"New World Man" - "We Have Assumed Control" - "Rush's Career in 10 Albums"

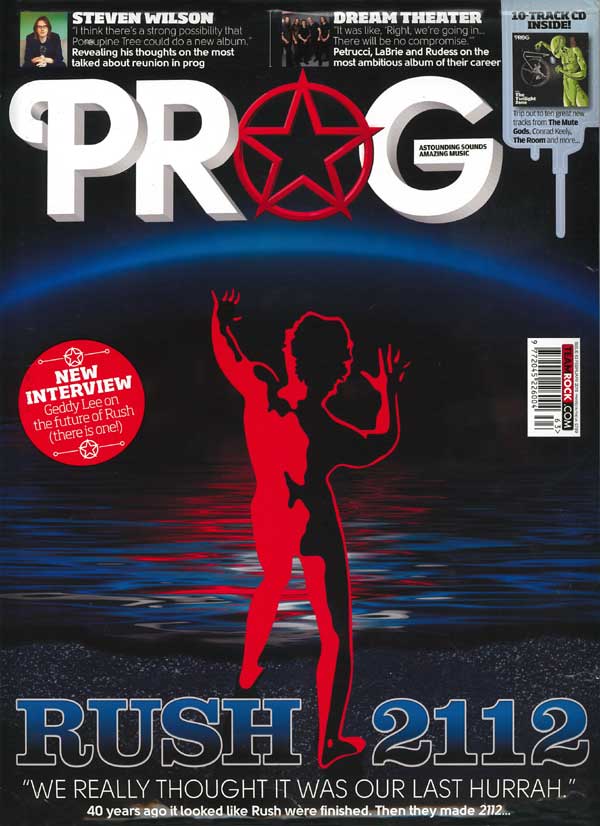

Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, and Neil Peart talks us through the creation of 2112, the album that turned Rush into prog superstars - but which could have destroyed the band...

By Philip Wilding, Dave Everley, Geddy Lee, PROG, February 2016, transcribed by John Patuto

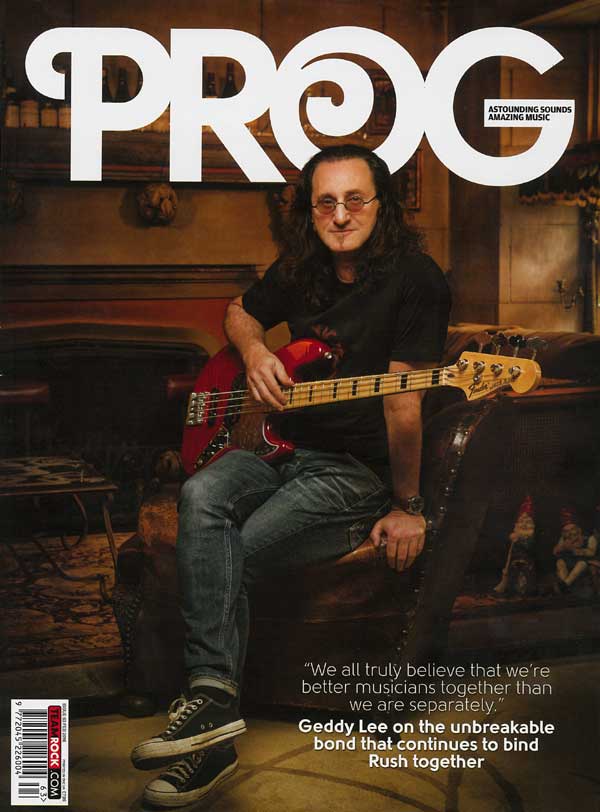

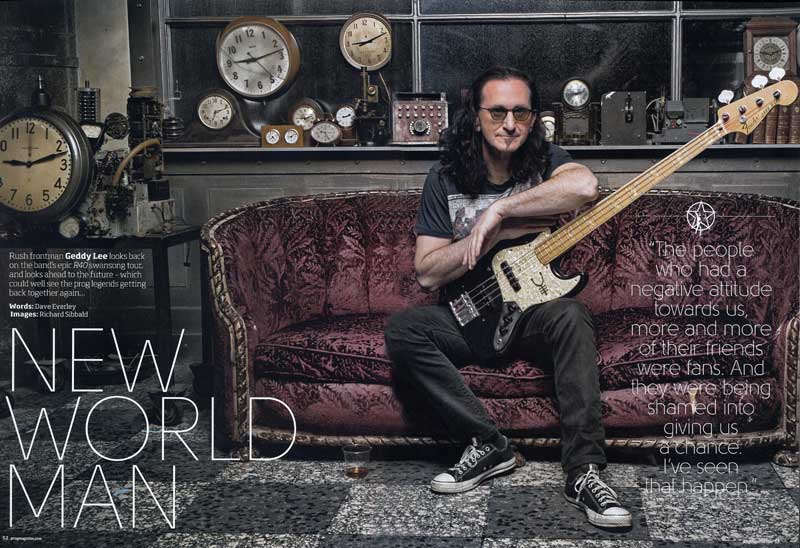

New World Man

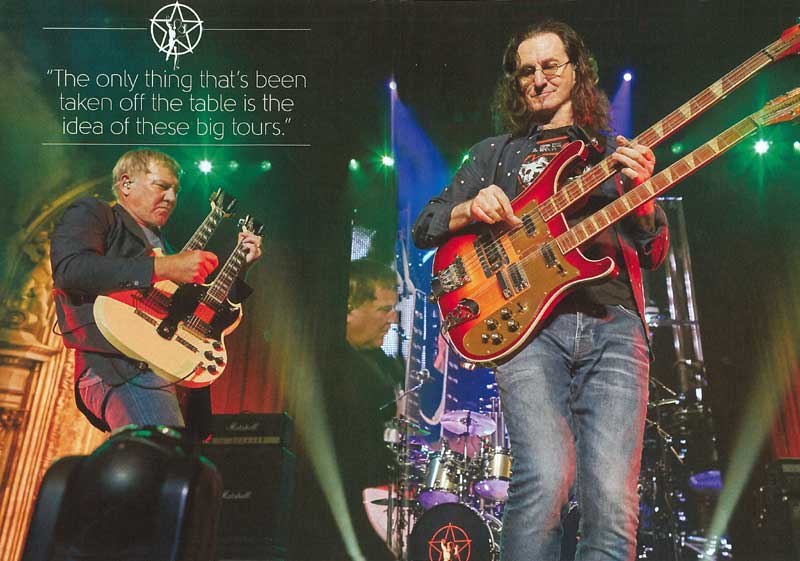

Rush frontman Geddy Lee looks back on the band's epic R40 swansong tour, and looks ahead to the future - which could well see the prog legends getting back together again...

Geddy Lee is the very model of cultured Canadian gentility. Sipping an early evening Bloody Mary in the bar of one of West London's more tasteful upmarket hotels, Rush's singer and bassist is winding his way through a series of diverse topics, including the British capital's theatre scene ("It's the most vibrant in the world"), his wine collection ("How much is it worth? I try not to think about that") and his admiration for such disparate mavericks as Bjork, comedian Eddie Izzard and recently inducted Canadian President Justin Trudeau.

"I just admire anyone who refuses to conform to the norm," he says, inadvertently sounding like one of his own band's lyrics. But there's pressing business at hand. It's four months since Rush finished their R40 tour, a typically contrary celebration of what was actually the 41st anniversary of their debut album. To the despair of their legion of fans, R40 was pitched as the band's swansong tour, the strains of four decades of life on the road having taken their toll on guitarist Alex Lifeson, who has been diagnosed with arthritis in his hand, and Neil Peart, who cited the sheer effort of getting match fit for the band's typically epic jaunts as his reason for bowing out of the live circus.

Lee is ostensibly here to promote the R40 Live DVD and CD set, but as he peers over his dark, round sunglasses, he knows that people want to hear just one thing: that Rush aren't over. And over the course of an hour, it becomes blindingly apparent that he doesn't want the band he's fronted for more than 40 years to be over, either.

When you watch the R40 Live film now, what emotions does it stir?

How was the tour for you personally, in terms of what was going through your head when you were out on the road? Were you up there onstage enjoying every moment, or were you thinking, "This could be the last time"; with a lump in your throat?

In some of the interviews you did earlier this year, before the tour, it seemed like you were in denial that this would be the end of the road for Rush. Is that fair to say?

It's funny you say that, because Alex seemed pretty certain before the R40 tour that he was done with life in a touring band as well.

From the outside, Rush tours look like quite joyous affairs - the films you project onstage, the sense of camaraderie between the three of you. Is that the way they feel when you're in the middle of it?

It's ironic that it could all be coming to an end at the exact point Rush gain the sort of mainstream acceptance you never had for most of your career - making it onto the cover of Rolling Stone magazine and getting namechecks from the likes of Dave Grohl and Jack Black.

Did you notice a point when you stopped being criticised simply for being Rush?

What happened? Did you change or did the critics change?

Also, I think peer pressure played a part to a certain degree. The people who had a negative attitude towards us, more and more of their friends were fans. And they were being shamed into giving us a chance. I've seen that happen. You'd get people reluctantly saying: "[Grudging voice] Well, I didn't really like you guys, but then my friend made me come to the show and it was a good show." That started happening more and more and more.

How does that feel? Given the flak you got for large parts of your career, does it make you feel like you're doing something wrong when people like it?

After all this time, do you feel any kind of vindication at finally receiving this acceptance?

Let's hold on to the idea that Rush aren't splitting up. How have you kept the same line-up for 41 years?

I think that has a lot to do with it. And there's a musical respect for each other that's a huge part of the occasion. We all truly believe that we're better musicians together than we are separately.

Do you write songs away from Alex and Neil?

Why is that?

Given the current circumstances with the band, you've presumably at least thought about making another solo album?

Even if there isn't another Rush tour ever again, what are the chances of there being a new Rush album?

It was five years between Vapor Trails and Snakes & Arrows. It was five years between Snakes & Arrows and Clockwork Angels. By that reckoning, we're due another Rush album in 2017. How likely is that?

If you had to rate that chance as a percentage, what would it be?

How do you get Neil on board with a new album? How does that conversation go? Is it just a case of saying to him: "Get your arse down here!"?

So what would it take to get the three of you in the studio together?

Have you had that conversation with him separately? Have you broached the subject of a new Rush album?

But you're saying that you and Alex could do an album together, not as Rush?

Are you considering it?

And what would it sound like?

Does it feel like you're in limbo at the moment?

You say you're trying to be optimistic. Is it easy or hard to be optimistic right now?

So do we talk about Rush in the past tense or the present tense?

We Have Assumed Control

Lee, Lifeson and Peart talk about 2112, as the classic album turns 40.

"I think it's fair to say we didn't I feel defiant doing it. We just figured it was going to be our last hurrah, the one last time Rush got to make an album." Geddy Lee is sitting in the Milestone Hotel overlooking the swish Kensington Court in West London. He's here to talk about the band's latest, and possibly last, concert DVD, Rush: R40 Live, amid rumours of his band's demise and on the day when drummer Neil Peart appears to have dropped a bombshell via an essay for Drumhead magazine that suggests he's finally retired from the band.

Lee's been batting away break-up rumours all afternoon when Prog sits down with him to talk about a time within Rush when it wasn't their fans or the media who thought they were calling it day, but the band themselves - though not by choice.

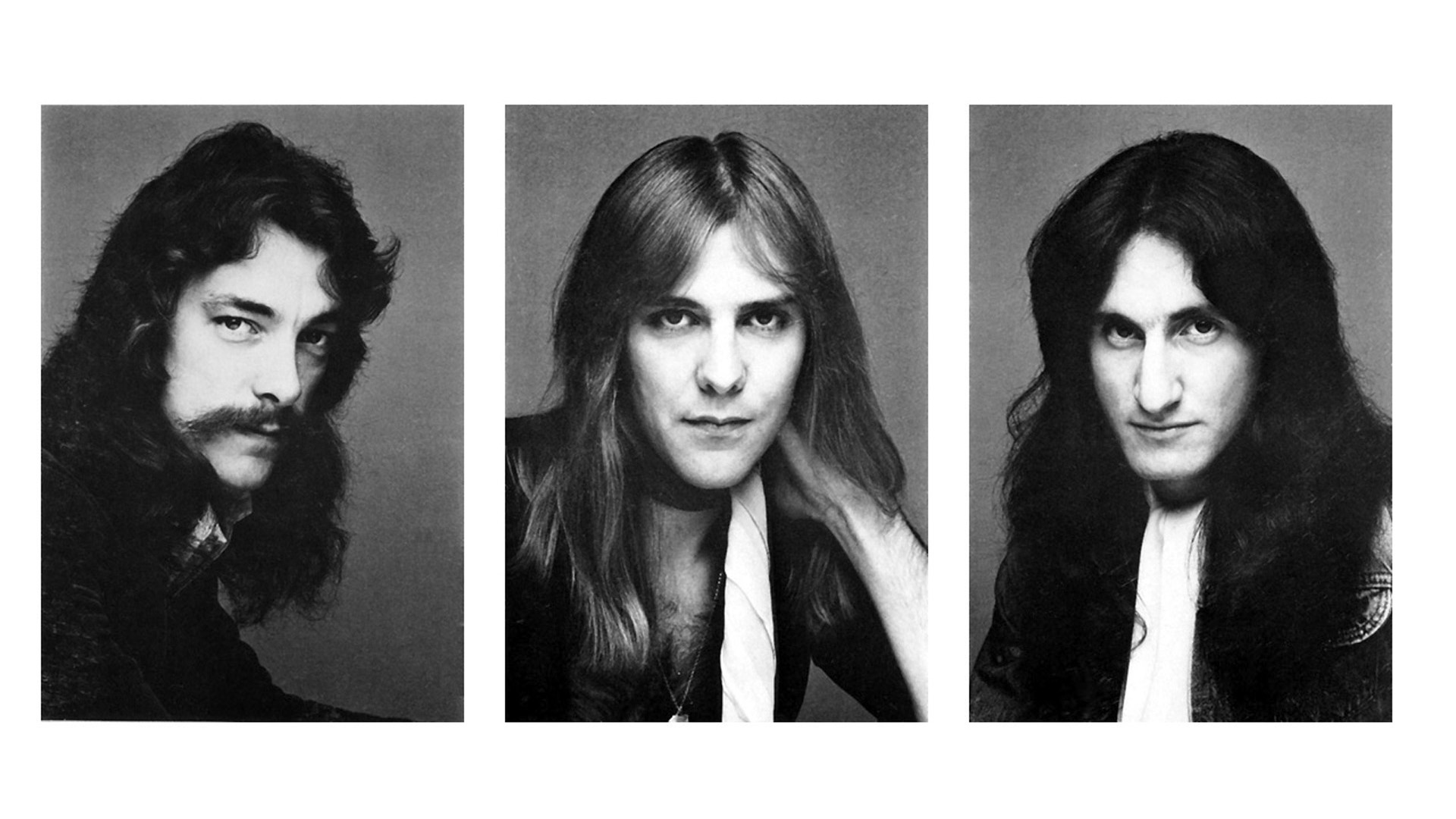

Between March 1974 and April 1976, Rush had released four studio albums and in doing so had careered between bluesy bar band and theatre headliners, at least in some parts of Canada and the US. Gene Simmons and Kiss had taken Rush under their wing, and they'd lost one drummer only to gain another who, as Geddy remembers, "knew a lot of fancy words". And in 1975's Fly By Night, they had not only created a Juno Award-winning, platinum-selling record, but also found themselves in the elevated position of the next Canadian band 'most likely to...'

But Rush, not least Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson, were becoming constrained by the more pointed - some might say inhibited - writing that populated their debut and were keen to push the creative envelope with the weighty, atmospheric battle of the underworld also known as By-Tor & The Snow Dog. In retrospect, it was Rush's creative tipping point. In not much more than a year, they'd gone from writing a blue-collar anthem like Working Man to crafting a trippy tale of Hades to close out side one of their second album.

Then again, given that it was a teenage Lee and Lifeson who had camped out overnight to see Yes play live at Massey Hall in Toronto some years before, no one can have been that surprised when they started trying to emulate some of their prog heroes.

Caress Of Steel, recorded in either two or three weeks - Lee and Lifeson can't seem to agree on this - was released in September 1975. Fly By Night had appeared in stores in February of the same year, and while Caress... was clearly an extension of the work they'd begun to do on Fly By Night, it was met by a critical response akin to angry villagers spotting Frankenstein's monster on a nearby hill, rather than with a considered critique of their music. It went gold in Canada, compared to Fly By Night's platinum status, but it alienated not only their audience but their record label too. Side one ended with the florid, 12-minute The Necromancer, while all of side two was given over to the conceptual The Fountain Of Lamneth.

"We'd seen a list of the label's financial estimates and predictions for the following year," says Lee, "and we weren't even on it." The band were so broke they were unable to pay their crew, audiences thinned and Rush dubbed the subsequent live dates as the 'Down The Tubes' tour. Their label were haranguing them for snappier and more radio-friendly material akin to some of the songs they'd recorded for Fly By Night. "But if we were going to go down in flames," says Lee, "then they were going to be our flames."

Retrospectively, it's now easy to see how the experimentation highlighted on the band's second and third albums helped create Rush's defining record (well, their defining record until Moving Pictures came along).

"We'd never have made 2112 unless we'd made Caress Of Steel," Neil Peart told Prog over lunch in Laurel Canyon as the band were mixing down their last studio album (and one that embraced their conceptual bent with glee), 2012's Clockwork Angels. "You only have to listen to that and then go listen to 2112 to see what we were trying to do and then how we did it - that seems so obvious to me."

Less so to their label, who were anything but thrilled to find that the band had opted for another side-long conceptual piece inspired by author Ayn Rand (who had also been the spark for the song Anthem that opened Fly By Night). It followed the travails of a young hero cast adrift in a futuristic dystopian society ruled by a hierarchy of priests. Music is banned, but he finds a lost guitar that ultimately leads to civilisation's emancipation, and his own death. Imagine pitching that idea to a record company executive who was hoping for Making Memories part two.

Listening to 2112's bombast now, it's easy to forget that it was mostly written on two acoustic guitars, usually in a hotel room or on the road between shows.

"Yeah, that was pretty much how we wrote it," says Lee. "It's a handy thing, the acoustic guitar - you didn't need an amp, you could do it in our Holiday Inn room, you could write in the back of the station wagon we were travelling around in. As long as you're strumming the acoustic hard, it sounds heavy, so if you write the part on it, you can imagine what it's going to sound like through electric guitars and amps. So, it's not a big stretch really to write that way. We went back and wrote [2007's] Snakes & Arrows that way too.

"The strange thing with 2112, it just kind of flowed; one song came out of the other. I remember that Alex and I had some very definite ideas of the kind of music we wanted to write, even before we saw the lyrics, the overblown intro, the pacing, the movements that were involved. And then Neil had written these lyrics and it was almost magical how well they worked. We didn't really change any of them - they just inspired us to put the music together even more. It just started to happen."

The cards fell kindly for Rush on 2112. Long-time artistic director Hugh Syme created the now famous Starman logo (as well as contributing keyboard and mellotron parts to the album) with the simplest of briefs from drummer Neil Peart.

"The evolution of the star and the man was my first true collaboration with Neil," Syme says now. "He simply described the Red Star Of The Solar Federation as being all that is contrary to free thought and creativity, and the man as our hero. I simply combined the two. Never was this intended to be the band's brand or logo, with such a strong and enduring association with all things Rush."

A few years later, Alex Lifeson shared his thoughts on why he thought the Starman logo had endured so well, and what the secret to its longevity and association with Rush might have been. "The naked bum and the fist, I think," he said without blinking. "That's it, the bum and the fist."

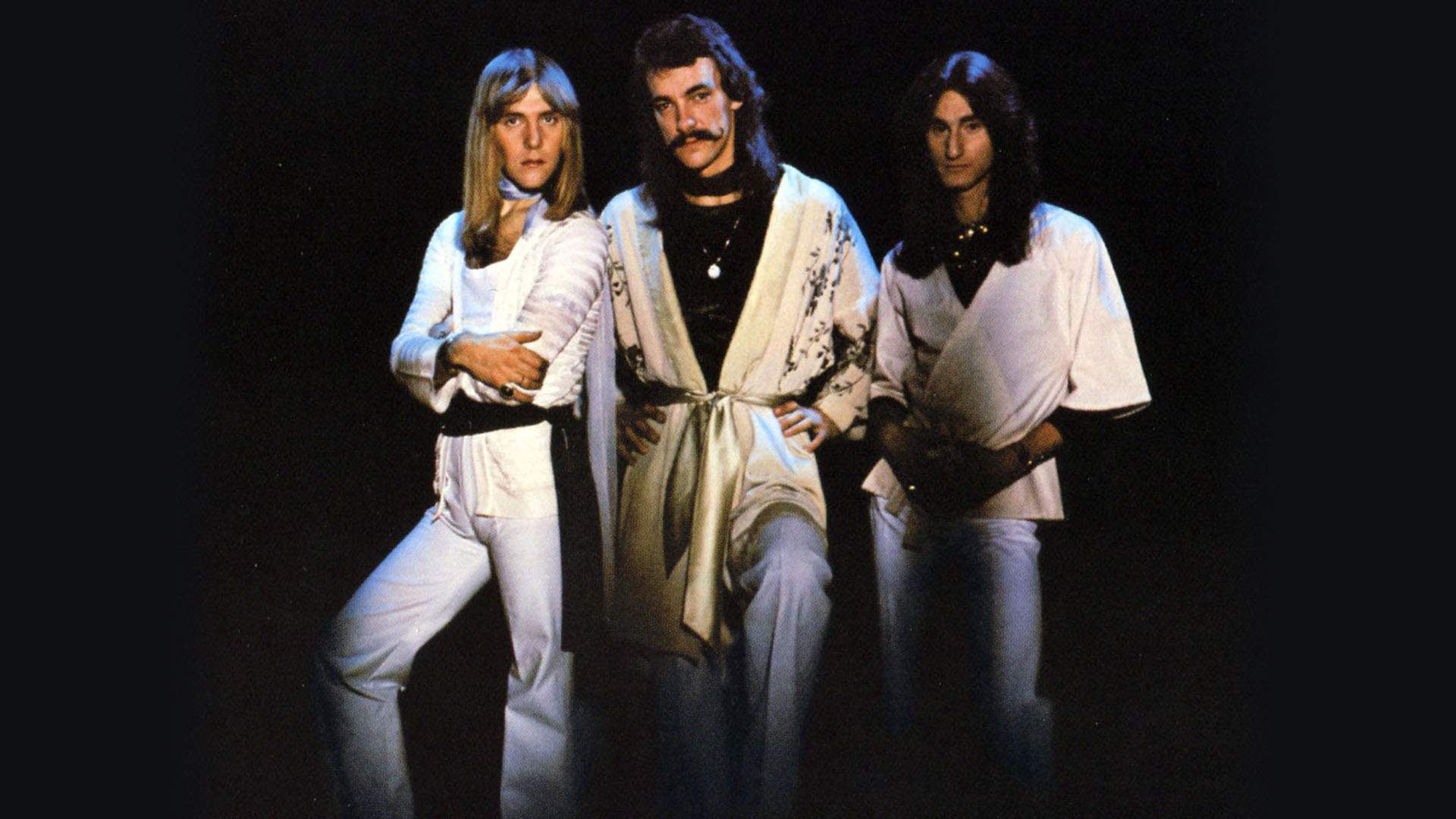

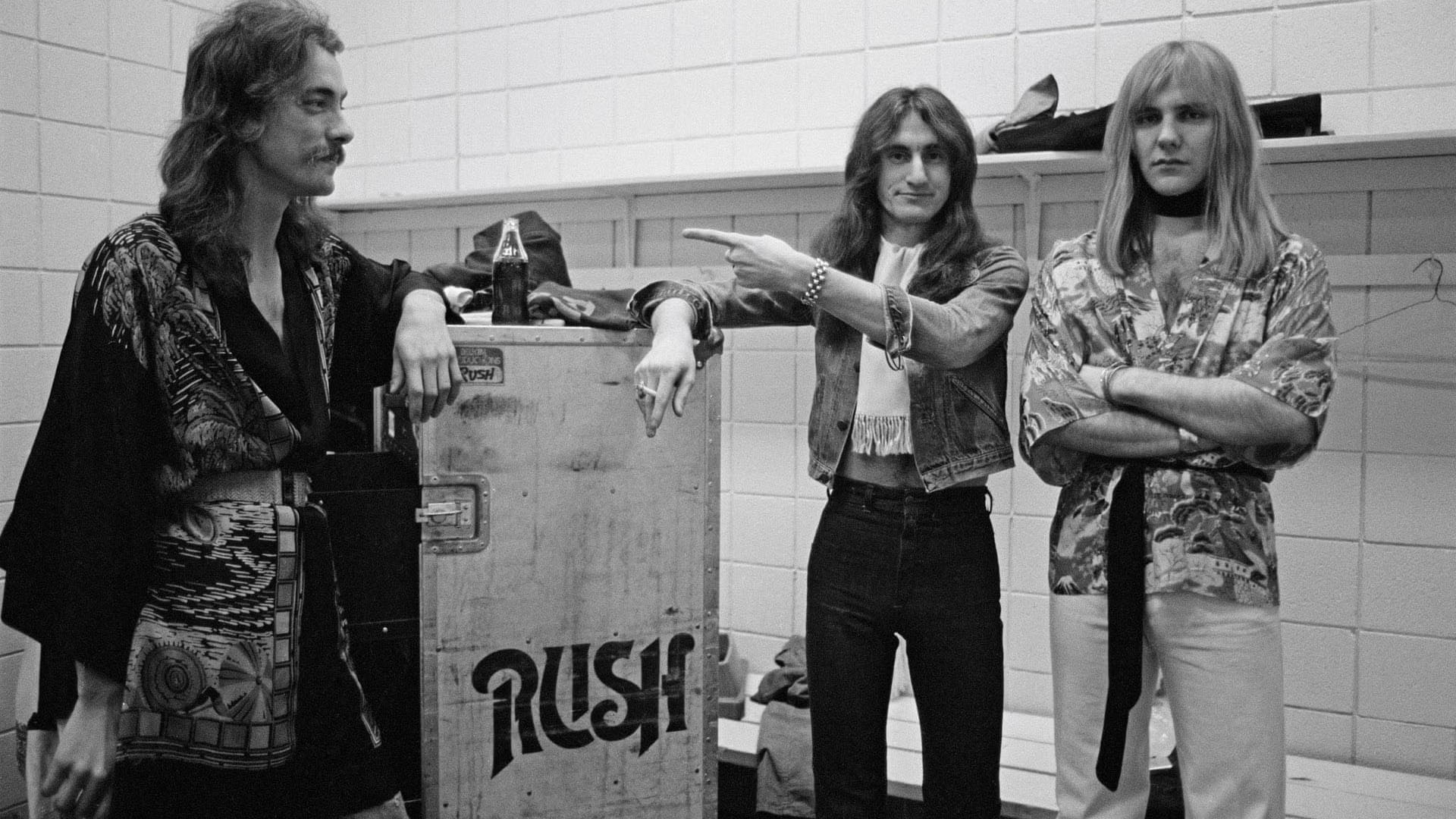

And while the cover and inner artwork were heavy on symbolism, the back sleeve was given over to a rather po-faced Rush dressed in what could only be described as kimonos.

"Ah, the kimonos, that's what they were," says Lee with a laugh. "Didn't you think they were swish?

"You know, people and our management kept saying to us, 'You need a new image.' And it's true - we weren't very image-orientated. So I remember we were in San Francisco and we're staying at the Miyako Hotel, which is in the Japanese part of town, and we said, 'Okay, let's go buy some stage clothes and get an image happening.' We just walked around the Chinese area and we found these kinds of colourful robes and said, 'Okay, let's try this,' and that's what we did. I mean, some people liked it..."

He regards Prog evenly over his round glasses. "But that straw fedora Al's wearing on the inside sleeve, nobody told Alex to bring that hat with him. That was all his idea."

And then he's laughing again.

The band went into Toronto Sound Studios with producer Terry Brown in February 1976 for the longest stint they'd ever spent on an album up until then - a remarkably scant four weeks. Lee says, "It was almost four weeks that we had, as I recall, but that felt pretty expansive to us considering how we'd worked up to that point."

Even though they had to capture the grandiosity of side one's epic story, they also took the time to create a handful of staples that were peppered across the second side of the album, some of which would stay in their live set for years to come, such as Something For Nothing and A Passage To Bangkok. And for a band that spent their working lives on the road, a bonus was that they got to go home each night.

"I know it might sound like it when you listen back to it now, but it wasn't really difficult to record," Lee says. "It just kind of happened, that record. I don't remember it being much of a struggle at all. In fact, I remember it being a pretty positive experience all round. Permanent Waves was like that too - it was a kind of record that just happened, just flew out. Sometimes albums just come crashing out of the psyche. It's amazing, you just never know."

"The best thing about 2112's success," says Neil Peart, "is that because the label were so against it, when it did take off, they could never tell us what to do again."

"It's true," says Lee, "and I think it's also fair to say it saved our careers. But it's not even like we really had any instinctive sense that it would do any better than Caress Of Steel had done before it. We liked Caress Of Steel! Of course, every record you make you think is better than the one before, but you're easily fooled by yourself because you can't really be that objective. But I think we had a feeling it was a good record and we were proud we were going out on a good record; that if this was us saying goodbye then it was a good way to go. But we had no idea it would connect with people the way it did."

And like a bat making contact with a well-weighted baseball, connect it did. Sales may have started slowly, but it would go on to reach multi-platinum status in both Canada and the USA.

"Oh yeah, it did well, but we were still way in debt," says Lee with a grin. "But we were paying it off and 2112 was helping us pay it off. It took a while, but there was a buzz as soon as the album came out. It didn't sell a lot immediately, but it was steady and it kept building. As we toured it, it kept building and building, and over the next three years it never really slowed down."

It also paved the way for something that would become another Rush staple: the double live album. All The World's A Stage (only Rush, or perhaps Peart, would filch the title of their live album from Shakespeare's As You Like It) was released in September that year to capitalise on the band's new-found success - not that making a live album had even occurred to the band.

"We hadn't really thought about it that much at all," says Lee. "The thing is that management and the record company wanted us to exploit the success of 2112 and keep it going, and live albums were kind of the thing du jour, do you know what I mean? Like a Humble Pie live album had come out and it had done really well, and you know, Kiss were doing a live album.

"All these people started dropping live albums, so they said, 'You guys have to do a live album as well.' We hadn't really thought about it until that point, and then because we were playing three nights at Massey Hall, based on the success of 2112, we thought, 'Okay, that makes sense - let's record our homecoming,' so to speak."

2112 was an unlikely platform from which to launch a career - they wouldn't even get to play side one in its entirety until the Test For Echo tour, some 20 years after the album's release (Lee might announce on All The World's A Stage, 'We'd like to play for you side one of our latest album,' but the band would omit Discovery and Oracle: The Dream).

However, it afforded them the sort of artistic latitude most artists can only dream of, even as Rush moved away from more progressive and expansive pieces and into a more moderate approach to their songwriting (less Moog and bass pedals, more hit singles). That's until they came to something approaching full circle with the conceptual Clockwork Angels album.

Fans still want to hear the story of the Priests Of The Temples Of Syrinx, and people still place 2112 at the top of fan and critics' polls alike. Did Lee know the effect the album might have when they sent it out into the world?

"No," he says with an emphatic shake of the head. "I mean, it's hard to really know because you can't be on both sides of the thing. I've had a lot of people, you know, some really accomplished musicians come up to me many times since then and say, 'That record really reached me - there was something that was so different about it.'

"But my sense is that there was a lot of passion in that record, there was a lot of ferocity in that record and it cut through, and it had a sound that was really pretty different from anything else going on at that time. I think it just cut through. You know, cut through the static of all the music that was out there, and it reached people."

And some 40 years later, it's still reaching people.

Rush's Career in 10 Albums

By Geddy Lee

RUSH (1974)

RUSH (1974)

The debut album, and the only Rush record to feature the line-up of Alex Lifeson (guitar), Geddy Lee (bass/vocals) and John Rutsey (drums).

"We recorded the album with a producer named David Stock, but it sounded so shitty we had to redo it with Terry Brown, who became our regular producer. With the second version we added a few more songs, and one of those was Finding My Way, which ended up being one of the most important tracks on the album - a real rocker.

"And the song that really got us noticed was Working Man. There was still radio in America at that time that wasn't overly programmed, and DJs had the licence to play longer tracks. Working Man was seven minutes long, and the airplay it got led to us signing with Mercury Records. That one song had an incredible impact."

FLY BY NIGHT (1975)

FLY BY NIGHT (1975)

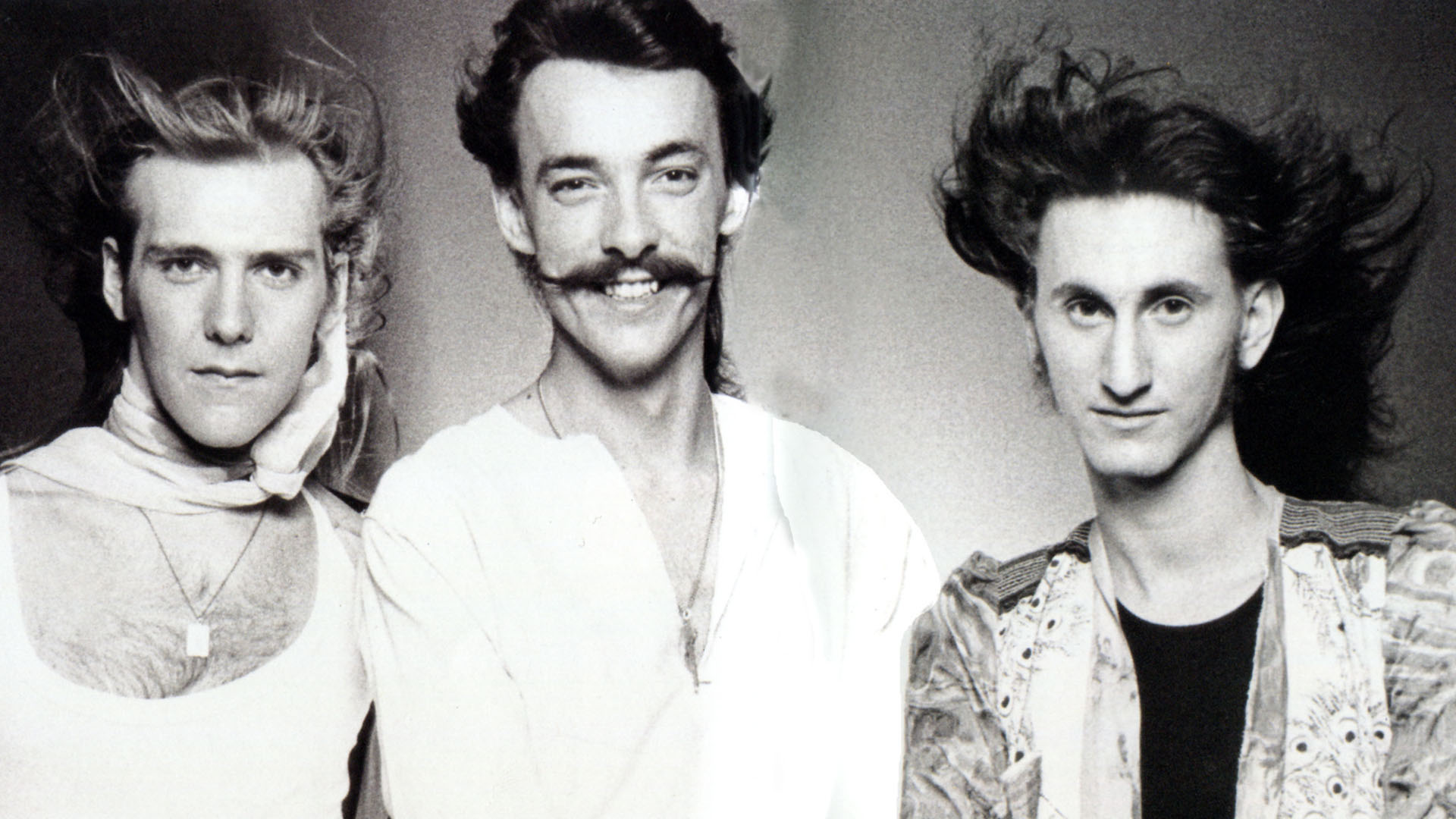

On the second album, Rutsey was out and Neil Peart was in, as drummer and lyricist. Also in for the record was a more progressive rock style.

"It wasn't Neil's idea to write lyrics. It was always Alex and I pushing him to try it because we really didn't want to do it. But it worked out pretty well for us.

"Beneath, Between & Behind was a defining moment on Fly By Night. That was one of the first lyrics Neil wrote for the band. May have been the first lyric he wrote, period. It was very wordy, really hard to sing, but Alex and I put this feverish track behind that lyric and it was great.

"By-Tor & The Snow Dog was our first real epic song. People hated that title: 'Oh my God, how pretentious!' But it was named after two dogs our manager had. It was very tongue-in-cheek. And so, in a strange way, a key Rush song began as a comedy."

2112 (1976)

2112 (1976)

The career-saving masterpiece, defined by its controversial 20-minute existentialist sci-fi title track.

"The last thing we expected was that 2112 was going to be received well because the title track was another side-long piece. But there was something about the sound of 2112 that had a much more definitive and consolidated vibe to it.

"The story in 2112 was very anti-authoritarian. It was all about freedom - creative freedom and individual freedom - so I was shocked when the NME called us neo-fascists. That's so far off the truth. It's crazy.

"But in the end, that album really saved our bacon. It brought us a lot of new fans. And side two really rounds out that record. A Passage To Bangkok, Something For Nothing, The Twilight Zone - they're just good rock songs. And that became a hallmark for us, to have that kind of diversity on every album."

A FAREWELL TO KINGS (1977)

A FAREWELL TO KINGS (1977)

Totally impervious to fashion and trends, this was a prog colossus created in the year that punk broke. Xanadu, Cygnus X-1, twittering birdsong: it's all here.

"We were so unworldly, so it was a big adventure to record in the Welsh countryside. It felt very foreign, especially the first couple of weeks, waking up with the sound of sheep baaing outside your window. But we loved recording there, going outside into the courtyard to get those ambient sounds you hear on Xanadu and A Farewell To Kings - the natural echo off the stone walls, and the birds tweeting at sunrise.

"Xanadu was one take - 11 minutes, straight through. As long as we were prepared, we could do that sort of thing. And Cygnus X-1 was a real head-first dive into outer space - a whole different kind of trip."

PERMANENT WAVES (1980)

PERMANENT WAVES (1980)

After 1978's weighty and complex Hemispheres, Rush entered a new decade with a whole new sound, complete with hit single The Spirit Of Radio.

"With Permanent Waves we wanted more immediacy in our music, just in terms of the excitement level - a different kind of energy. We still had long songs like Natural Science, which is one of my favourite songs in our entire history. But the album was really about condensing our music and trying to be better songwriters.

"The Spirit Of Radio set the tone for the whole record. It was so upbeat and so fresh. The song is about the commercialisation of music and how radio was changing. Alex's riff was supposed to represent the movement of radio waves. And the way the song jumps around, through different styles and time signatures, that was meant to sound like you were turning a dial and changing through the channels.

"The album did push us off on to a whole new period, and it felt very natural."

MOVING PICTURES (1981)

MOVING PICTURES (1981)

The biggest and best Rush album, featuring classic songs Tom Sawyer, Limelight, Red Barchetta and YYZ. But it was hard work getting it right...

"Two songs came together pretty smoothly: Limelight and Red Barchetta, which was such a great thing to play live, off the floor. Tom Sawyer was the opposite, a late bloomer. We had so much trouble getting the guitar solos down, and balancing the bottom end. But after a lot of struggling, we nailed it and it was so powerful. We were going, 'Shit, where did that come from?'

"We had such fun with Witch Hunt [part three of 'Fear']. Although it was a dark song, it involved some stupid stuff. Recording the mob shouts, the three of us went out into the studio parking lot in the freezing cold of winter. But on the night we mixed that song, we got the news that John Lennon had been shot. We were all so shocked, so sad. That's something I will never forget."

POWER WINDOWS (1985)

POWER WINDOWS (1985)

On a brilliant album, dominated by keyboards, a disgruntled guitar player took one for the team.

"I was playing keyboards, and we also brought in Andy Richards, a well-respected synth guy. So we were covering the tracks with sound, and then Alex had to sort of fight his way in. He didn't freak out - that's not his style. He's a real team guy, so he went with the flow. It was only when the record was done that he expressed his frustration.

"Of course, looking back I can totally understand it. But overall, there's a good balance between guitar songs like The Big Money and keyboard songs like Middletown Dreams, a beautiful song. And with Mystic Rhythms, the whole thing hangs around the guitar riff. Really, Alex played some great stuff on Power Windows. It's evident throughout that record."

ROLL THE BONES (1991)

ROLL THE BONES (1991)

More guitar, and great songs: the key factors in the band's finest album of the early 90s.

"It was definitely more of a guitar-oriented record. We back-pedalled a little on keyboards. They were still there, but not in that histrionic way that they're present in Presto and the previous records, Power Windows and Hold Your Fire.

"To me, in retrospect, the production on Roll The Bones lets it down a little bit. It could have sounded bigger and bolder. But I think what really makes the record is the quality of the songs. Bravado is such a well-written song. The same goes for Dreamline, and Ghost Of A Chance - I love that one.

"That whole album represents a real maturation point for us as songwriters. And the title track has really grown over time. We played it on the last tour, in 2015, and it had a different, more profound vibe. It has a deeper kind of resonance now, and I really could feel that in the way the audience reacted to it."

VAPOR TRAILS (2002)

VAPOR TRAILS (2002)

The comeback album. In 1998, following the deaths of Neil Peart's wife and daughter, he told Lee and Lifeson to consider him retired. Five years later, he and Rush returned.

"We had to rediscover how to work together, and we had to be constantly considerate of Neil's situation. His confidence had to come back slowly. We had to give him his space and at the same time, encourage him.

"The writing process was very insecure, I would say. And with regard to Neil's lyrics, it was a sensitive issue. Ghost Rider and the title track, those lyrics were very personal to Neil. We were trying to find a balance of allowing Neil to express what he'd been through, but pushing it to a more universal level so it became a valid statement about life, as opposed to just about one person's life.

"So much raw emotion went into Vapor Trails, and it was a raw-sounding record. But we got through it. That was really all that mattered."

CLOCKWORK ANGELS (2012)

CLOCKWORK ANGELS (2012)

The late-career classic. The band's 19th studio recording a proper was what every Rush fan had long dreamed of - a full-blown concept album.

"The story that Neil wrote for Clockwork Angels is wonderful. Essentially, it's a story about naïvety - a young man going out into the world, as we all do. He's duped and bamboozled, but finally he comes to the realisation that regardless of all the foolish things he's done in his life, he'd do it all again, and it was worth it.

"We didn't want the music to be a slave to the story. We wanted the songs to be seamlessly connected to each other, but also for every song to have its own life outside of the concept. That was the hardest thing. But in the end we pulled it off. It's one of the best pieces of music we've ever put together."