"The Secrets Of Playing While Singing" and

"Working With a Drummer...How To Sound Your Best"

By Jeff MacKay, Canadian Musician Vol. XXI No. 5 Sep/Oct, and No.6 Nov/Dec 1999, transcribed by pwrwindows

[Transcriber's Note: 'Canadian Musician' published the following interview with Geddy Lee over two issues in 1999, presented here as one transcript. "The Secrets Of Playing While Singing" appeared in the September/October issue, while "Working With a Drummer...How To Sound Your Best" appeared in the subsequent November/December issue.]

The Secrets Of Playing While Singing

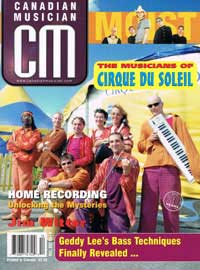

Canadian Musician Vol. XXI No. 5 Sep/Oct 1999

This issue, CM has brought you none other than Rush's bass player: Geddy Lee. We'll be doing a series of columns from an interview conducted in late summer.

Canadian Musician: First off, why did you pick bass? How'd you get into it?

Geddy Lee: I first started playing guitar when I was about 14, and the local group of guys I was hanging out with, nobody really wanted to play bass, because it meant you had to spend the money and actually purchase a bass. I was kind of nominated by everybody else: "You play bass!" So ...

Were you the worst guitar player or something?

I don't know why, but just kind of worked out. It was up to me to get it together. Maybe they thought I was the only one who could get the cash together to buy a bass or something. Anyway, I bothered my mother to get an advance - I used to work for her in her variety store on Saturdays. So I got an advance and I went to the local music store and bought a Canora bass for about $35. I started learning how to play bass, and basically learned to play any of the songs of the bands that we liked. I would just try to do what everybody does at home and listened to the parts and I mimicked them.

Did you ever take formal lessons?

Never.

Do you read music?

Very, very slowly.

Both keyboard and bass?

Yeah. I took piano lessons actually, later. In my 30s I started studying piano and that's when I started getting that end of things together, and with all the touring we were doing at that period it became very difficult to keep those lessons going. Eventually they fell by the wayside. But they were fun while they lasted.

So, when playing bass while singing, how did you get started with that, and also how did you learn?

Well, I was always a vocalist first, and when I was in school I was in the choir, and I always sang. I always had kind of a soprano voice, so it was kind of natural that I was going to be the guy who sang, and it was up to me to also play bass. You know, I started emulating people like Jack Bruce, who I greatly admired when I was younger. It was just a matter of figuring out how to do it. There were a number of times where I thought it was impossible and I could never pull it off, but for me it was always a matter of learning the bass parts first and learning them so well that I didn't have to think about them while I was singing. And then, you know, concentrating on the vocal part of things. If ever there was a conflict between what I was playing and what I was singing, I would slightly rearrange what I was playing to make it somehow easier for me to actually get the syncopation of the two together.

Do you think bass parts get simpler when bassists start singing? Do they get more rhythmic?

Sometimes, yeah, but sometimes with our music, it's not a matter of making it simpler, it's just making it a little different or making it have more connection with the rhythm of what I'm singing. Sometimes that's more important than even making it simpler. And I've found that if you really rehearse your bass parts a lot, it's easier than you think. It's kind of like any physical activity or sports activity, you know: the more you do it, the more the muscle memory kind of takes over for you and suddenly just clicks into place. I've found on almost every rehearsal that I've ever done, ever, I reach a point of total frustration where I think, "I'm not going to be able to do this." Especially when we were doing stuff from albums like Hemispheres, where the musical parts are so complex. And yet, if I just keep banging away at it, eventually you just sort it out, and the things that you have to change in the bass part are usually fairly subtle, so that the average listener wouldn't really perceive that you've maybe slightly modified the bass part.

Now you mentioned rehearsing. What's your rehearsal schedule like now? Do you still practice all the time?

No, I don't practice nearly as much as I used to.

I knew with Rush it's kind of like record, tour, time off ...

You know, for me rehearsal these days is directly correlated to the project that I'm doing at the time. So if I'm getting ready for a tour, yeah, well, I will rehearse like a maniac. And if I'm getting ready to record, we go through a period usually in recording where two months previous to recording is writing and working out the parts. After that two months period of writing, once the song arrangements are finalized, I'll spend at least a week or two rehearsing my individual parts every day just as a matter of exercise. Even if it's just 45 minutes and even if I'm travelling. I'll take a small little bass along with me and just go through the motions of playing those parts, so when it comes time to record them, I don't have to worry about writing the part as I'm recording. I can just concentrate on performance. But in the off time, like now I'm involved in various production work with different people and doing a lot of writing, so I'm very involved musically, but I'm not really involved musically as a bass player as much as maybe I should be. (laughs)

With your rehearsal and that as well, do you always sing when you rehearse? Like you do both together, or how do you handle it?

Only if I'm preparing for a tour. Otherwise I just worry about the bass part. For an album, too. I mean, I don't want to restrict what I'm playing as a bass player when I'm recording, because to me it's more important to do the part that suits the song or that suits my ambitions for the song ...

... and you'll figure it out later.

Yeah, and I'll worry about it later. (laughs)

With recording then, too, I'm just curious, I assume you play both parts separately. Have you ever done it at the same time?

Vocals and bass? No. It would just not be practical.

Too much mic bleed.

Yeah.

Playing live, since that's when you do the vocals and bass together the most, what's going through your mind?

When I'm singing, I'm really thinking about ...

Like are you looking at the crowd, or ...

No, I'm thinking about singing in tune. (laughs)

So lyrics, again, become second nature?

Absolutely. Lyrics are second nature. Sometimes I forget them, and sometimes I need to have little taped reminders for lyrics. As I age, my memory for lyrics becomes more faulty.

Well, I've actually heard that Axl Rose used to have a television prompter for his lyrics ...

Yeah, I've used that in the past from time to time too. That definitely saves your ass. (laughs)

Do you find you have to use it much?

No, only in a panic. Somehow knowing that it's around helps, knowing that you won't just go blank. It's not the fact that you're going to mess up words, because even with a prompter, if you find yourself reading a prompter then you sing like an idiot.

Because you're concentrating on ...

Yeah, you're concentrating on that, and it doesn't matter. But even with a prompter you mess up words, because you can't really read while you're playing. But it's kind of a security net, in case you have one of those terrible moments where you just black out, and you can't remember anything. That's happened to me once - at least once in my career that I remember, and it was a terrible moment, because it happened at the opening of "Closer to the Heart", of all the ... and there's nobody else playing, nowhere to run and hide! (laughs) And the crowd was singing and trying to help me get back into the flow of things.

So what, did you just step back from the mic and point at the crowd?

I just stepped back to the mic, went blank, and they were kind of smiling at me and I just joined in and went, "Yeah, okay, now I got it."

Okay, and they thought you were stepping back to listen to their singing ...

Yeah, that's right. (laughs) They're always the first ones to point out when you make a mistake. Our fans, they know every inch of the music, so if you play something wrong, they give you a look. (laughs)

Tell them you're just jamming.

So they're creatures of structure too. They don't like us to improvise, because to them, in their minds maybe it's a mistake.

So what ... ah, I just drew a blank there.

You see, it happens to everybody. (laughs)

Next issue, CM chats with Geddy about playing with a drummer - what to listen to, how to lock into a groove, etc. He also shares some of his influences ... stay tuned.

Working With a Drummer...How To Sound Your Best

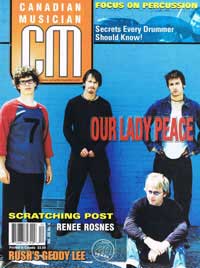

Canadian Musician Vol. XXI No.6 Nov/Dec 1999

CM picks up where we left off last issue, with part II of our Geddy Lee, bassist for Rush, interview.

Canadian Musician: So with working with a drummer, in terms of groove, with writing parts, how do you do that? Does Neil [Peart] give you parts, or do you give him a part and you just match the groove, do you guys jam? Explain your process...

Geddy Lee: Well, it used to be in the old days, before we got sophisticated, that we would just sit in a room together and we would work out the parts - we would kind of push each other. He would have an idea, or I would have an idea, and we would try to make that suit whatever the direction of the song was going. Sometimes we'd even write a song on - like a song like "YYZ", for example - Neil and I wrote that completely on bass and drums in a rehearsal environment. We just sat down together - I think maybe Alex was on the phone or something - and we just started grooving on that riff, and we ended up just putting the whole thing together. So in the old days, that was very common, and it was very direct and immediate communication. But as we got more sophisticated, the process got stupider, in a way, because Alex and I would write a song, and Neil would be working on lyrics, so he would have no rhythmic input in the early stages of the song. So we would do what we would call a demo, you know, or like a 16-track guide of the song. We'd use a drum machine or something just to keep a rudimentary rhythm. Then Neil would listen to the song, and if he loved it, then we would copy that song onto a tape for him, minus the electronic drums. The song would just have the click track so he could know the metre of the song. I would have a bass part already on there, but it would be very fundamental. Neil would then put his parts together and work them out, and we would have a little discussion on that back and forth. When he had a part that he was pleased with, I would then sit in and I would redo my bass part to see how much of my bass part needed to accommodate whatever new drums had happened. So part of what he would construct, he would construct from the bass part that existed. Part of it would he just a rhythmic arrangement that he felt suited the song best. Then we would try to get in synch, and I would redevelop the bass pattern to suit the new rhythm pattern that is on the song. Sometimes that means readjusting guitar patterns too, to accommodate a new rhythmic attitude.

What do you listen to the most when Neil's playing to keep the rhythm section going?

Bass drum. Neil and I have always had a lot of fun trying to lock in on bass drum in the early days. Even when we jam, we try to read each other's minds. Often before a sound check, we'll spend some time jamming. It's amazing, after all the years we've played together, that we can kind of sense when each other is going to go into a fill or, you know, there's just this kind of kinetic communication that we have.

How do you find the right time to switch solos when live? Do you just feel it, you just know?

Well, if you're jamming, if you're improvising, it's just a feel thing. But of course, we're creatures of structure, and we work everything out - almost everything out - beforehand. We do allow a couple of moments in the show where we just kind of go off a little bit, but it's very hard for us to break away from our structural habits. I've noticed that even the parts of our live show that we leave open for improv, by the end of the tour they're not improv anymore. We've kind of subconsciously turned them into structured parts, and they turn into orchestration as opposed to improv. It's just our nature to do that, so, you can't fight your nature.

So do you, like, soloing and that live, that's all basically written out or do you cut loose a little?

Well, we cut loose, like I say, we start off as an improv thing, with solos, but by the end of the tour they've grown into parts. It's just our ridiculous nature.

Playing live, since that's when you do the vocals and bass together the most, what's going through your mind? So you said, the bass part is completely...

[Transcriber's Note: Geddy's reply is missing from the interview, i.e. it was not printed in the magazine, and the above question was immediately followed by the next question.]

For a young bass player who's just picking up the instrument, what's the best advice could you share? What are the most important things?

For me, it's finding bass players that just blow you away, and imitating them, mimicking them, and playing around with what they do. You just take a phrase, or something that you think is impossible to play by a bass player that you love, and keep playing it until it's not impossible, and that makes you realize the potential that you have. Really, most bass players - most musicians, I think, start out like that. They've got that fire in their belly and want to play as well as the guy that they're listening to. There's no better way than starting on that road of imitating them. Eventually you'll realize that even though I can play this part this guy plays, it doesn't quite sound the same, because your fingering is different, because every human being's fingers are different, and that's the first inkling that you have of what a musician's style really is. The sound that a musician makes is uniquely his own and comes from his fingers - it's the way he holds the guitar, it's the way he bends the strings, it's his choice of notes, his thought patterns. It's a nice technical exercise to copy a guy that you love.

But writing something that good is the big step.

Yeah. Well, that comes in time, and that comes with confidence and experimentation, but even me playing a part by Jack Bruce didn't really sound like Jack Bruce because Jack Bruce is the only guy that can sound that way, because his sound comes from his hands. I really believe that that's true, and I think with most musicians, it just takes them a while to find themselves and to totally identify and develop their own style of play.

Who did you used to imitate?

Well, I imitated Jack Bruce, I imitated John Entwhistle, I imitated Jack Cassidy from the Jefferson Airplane who was a great unheralded bass player. Later on I imitated Chris Squire, I imitated Jeff Berlin, you know, people like that.

You keep mentioning Jack Bruce. Was he the standout player for you?

When I first started, absolutely. He was the man.

Any modern players? Or maybe I shouldn't say modern, but any newer players that you've heard that have caught your attention?

Les Claypool is a very unique player, plays great. The bass player of Curve, he's a really interesting melodic player. I like what he writes. I think what you find as a bass player, when you first start, it's all about chops, and how well or how fast a guy can play. As I got older, I was more interested in the melodies that bass players wrote and how they enhanced the music. So that's two aspects that I would encourage a young bass player to study, not only bass as a rifting instrument, but bass as kind of a subsonic melodic instrument that can contribute really quite a lot of mood. Your choice of notes affects the mood dramatically, so you can have these melodies that are just kind of weaving under the surface of a song, and they can make a tremendous difference. Paul McCartney was, in my mind, never a great player, but he wrote great parts for the context of the music that he played. My ears have always been drawn to that. The old Motown guys wrote wonderful melodic and infectious melodies too that you couldn't get out of your head - "My Girl" and those old Motown classics. They're great bass patterns and they have in some ways become almost the most integral part of why people remember the songs. I think it's important to be inspired to play well, to play fast, to learn your chops, but the more melody you study, the more your taste improves, and the more you can take your skills and apply them in the different contexts of the different styles of music.

What would be a good exercise for somebody to try, something good for chops? Do you have any favourite exercises that helped you develop a certain style or a certain way of playing?

Not really any one particular exercise. Like I say, in the early days I would just take a lick by a bass player I admired and play it to death, and then as I got older I would write a part. I would write a part that was really complicated and really used a different part of the neck. For example, I would listen to something that Jeff Berlin would play, and it would be very obviously jazz-influenced, but it was also modal. When you learn by playing only rock or blues, you stay in a particular mode. When you start listening to other guys, some of the jazz guys, they slide from one mode into another, and suddenly the character or the flavour of the bass part is changed. When you twig on that, it opens up a whole other level of play for you. Suddenly you're able to take your rock chops and slide out of them into a whole different flavour. That comes in time. So I would do that. I would listen to a guy that was in a different style than me, and I would try to learn from him, in terms of where he would take the melody, and then I would apply it to my rock context, and it would sound fresher or more unusual.