

Neil joined Rush in 1974 after the departure of original drummer John Rutsey. "I remember him pulling up and unloading his gear and we thought he was kind of goofy looking," said Lee. "And we thought we were pretty cool cats! But he started playing and Al and I just sort of caught each other's eye. He was astounding, he blew us away. After he left this other guy turned up and he was setting up with his sheet music and I felt kind of bad for him because after Neil's audition he had absolutely no chance."

Neil walked away from Rush in August 2015, as he began to doubt his ability to play to the demanding high standards he set himself. He had another daughter now and a new wife, and he, more than most, must have realised how time is fleeting and we need to hold on to what we love when we can.

I was at those last few concerts with the band, watching their penultimate show at the Irvine Meadows Ampitheatre in Orange County, California from the side of the stage. Not only to enjoy the frantic air drumming and faces pulled by the startled onlookers in the first few rows, but to watch Neil up close, to try and fathom what exactly he was doing.

It was impossible, though. His reddening face was almost impassive, his signature hat perched on his head - how it stayed on in that maelstrom is still a mystery for the ages - but his arms and legs were doing impossible and strange things. Each fill was a recognisable moment of wonder and I, along with every other human being in that open-air arena, paused to get the air drum fill on The Temples of Syrinx just right. There was something joyous and gloriously unhinged about 16,000 strangers all caught up on the hook of that thundering drum fill rattling across the toms. I'm pretty sure we all thought we were in time too.

It was that tour, and one I wish more people could have seen, where the setlist was played out in reverse chronology, starting with songs from Clockwork Angels and ending with Working Man, the stage stripped back to resemble a high school hall, some hours later. Given that the band had to work backwards through their catalogue, Neil had two separate kits around him, his latest set up front and then, as the set progressed (or regressed depending on your viewpoint), the drums would switch around to reveal one of Neil's older kits from another tour and another time.

The older kit was harder to play and less comfortable and less conducive to the setup Neil had grown used to, but he - and this was very Neil - insisted on soldiering on with the older kit for half the set as it brought authenticity to the music. That's how those songs had been played live before and they would be again.

But I'm getting away from myself; my head is filled with images and memories of him. Drinking 12-year-old Macallan with him at the mixes of Clockwork Angels; him showing off his beautiful silver Aston Martin (as driven by James Bond in Goldfinger), one of many; standing at the Canadian consulate with him in Los Angeles; Neil laughing with the actor Jack Black as they stood out by the pool. Jack looking quizzically up at Neil. "I mean," he said, "this is officially Canadian ground, but we're in LA, so, technically, right now, are we in Canada or not?"

But that's not what I'm trying to tell you. I'm trying to tell you that, as I stood side of the stage and watched him rattle around that impossible drumkit, I could see no weakness in his playing. Rush didn't feel like some fading power, a band that needed to be stopped before the real lustre was gone, but Neil felt that something was missing in his game, and like his playing of a vintage kit that didn't quite suit his needs anymore, he understood that stopping was the right thing to do.

I was standing on the roof of the London West Hollywood Hotel in LA, under the blazing Californian sky, people in the pool splashing around behind me, the snaking traffic pulling away towards the horizon. I was waiting for the last show and hoping against hope that Neil would somehow change his mind (I wasn't the only one - Ged clung to the same forlorn hope for a few months afterwards) and that night's performance at The Forum in Inglewood would see a shift in how the band worked - fewer shows, more one-off live events - and not the end of the road. I fell into conversation with someone who worked with the band: at the end of each tour, Neil's drums, not the ones he kept at home in California and gave merry hell to almost every single day, but his touring drums, would go back into storage in, as I recall, Nashville. This one last time, he'd asked that they went home with him. I wasn't even sure of validity of the story, it sounded apocryphal, too neat somehow, but there in the glare of the Hollywood sky it hit me hard. I felt winded: this was the last Rush show for now and for ever.

That thought was compounded that night. For the first and last time, at the end of the show (one of the most complete and spectacular shows I have ever seen the band play) and with the sound of a frantic Working Man still ringing in our ears, Neil stepped down from his drum riser and crossed to the front of the stage to embrace a very surprised-looking Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson. The three embracing as the lights came up, he was saying goodbye to us then, the room felt it, his arm raised in salute to the 17,500 audience, each of us willing him not to leave us, not to leave Rush, but there was the impish grin and he was gone to the shadows and to another life.

That grin. He laughed a lot - more than you might think from his stony countenance or that drilled concentration when he rolled around his drums. He was very close to the South Park creators, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, both of whom were at that final LA show. You only have to check out the extended cut of the brilliant Beyond The Lighted Stage to watch him almost lose consciousness with glee as he turns tomato red and gasps helplessly as Alex keeps the zingers coming until poor Neil is practically on the floor begging him to stop. He laughed well, head back, his looming frame shaking with that self-same laugh.

I made him laugh once - heard and saw that happy exultation - and in a moment where I was trying to do anything but make him laugh. Rush were playing the NEC in Birmingham. It was 2007, their Snakes & Arrows tour. Pegi Cecconi, a long-time friend and associate of the band, and I travelled up from London to see them play. For some reason on that tour Geddy had foregone any usual sort of backline and had settled on a row of chicken rotisserie machines. During the set a roadie would be sent onstage to baste Geddy's chickens, which sounds far filthier than it was. It came as a complete surprise to me when I was forced onstage in a pinny and chef's hat - it was that or something that looked like a rubber chicken so I opted for the hat. Armed with a basting bowl and brush, I was pushed up the surprisingly steep stairs to the stage.

To compound my fear and confusion, Rush had just broken into The Spirit Of Radio, a single I remember buying as a teenager one Saturday morning back home in Wales. So, no pressure then, all of this manifesting itself in my frontal lobe, as Alex pealed out that extraordinary riff out into the dark and cavernous NEC hall. The stage was huge, like a football field covered with amps and drums. To my right and just off stage, Pegi could be heard laughing out loud from the shadows, screaming my name in a way that I'd like to think was done with at least some affection.

I basted Ged's chickens with due diligence, opening up the smokey glass rotisserie doors, adjusting the heating knob and moving along the stage. It was only then and out of the corner of my eye, that I caught sight of the furious, pumping machine that is Neil Peart up close. His legs were like pistons, arms a familiar blur, his face stony with concentration, he looked like a steam train that was locked in place. And then, just as I reached the last rotisserie, he turned his head towards me, burst out laughing and exclaimed: 'Phil!' His metre didn't shift, not a fill missed, but there, just for a moment, in that swirling darkness punctuated by pulsing stage lights, he grinned and looked at me like he'd just caught me stealing apples in his yard. It was a moment of such beauty and stillness that it still makes me pause now. To be there then, in that moment, happy to have stood briefly in his light, but the memory of that laughing face, his dizzying skill now gone forever, makes my heart break over and over.

Absurd now to think that his energy is stilled and gone forever. I'm furious at the universe for taking him away from us, that something called glioblastoma (an aggressive form of brain cancer), should have diminished all that power and eventually his light. His warm and generous energy snuffed out, his intangible skills finally stilled. I'll leave you with this: we were talking once, Neil and I, for some longforgotten interview. And as was often the way, the subject of his wanderlust and unique way of touring - transporting himself to the show on his motorbike and meeting the band at the venue - came up.

"I love what the bike gives me," he said. "The injection of life, freedom, engagement with the world, and it's still something that I love: the anonymity I have on the motorcycle. I stop at a diner or at a gas station, I have wonderful encounters with people at rest areas at the side of the road... these moments that are just person to person. Those are the moments, that is how I live best."

And that's how I like to think of him, still out there somewhere. A moment of grace in another person's day, thumbing through a batch of postcards in a corner store, wondering which one to send out into the world next, to let us all know he's okay.

Hail the Professor

By Chris McGarel

"Rush constructed who I am," says Chris McGarel. It was Neil Peart's beautifully crafted words that inspired the Prog writer to eventually study for a master's degree in English Literature. Here, he explores the lyrics of one of prog's finest poets and selects some of the most evocative.

Neil Peart's place in the pantheon of rock greats was secured by his innovative drumming but no less awe-inspiring was his proficiency as a lyricist. A voracious devourer of the written word, his knowledge spanned from the classical era through the literary canon to non-fiction that embraced every subject under the sun, and beyond.

Here are just 10 of his best lyrics.

Anthem, Fly By Night (1975)

Beneath, Between And Behind was the first lyric to fall from Peart's pen but it was Anthem that the world would hear first. The lead track from Fly By Night announced a new Rush with a thunderous call to arms. Inspired by Ayn Rand's novella of the same name, Anthem is a hymn to individualism ('Live for yourself/There's no one else more worth living for') and opened a seam that would be mined to its depths on the epic 2112, causing controversy and prompting Peart later to distance himself from Rand's philosophy. As an opening salvo, Anthem hit its target.

The Trees, Hemispheres (1978)

This pastoral parable of oaks and maples would also court controversy. A childlike, Tolkien-esque tale of anthropomorphism takes a sinister turn as the trees of the forest are kept equal 'by hatchet, axe and saw'. The genius of The Trees lies in its literary simplicity, masking its political allegory in the plain language of fable. Its perceived anti-Communist message ('So the maples formed a union/And demanded equal rights') would prompt some to lazily dub the band "crypto-fascist", a label Rush struggled to shrug off for some years.

Freewill, Permanent Waves (1980)

The theme of individualism would resurface in 1980 with Freewill. Again the lyrics work on multiple levels, alluding both to self-determination and agnosticism: 'You can choose a ready guide/In some celestial voice/If you choose not to decide/You still have made a choice.' The drummer articulates a musicality that few lyricists can muster - the sound is as important as the semantics. Its lines are littered with alliteration: 'phantom fears', 'kindness that can kill', 'victim of venomous fate', 'planet of playthings'. Words were Peart's playthings and he was having fun with this one.

Limelight, Moving Pictures (1981)

One of Rush's most recognisable songs thanks to Alex Lifeson's classic riff, Limelight is a half-cautionary, half-celebratory warning from the front lines of celebrity, reflecting as much on our desire for fame as on Peart's own unease living in the camera's eye. 'All the world's indeed a stage' riffs on Shakespeare and on the title of Rush's 1976 live album. As with Hamlet, appearance and reality are set in opposition ('Those who wish to seem/Those who wish to be') in a catchy chorus that belies the complexity of the philosophical question within. Yes, Rush could rock while referencing Bertrand Russell and Elizabethan drama.

Subdivisions, Signals (1982)

Urban planning is an unlikely basis for a rock song but Neil Peart forges an anthem for disaffected youth. The chorus: 'Conform or be cast out' has chimed with millions around the world. If 1981's radio hit Tom Sawyer caricatured the aloof swagger of a teenage rocker, then Subdivisions captures the stereotypical Rush fan: the misfit or the class nerd, unsure of themselves and of their place in the world as viewed from labyrinthine and sterile suburban sprawl. Peart's deliberate overuse of rhyme captures that mundanity and frustration: 'Any escape might help to smooth/The unattractive truth/But the suburbs have no charms to soothe/The restless dreams of youth.'

Between The Wheels, Grace Under Pressure (1984)

Grace Under Pressure contains some of Peart's best writing. Its eight songs capture the 80s zeitgeist of Cold War paranoia, holocaust (both nuclear and actual), societal fear and the loss of individual identity through technology. The summation of these concerns is Between The Wheels, a song even more relevant now in the age of rolling news saturation ('Soaking up the cathode rays'; 'Bright images flashing by/Like windshields towards a fly.') Economic depression and dystopian future are juxtaposed against the American Dream: 'We can fall from rockets' red glare/Down to "Brother, can you spare?"/Another war - another wasteland/And another lost generation.'

Territories, Power Windows (1985)

The dangers of nationalism are tackled in Territories, another song that seems more relevant today than in 1985. 'Better the pride that resides/In a citizen of the world/Than the pride that divides/When a colourful rag is unfurled', Peart writes, railing against the tribal 'drunken and passionate pride' whipped up by populist leaders. Why invade other lands? he asks, when you'll inevitably be complaining about the home comforts you left behind: 'Better people - better food - and better beer.'

Mission, Hold Your Fire (1987)

An insight into Peart's creative process, his striving for perfectionism. He describes experiencing art and longing for the ability to conceive those paintings or music or architecture: 'I wish I had that instinct/I wish I had that drive.' As in Limelight he warns about the 'exotic and strange' life of the creative individual: 'We each pay a fabulous price/For our visions of paradise.'

Dreamline, Roll The Bones (1991)

Wanderlust is a recurring theme, as evidenced by Peart's many travelogues. In Dreamline he observes: 'We're only at home when we're on the run.' The song is a metaphor for searching for something better. Better food? Better beer? Perhaps, but also the better self. Dreamline speaks of physical journeys as well as the roads we travel as people, of dream realisations, escaping the suburban maze, or the banality of 'Middletown', or hitting the trail like a ghost rider. 'We're only immortal for a limited time' is a witticism worthy of Wilde or Twain.

The Garden, Clockwork Angels (2012)

Clockwork Angels is Rush's only concept album. It's a sci-fi steampunk story but it's difficult not to read its final track as autobiographical. 'The arrow flies while you breathe/The hours tick away/The cells tick away' are the words of someone facing their mortality and looking back on their life: 'The treasure of a life is a measure of love and respect.' Neil Peart earned ours.

Making Memories

By Tim Ponting

At the tender age of 22, I encountered for the first time a human being who smoked faster than me. He also played drums faster than me, and by all accounts better than me, and everyone else. In Modern Drummer Magazine's influential yearly poll, he won 'Best Rock Drummer' in 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984 and 1985, and then in 1986 they invented the 'Honor Roll' to make him ineligible for the annual award and ensure he didn't win it every year until 2112.

As a young journalist on Rhythm Magazine, to me Neil Peart was God. I met him in person once only, in a cavernous room at the Mayfair hotel on a damp Friday in April 1988, the morning after Rush's first gig at Wembley Arena since the New World Tour of '83.

A nervous PR seemed slightly taken aback at my dishevelled state (I had failed dismally to sleep on a friend's floor in Streatham after the gig) as Neil shook my hand and then lit a cigarette, a procedure he repeated every four and a half minutes for the next hour and a half. He smoked for Canada.

I remember I mumbled something about enjoying the concert while setting up the tape.

"Last night was a good one, you don't always feel good about it afterwards. But last night was... comfortable." Puff. Draw. Pause. I fumbled with the cassette. "All of us were comfortable and relaxed." The aforementioned PR frowned as trembling, I lit my own cigarette, a poncey St Moritz with a gold band. We proceeded to puff together like a Commonwealth all-star synchronised chain-smoking team.

"We go home from here and start sifting through the performances, looking for a live collection," he explained. "The nature of it we're not quite sure yet: it depends on what we find when we start listening back. It's something that can encompass three tours and thus could form quite a nice anthology. We also filmed two of the shows up in Birmingham, and I know the second of those two we also recorded a really good performance - perhaps something will come out of that."

It did. More than half of 1989's A Show Of Hands' live set was taken from that one concert in Birmingham, including Neil's first drum solo to be allocated its own track: The Rhythm Method, a clattering tour of his musical influences.

I dropped what I thought was an insightful bomb to kick-start the interview. That Rush were a bunch of funk musicians stuck inside a progressive rock band.

"The 'progressive rock' genre. Yes." Peart curled his fingers in quotation marks, clearly irritated. I let out an involuntary bit of wee and lit another cigarette as the other lay smouldering in the ashtray.

"A lot of the early bands I was in played R&B music. At that particular time, around Toronto in general, 'blue-eyed soul' was the most popular music, so all these white bands were playing the music of James Brown and Wilson Pickett. Do you want a cigarette? Oh, you've got two already."

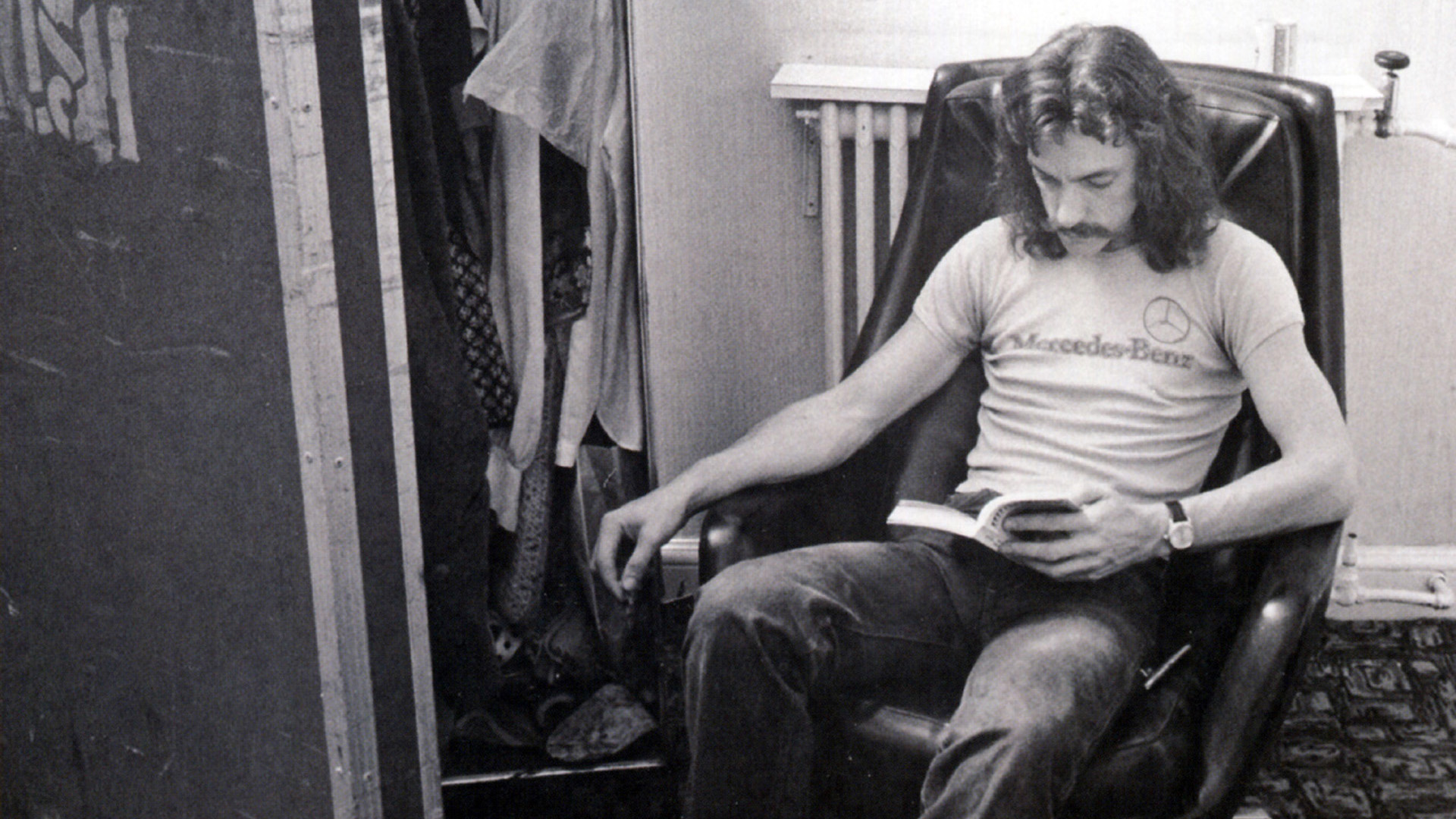

We talked about other influences. His musical journey may have started in funk bands, but the young Peart made a beeline for Britain in 1970 in search of something more. I asked him why he didn't stay.

A long pause. Draw. "It was humbling. Because I had the common syndrome, 'big fish in a small pond'.

I was living in a small city, I was in the prominent band, was the prominent drummer, and I don't think I was egotistical as such but I had an over-inflated sense of how good I was, in a naive way. Coming here and doing the audition circuit, especially at that time at the turn of the 70s when 'progressive' music was starting to become respectable... I went home tremendously humbled, obviously. I thought: 'I'm nothing and nobody and I'll never get anywhere.' My time in London was much more important to me as a person, a character, to be thrown out into the world for the first time to learn the harsh realities."

While in the UK, Peart got more into King Crimson and Michael Giles. "It was the turning point, because prior to that, I'd only been attracted to the excited, emotional side of playing, like Keith Moon. He was like the Jackson Pollock of drumming, where you'd just throw the paint at the canvas! That undisciplined style was the only kind of music that excited me up to that point. Michael combined the technical discipline with an emotional, physical abandon that taught me you could go for both. You could take the jazz ethos of technique and the wild abandon of rock and make them co-exist."

Of course, Peart returned to Canada with a newfound sense of purpose, a realisation he had to practise - a lot - and the rest has become Rush history. I told him I was an outcast among Rush fans, because I loved Signals, and felt it was a turning point for the band where all their influences collided. In the awkward silence, the PR interrupted to warn of a clearly far more important impending interview as my cigarette sent a smoke stack into dead space, like some Native American warning of inbound pillagers. Peart dismissed her from the room and leaned towards me conspiratorially.

"Your intuition is very accurate, and like you say it's a minority viewpoint, because Signals strikes most people as a weak album. It was weak only in the sense that it was exploratory and a lot of times our explorations naturally have to be a little schizophrenic. Stylistically, we tried for the first time to truly juxtapose things that were seemingly unmatchable, like Digital Man, where we took ska, hard rock and electropop - and the song remains patchy. It also took us into explorations of each other as musicians and forced us into difference roles. The whole album certainly does lack cohesiveness but it didn't lack sincerity.

"Each song eventually led us to something else. Countdown - I'm not totally satisfied with what it ended up being, but it took us to a song like Manhattan Project, it taught us how to write a documentary track. We had grown out of science fiction, so we dealt with science fact. We were finally able to present a factual thing within an emotional rock framework."

As time passed, Peart grew increasingly enthusiastic and excited. He talked about how close the band had become after so long playing together - "With Geddy, there's something truly telepathic between us" - and the elemental intensity of the Rush live experience: "You can't go onstage with barriers. You have to be wide open up there and very vulnerable. I've never been comfortable with the idea of pacing yourself. It's ten-tenths from the first beat. You can only aim to be as good as the recorded performance, which of course is perfection. It's unattainable in one sense but it deserves to be chased.

"But occasionally I can 'get into the channel', and my awareness expands to the other guys, then beyond the stage to the audience, and I may catch a face in passing... your senses are so sharp, almost like a low grade fever where everything's a little bit brighter, a little bit louder and a little bit sharper.

"But then again, if the three of us are having the kind of relaxed show we had last night, we can joke with each other, we have little lines that we can mouth to each other and laugh. The audience doesn't need to know what we're laughing about but they sense it. The same as at the end of the show, when we throw all the discipline away and during the encore we gradually melt down and by the end of it it's just a lark! The audience senses the release of tension and they sense the invitation, they're invited to relax with us now, it's fun time."

Peart had got into his stride. Words tumbled out faster and faster. The ashtray piled high with butts, he punctuated each new subject with fresh smoke as discussion darted chaotically around subjects.

"I have no equanimity with mechanical and electronic things," he explained after we discussed his use of cuttingedge electronics on stage. "It's like Woody Allen said: 'He's at two with nature.' I'm at two with mechanics and electronics."

On the other hand, Peart was clearly very comfortable in his creative world, a world he discussed with almost academic fervour. We talk about his visit to the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam, about Picasso and creative simplicty. "It seems to me that someone always thinks there's an easy way. There isn't. To get to the simple, you have to go through the complex. But to get to the sublime, you must first experience the ridiculous."

The intensity of the conversation was almost unsettling. I recall suggesting that perhaps musicians took themselves too seriously, and we ended up talking about Frank Zappa and the integrity of his strange mixture of humour and music, simplicity and complexity.

"He's so admirable. He was such a good example. In the early days when we were arguing with our record company, about why we didn't need a hit single, and why we didn't need to compromise, and why we just needed to tour and 'blah blah blah', going through all that bullshit, we had very few people to quote, and very few other examples to say, 'Look, it can be done.' But when you had people like Zappa, and like Pink Floyd, we could say: 'Look, they had long, successful careers, just because of their freedom from these kinds of constraints.' But it doesn't matter, and still our own example to our own record company, it's not taught them a thing, you know..."

Peart sighed. "I grow to despair sometimes. All it took was for them to wait two years for us to get it together, and put out a few albums that would drift along until we found our voice. And that kind of investment needs to be made in any artist." He smacks his lips. "It's hard to make them see that."

The doorbell rings repeatedly, the PR having given up hovering in favour of direct action. The interview is over.

As a codicil, I had to send Peart a package of magazines shortly afterwards. With it, I enclosed a brief note explaining how kind he had been to spend so much time talking to me, and inviting him to escape the pressures of being the world's best drummer by coming and staying at our gaff, a grubby house I shared with another penniless journo and a goth. I'm not sure really what I thought he'd make of the invitation or why I invited him. Maybe I had some Danny Baker-esque dream of sitting on Hampstead Heath lacing daisies into each other's hair, discussing philosophy or paradiddles, or both. In the event, I had a nice postcard from Neil politely saying I'd done a nice job of the interview. Hey, so Neil Peart never crashed at my house, but it was the next best thing.

Force Ten

By Gary Mackenzie

Few live rock shows saw open displays of air drumming quite like a Rush concert. And the reason was the high regard in which Rush drummer Neil Peart was held by the band's legions of fans. Almost as soon as he joined the group, Peart made an impact. The colourful, lyrical impact of 1975's Fly By Night matched the awe in which fans delighted in his drumming prowess. It was an awe and admiration that would last for the ensuing 46 years, and which still shows no signs of abating. I mean, we all know what to do at two minutes and 35 seconds into Tom Sawyer, right?

By-Tor And The Snow Dog, Fly By Night (1975)

Alongside album opener Anthem, By-tor And The Snow Dog announced Neil Peart's arrival in the most audacious and adventurous manner possible - he's all over the first four minutes of this tune, throwing out bewildering fill after bewildering fill as if his life depended on it, and matching guitar and bass unison figures note for note. His playing often feels like it's about to crash and burn while never quite doing so. It's vital, energetic work from a clearly gifted young player who has unwittingly just set himself and his new bandmates on the path to becoming rock legends.

Xanadu, A Farewell To Kings (1977)

Deliberate efforts to extend the band's musical horizons and sound palette on A Farewell To Kings gave licence to Peart to break out an assortment of traps, toys and instruments. Xanadu sees him utilising tubular bells, temple blocks, wind chimes, glockenspiel and cowbells, alongside his already expansive drumkit in a gloriously epic interpretation of Coleridge's poem Kubla Khan. He navigates the sections in 7/8 with confidence and dynamism, throwing in some truly inventive and punchy fills, and yet maintains a studied sensitivity to everything else going on around him. A landmark performance for both the band and Peart.

La Villa Strangiato, Hemispheres (1978)

Where to start with this nine-minute opus? How about the beguiling intro that just grows and grows? Or perhaps the sublime journey in 7/8 through the A Lerxst In Wonderland section with Peart building intensity from a rhythmic whisper to a dizzying percussive roar? Maybe the referencing of Raymond Scott's 1937 tune Powerhouse, (used in innumerable Warner Bros cartoons)? What about those little jazz breakdowns? The stupendous fills? The turning on-a-dime shifts in feel between different sections? The quirkiness and clear embrace of its own absurdity? This is a drum part so demanding that even Peart gave up trying to record the whole thing in one go!

Jacob's Ladder, Permanent Waves (1980)

Other tracks on Permanent Waves undoubtedly deserve attention: The Spirit Of Radio, obviously, but Freewill and Natural Science also contain some terrific stuff. Prog has chosen Jacob's Ladder for its slightly darker, quasi-classical elements, and because it's metrically quite tortuous. Sections in alternating 5/4 and 6/4 time, then the same time signatures but played by Peart and Lifeson over Lee's 4/4 vocal/keys part, a bit of 4/4 then alternating 6/8 and 7/8 bars, a few bars of 3/4 and even a solitary bar of 13/8 near the end make this an exercise in concentration. Add in a bit of timpani and tubular bells for a clever and rather classy drum part.

Tom Sawyer, Moving Pictures (1981)

We could have picked numerous tracks from Moving Pictures, such is the sheer quality and range of superlative drumming, but we've settled for just two. Tom Sawyer is a swaggering, gut-punch of a tune, propelled masterfully by Peart as he builds craftily through the verses before hitting you with big main themes. When Lee and Lifeson hit the sections in 7/8 an inspired Peart shifts into playing what are essentially two bars of 7/16 to every one bar of theirs. And then there are those awesome drum fills - bombastic, thunderous and quite brilliant. Was 'air-drumming' a thing before Tom Sawyer?

YYZ, Moving Pictures (1981)

Taking the rhythm for its opening 5/4 theme from the Morse code for Toronto Pearson International's three-letter airport location identifier, Grammy-nominated instrumental YYZ packs some serious heft, dumbfounding stop/start action, intricate interplay between the band and marvellous trading bass and drum solo moments. Delivering more in just over four minutes than many bands manage on entire albums, Peart is absolutely in the driving seat here.

Territories, Power Windows (1985)

No chaotic flurries around the kit or brain-melting odd-time signatures or furious, up-tempo pummelling. So what is Territories doing here? This is Peart building a part which, while hardly flamboyant, is quite involved and far from easy to play with any consistency. It avoids the standard rock hi-hat/snare/bass drum approach, opting instead for a handful of repeated patterns utilising toms, snare, cowbells and a smattering of electronics. Peart plays for the song, explores possibilities and refuses to churn out what many might have expected of him. It's a terrific drum part and those 80s synth hits are undeniably magnificent.

Dreamline, Roll The Bones (1991)

This is an example of Peart picking up the prevailing band ethos going into the 90s of being more direct and playing lean and mean. There are some terrific fills during this song, especially towards the end, but the drum part's main purpose is to provide focus and motion. His playing suggests an underlying frantic urge to move onward, to boldly go, to not get stuck, to exist in the now and to leave baggage behind. Being the rhythmic engine here, he captures the sense both of the song lyric and the themes of the Roll The Bones album as a whole perfectly.

O Baterista, Rush In Rio (2003)

It's simply unthinkable that any celebration of Peart's playing could ignore his semi-legendary drum solos. Prog has chosen this version, recorded right at the end of the Vapor Trails tour in 2002. Peart delves into every nook of his vast acoustic and electronic set-up, (including the obligatory cowbells), plays curious little ditties on marimba-synth, improvises against a repeated foot pattern in 3/4, cleverly throws in snippets of past solos and rounds it all off with a joyous play-along section to Count Basie's One O'clock Jump as recorded by the Buddy Rich Band. Decades of his personal drumming evolution distilled into nine minutes and greeted with true love from one of the largest audiences the band ever played to.

The Garden, Clockwork Angels (2012)

The closing track from Rush's final studio album places under the spotlight a largely overlooked aspect of Peart's playing. While much of Clockwork Angels harks back to earlier, rockier, guitar-weighted compositions and boasts possibly the heaviest drum sound ever featured on a Rush album, The Garden demonstrates Peart's musical intelligence. No drums at all for the first couple of minutes and when they enter they're not particularly outlandish. The craft here is knowing when and how to support the song, and the gradual build in intensity from the guitar solo through to the tune's denouement is masterful. The fact that the rather beautiful lyric resonates so deeply now is just an added reason to give it a listen.

The Enigma of Neil Peart

By Martin Kielty, additional research by Malcolm Dome

Neil Peart's death was announced online, the response from fans and musicians alike was phenomenal. Here was a hugely talented artist who was defined by the art he created. Prog looks at some of the emotional tributes to The Professor from the world of prog and beyond.

The fact that Neil Peart's death came as such a shock to so many people, even though he'd been severely ill for some time, is perhaps the best tribute shown to him. He commanded such respect that, despite such a tragic situation, no one wanted to breach the privacy that had always been so important to him.

Even Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson said very little in their only official statement, noting that: "our friend, soul brother and band mate of over 45 years, Neil, has lost his incredibly brave three-and-a-half year battle with brain cancer (glioblastoma)."

Peart's creative output deserved respect, of course, and will continue to do so, but the reason why the "Professor" commanded so much personal appreciation was hinted at among the hundreds of tributes paid to him in the days after his passing.

In a blog post entitled This Wasn't Supposed To Happen, DJ Donna Halper, who helped secure Rush's first US record deal, remembered Peart as a man who'd been clear about who he was from the moment they met in 1974. "Naturally, because Neil was the 'new guy,' he wanted to meet me - not because I was in any way influential, but because I already had established a relationship with Alex and Geddy, and he wanted to know more about me. He came to my apartment and we talked for several hours.

As it turned out, we had a love of literature in common - in fact, I lent him my copy of Shakespeare's King Lear, which had special meaning for both of us."

Halper, now a professor herself, said she knew from early on that Peart would always keep himself to himself. "Neil was always a very private person, and I did not expect that we would keep in touch with any regularity. In fact, as time passed, we only saw each other now and then, usually when I went backstage at a Rush concert. And because he never liked doing the endless meet and greet events where bandmembers shook hands with fans, I ended up seeing Geddy and Alex much more than I did Neil. But whenever I saw them, I always made sure they sent Neil my love."

Family was important to him - both before and after the tragic events of 1997, when he lost both his daughter and wife within 10 months of each other, leading him to consider giving up music altogether. Halper recalled him telling her that the message he'd learned from reading King Lear was: "It's not enough to say you love someone; you have to show it." He said he'd regretted not being there for his daughter Selena because of Rush's touring commitments; and when he'd married again and new daughter Olivia was born, he'd determined to be there for her.

"It was a promise he kept," Halper wrote. "I was not surprised when Neil decided to retire. I knew he had tendonitis. I knew he was in more pain than he let on. And while fans were, of course, disappointed, being a 'retired drummer' gave him the chance to spend more time with his wife and daughter. I kept in contact with him through his closest friend Craig, and I was so glad to hear he was content and enjoying his life."

Friends were also important to him, even if he was cautious about how many he kept close. Fellow drummer Mike Portnoy recalled Peart as a "gracious host" whenever they met, saying he was "always inviting me to come to soundcheck and spend some time before the show whenever Rush was passing through. Always sending complimentary copies of his new books, or holiday emails with pictures of he and his young daughter Olivia."

Portnoy continued: "I have so many memories through the years, but probably the most special was the last time I saw him. I took my son Max to see Rush on their farewell tour." Peart had "let Max play his drums, gave him a pair of sticks and an autographed snare drum head and opened up his dressing room to us for the evening. The point is, if you were his guest you were family."

He added: "Neil Peart will always be a mentor and a hero to me and his influence on me as a drummer for the past 40 years is absolutely impossible to measure."

Todd Sucherman of Styx recalled a similar warm welcome, even though he only met Peart once, when they were both recording in the same studio complex in 2009. "We shook hands and chatted, I congratulated him on his new young daughter, and as I remember, he was the one that was asking me all the questions. He wanted to know about working with Brian Wilson. We brought up many mutual friends." Sucherman added: "He was incredibly warm, personable, curious, and felt we could have kept the conversation going had it not been for 30 people waiting to get to work."

Carl Palmer reported a similar experience, saying he'd only met Peart once but found him to be "a great drummer and a gentleman." He noted: "He will be remembered as being one of the most innovative drummers in the prog world. He made it a better place for all of us."

Primus leader Les Claypool revealed another side of a man he described as "a pensive, sharp-witted intellect whom I looked up to and admired greatly," recounting the pleasure of having "played with him, laughed with him and rode with him at excessive speeds in one of his many exotic vehicles." Peart shared his passion for motorcycling alone for thousands of miles, during Rush tours and beyond them, in his books and blogs. He'd travelled 55,000 miles in the aftermath of losing his first family, in the process of rediscovering himself.

Claypool described Peart as a "genius," adding: "As a musician he was unparalleled, blasting open huge doors into the realms of new percussive stratospheres. As a lyricist, he was like the Ray Bradbury of rock penning rhymes that evoke imagery both cerebral and tactile."

While the vast majority of the people whose lives he touched never had the opportunity to see such personality traits for themselves, they were still affected by them through his work. That sense of being a voyager and observer (he liked the idea of being a "ghost rider") contributed to the ideas he expressed through Rush's percussion and lyrics. Longtime producer Terry Brown said: "I have so many fond memories of good times spent listening to him compose some of the greatest percussive moments on record and working with his lyrics, which he took so much care to write for us all to cherish."

Yes paid tribute by saying: "Neil Peart was one of the most innovative and exciting drummers and lyricists in the history of music." They described him as "an inspiration to millions and a true gentleman."

Lonely Robot, Frost* and Kino musician John Mitchell noted: "I know how much Rush mean to a lot of people, and to a lot of people my age, this dude contributed to the soundtrack of their youth."

Ray Alder of Fates Warning said: "He was in my opinion the best drummer in the world and he changed the way people thought about drumming with every incredible album he made. Also, he created the world's greatest air drummers." Dan Briggs of Between The Buried And Me argued that Peart had "pushed boundaries and made myself and music in general better because of it."

Fellow Canadians The Tea Party said Peart had "played such a pivotal role in all we were, are, and will become" and Gong vocalist Kavus Tobari said he'd "cemented my love of drums and drummers." The Flaming Lips' Steven Drozd offered gratitude for how he'd "created a whole new world for a lot of us." Sons Of Apollo's Billy Sheehan wrote: "What a brilliant and wonderful man. He left his mark on the world, music, drumming and so much more." Dream Theater's tribute read: "We are deeply saddened to hear of the loss of one of the world's greatest artists, lyricists and drummers of all time. To say that Neil and the music he was a part of was an influence on Dream Theater is a gross understatement."

Echolyn's Brett Kull recalled the moment, when in 1979, he first heard Rush's Hemispheres. "I felt as if I was being initiated into some sort of sci-fi, intellectual, secret sect," he said. "I'll never forget that day. It was the beginning of a soundtrack that forged my teenage exuberance. I always think of the countless hours playing along to Neil Peart's drumming in my bedroom; learning those changes and trying to be tight with the band. I also loved that Neil brought a certain amount of literature savviness to the band. I liked that he wrote about different situations and concepts than the normal humdrum you hear in most songs. He was fearless."

Tributes also came from names as varied as Marillion, Jeff Scott Soto, Umphrey's McGee, Steve Hackett and many others. Even Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau spoke up, saying: "We've lost a legend. But his influence and legacy will live on forever in the hearts of music lovers in Canada and around the world."

And while Peart would almost certainly have shied away from the number of artists expressing gratitude for his influence, he might also have repeated one of his guiding philosophies: "What is a master but a master student?"

Former DJ Halper discussed Peart's generosity in terms of financial aid, separately from spirit, noting that: "when he gave (which he often did), he never wanted to call attention to himself." In their brief statement Rush suggested that fans might want to show the same kindness, asking them to "choose a cancer research group or charity of their choice and make a donation in Neil Peart's name."

"Neil was an honourable, ethical human being," Halper continued. "Despite being one of the music industry's greatest drummers, he was never arrogant. He treated drumming and songwriting, as artforms, and he elevated both. He loved being a musician, and his lyrics resonated with so many fans. He lived his life his way, never afraid to be himself, encouraging others to be themselves too. He left a large body of incredible music, that will live on. And he left years of wonderful memories that his millions of fans will never forget. To think of a world without Neil in it breaks my heart. But I consider myself fortunate to have known him. May he rest in peace."

While most of us would have loved to know as much of the artist as we did of the art, everything Peart wanted us to know about him was delivered in a painstaking, measured manner. In many ways he was the art he created.