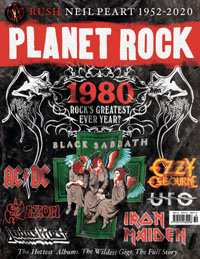

Exit the Warrior: Neil Peart - A Tribute

On January 7th, Rush's drummer lost his fight with brain cancer. James McNair pays tribute to a true rock original.

By James McNair, Planet Rock Issue #19, April 2020, transcribed by John Patuto

"Suddenly, you were gone, From all of the lives you left your mark upon."

I HAVE A THEORY as to why Neil Peart was the best guy to air-drum to. Nobody played around a kit like Neil. As teenage Rush fans high on nothing more than the band's music, it took you and your mate at least 180-degrees of space to mime that bit from Tom Sawyer.

In the UK, the sad news broke late on the evening of Friday, January 10. Rush drummer and lyricist Neil Peart was dead at 67. He had died of brain cancer in Santa Monica, California on January 7, The Guardian reported. I stumbled across the story on my phone just before going to sleep. That couldn't be true, could it?

By next morning the story had grown truer and bigger. From Dave Grohl to Bill Ward, ace drummers the world over were on social media putting touching words to the sad little flam Neil's passing had played on their hearts. Meanwhile, I'd been moping around the house with my partner and our seven-year old, though what I really needed was someone au fait with YYZ or maybe even Didacts And Narpets, Peart's magnificent showcase section from Caress Of Steel's The Fountain Of Lamneth. "Neil Peart has died!" I thought internally "NEIL FUCKING PEART!" But I kept schtum and buttered the toast, and thankfully the jungle drums of my own little network of Rush fans soon began to pound.

"Devastating news," texted my mate Paul.

"Awful," I texted back. "Seems ridiculous, perhaps, but I feel the loss."

"Why ridiculous?" he replied.

"We grew up with their music. For 40 years Rush were part of my mental landscape."

"Bonham, Moon, Baker and now Peart," texted another pal, Donald. "There can't be any really great drummers left."

"Animal from The Muppets," I texted back, a poor attempt at levity. I was still in denial. I hadn't listened to anything by Rush that morning, and I wouldn't listen to anything by Rush for quite a few days.

Donald contacted me again later. "Here's the best fan comment I've read so far," he wrote: "'I can't help thinking he's chuckling somewhere knowing there's hundreds of bands with gigs tonight trying to figure out an 'easy' Rush song.'" That was quite good. Clearly others were in denial too.

Later still, I was thinking about another joke I'd made. Interviewing Alex Lifeson for a cover story in this magazine last year, broaching the fact that Neil's young daughter Olivia had reportedly been learning drums from him, I jested that perhaps all Alex and Geddy had to do was wait 10 years or so and then they could reform Rush with Olivia replacing Neil.

The gag had landed a little bumpily and I wasn't sure why, since, in my experience, Alex was usually happy to indulge such tosh. Everything is clearer with hindsight. I'd inadvertently reminded him of Neil's brain cancer diagnosis, something he and Geddy had already been keeping secret for two years. No wonder the poor guy was thrown.

"You can do a lot in a lifetime/ If you don't burn out too fast."

Even aged 22, Neil Peart was a drumming colossus. Scrolling down through the Rush Is A Band Twitter feed that currently leaves me teary-eyed, down past news of a possible Neil tribute statue in Lakeside Park, Ontario, down past a photo of the handwritten letter Neil sent to 16-year-old Rush fan Patrick Jones, brother of Manic Street Preachers' bassist Nicky Wire, in 1981; down past heartfelt tributes from Bryan Adams, Carl Palmer and David Coverdale, I keep playing a video clip someone has posted of Rush performing Anthem in the mid-'70s. Neil's deft power is already astonishing, and he's rocking the one-handed stick twirls he likely learned watching one of his heroes, Keith Moon. Even circa Rush's 1975 album Fly By Night Neil already had enough skill and finesse to rest on his laurels - but he never would.

Rush were the kind of band you could actually grow up with, or maybe, in fact, to. They were not the developmentally-stunted individuals of hard rock cliche, or at least not for long. It was Neil, moreover, the geeky, painfully shy guy whom Alex and Geddy dubbed The Professor, leading the charge of the enlightened brigade. When not pictured dwarfed by the latest incarnation of his everything-and-the-kitchen-sink drum kit he was generally photographed smoking and reading. You wonder, really, how many of Neil Peart's lyrics made it into teenage Rush fans' English essay assignments, his insights and philosophical musings passed off as our own original thought. It wasn't until I was in my mid-twenties, I began to realise just how acute Neil's lyrics were. Like many Rush fans, I'd grown used to mapping out stages of my life alongside the band's successive album releases; hence, even when on holiday in Italy in 1991, I tracked down a cassette copy of Roll The Bones in Florence the day it was released there.

It was the second track Bravado, a song also commendable for Neil's fabulous, economical drumming, which seemed to bring a new level of insight to his lyrics. "If we keep our pride/Though paradise is lost/We will pay the price/But we will not count the cost," sings Geddy Lee. How many drummers does it take to give Shakespeare a run for his money? Precisely, one.

"Pack up all those phantoms/Shoulder that invisible load/Keep on riding north and west/That wilderness road/ Like a ghost rider"

Only one thing was going to derail Neil Peart's ever upward trajectory: personal tragedy. In August 1997, his then only child, 19-year old daughter, Selena, was killed in a car crash. When Peart's wife Jacqueline died of cancer just 10 months later, Neil attributed her passing to a "broken heart" as well as the disease. "It was a slow suicide by apathy," he recalled. "She just didn't care."

Peart told his bandmates to consider him retired, and began trying to process his grief. He mostly did so alone, travelling some 55,000 miles across North and Central America by motorcycle, as documented in his touching 2002 travel memoir Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road.

"Certainly the first couple of chapters were very difficult to read," Alex Lifeson told me when I interviewed him and Geddy Lee in Toronto in 2003. "The book was a reminder of just how dark those days were for Neil."

"I'd get these postcards from him," added Lee. "That was his way of letting me know, 'I'm here, still. I'm out here fucked-up and moving around.' We had this network of people checking up on him behind the scenes."

It had seemed that Rush was over, but when Peart met Carrie Nuttall and married her in September 2000, new love proved to be the catalyst for his eventual return to the band. After years of not playing drums, it took great courage and an Olympian effort of will for Neil to reach peak virtuosity again for 2002's Vapor Trails.

"Frankly, I don't know how he did it", Lee told me. "It's in his nature to be solitary and it would have been much easier for him to run off and hide, but he didn't."

"Freeze this moment a little bit longer/Make each sensation a little bit stronger..."

Were there any jokes in Rush's lyrics? Not really. Not unless you count I Think I'm Going Bald, written back around 1975 when all three members of Rush were nothing if not hirsute. Yet this was a trio that really liked to laugh, and a band that shared a surreal sense of humour. Witness Lifeson's infamous "blah, blah, blah" speech during the band's induction into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2013, and their oompah-band version of Spirit Of Radio. Most of all, though, witness the drunken band dinner that Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn filmed for their acclaimed 2010 Rush documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage.

"I don't make plans for the next five years; I don't even buy green bananas," jokes Peart, as they dine at a posh hunting lodge. He's mostly an audience for Lee and Lifeson's banter, but freed by alcohol and four decades of deeply treasured friendship, he's soon crying with laughter. "You're strong as an ox," Lee says of Lifeson. "Yes, but I look like one too," replies the guitarist. It's heartbreaking to watch that footage and know that Rush's remarkable three-way bond has now been severed forever.

When Peart came back to Rush after the loss of his first wife and daughter, it was because of that bond. "He said that he owed it to the concept of the band not to let it end like that," Lee told me in 2003. "He felt it should only finish out of choice, and I thought that was quite a statement."

Despite Peart's great physical pain and pressing health concerns, that was exactly how it did end. When Rush played the final date of their final tour at the Los Angeles Forum on August 1, 2015, they walked off stage with heads held high, a still-magnificent trio who knew they should quit before the diminishing powers Neil sketched in 1982 Rush masterpiece Losing It became their own reality. There's another short section in Beyond The Lighted Stage, where Lee and Lifeson are pictured with fans at various backstage meet and greets. One of them was at the SECC Arena in Glasgow in 2007, and for a split second there I am; me and my old pals Ian and David flanked by a smiling Geddy and Alex. Neil didn't do meet-and-greets, of course, and I never got to interview him, but it's a nice thought for me that, having seen the film, Neil Peart, the undisputed master of parsing time with sticks, might briefly have noticed my existence.

That he will be greatly missed both as a human being and a superhuman drummer speaks volumes, but as The Garden, a song from Rush's final album Clockwork Angels reminds us, Neil had already thought all that stuff through.

"The measure of a life is a measure of love and respect," he wrote. "So hard to earn so easily burned."

Job done, Mr Peart. You won our love and respect and you aced it. So long and thanks for all the fills.