The Presto Tourbook

Scissors, Paper, Stone

by Neil Peart

Writing a story about making a record is like making a record; you never get it quite right, so you keep trying. In the past I've talked about the studios, the people we've worked with, the weather, our methods of work -- lots about what we do, but nothing about why we do it, and nothing about how the songs themselves develop. So maybe it's time to try a glass-bottom boat on those murky waters.

One of those French guys, Balzac or Flaubert, said that a novel should be applies to songwriting as well. "Reflecting on life" could certainly be the unifying theme of Rush's odyssey through the years -- though of course we never thought of it at the time. We were too busy moving down the road, as most people are. But at least when you're moving fast, you have to look ahead; there's only time for a quick glance in the rear-view, just to make sure no flashing red lights are gaining. Otherwise it's no good dwelling on what's behind you. Just your own tailights.

To belabor the metaphor in a general sense: all of us are moving down that road with different mirrors, and we don't just reflect life, we respond to it. We filter things through our own lenses, and respond according to our temperaments and moods. As the Zen farmer says: "That's why they make different-colored neckties."

That's why they make different-sounding music too. To beat another metaphor into submission: in musical terms Rush is not so much a mirror, but a satellite dish moving down the road, soaking up different styles, methods, and designs. When the time comes to work on new songs, you turn on the satellite descrambler, unfilter your lenses, activate the manure detector, check the rear-view mirror, and try desperately to unmix your metaphors.

When the three of us start working on a new record, we have NO idea what we'll come up with. There is only the desire to do it, and the confidence that we can. The uneasiness of starting from nothing is dissipated by the first song or two, but still the mystery remains -- in the truest sense, we don't know what we're doing. We know it seems right; we know that it's what we want to do at that point in time, but we don't know what it adds up to. And often we won't know for a long time -- until well after the record has been released and everyone else has had their say about it. Then it seems to crystallize in our own minds, and we develop of little objectivity about it -- what we're pleased with, and where it could have been better.

And that's where progression comes in -- where it could have been better. As a band and as individuals, we always have a hidden agenda, a subtext of motivation which is based on dissatisfaction with past work, and desire to improve. That agenda has changed as we have changed; when we started out, we just wanted to learn how to play, and sometimes our songs were just vehicles for technical experiments and the Joy of Indulgence. But still, playing is the foundation for us -- the Stone -- and rock is our favorite kind of stone. Despite our dabbles in other styles, it is the energy, flexibility, and attitude of rock which remain most compelling for us. We exercised our fingers and exorcized our demons by trying every note we could reach, in every time signature we could count on our fingers. But after we'd played with those toys for awhile, the songs themselves began to attract our interest. Rock is not made of Stone alone, and we wanted to learn more about conveying what we felt as powerfully as we could. Paper wraps Stone -- the song contains they playing, gives it structure and meaning.

More experiments resulted as we pursued that goal, and those experiments had to lead us into the field of arrangement. Once we felt more satisfied with the pieces of the songs, and how we played them as individuals and as a band, it became more important how we assembled the pieces. Scissors cut Paper -- the arrangement shapes the songs, gives it focus and balance. So our last few albums have relected that interest, tinkering with melodic and rhythmic structure in pursuit of the best possible interpretation of the song.

All of these qualities -- arrangement, composition, and musicianship -- add up to one thing: presentation. Beyond the idea, presentation is everything, and must take that spark of possibility, the idea, from inner-ear potential to a realized work. In an ideal song, music conveys the feeling and lyrics the thought. Some overlap is desirable -- you want ideas in the music and emotion in the lyrics -- but the voice often carries that burden, the job of wedding the thoughts and feelings. Since the goal of those thoughts and feelings is to reach the listener, and hopefully be responded to, success depends on the best possible balance of structure, song, and skill. Scissors, paper, stone. Where once we concentrated on each of them more-or-less exclusively, now we like to think that each element has been stored in the "tool box," and we're trying to learn how to juggle them all at once (though juggling scissors can be damned unpleasant).

At the same time, Rush's hidden agenda has a wide scope. The presentation of our music has to accomplish several demands: it has to be all the above, plus it must be intersting, and challenging to play, and remain satisfying in the long term -- when we play it night after night on the road. The recording must be captured as well as men and machines possibly can, and thus be satisfying to listen to, as well as fit to stand as the "benchmark" performance, the one we'll try to recrate on each of those stages.

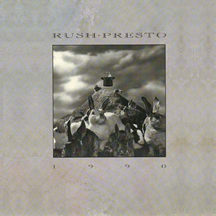

Before making Presto we had left those stages behind for a while. At the end of the Hold Your Fire tour we put together the live album and video, A Show Of Glands -- I mean Hands. Because we were just about to sign with a different record company, Atlantic, we found ourselves free of deadlines and obligations -- for the first time in fifteen years -- so we decided to make the most of that. We took some time off, got to know ourselves and our families once again, and generally just backed away from the infectious machinery of Rash -- I mean Rush.

This was a good and important thing, although it was one of the few times in our history when the future was in doubt -- none of us really knew what would happen next. After that six-month hiatus, when Geddy and Alex came over to my house to discuss our future, there was no sense of compulsion about it -- it was simply a question of what we wanted to do. And, we decided, what we wanted to do was make another record. The reasons remain elusive, but the motivation seems obvious: something to do with another chance to express ourselves, to try to communicate what interests us in words and music, and, simplest of all, a chance to play. In both senses. Without any obligations on us, we found we were still excited about making music together, and truly wanted to make something new.

For Presto, like all of our records in recent years, we started with a trip to the country. We rented a house with a small studio at one end, a desk at the other, and all the usual stuff in the middle. During the bright winter afternoons, Geddy and Alex worked in the studio, developing musical ideas on a portable recording setup, while I sat at my desk in the other end, staring out at the snow-covered trees and rewriting lyrics. At the end of the day I might wander into the studio, ice cubes clinking, and listen to what they'd been up to, and if I'd been lucky, show them something new. It was the perfect situation; isolated, yet near enough Toronto that we could commute home for the weekends, and with the studio and house connected, whenever we had ideas to share we could run from end to end with tapes and bits of paper.

Personally, this is my favorite part of everything we do: just the three of us and a couple of guys to keep the equipment running. We have nothing else to worry about but writing new songs, and making them as good as we can. With few distractions, we can concentrate on the work, and also feel the reward: the excitement of creating things, of responding to each other's ideas, and the instant gratification of putting brand-new songs down on tape. At this time we get the real feedback from our work; it's new enough to be as exciting for us as we hope it will be for the listener.

And that is where a coproducer comes into the picture. Peter Collins, who worked with us on Power Windows and Hold Your Fire, told us that he felt his own career needed more variety and scope, and reluctantly bowed out of our next album. By this time we had learned how to make a record ourselves if we wanted to, but we still wanted an Objective Ear, someone whose judgment and ideas we could trust. Once we'd sorted out the paper and stone, we wanted someone to help with the scissors.

Of a few different candidates, Rupert Hine was the one we decided on. Rupert is a songwriter, singer, and keyboard player in his own right, and has made about fifteen albums himself, in addition to producing seventy-odd records, for other people, like Tina Turner, Howard Jones, and The Fixx. All this experience, combined with his ideas and enthusiasm, made Rupert's input valuable, particularly in the area of keyboard and vocal arrangements. We were a little bemused when we first played the songs for him, and at the end of some of them he actually seemed to be laughing! We looked at each other, eyebrows raised as if to say: "He thinks our songs are funny?" But evidently it was a laugh of pleasure; he stayed 'til the end.

For the past eight years Rupert and engineer Stephen Tayler have worked together as a production team, and at Rupert's urging, we brought Stephen in to work behind the console. As an engineer Stephen was fast, decisive, enthusiastic, and always able to evoke the desired sound, while his unfailing good humore, like Rupert's, contributed to making Presto the most relaxed sessions we've enjoyed in years. But it was as a volleyball player that Stephen really shone, unanimously voted "rookie of the year" in our midnight games at Le Studio.

A long day's work behind us, we gathered outside, charged by the cool air of early summer in the Laurentians. We doused ourselves with bug repellant, then gathered on the floodlit grass, took our sides, and performed a kind of St. Vitus Dance to shake off the mosquitoes. Occasionally one of us hit the ball in the right direction -- but not often. Mostly it was punched madly toward the lake, or missed completely, to trickle away into the dark and scary woods. ("That's okay; I'll get it.") We were as amused by Rupert's efforts at volleyball as he'd been by our songs, but indeed, all of us had our moments -- laughter contributed more to the game than skill. And if the double-distilled French refreshments subtracted from our skill, they added to our laughter.

Between games the shout went up: "Drink!", and obediently we ran to the line of brandy glasses on the porch. Richard the Raccoon poked his masked face out from beneath the stairs, wanting to know what all the noise was about. "Richard!" we shouted, and the poor frightened beastie ran back under the steps, and we ran laughing back onto the court. The floodlights silvered the grass, an island of light set apart from the world, like a stage.

On this stage, however, we leave out the drive for excellence; no pressure from within, no expectations from others. Mistakes are not a curse, but cause for laughter, and on this stage, the play's the thing -- we can forget that we also have to work together.

Work together, play together, frighten small mammals together: Are we having fun yet? Yes, we are. And that, now that I think about it, is why we do what we do, and why we keep doing it: We have fun together. How boring it would be if we didn't. Not only that, but we work well together too, balancing each other like a three-sided mirror, each reflecting a different view, but all moving down the road together. As the Zen farmer says: "Life is like the scissors-paper-stone game: None of the answers is always right, but each one sometimes is."

Alex Lifeson

After taking a long break from touring, I started thinking about setting up a new system that was different from what I had been using during the last few tours. It occurred to me that perhaps I should consider using equipment manufactured in a country on the leading edge of this technology, and in the spirit of perestroika and glasnost decided that the Soviet Union was just the place. I arrived in Moscow and made my way to the local music shop: "Large Fun Music Store," and spoke to the sales comrade about the latest in musical equipment.

"First ting, you are coming to right place. Second ting, I give you best deal dis side of Leningrad and I want you to know I'm losing rubles on dis deal. Nobody can ever say Yuri Leestiniki try to rip dem up."

Feeling assured that I wasn't getting rubble for my ruble, I asked Yuri to show me what he had in the way of guitars. He returned ten minutes later with the strangest guitar case I'd ever seen. It was quite flat and about a half meter square, made of plywood with a long nail hammered into the top and bent over to use for a carrying handle.

"Dis is last model in whole Soviet Union and was sold to guy from Kiev but he never call me back today, so even because I will to get in trouble, I will sell to you."

What a deal, I thought.

"Okay Yuri," I said, "let's have a look at it."

Yuri opened the case by prying with two screw drivers at either end and keeping his foot firmly on the 'carrying nail.' When he finally got it opened, there was this...this thing. It sort of looked like the shape of a guitar but in place of the pickups were these magnets like we used to have in school with the red-painted ends, and in place of a volume control was an on/off switch that looked as if it had come out of a household fuse panel.

Oh yeah, it didn't have a neck.

"Oh, you are wanting neck too?" he said, surprised. "Neck is extra but I can order for you one to be here in four to six month. Maybe."

"Okay," I said, "forget the guitar for now. What about amplifiers?"

"Best amplifier in world I have in stock right now. Is called a "Khrumy" and it come already wit speaker. Is new modren design and also is good for heavy-metal sound because is made from pure and complete iron. You are first to solder wires into electric plug on wall in house and after to maybe stand back for maybe one minutes. Is good to wear big orange rubber gloves when making amplifier to work. Is good amp but sometimes someting is maybe breaking, and so is good buying one more amplifier for spare part. Is nice green color, don't you tink?"

Yes, well. I asked about the price anyway, thinking that it could make a decent fridge at least.

"If you have to ask, you are not affording it," he answered me. "But I am liking you and we are just finish a big sale. Dis is last day as matter of fact. I must to be crazy but I let it go for...aah...eight tousand rubles."

"What!?" I screamed.

"Okay, okay. How about two pair of jeans and maybe some sandwich."

The amp came with wheels and a small thirty-horsepower motor, so after I paid Yuri and we got the motor started, I said goodbye and he reminded me to fill in the warranty card for the ten-day warranty. I drove the amp back to the airport and headed home.

I arrived home and was excited to get the amp plugged in and hear it. I got out the soldering gun, soldered the wires into the receptacle, stood back for one minute...and my house burned down.

You know, I kinda liked my old gear.

Geddy Lee

Thurs. Jan 18th -- 10:25 a.m.

Subject: A Kwipment Lisp

Yes, I've just received a fax (what a modrin world) from my Pal Pratt (pardon my French) requesting this year's equipment list. Sounds exciting, doesn't it? An equipment list. Just rolls off the tongue. Oh boy! Equipment. You mean equipment for performance? Equipment for living on the road? Well, how about things I need. Or things I love. Nope! Too small a space. A list or is it liszt or at least, er, excuse me -- I guess I'm wanted back on the planet Earth. Does it sound like I'm stalling? Or trying to shirk my responsibilities? It does? I apologize. Where were we? Lists. Ah yes, what I use. Well, I use a Wal and a Leica R5, some big amps and a Wilson Profile (what a profile!). Some black jeans and shoes. (It's so hard to find good shoes isn't it?) I now have a Mizuno Liteflex glove and lots of Roland stuff (especially samplers!...love those samplers -- need those samplers. Once again I've been Saved By Technology).

I also use the sports section of USA Today. I need that daily! I also use Jack Secret, John Irving, W.P. Kinsella, W.C. Fields, Skip G., Pedro Almodovar, Modigliani, Andre Kertesz, Sandy Koufax, Diego Giacometti (sorry, dreaming again) and obviously Woody Allen, M. Joe, B. Mink, sweaters by Loucas (just tell me if this is going too far). Okay -- I also have some Fender Basses; that's equipment!! And one N. Young and Julian W. and some Steinbergers and Snidermans and...

Oh...have I run out of time? But there's so much more...oh well...next time...Peace and save the planet!

Neil Peart

Don't be fooled, these are not new drums. Nope, they're the same Ludwigs as last time, the ones that used to be pinkish, only now they're a dark, plummy sort of purplish color. (Beautifully done by Paintworks).

Cymbals are all by Avedis Zildjian, except for the Chinese Wuhans, and the brass-plated hardware is a hybrid of what-have-you: Ludwig, Tama, Pearl, Premier, and some custom-made bits from the Percussion JUSTIFY in Fort Wayne. The gong bass drum comes from Tama, and the cowbells come from Guernsey & Holstein. Sticks are Promark 747, and heads -- always subject to change, just like human ones -- are some combination or other of Remo and Evans. I just keep changing my mind -- and my heads.

Same with snare drums. That remains an open question, but I'm sure to using some combination of my old reliable Slingerland, a Solid Percussion piccolo, an old Camco, and/or a Ludwig 13" piccolo (cute little thing).

The electronics are triggered by d-drum pads and Shark foot pedals, driving a Yamaha midi controller and an Akai S900 sampler. A KAT midi-marimba drives another Akai for all the keyboard percussion parts and various effects.

You know, I was thinking about what my drum kit would look like if I had all the real instruments up there, rather than a box full of floppy disks and a couple of samplers. Picture a stage which contained (in addition to that little ol' drumset): temple blocks, orchestra bells, bell tree, glockenspiel, marimba, various African drums (including ones like 'djembe' that I don't even know what it looks like), three tympani, a full symphony orchestra, a 'beeper,' a big gong, harp, synthesizer, congas, bongos, another timbale, castanets, voice-drums (recorded drum sounds vocalized by MOI) a big huge sheet of metal, jackhammer, wood block, claves, jingled coins, my old red Tama drumkit, and Count Basie and his band.

Oh sure, it would look great alright, but honestly -- where would I put all that stuff? And where would the other two guys stand?

Yeah, you're right; I don't need those guys anyway.

Management by Ray Danniels, SRO, Toronto

Tour Manager and Lighting Director: Howard Ungerleider

President and Stage Manager: Liam Birt

Production Manager: Nick Kotos

Cocnert Sound Engineer: Robert Scovill

Stage Left Technician: Skip Gildersleeve

Centre Stage Technician: Larry Allen

Stage Right Technician: Jim Johnson

Keyboard Technician: Tony Geranios

Stage Monitor Engineer: Bill Chrysler

Personal Assistant: Andrew MacNaughtan

Concert Sound by Electrotec: Ted Leamy, Brad Madix, John Reding, Curtis Springer

Lighting by See Factor: Mike Weiss, Jack Funk, Greg Scott, Steve Kostecke

Varilites: Matt Druzbik, Colin Compton

Lasers by Laserlite F/X: Alan Niebur, Charlie Passarelli

Rear Screen Projections created by BearSpots: Norman Stangl, Clive Smith and John Halfpenny

Projectionist: John Coffield

Concert Rigging by IMC: Billy Collins, Mike McDonald and Stephan Herter

Carpenter (and Stage Right Assistant): George Steinert

Carpenter: Sal Marinello

Drivers: Tom Whittaker, Mac McLear, Randy McDaniel, Jerry Henderson, Tom Hartman, John Davis, Bob Hardison, Dave Cook, Ron Sagnip, Stan Whittaker

Tour Merchandise: Mike McLoughlin

Booking Agencies: International Creative Management, NYC, The Agency Group, London, The Agency, Toronto

A special thank you to Roland and Saved By Technology for their technical supererogation.

Program Design: Hugh Syme

Typesetting: California Phototypography Company, Inc.

Contributing Photographers: Fin Costello, Andrew MacNaughtan, Dimo Safari, Deborah Samuel, Scarpati, Albrecht Durer